Chalkhill – 1,000 Years of History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

London's Housing Struggles Developer&Housing Association Dec 2014

LONDON’S HOUSING STRUGGLES 2005 - 2032 47 68 30 13 55 20 56 26 62 19 61 44 43 32 10 41 1 31 2 9 17 6 67 58 53 24 8 37 46 22 64 42 63 3 48 5 69 33 54 11 52 27 59 65 12 7 35 40 34 74 51 29 38 57 50 73 66 75 14 25 18 36 21 39 15 72 4 23 71 70 49 28 60 45 16 4 - Mardyke Estate 55 - Granville Road Estate 33 - New Era Estate 31 - Love Lane Estate 41 - Bemerton Estate 4 - Larner Road 66 - South Acton Estate 26 - Alma Road Estate 7 - Tavy Bridge estate 21 - Heathside & Lethbridge 17 - Canning Town & Custom 13 - Repton Court 29 - Wood Dene Estate 24 - Cotall Street 20 - Marlowe Road Estate 6 - Leys Estate 56 - Dollis Valley Estate 37 - Woodberry Down 32 - Wards Corner 43 - Andover Estate 70 - Deans Gardens Estate 30 - Highmead Estate 11 - Abbey Road Estates House 34 - Aylesbury Estate 8 - Goresbrook Village 58 - Cricklewood Brent Cross 71 - Green Man Lane 44 - New Avenue Estate 12 - Connaught Estate 23 - Reginald Road 19 - Carpenters Estate 35 - Heygate Estate 9 - Thames View 61 - West Hendon 72 - Allen Court 47 - Ladderswood Way 14 - Maryon Road Estate 25 - Pepys Estate 36 - Elmington Estate 10 - Gascoigne Estate 62 - Grahame Park 15 - Grove Estate 28 - Kender Estate 68 - Stonegrove & Spur 73 - Havelock Estate 74 - Rectory Park 16 - Ferrier Estate Estates 75 - Leopold Estate 53 - South Kilburn 63 - Church End area 50 - Watermeadow Court 1 - Darlington Gardens 18 - Excalibur Estate 51 - West Kensingston 2 - Chippenham Gardens 38 - Myatts Fields 64 - Chalkhill Estate 45 - Tidbury Court 42 - Westbourne area & Gibbs Green Estates 3 - Briar Road Estate -

4388 the London Gazette, 25Th April 1969

4388 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25TH APRIL 1969 Budimir, Nikola ; Yugoslavia ; Plastics Machine Grima, Nicholas ; Greece ; Factory Worker; 21 Belle Operator ; 84 Boughey Road, Shelton, Stoke-on- Vue Crescent, Llandaff North, Cardiff. 17th Feb- Trent, Staffordshire. 24th February 1969. ruary 1969. Bujakowski, Henryk Stanislaw ; Poland ; Engineering Grunwald, Hermina ; Hungary ; Housewife ; 29 St. Workshop Partner ; 47 Nursery Road, Taplow, Andrews Grove, London N.I6. 6th March 1969. Buckinghamshire. 24th February 1969. Grunwald, Zoltan ; Hungary ; Meat Exporter ; 29 St. Bursy, Rudolf Antoni ; Poland ; Factory Worker ; 1 5 Andrews Grove, London N.16. 6th March 1969. Park Square, Freehold, Lancaster, Lancashire. 24th Grynowski, Konstanty ; Poland ; Welder ; 25 Leighton February 1969. Road, Uttoxeter, Staffordshire. 17th February Camacho, Jose Hilario Fernandes ; Portugal ; Com- 1969. pany Director ; Winson Close Hotel, 14 Hyde Park Guttmayer, Jozsef ; Hungary; Fitter / Assembler; 31 Gate, London S.W.7. 17th February 1969. Links Road, London N.W.2. 6th March 1969. Cernak, Jan ; Czechoslovakia ; Workshop Foreman ; Halaby, Hilda ; UA.R. ; Telephone Operator/Typist; 5 Alexandra Court, London W.9. 6th March 1969. 85 Taymount Grange, Taymount Rise, London Chmiel, Konrad Aloizy ; Poland ; Machine Tool S.E.23. 6th March 1969. Fitter ; 168 Ash Road, Saltley, Birmingham 8. 24th Hamood, Saleh Eidha; Of uncertain nationality; February 1969. Labourer; 8 Ash Grove, Wright Street, Small Chu, Wah Shek (known as Pak On Chan) ; China ; Heath, Birmingham 10. 6th March 1969. Restaurateur ; 48 Nelson Street, Liverpool. 17th Hamorak, Paulo ; Of uncertain nationality ; Packer; February 1969. 27 Fairfield Square, Wymering, Cosham, Ports- Cygal, Irena ; Poland ; Waitress ; Flat 2, 6 Kensington mouth, Hampshire. 29th January 1969. Church Court, London W.8. -

WHAT IS HEALTH REFORM? by Dr

E 514 U ti1014 NEERENCE OF SEVENTWDAY ADVENTIST5 ,, WHAT IS HEALTH REFORM? By Dr. A. H. Williams STATED in simple language, health reform as we physical exercise involved promotes the strengthen- understand it means seeking to secure and maintain ing and the maintenance in health of the mind and the best possible health of body and mind to the body. It stimulates the appetite so that simply-pre- glory of God. pared food is eaten with true relish and enjoyment. Discussing social reform such as has marked the Spend a day exercising reasonably in the open air, past two centuries, a recent writer points out that and a bread and cheese type of picnic lunch seems "in each instance of reform they began by getting "just the thing." the facts." Health reform, to be sound and sane, Many kinds of employment on which men's liveli- must similarly be based on facts. The urge toward hood depends are intrinsically unhealthy; perhaps that social reform was "derived from a quickened too sedentary; perhaps in atmospheres overheated, sense of responsibility to God;" so also must be or befouled by fumes. Modern industrial legislation the true spirit of health reform. seeks to correct these evils as much as possible; but A few years ago a would-be health reformer an- a small back garden or allotment worked with a nounced that henceforth he would restrict himself fork and spade can go far toward ensuring the to a diet of lawn grass mowings. It is true that necessary component in life of simple toil in the cows and other ruminants flourish on such a diet; open air. -

Wembley and Tokyngton, Then And

Wembley and Tokyngton Then and Now Look through this slideshow. What do you notice in the photos? • Are there any buses, cars or motorbikes? • What do the buildings look like? • Can you see any street lights? • What clothes are people wearing? • Compare the older and the newer photos of the same places. What is the same and what is different? There is a new image followed by an old image for each place. There is a location reference for each place. For example, if you would like to see where 435-441 Wembley High Road is, visit our Google map and click on the location reference WT1. The recent photos are from Google Maps, and the old photos are from our collection. Explore our collection online. These images are for personal use only as each image has its own individual copyright restrictions. Please email us for more information or visit our website. 1 Wembley and Tokyngton: list of photographs Image 1. 435-441 Wembley High Road, 2019................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Image 2. F. W. Woolworth, 435-441 Wembley High Road, 1960s. ............................................................................................................................... 5 Image 3. 513 Wembley High Road, 2019. Site of Harry Howard’s ironmongers shop. ................................................................................................. 6 Image 4. 513 Wembley High Road, 1885. Harry Howard's ironmonger shop. ............................................................................................................. -

CHALKHILL ESTATE MULTI-STOREY BLOCK MANAGEMENT Ate SECURITY

housing safe communities an evaluation of recent initiatives Edited by Steve Osborn London: Safe Neighbourhoods Unit CASE STUDY ASSESSMENT CHALKHILL ESTATE MULTI-STOREY BLOCK MANAGEMENT Ate SECURITY INITIATIVE Kendrick Estate description Chalkhill Estate is a large estate of deck access and low rise dwellings located in Wembley, directly to the south of Brent Town Hall. Construction of the estate started in 1969. and the first residents moved into the system built blocks in 1971. The estate comprises Just under 2,000 units — 1,281 in 30 medium-rise deck access blocks and 700 low-rise dwellings (houses, fiats and maisonettes). It is bordered to the north and west by main roads and to the south by a railway line. Access to the blocks is by means of a complex system of footpaths. 4 The deck access part of the estate consists of 30 concrete clad blocks of five to eight storeys linked by continuous high level access decks at every third fioor. The blocks form large courtyards, most of which are partly open on one side. The site layout is probably one of the most confusing in the country because all the blocks are more or less identical In appearance, and most of them adjoin at an angle of about 120 degrees. As a result, many people lose their sense of direction when walking through the site or along the access decks. There are estimated to be about five miles of access deck, with many interconnections, changes of direction and concealed or under-lit spaces. The layout therefore contains many of the ingredients for an environment where crime is easy to commit and residents and visitors anxieties are heightened. -

50Th Anniversary V1.0

1 September 1962 - First photograph taken by the Daily News of the new Park Lane Church, 1964 September 2012 - Fifty years on Park Lane Methodist Church sitting proudly on the hill above King Edward VII Park 2 29 September 1962 - ‘In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit I declare this building open and deliver to you the key thereof. I pray you now to dedicate it for the use of the Methodist Church in worship and service of Almighty God” Contents Spoken by Dr Majorie W. Lonsdale as she hands presiding minister Revd Maurice D Gatehouse the key to the new church Celebrating Fifty Years 2 Foreward 4 Messages 5 Park Lane Church ~ A History 6 Park Lane Church ~ A New Church Rises 8 Park Lane Ministers 1962 - 2012 10 Youth & Sunday School 14 Park Lane ~ Into the 60s, 70s, and 80s 16 Park Lane ~ Ministry & Social 18 Boys’ Brigade & Girls’ Association 20 Reflections ~ Our Stories 22 Pastoral 23 2012 – The Olympics came to London and Wembley. England’s Legendry 1966 World Cup goalkeeper Gordon Banks (left) carried the Olympic Torch through Wembley to the National Stadium two days before the start of the London 2012 Olympic Games on Events at Park Lane celebrating our 27 July Golden Jubilee in 2012 (Photo Credit: Miguel Medina/AFP) § Special Anniversary Service led by Revd Dr Mark Wakelin 2012 - Jamaica and Trinidad & Tobago both celebrated their § Black Tie Anniversary Dinner 50 years of independence since 1962. § Flower Festival on the theme of 2012 - Her Majesty the Queen Elizabeth II celebrated her ‘Momentous 2012’ Diamond Jubilee in 2012 commemorating Sixty Years on § Special Youth led services the throne 3 Foreward Cover picture: Architects drawing of the new Park Lane Methodist Church c. -

Sarah Tarlow

PALGRAVE HISTORICAL STUDIES IN THE CRIMINAL CORPSE AND ITS AFTERLIFE Series Editors: Owen Davies · Elizabeth T. Hurren Sarah Tarlow THE GOLDEN AND GHOULISH AGE OF THE GIBBET IN BRITAIN Sarah Tarlow Palgrave Historical Studies in the Criminal Corpse and its Afterlife Series Editors Owen Davies School of Humanities University of Hertfordshire Hatfeld, UK Elizabeth T. Hurren School of Historical Studies University of Leicester Leicester, UK Sarah Tarlow History and Archaeology University of Leicester Leicester, UK This limited, fnite series is based on the substantive outputs from a major, multi-disciplinary research project funded by the Wellcome Trust, investigating the meanings, treatment, and uses of the criminal corpse in Britain. It is a vehicle for methodological and substantive advances in approaches to the wider history of the body. Focussing on the period between the late seventeenth and the mid-nineteenth centuries as a cru- cial period in the formation and transformation of beliefs about the body, the series explores how the criminal body had a prominent presence in popular culture as well as science, civic life and medico-legal activity. It is historically signifcant as the site of overlapping and sometimes contradic- tory understandings between scientifc anatomy, criminal justice, popular medicine, and social geography. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14694 Sarah Tarlow The Golden and Ghoulish Age of the Gibbet in Britain Sarah Tarlow University of Leicester Leicester, UK Palgrave Historical Studies in the Criminal Corpse and its Afterlife ISBN 978-1-137-60088-2 ISBN 978-1-137-60089-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-60089-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017951552 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017. -

Document Containing

Lessons and evaluation evidence from ten Single Regeneration Budget case studies Mid term report John Rhodes, Peter Tyler, Angela Brennan, Steve Stevens, Colin Warnock and Mónica Otero-García Department of Land Economy January 2002 Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions: London This report is dedicated to the memory of John Rhodes 1941-2001. Department for Transport, Local Government and the Regions Eland House Bressenden Place London SW1E 5DU Telephone 020 7944 3000 Web site: http://www.detr.gov.uk/ © Queen’s Printer and Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 2002 This publication, excluding any logos, may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the publication specified. For any other use of this material, please write to: HMSO, The Copyright Unit, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] This is a value added publication which falls outside the scope of the HMSO Class Licence Further copies of this guide are available from: DTLR Publications Sales Centre Cambertown House Commercial Road Goldthorpe Industrial Estate Goldthorpe Rotherham S63 9BL Tel: 01709 891318 Fax: 01709 881673 ISBN 1 85112 519 1 Printed in the UK. Text printed on material containing 100% post-consumer waste. Cover printed on material -

Single Regeneration Budget (SRB) - Past Experience

Greater London (FRQRPLF'HYHORSPHQW Authority &RPPLWWHH 2FWREHU Report Number: 7 Subject: Single Regeneration Budget (SRB) - Past Experience Report of: Interim Head Of Secretariat 1. Summary This Committee agreed that a scrutiny of past SRB funding could form part of its work programme this year. As a first step, this report summarises the most recent report on past SRB experience available as well as giving the results of a literature search. 2. Background 2.1 SRB is the biggest single form of Economic Development Government Funding and has undergone a number of changes since inception in 1994. 2.2 This funding is distributed by Regional Development Agencies outside London, and through the London Development Agency under the direction of the Mayor in London. 2.3 As the main Committee with terms of reference specifically targeted at economic development (although other Committees of the Assembly could be said to have responsibilities that have economic development consequences), the Committee at its last meeting considered it appropriate to investigate the issue more thoroughly. 2.4 Another report on this agenda considers the last round of SRB funding – SRB6. This report aims to go further back and considers lessons from previous rounds. This is becoming all the more timely given the current debate over SRB funding and whether it ought to change in the near future. 3. Future Approaches to the Work 3.1 Whilst there is considerable work on past SRB funded projects, ideally reports that cover the most recent SRB rounds (4-6) and are London specific would be most helpful. Unfortunately, no single report of this nature is available (through our literature search although research may exist somewhere). -

Mandatory Houses in Multiple Occupation Register. Licenc E

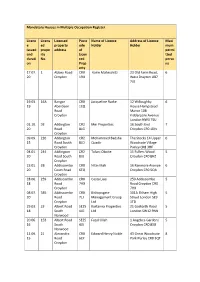

Mandatory Houses in Multiple Occupation Register. Licenc Licens Licensed Postc Name of Licence Address of Licence Maxi e ed property ode Holder Holder mum issued prope address of permi and rty Licen tted durati No. ced perso on Prop ns erty 17.07. 1 Abbey Road CR0 Karin Malleschitz 23 Old Farm Road, 6 20 Croydon 1RU West Drayton UB7 7LE 19.03. 16A Bangor CR0 Jacqueline Racke 12 Willoughby 6 19 Aberdeen 1EQ House Hampstead Road Manor 10B Croydon Kidderpore Avenue London NW3 7SU 01.10. 93 Addington CR2 Mei Properties 16 South End 7 20 Road 8LG Croydon CR0 1DN Croydon 09.09. 226 Addington CR2 Mohammed Badsha The Stocks 14 Upper 6 15 Road South 8LD Quadir Woodcote Village Croydon Purley CR8 3HF 04.01. 244 Addington CR2 Tolani Oboite 11 Fullers Wood 5 20 Road South 8LE Croydon CR0 8HZ Croydon 23.01. 2B Addiscombe CR0 Nitin Mali 16 Ranmore Avenue 6 20 Court Road 6TQ Croydon CR0 5QA Croydon 28.06. 259 Addiscombe CR0 Costa Liasi 259 Addiscombe 5 18 Road 7HX Road Croydon CR0 Croydon 7HX 08.07. 385 Addiscombe CR0 Bishopsgate 101A Eltham High 5 20 Road 7LJ Management Group Street London SE9 Croydon Ltd 1TD 29.03. 23 Albert Road SE25 Kartanna Properties 21 Gaskarth Road 5 18 South 4JD Ltd London SW12 9NN Norwood 20.06. 153 Albert Road SE25 Fazal Ullah 1 Angelica Gardens 5 16 South 4JS Croydon CR0 8XB Norwood 11.09. 21 Alexandra CR0 Edward Henry Noble 43 Great Woodcote 8 15 Road 6EY Park Purley CR8 3QT Croydon 13.02. -

Auction Catalogue October 2013

auction Catalogue october 2013 DaY 1 LONDON tuesday 22nd october at 1.00pm DaY 2 GLASGOW thursday 24th october at 1.00pm SpeCial one lot aUCtion LIVERPOOL tuesday 29th october at 6.30pm auction Calendar 2013 Regional & national Jan Feb Mar apr May Jun Jul aug Sept oct nov Dec Birmingham 15th 4th glasgow 5th 25th 11th 24th london 30th 19th 30th 6th 16th 10th 22nd 10th Manchester 14th 16th 3rd 5th nottingham 14th 4th 6th Closing Date 7th Jan 7th Jan 15th Feb 22nd Mar 15th apr 8th May 11th Jun 5th aug 23rd Sep 7th nov WeStCoUNTRY Jan Feb Mar apr May Jun Jul aug Sept oct nov Dec exeter 20th 18th 19th 12th 31st 12th Closing Date 23rd Jan 20th Mar 15th May 7th aug 2nd oct 15th nov all CorreSponDenCe: HeaD offiCe LOnDon offiCe WeStCoUntry OffiCe 80–86 new london Road, tel: 0207 963 0628 tel: 0870 241 4343 Chelmsford, essex CM2 0pD email: [email protected] email: [email protected] tel: 0870 240 1140 email: [email protected] Venues BirmingHaM Auction glaSgoW Auction lonDon auction aSton Villa FootBall Club SWalloW Hotel tHe paRk la ne Hotel trinity Road, Birmingham B6 6He 517 paisley Road West, glasgow g51 1RW piccadilly, london W1J 7BX MancheSteR auction nottingHaM auction ExeteR auction HaYDoCk paRk RaCeCourse nottingHaM RaCeCourse Sandy paRk ConFeRenCe CentRe newton-le-Willows, Merseyside Wa12 0HQ Colwick park, nottingham NG2 4Be Sandy park Way, exeter eX2 7NN auctioneer’s note on behalf of the auction team i would like to extend to you my warmest wishes and i hope i will see you at one of our forthcoming sales taking place in london and glasgow in the latter part of october. -

A Bibliography of Design Value for the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment

The Bartlett School of Planning University College London a bibliography of design value for The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment researched and written by: Matthew Carmona Sarah Carmona Wendy Clarke April 2001 The Bartlett School of Planning University College London Contents Page No 1. Introduction 3 2. Health 4 3. Education 26 4. Crime (& safety) 43 5. Housing 59 6. Social Inclusion (& regeneration) 76 2 The Bartlett School of Planning University College London 1. introduction the bibliography This bibliography of design value represents a systematic attempt to collate research that examines the ‘value added by good design in five key areas: • Health • Education • Crime (& safety) • Housing • Social inclusion (& regeneration) The bibliography provides a first attempt to bring together knowledge in these key areas of public and private sector interest. It offers a clear evidential base to back arguments that better design adds social, economic and environmental value and is therefore a worthwhile investment. No claim is made that the bibliography is comprehensive in any of the areas examined. Indeed, in some of the area (particularly crime and housing) it may merely represent the tip of the iceberg. Nevertheless, 135 sources have been brought together mainly from across the English speaking world which together start to make a strong case that better design adds value. In the main the bibliography reviews existing published sources. Some of the entries, however, represent work in progress and a few represent the outcomes of discussions the authors had with key individuals in the field. the structure The bibliography is listed alphabetically by author in its five substantive sections.