Hohokam Reservoirs, Tucson Presidio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USGS Open-File Report 2009-1269, Appendix 1

Appendix 1. Summary of location, basin, and hydrological-regime characteristics for U.S. Geological Survey streamflow-gaging stations in Arizona and parts of adjacent states that were used to calibrate hydrological-regime models [Hydrologic provinces: 1, Plateau Uplands; 2, Central Highlands; 3, Basin and Range Lowlands; e, value not present in database and was estimated for the purpose of model development] Average percent of Latitude, Longitude, Site Complete Number of Percent of year with Hydrologic decimal decimal Hydrologic altitude, Drainage area, years of perennial years no flow, Identifier Name unit code degrees degrees province feet square miles record years perennial 1950-2005 09379050 LUKACHUKAI CREEK NEAR 14080204 36.47750 109.35010 1 5,750 160e 5 1 20% 2% LUKACHUKAI, AZ 09379180 LAGUNA CREEK AT DENNEHOTSO, 14080204 36.85389 109.84595 1 4,985 414.0 9 0 0% 39% AZ 09379200 CHINLE CREEK NEAR MEXICAN 14080204 36.94389 109.71067 1 4,720 3,650.0 41 0 0% 15% WATER, AZ 09382000 PARIA RIVER AT LEES FERRY, AZ 14070007 36.87221 111.59461 1 3,124 1,410.0 56 56 100% 0% 09383200 LEE VALLEY CR AB LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.50204 1 9,440e 1.3 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383220 LEE VALLEY CREEK TRIBUTARY 15020001 33.93894 109.50204 1 9,440e 0.5 6 0 0% 49% NEAR GREER, ARIZ. 09383250 LEE VALLEY CR BL LEE VALLEY RES 15020001 33.94172 109.49787 1 9,400e 1.9 6 6 100% 0% NR GREER, AZ. 09383400 LITTLE COLORADO RIVER AT GREER, 15020001 34.01671 109.45731 1 8,283 29.1 22 22 100% 0% ARIZ. -

Historical Geomorphology .. and Hydrology of the Santa Cruz River

Historical Geomorphology .. and Hydrology of the Santa Cruz River Michelle Lee Wood, P. Kyle House, and Philip A. Pearthree Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report 99-13 July 1999 Text 98 p., 1 sheet, scale 1: 100,000 Investigations supported by the Arizona State Land Department as part of their efforts to gather technical information for a stream navigability assessment This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Arizona Geological Survey standards. EXTENDED ABSTRACT This report provides baseline information on the physical characteristics of the Santa Cruz River to be used by the Arizona Stream Navigability Commission in its determination of the potential navigability of the Santa Cruz River at the time of Statehood. The primary goals of this report are: (1) to give a descriptive overview of the geography, geology, climatology, vegetation and hydrology that define the character of the Santa Cruz River; and, (2) to describe how the character of the Santa Cruz River has changed since the time of Statehood with special focus on the streamflow conditions and geomorphic changes such as channel change and movement. This report is based on a review of the available literature and analyses of historical survey maps, aerial photographs, and U.S. Geological Survey streamgage records. The Santa Cruz River has its source at the southern base of the Canelo Hills in the Mexican Highlands portion of the Basin and Range province. The river flows south through the San Rafael Valley before crossing the international border into Mexico. It describes a loop of about 30 miles before it re-enters the United States six miles east of Nogales, and continues northward past Tucson to its confluence with the Gila River a few miles above the mouth of the Salt River. -

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1967 Part 9 .-Colorado River Basin

Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1967 Part 9 .-Colorado River Basin Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1967 Part 9 .-Colorado River Basin By H. P. Eisenhuth GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 579 Washington J 968 United States Department of the Interior STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary Geological Survey William T. Pecora, Director Free on application to the U.S. Geological Survey, Washington, D.C. 20242 Index of Surface-Water Records to September 30, 1967 Part 9 .-Colorado River Basin By H. P. Eisenhuth INTRODUCTION This report lists the streamflow and reservoir stations in the Colorado River basin for which records have been or are to bepublishedinreportsoftheGeological Survey for periods through September 30, 1967. It supersedes Geobgical Survey Circular 509. Basic data on surface-water supply have been published in an annual series of water-supply papers consisting of several volumes, including one each for the States of Alaska and Hawaii. The area of the other 48 States is divided into 14 parts whose boundaries coincide with certain natural drainage lines. Prior to 1951, the records for the 48 States were published in 14 volumes, one for each of the parts. From 1951 to 1960, the records for the 48 States were pub~.ished annually in 18 volumes, there being 2 volumes each for Parts 1, 2, 3, and 6. The boundaries of the various parts are shown on the map in figure 1. Beginning in 1961, the annual series ofwater-supplypapers on surface-water supply was changed to a 5-year S<~ries. Records for the period 1961-65 will bepublishedin a series of water-supply papers using the same 14-part division for the 48 States, but most parts will be further subdivided into two or more volumes. -

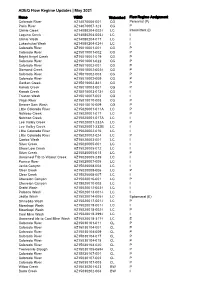

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021

ADEQ Flow Regime Updates | May 2021 Name WBID Watershed Flow Regime Assignment Colorado River AZ14070006-001 CG Perennial (P) Paria River AZ14070007-123 CG P Chinle Creek AZ14080204-002-I LC Intermittent (I) Laguna Creek AZ14080204-003-I LC I Chinle Wash AZ14080204-017 LC I Lukachukai Wash AZ14080204-024-I LC I Colorado River AZ15010001-001 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-002 CG P Bright Angel Creek AZ15010001-019 CG P Colorado River AZ15010001-022 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-001 CG P Diamond Creek AZ15010002-002-I CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-003 CG P Colorado River AZ15010002-009 CG P Garden Creek AZ15010002-841 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-001 CG P Kanab Creek AZ15010003-013-I CG I Truxton Wash AZ15010007-002 CG I Virgin River AZ15010010-003 CG P Beaver Dam Wash AZ15010010-009 CG P Little Colorado River AZ15020001-011A LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017 LC P Nutrioso Creek AZ15020001-017A LC I Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232A LC P Lee Valley Creek AZ15020001-232B LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-016 LC I Little Colorado River AZ15020002-024 LC P Carrizo Wash AZ15020003-001 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-001 LC I Show Low Creek AZ15020005-012 LC I Silver Creek AZ15020005-013 LC P Unnamed Trib to Walnut Creek AZ15020005-239 LC I Puerco River AZ15020007-005 LC I Jacks Canyon AZ15020008-004 LC I Clear Creek AZ15020008-006 LC P Clear Creek AZ15020008-007 LC I Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-001 LC P Chevelon Canyon AZ15020010-003 LC I Oraibi Wash AZ15020012-003-I LC I Polacca Wash AZ15020013-001-I LC I Jadito Wash AZ15020014-005-I LC Ephemeral -

Brawley Wash - Los Robles Wash Watershed - Arizona (Altar Wash - Brawley Wash Watershed) Released By

NEMO Watershed-Based Plan Santa Cruz Watershed Item Type text; Report Authors Uhlman, Kristine; Guertin, D. Phillip; Levick, Lainie R.; Sprouse, Terry; Westfall, Erin; Holmgren, Cassie; Fisher, Ariel Download date 27/09/2021 06:23:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/188192 Brawley Wash - Los Robles Wash Watershed - Arizona (Altar Wash - Brawley Wash Watershed) Released by: Sharon Medgal David McKay Director State Conservationist University of Arizona U.S. Department of Agriculture Water Resources Research Center Natural Resources Conservation Service Principle Investigators: Dino DeSimone - Natural Resources Conservation Service, Phoenix, Arizona Keith Larson - Natural Resources Conservation Service, Phoenix, Arizona Kristine Uhlman - Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona D. Phil Guertin - School of Natural Resources, University of Arizona Cite as: USDA Natural Resource ConservationConservations Service, Serivce, Arizona Arizona and and University University of of Arizona Arisona Water Water Resources Resources Research Center. 2008. BrawleyLittle Colorado Wash - RiverLos Robles Headwaters, Wash Watershed, Arizona, Rapid (Altar Watershed Wash - Brawley Assessment. Wash Watershed), Arizona, Rapid Watershed Assessment. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at 202-720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C., 20250-9410 or call (202) 720-5964 (voice or TDD). -

Floods of September 1970 in Arizona, Utah and Colorado

WATER-RESOURCES REPORT NUMBER FORTY - FOUR ARIZONA STATE LAND DEPARTMENT ANDREW L. BETTWY. COMMISSIONER FLOODS OF SEPTE1VIBER 1970 IN ARIZONA, UTAH, AND COLORADO BY R. H. ROESKE PREPARED BY THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PHOENIX. ARIZONA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR APRIL 1971 'Water Rights Adjudication Team Civil Division Attorney Generars Office: CONTENTS Page Introduction - - ----------------------------------------------- 1 Acknowledgments -------------------------------------------- 1 The storm ---------------------------- - - --------------------- 3 Descri¢ionof floods ----------------------------------------- 4 Southern Arizona----------------------------------------- 4 Centrru Arizona------------------------------------------ 4 Northeastern Arizona------------------------------------- 13 Southeastern Utah and southwestern Colorado --------------- 14 ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1-5. Maps showing: 1. Area of report ----------------------------- 2 2. Rainfrul, September 4- 6, 1970, in southern and central Arizona -------------------------- 5 3. Rainfall, September 5- 6, 1970, in northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado -------------------------------- 7 4. Location of sites where flood data were collected for floods of September 4-7, 1970, in Ariz ona ------------------------ - - - - - - - - - 9 5. Location of sites where flood data were collected for floods of September 5- 6, 12-14, 1970, in northeastern Arizona, southeastern Utah, and southwestern Colorado-------------------- 15 ITI IV TABLES Page TABLE 1. -

1Tuiurrmtj of Arizrnta &Xtlitin DEPARTMENT of AGRICULTURE

The Chemical Composition of Representative Arizona Waters Item Type text; Book Authors Smith, H. V.; Caster, A. B.; Fuller, W. H.; Breazale, E. L.; Draper, George Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Download date 01/10/2021 06:34:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/212507 Bulletin 225 November 1949 1tuiurrMtj of Arizrnta &xtlitin DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE THE CHEMICAL COMPOSITION OF REPRESENTATIVE ARIZONA WATERS Agricultural Experiment Station University of Arizona, Tucson ORGANIZATION Board of Regents Dan E. Garvey (ex officio) Governor of Arizona Marion L. Brooks, B.S., M.A. (ex officio) State Superintendent of Public Instruction W. R. Ellsworth, President Term Expires Jan., 1951 Samuel H. Morris, A.B., J.D Term Expires Jan., 1951 Cleon T. Knapp, LL.B Term Expires Jan., 1953 John M. Scott Term Expires Jan., 1953 Walter R. Bimson, Treasurer Term Expires Jan., 1955 Lynn M. Laney, B.S., J.D., Secretary Term Expires Jan., 1955 John G. Babbitt, B.S Term Expires Jan., 1957 Michaèl B. Hodges Term Expires Jan., 1957 James Byron McCormick, S.J.D., LLD President of the University Robert L. Nugent, Ph.D Vice -President of the University Experiment Station Staff Paul S. Burgess, Ph.D Director Ralph S. Hawkins, Ph.D Vice- Director Department of Agricultural Chemistry and Soils William T. McGeorge, M.S Agricultural Chemist Theophil F. Buehrer, Ph.D Physical Chemist Howard V. Smith, M.S Associate Agricultural Chemist Wallace H. Fuller, Ph.D Associate Biochemist George E. Draper, M.S Assistant Agricultural Chemist -

Feasibility of Diverting and Detaining Flood Water and Urban Storm Runoff, and the Enhancement of Natural Recharge

Feasibility of Diverting and Detaining Flood and Urban Storm Runoff and the Enhancement of Ground Water Recharge in the Tucson Area, Pima County, Arizona (Phase I Draft) Authors Water Resources Research Center Publisher Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Download date 09/10/2021 23:23:52 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/314310 Phase I Draft FEASIBILITY OF DIVERTING AND DETAINING FLOOD WATER AND URBAN STORM RUNOFF, AND THE ENHANCEMENT OF NATURAL RECHARGE. Water Resources Research Center College of Earth Sciences University of Arizona FEASIBILITY OF DIVERTING AND DETAINING FLOOD AND URBAN STORM RUNOFF AND THE ENHANCEMENT OF GROUND WATER RECHARGE IN THE TUCSON AREA PIMA COUNTY ARIZONA DRAFT THE WATER RESOURCES RESEARCH CENTER COLLEGE OF EARTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA TUCSON, ARIZONA 85721 MAY 1980 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Prepared for United States Army Corps of Engineers Los Angeles District Tucson Urban Study Regional Flood Control Element by The University of Arizona College of Earth Sciences Water Resources Research Center in cooperation with College of Agriculture Investigators: Professor Sol D. Resnick, Director, WRRC Dr. K. James DeCook, Hydrologist, WRRC Dr. L. G. Wilson, Hydrologist, WRRC in cooperation with: Mr. J. E. Posedly, Department of Soils, Water and Engineering, College of Agriculture Project Coordinator: Jonathon C. Goldman Contributors: Editors: John E. Stufflebean K. James DeCook Dale A. Altshul Sol D. Resnick John B. Price Jonathon C. Goldman Jonathon C. Goldman Sol D. Resnick Staff: -

Watershed Groups Or Locally Active Partners

Watershed Groups or Locally Active Partners Category (Partnership, Watershed Groups or Locally Active Partners Primary Partners Watershed Contact Person Position Email/Phone Website Tribe, Forest, etc.) Altar Valley, Brawley Wash (w/in Santa Altar Valley Conservation Alliance Watershed partnership Cruz Watershed) Mary Miller Executive Director [email protected] http://www.altarvalleyconservation.org Apache-Sitgreaves National Forests/ Watershed Forest Nancy Walls A-S Natural Resources Staff Officer [email protected] Aravaipa Watershed Conservation Alliance Watershed partnership Lower San Pedro Sandy Warner President [email protected] http://www.aravaipawatershed.org Arizona Water Sentinels Sandy Bahr Water Sentinels program contact [email protected] https://www.sierraclub.org/arizona/water-sentinels Conservation Education and Science Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Organization Debbie Colodner Director [email protected] https://www.desertmuseum.org Black Canyon Trail Association/ Black Canyon Heritage Park Organization Bob Cothern [email protected] https://blackcanyonheritagepark.org Borderlands Restoration Partnership Local partnership [watershed] Kurt Vaughn Executive Director [email protected] https://www.borderlandsrestoration.org/ Cienega Watershed Partnership Watershed partnership Cienega (w/in Santa Cruz Watershed) Tom Meixner UA faculty (water) and CWP Chair [email protected] http://www.cienega.org/ Cienega Watershed Partnership Watershed partnership Cienega (w/in -

Appendix a – Data for Sample Sites, Avra Valley Sub-Basin, 1998-2001

Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Avra Valley Sub-Basin of the Tucson Active Management Area A 1998-2001 Baseline Study By Douglas Towne Arizona Dept. of Environmental Quality Water Quality Division Surface Water Section, Monitoring Unit 1110 West Washington Street Phoenix, AZ 85007-2935 Publication Number: OFR-14-06 Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Avra Valley Sub-Basin of the Tucson Active Management Area: A 1998-2001 Baseline Study By Douglas C. Towne Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Open File Report 14-06 ADEQ Water Quality Division Surface Water Section Monitoring Unit 1110 West Washington St. Phoenix, Arizona 85007-2935 Thanks: Field Assistance: Elizabeth Boettcher, Royce Flora, Maureen Freark, Joe Harmon, Angela Lucci, and Wang Yu. Special recognition is extended to the many well owners who were kind enough to give permission to collect groundwater data on their property. Report Cover: An irrigated field of corn is almost ready for harvest in the late spring near the Town of Marana. Most irrigated agriculture in the Avra Valley sub-basin is located in this area, which is becoming a bedroom community of Tucson. Saguaro National Monument West and the Tucson Mountains are in the distance. iii ADEQ Ambient Groundwater Quality Open-File Reports (OFR) and Factsheets (FS): Harquahala Basin OFR 14-04, 62 p. FS 14-09, 5 p. Tonto Creek Basin OFR 13-04, 50 p. FS 13-04, 4 p. Upper Hassayampa Basin OFR 13-03, 52 p. FS 13-11, 3 p. Aravaipa Canyon Basin OFR 13-01, 46 p. FS 13-04, 4 p. Butler Valley Basin OFR 12-06, 44 p. -

Section VII Potential Linkage Zones SECTION VII POTENTIAL LINKAGE ZONES

2006 ARIZONA’S WILDLIFE LINKAGES ASSESSMENT 41 Section VII Potential Linkage Zones SECTION VII POTENTIAL LINKAGE ZONES Linkage 1 Linkage 2 Beaver Dam Slope – Virgin Slope Beaver Dam – Virgin Mountains Mohave Desert Ecoregion Mohave Desert Ecoregion County: Mohave (Linkage 1: Identified Species continued) County: Mohave Kit Fox Vulpes macrotis ADOT Engineering District: Flagstaff and Kingman Mohave Desert Tortoise Gopherus agassizii ADOT Engineering District: Flagstaff ADOT Maintenance: Fredonia and Kingman Mountain Lion Felis concolor ADOT Maintenance: Fredonia ADOT Natural Resources Management Section: Flagstaff Mule Deer Odocoileus hemionus ADOT Natural Resources Management Section: Flagstaff Speckled Dace Rhinichthys osculus Spotted Bat Euderma maculatum AGFD: Region II AGFD: Region II Virgin Chub Gila seminuda Virgin Spinedace Lepidomeda mollispinis mollispinis BLM: Arizona Strip District Woundfin Plagopterus argentissimus BLM: Arizona Strip District Congressional District: 2 Threats: Congressional District: 2 Highway (I 15) Council of Government: Western Arizona Council of Governments Urbanization Council of Government: Western Arizona Council of Governments FHWA Engineering: A2 and A4 Hydrology: FHWA Engineering: A2 Big Bend Wash Legislative District: 3 Coon Creek Legislative District: 3 Virgin River Biotic Communities (Vegetation Types): Biotic Communities (Vegetation Types): Mohave Desertscrub 100% Mohave Desertscrub 100% Land Ownership: Land Ownership: Bureau of Land Management 59% Bureau of Land Management 93% Private 27% Private -

Surface Flow, Sediment Transport and Water Quality Connections in the Lower Santa Cruz River, Arizona

Surface Flow, Sediment Transport and Water Quality Connections in the Lower Santa Cruz River, Arizona Thomas Meixner, Associate Professor of Hydrology and Water Resources, University of Arizona Eylon Shamir, Research Hydrologist, Hydrologic Research Center, San Diego Jennifer Duan, Assistant Professor of Civil Engineering, University of Arizona Report Prepared for U.S. EPA Region IX October 2009 1 Executive Summary The nature of hydrologic connections and their impact on water quality conditions in rivers is of ecological, hydrologic and biogeochemical importance. In this report, the nature of hydrologic connections and water quality impacts between the Upper Santa Cruz River basin, the Lower Santa Cruz River, and the Gila River are investigated. First a discussion of the important processes active in arid and semi-arid rivers is provided, emphasizing the nature of sediment and particulate transport and the opportunity for the channel network to provide an ecosystem service in the way of contaminant and nutrient removal. Following this, an analysis is conducted of the historical nature of hydrologic connections within the Lower Santa Cruz River system. The result of this analysis shows that existing infrastructure and actions of decision-making organizations recognize that the Upper and Lower Santa Cruz rivers are hydrologically connected. Next the nature of this hydrologic connection between the USGS gages at Cortaro and Laveen is analyzed through specific events, hydrologic response, and statistically. This analysis shows that large flows at Cortaro take approximately two days to propagate through the Santa Cruz River channel to Laveen. The statistical analysis shows that large flows at Cortaro lead to the largest flows observed during the period of record at Laveen and that these hydrologic connections of import occur approximately on an annual to bi-annual basis.