User's Guide of (Ḍād), a Simple Arabic Typesetting System for Mixed Latin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

End-Of-Line Hyphenation of Chemical Names (IUPAC Provisional

Pure Appl. Chem. 2020; aop IUPAC Recommendations Albert J. Dijkstra*, Karl-Heinz Hellwich, Richard M. Hartshorn, Jan Reedijk and Erik Szabó End-of-line hyphenation of chemical names (IUPAC Provisional Recommendations) https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2019-1005 Received October 16, 2019; accepted January 21, 2020 Abstract: Chemical names and in particular systematic chemical names can be so long that, when a manu- script is printed, they have to be hyphenated/divided at the end of a line. Many systematic names already contain hyphens, but sometimes not in a suitable division position. In some cases, using these hyphens as end-of-line divisions can lead to illogical divisions in print, as can also happen when hyphens are added arbi- trarily without considering the ‘chemical’ context. The present document provides recommendations and guidelines for authors of chemical manuscripts, their publishers and editors, on where to divide chemical names at the end of a line and instructions on how to avoid these names being divided at illogical places as often suggested by desk dictionaries. Instead, readability and chemical sense should prevail when authors insert optional hyphens. Accordingly, the software used to convert electronic manuscripts to print can now be programmed to avoid illogical end-of-line hyphenation and thereby save the author much time and annoy- ance when proofreading. The recommendations also allow readers of the printed article to determine which end-of-line hyphens are an integral part of the name and should not be deleted when ‘undividing’ the name. These recommendations may also prove useful in languages other than English. -

Copy Editing and Proofreading Symbols

Copy Editing and Proofreading Symbols Symbol Meaning Example Delete Remove the end fitting. Close up The tolerances are with in the range. Delete and Close up Deltete and close up the gap. not Insert The box is inserted correctly. # # Space Theprocedure is incorrect. Transpose Remove the fitting end. / or lc Lower case The Engineer and manager agreed. Capitalize A representative of nasa was present. Capitalize first letter and GARRETT PRODUCTS are great. lower case remainder stet stet Let stand Remove the battery cables. ¶ New paragraph The box is full. The meeting will be on Thursday. no ¶ Remove paragraph break The meeting will be on Thursday. no All members must attend. Move to a new position All members attended who were new. Move left Remove the faulty part. Flush left Move left. Flush right Move right. Move right Remove the faulty part. Center Table 4-1 Raise 162 Lower 162 Superscript 162 Subscript 162 . Period Rewrite the procedure. Then complete the tasks. ‘ ‘ Apostrophe or single quote The companys policies were rewritten. ; Semicolon He left however, he returned later. ; Symbol Meaning Example Colon There were three items nuts, bolts, and screws. : : , Comma Apply pressure to the first second and third bolts. , , -| Hyphen A valuable byproduct was created. sp Spell out The info was incorrect. sp Abbreviate The part was twelve feet long. || or = Align Personnel Facilities Equipment __________ Underscore The part was listed under Electrical. Run in with previous line He rewrote the pages and went home. Em dash It was the beginning so I thought. En dash The value is 120 408. -

Classifying Type Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups

Classifying Type Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups Cla sifying Type Typeface Groups The typefaces you choose can make or break a layout or design because they set the tone of the message.Choosing The the more right you font know for the about job is type, an important the better design your decision.type choices There will are be. so many different fonts available for the computer that it would be almost impossible to learn the names of every one. However, manys typefaces share similar qualities. Typographers classify fonts into groups to help Typographers classify type into groups to help remember the different kinds. Often, a font from within oneremember group can the be different substituted kinds. for Often, one nota font available from within to achieve one group the samecan be effect. substituted Different for anothertypographers usewhen different not available groupings. to achieve The classifi the samecation effect. system Different used by typographers Thunder Graphics use different includes groups. seven The major groups.classification system used byStevenson includes seven major groups. Use the Right arrow key to move to the next page. • Use the Left arrow key to move back a page. Use the key combination, Command (⌘) + Q to quit the presentation. Thunder Graphics Training • Type Workshop Typeface Groups ����������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������ -

I. In-Text Citations in Turabian-Style Papers, Superscript Numbers

MAX Center Writing References Turabian Style I. In-Text Citations In Turabian-style papers, superscript numbers (1) are placed at the end of sentences in which a source is used (quotations, paraphrasing, or any other attribution). The source of the citation is then cited in a correspondingly numbered note which provides extended information. These notes can appear as footnotes at the bottom of the page or endnotes in a list at the end of the paper. In most cases, you will also list sources at the end of the paper in a bibliography. The format for these notes is different from the format of bibliography entries. Superscript numbers should appear at the end of the cited material after all punctuation marks, except when the note refers to material before a dash, in which case the superscript should appear after it. Don’t use more than one reference number at a time if a sentence cites multiple sources—instead, use one number and include all citations in a single note. II. Foot- and Endnotes If you choose to use Endnotes instead of footnotes, they should appear on a separate page entitled Notes. Both footnotes and endnotes are formatted as follows: 1. Single Author or Editor Note Number. Author’s (or Editor’s) First and Last Names, Title of Book: Subtitle of Book (Place of Publication: Publisher’s Name, Date of Publication), XX-XX. 2. Multiple Authors Note Number. Author #1’s First and Last Names and Author #2’s First and Last Names, Title of Book: Subtitle of Book (Place of Publication: Publisher’s Name, Date of Publication), XX-XX. -

Top Ten Tips for Effective Punctuation in Legal Writing

TIPS FOR EFFECTIVE PUNCTUATION IN LEGAL WRITING* © 2005 The Writing Center at GULC. All Rights Reserved. Punctuation can be either your friend or your enemy. A typical reader will seldom notice good punctuation (though some readers do appreciate truly excellent punctuation). However, problematic punctuation will stand out to your reader and ultimately damage your credibility as a writer. The tips below are intended to help you reap the benefits of sophisticated punctuation while avoiding common pitfalls. But remember, if a sentence presents a particularly thorny punctuation problem, you may want to consider rephrasing for greater clarity. This handout addresses the following topics: THE COMMA (,)........................................................................................................................... 2 PUNCTUATING QUOTATIONS ................................................................................................. 4 THE ELLIPSIS (. .) ..................................................................................................................... 4 THE APOSTROPHE (’) ................................................................................................................ 7 THE HYPHEN (-).......................................................................................................................... 8 THE DASH (—) .......................................................................................................................... 10 THE SEMICOLON (;) ................................................................................................................ -

Revised Proposal to Encode a Punctuation Mark "Double Hyphen"

Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Revised Proposal to encode a punctuation mark "Double Hyphen" Source: German NB Status: National Body Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2011-01-17 Replaces: N3917 = L2/10-361, L2/10-162 Dashes and Hyphens A U+2E4E DOUBLE HYPHEN → 2010 hyphen → 2E17 double oblique hyphen → 003D equals sign → A78A modifier letter short equals sign · used in transcription of old German prints and handwritings · used in some non-standard punctuation · not intended for standard hyphens where the duplication is only a font variant Properties: 2E4E;DOUBLE HYPHEN;Pd;0;ON;;;;;N;;;;; Entry in LineBreak.TXT: 2E4E;BA # DOUBLE HYPHEN 1. Introduction The "ordinary" hyphen, which is representable by U+002D HYPHEN-MINUS or U+2010 HYPHEN, usually is displayed by a single short horizontal dash, but has a considerable glyph variation: it can be slanted to oblique or doubled (stacked) according to the used font. For instance, in Fraktur (Blackletter) fonts, it commonly is represented by two stacked short oblique dashes. However, in certain applications, double hyphens (consisting of two stacked short dashes) are used as characters with semantics deviating from the "ordinary" hyphen, e.g. to represent a definite unit in transliteration. For such a special application, in this case for transliteration of Coptic, U+2E17 DOUBLE OBLIQUE HYPHEN was encoded ([1], example on p. 9). However, there are other applications where the double hyphen is usually not oblique. For such applications, a "DOUBLE HYPHEN" is proposed here, which consists of two stacked short dashes which usually are horizontal. -

Typography for Scientific and Business Documents

Version 1.8 Typography for Scientific and Business Documents George Yefchak Agilent Laboratories What’s the Big Deal? This paper is about typography. But first, I digress… inch marks, so you’ll probably get to enter those manually anyway.† Nothing is perfect…) Most of us agree that the use of correct grammar — or at In American English, punctuation marks are usually placed least something approaching it — is important in our printed before closing quotes rather than after them (e.g. She said documents. Of course “printed documents” refers not just to “No!”). But don’t do this if it would confuse the message words printed on paper these days, but also to things distrib- (e.g. Did she say “no!”?). Careful placement of periods and uted by slide and overhead projection, electronic broadcast- commas is particularly important when user input to ing, the web, etc. When we write something down, we computers is described: usually make our words conform to accepted rules of For username, type “john.” Wrong grammar for a selfish reason: we want the reader to think we For username, type “john”. ok know what we’re doing! But grammar has a more fundamen- tal purpose. By following the accepted rules, we help assure For username, type john . Even better, if font usage that the reader understands our message. is explained If you don’t get into the spirit of things, you might look at Dashes typography as just another set of rules to follow. But good The three characters commonly referred to as “dashes” are: typography is important, because it serves the same two purposes as good grammar. -

Ellipsis, Hyphen, & Dash

ELLIPSIS, HYPHEN, & DASH (STYLISTIC CHOICE: ADDING DRAMATIC EFFECT) LEARNING GOALS: L.8.2: DEMONSTRATE COMMAND OF THE CONVENTIONS OF STANDARD ENGLISH CAPITALIZATION, PUNCTUATION, AND SPELLING WHEN WRITING. L.8.2.A: USE PUNCTUATION (COMMA, ELLIPSIS, DASH) TO INDICATE A PAUSE OR BREAK. ELLIPSIS INTRODUCTION VIDEO ELLIPSIS • AN ELLIPSIS IS A TYPE OF PUNCTUATION THAT IS USED TO INDICATE OMISSION OR PAUSES IN WRITING. IT IS MADE UP OF 3 DOTS … EX. NANETTE KEPT PONDERING HER DECISION . AND FINALLY DECIDED SHE HAD MADE A MISTAKE. WHEN TO USE AN ELLIPSIS 1. AN ELLIPSIS CAN BE USED WHEN QUOTING A TEXT TO OMIT (LEAVE OUT) PART OF THE TEXT. • THIS HAPPENS WHEN THE WRITER DECIDES HE/SHE ONLY NEEDS A PORTION OF A QUOTATION TO SUPPORT HIS/HER CLAIM. EXAMPLE: ORIGINAL QUOTE: "SINCE GRADUATING FROM COLLEGE IN WASHINGTON, EVA HAD BEEN TAKING MEDICINE TO RELIEVE THE PAIN OF HER RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS" (BEITO 119). WITH ELLIPSIS: "SINCE GRADUATING. EVA HAD BEEN TAKING MEDICINE TO RELIEVE THE PAIN OF HER RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS" (BEITO 119). NOTE • YOU MAY CUT OUT TEXT FROM ANYWHERE WITHIN A SENTENCE AND REPLACE IT WITH AN ELLIPSIS AS LONG AS THE REMAINING PORTIONS OF THE SENTENCE STILL MAKE SENSE AND DON’T CHANGE THE ORIGINAL MEANING OF THE SENTENCE . • (ELLIPSIS MAY BE USED AT THE BEGINNING, MIDDLE, OR END OF THE TEXT BEING QUOTED) • IF YOU HAVE AN ENTIRE PARAGRAPH, BUT ONLY WANT A FEW COMPLETE SENTENCES, YOU MAY LEAVE OUT ENTIRE SENTENCES, AS LONG AS YOU USE AN ELLIPSIS BETWEEN SENTENCES. 2. USE AN ELLIPSIS TO INDICATE WHEN A CHARACTER TRAILS OFF IN THINKING OR IN SPEAKING. -

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters

The Brill Typeface User Guide & Complete List of Characters Version 2.06, October 31, 2014 Pim Rietbroek Preamble Few typefaces – if any – allow the user to access every Latin character, every IPA character, every diacritic, and to have these combine in a typographically satisfactory manner, in a range of styles (roman, italic, and more); even fewer add full support for Greek, both modern and ancient, with specialised characters that papyrologists and epigraphers need; not to mention coverage of the Slavic languages in the Cyrillic range. The Brill typeface aims to do just that, and to be a tool for all scholars in the humanities; for Brill’s authors and editors; for Brill’s staff and service providers; and finally, for anyone in need of this tool, as long as it is not used for any commercial gain.* There are several fonts in different styles, each of which has the same set of characters as all the others. The Unicode Standard is rigorously adhered to: there is no dependence on the Private Use Area (PUA), as it happens frequently in other fonts with regard to characters carrying rare diacritics or combinations of diacritics. Instead, all alphabetic characters can carry any diacritic or combination of diacritics, even stacked, with automatic correct positioning. This is made possible by the inclusion of all of Unicode’s combining characters and by the application of extensive OpenType Glyph Positioning programming. Credits The Brill fonts are an original design by John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks. Alice Savoie contributed to Brill bold and bold italic. The black-letter (‘Fraktur’) range of characters was made by Karsten Lücke. -

Effective Punctuation

Effective Punctuation Contents: 1. Oxford commas 2. Parenthetic phrases 3. Independent clauses 4. Punctuation before or after quotation marks 5. Ellipses in quotations 6. Em dashes 7. One or two spaces after periods 8. When to capitalize after colons 1. Oxford Comma Writers disagree on whether lists of three or more should include a comma before the “and” (or “or”) and the last item in the list. Above all, consistency is key. If you do not know your reader's preference, choose one method and stick to it. Commas before the last “and” must be used when the final item in the list itself contains a conjunction (e.g., “He was charged with assault, battery, and breaking and entering.”) Option 1 Option 2 When the “Oxford Comma” is required The American flag is red, The American flag is red, You are charged with white and blue. white, and blue. trespassing, burglary, and assault and battery. 2. Parenthetic phrases Use commas to set off words and phrases that do not neatly fit into the main grammatical structure of the sentence. Nonrestrictive clauses are examples of parenthetic phrases. Unless the parenthetic phrase ends the sentence, there should always be a comma at the end of the parenthetic phrase. Do not use commas to set off phrases that, if removed, would change the meaning of the sentence, i.e., a restrictive clause. • Examples: o The Constitution, which was signed in 1787, is the supreme law of the land. o The Constitution, signed in 1787, is the supreme law of the land. o The judge, however, was not amused. -

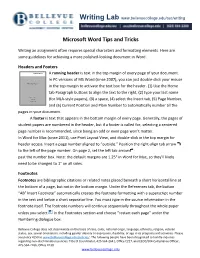

MS Word Tips and Tricks

Writing Lab www.bellevuecollege.edu/asc/writing Microsoft Word Tips and Tricks Writing an assignment often requires special characters and formatting elements. Here are some guidelines for achieving a more polished-looking document in Word. Headers and Footers A running header is text in the top margin of every page of your document. In PC versions of MS Word (since 2007), you can just double-click your mouse in the top margin to activate the text box for the header. (1) Use the Home tab Paragraph buttons to align the text to the right, (2) type your last name (for MLA-style papers), (3) a space, (4) select the Insert tab, (5) Page Number, and (6) Current Position and Plain Number to automatically number all the pages in your document. A footer is text that appears in the bottom margin of every page. Generally, the pages of student papers are numbered in the header, but if a footer is called for, selecting a centered page number is recommended, since being an odd or even page won’t matter. In Word for Mac (since 2011), use Print Layout View, and double-click in the top margin for header access. Insert a page number aligned to “outside.” Position the right-align tab arrow to the left of the page number. On page 2, set the left tab arrow past the number box. Note: the default margins are 1.25" in Word for Mac, so they’ll likely need to be changed to 1" on all sides. Footnotes Footnotes are bibliographic citations or related notes placed beneath a short horizontal line at the bottom of a page, but not in the bottom margin. -

Dialogue Has Its Own Rules for Punctuation. Commas Go in Particular Places, As Do Terminal Marks Such As Periods and Question Marks

Dialogue has its own rules for punctuation. Commas go in particular places, as do terminal marks such as periods and question marks. Only what is spoken is within the quotation marks. Other parts of the same sentence— dialogue tags and action or thought—go outside the quotation marks. Dialogue begins with a capitalized word, no matter where in the sentence it begins. (Interrupted dialogue, when it resumes, is not capped.) Only direct dialogue requires quotation marks. Direct dialogue is someone speaking. Indirect dialogue is a report that someone spoke. The word that is implied in the example of indirect dialogue. Direct: “She was a bore,” he said. Indirect: He said [that] she was a bore. Rules with examples. Single line of dialogue, no dialogue tag The entire sentence, including the period (or question mark or exclamation point) is within the quotation marks. “He loved you.” Single line with dialogue tag (attribution) following The dialogue is enclosed in quotation marks. A comma follows the dialogue and comes before the closing quotation mark. A period ends the sentence. Punctuation serves to separate the spoken words from other parts of the sentence. Because the dialogue tag—she said—is part of the same sentence, it is not capped. “He loved you,” she said. Single line with dialogue tag first The comma still separates the dialogue tag from the spoken words, but it is outside the quotation marks, and the period is inside the quotation marks. She said, “He loved you.” Single line of dialogue with dialogue tag and action The dialogue is enclosed in quotation marks.