AN ANALYSIS of the REPUBLIC of TURKEY's PUBLIC RELATIONS PROGRAM in the UNITED STATES R the American University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Daily Egyptian, June 30, 1965

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC June 1965 Daily Egyptian 1965 6-30-1965 The aiD ly Egyptian, June 30, 1965 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_June1965 Volume 46, Issue 172 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, June 30, 1965." (Jun 1965). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1965 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in June 1965 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morris AsW to Give Active Role to Student Group The, Carbondale Student Davis~ Carbondale cam he past year underwrite the recognized. However. it is Council has asked that the student body vice presi ent d and importance of the hoped by the Carbondale Cam- proposed Commission on Stu- and temporary chairman of y to be made by this pus Student Council tbat tbe dent Rights and Responsibili- University Student Council. rJ)up (the Student Rights and forthcoming commission will ties be permitted ,an acti~e In the letter Davis noted e<>ponsibilities Com- function with the capability to rather than a passive role In that the "events which oc- Ission)." make recommendations be- University affairs. ,curred on the Carbon The letter continued: yond principle alone. in ~reas Tbe request, was made In campus With regard to T- e '.relevance of a na- where it is felt. by the com- a letter to Presldent Delyte W. ticular sentiments on tbe p " Hy oriented study on stu- mission, that such recom- Morris. -

The Olden Days

The Olden Days Preface: When my dad, Galen (Fritz), my Aunt Garnett, and my Uncle Art were in their eighties they wrote stories about growing up in the 1920s, ’30s, and World War II. The three of them, and their youngest sister Jeanne, were all born on a farm in Richland Township of Story County, Iowa between 1916 and 1927. They are all deceased. Their stories will make you appreciate the luxury life we live today. Stories by Galen (Fritz) Stratton Garnett Stratton Morris Arthur Stratton Stories by Galen (Fritz) Old Age by Fritz Stratton Time is humming And old age is coming Doc gave me new eyes and new knees So we kind of go steady and I’m on the ready But I hope there’s no more, if you please Life can be magic And sometimes tragic You never know what you should fear So I’ll just keep mowing If the John Deere keeps going Pretty soon we’ll start a New Year Then it’s back to snow blowing Sometimes it’s tough going When it’s icy you fall on your rear Lord, give me more magic Put a hold on the tragic And help me get out of bed every morn I’ll fire up the mower, also the blower Until I hear Gabriel’s horn What Did We Do For Fun by Fritz Stratton I grew up on a horse and he was a big part of my life for about 10 years. Our neighbor across the section was a horse buyer and he saw Dad one day and told him he had a 3-year old stallion that he thought might make a good saddle horse. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS FEBRUARY 1972 VOL. XVI NO. 1 PUBLISHED SIX TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 Alan Gowans, President Editor: James C. Massey, 614 S. Lee Street, Alexandria, Virginia 22314 Assistant Editors: Thomas M. Slade, 413 S. 26th Street, South Bend, Indiana 46615 and Elisabeth Walton, 765 Winter Street, N.E.Salem, Oregon 97301 SAH NOTICES James Burch, Robert DeGoff, Michael Dobrin, Joan Draper, 1973 Annual Meeting and Foreign Tour. Cambridge Univer Elliot A .P. Evans, Alfred Frankenstein, John L. Frisbee sity and London, August 15-27. A joint meeting, with III, L . Thomas Frye, David S. Gebhard, Herbert Hoover, sessions and tours, will be held with SAH-Great Britain Jr., Richard C. Peters, Don E. Stover, Fred Tamke, Robert at Cambridge, August 16-19, followed by a week of tours J. Tetlow, Margaret Wheaton, John M. Woodbridge, and (led by members of SAH-GB) and independent sightseeing Mrs. John M. Woodbridge. The expectation of fine weather in London. SAH-U.S. is required to notify the Bursars of brought approximately 400 people to the "City on the Bay" the Colleges at Cambridge by September 1972 of the total for a meeting with scholarly papers, a record nine tours, number of accommodations needed; therefore, members are and receptions hosted by the M. H. de Young Museum, urged to respond promptly to the announcen1ent of the Stanford Museum, University Art Museum-Berkeley, The entire program (including charter flight information, New Oakland Museum, and the San Francisco Chapter of the York-London-New York), which will reach you on or about A.I.A. -

Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 14 (1939-1940)

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Bowdoin Alumni Magazines Special Collections and Archives 1-1-1940 Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 14 (1939-1940) Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/alumni-magazines Recommended Citation Bowdoin College, "Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 14 (1939-1940)" (1940). Bowdoin Alumni Magazines. 14. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/alumni-magazines/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bowdoin Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOL. XIV THi: KOWIIOIN NO. 1 ,\ovi:A\iu:ir A Ml AW IIS i»x» The Bowdoin Group within the 1939 Group Totaled 14 WASSOOKEAG SCHOOL-CAMP 1940 Summer Season (15TH Year) —6- and 8-Week Terms Begin July 9 Lloyd Harvey Hatch, Director Lake Wassookeag, Dexter, Me. STAFF OF 20 TEACHERS AND COACHES FOR 45 STUDENTS The School-Camp offers a dual program blending education and recreation for boys who desire the advantages of a summer session in a camp setting. Wassookeag is fully accredited to leading schools and colleges, and it is not unusual for a student-camper to save a year in his preparatory course. PROGRAM ARRANGED FOR THE INDIVIDUAL: 1. All courses in the four-year prepara- tory curriculum. 2. Continuity-study effecting the transition from lower to upper form schools. 3. Advance school credits and college entrance credits by certification and examination. 4. Col- lege-introductory study for candidates who have completed college entrance requirements. -

The Foreign Service Journal, July 1965

Be among the first to know what’s going on in the world! Mam,* * gp| With a Zenith 9-band Trans-Oceanic® portable radio at your command, you’ll tune the listening posts of the world for tomorrow’s headlines — for news direct from presi¬ dential press conferences, for stock-market reports, for late up-to-the-minute accounts of the most recent space probes, and for the newest developments in the international situation. Get a Trans-Oceanic and you’ll be, in effect, among the first to know what’s go¬ ing on in the world! That’s why the Trans- Oceanic’s list of owners reads like an International “Who’s Who.” Its coverage is so broad, its station selec¬ tion so precise, its perfor¬ mance so dependable it’s the inevitable companion of statesmen, world-travelers, explorers, businessmen, and diplomats. The Trans-Oceanic tunes medium wave, long wave, and short wave from 2 to 9 MC...plus the popular 31, 25, 19, and 16 meter inter¬ national bands on band- spread ... even local FM’s fine music. And it is so light, so compact, so distinctively styled you’ll take it every¬ where you go—proudly. Write now for all the details on the Zenith Trans¬ oceanic so you can join its world-wide audience of well-informed listeners soon! TENITH The Quality Coes In Before The Name Goes On 1 Zenith Radio Corporation, Chicago, 60639 U.S.A. jfr 8BI The Royalty of television, stereophonic high fidelity instruments, phonographs, radios and hearing aids. 47 years of leadership in radionics exclusively! FOREIGN SERVICE JOURNAL PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION AMERICAN FOREIGN SERVICE ASSOCIATION The Foreign Service JOURNAL is the professional journal of the American Foreign Service and is published by the American Foreign Service Association, SAMUEL D. -

Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 17 (1942-1943)

Bowdoin College Bowdoin Digital Commons Bowdoin Alumni Magazines Special Collections and Archives 1-1-1943 Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 17 (1942-1943) Bowdoin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/alumni-magazines Recommended Citation Bowdoin College, "Bowdoin Alumnus Volume 17 (1942-1943)" (1943). Bowdoin Alumni Magazines. 17. https://digitalcommons.bowdoin.edu/alumni-magazines/17 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections and Archives at Bowdoin Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bowdoin Alumni Magazines by an authorized administrator of Bowdoin Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ) OVDOIN ALUMNUS NOVEMBER 1942 VOL. XVII NO. I WASSOOKEAG SCHOOL and WASSOOKEAG SCHOOL- CAMP The peace-time educational system developed at Wassookeag School-Camp and Wassookeag School from 1926 to 1928 has become a pattern for war. The colleges are operating on an accelerated schedule ; the draft is digging deeper into the ranks of youth ; the stride of events is lengthening toward complete mobilization of man power. All this demands that we do more for boy power and do it quickly. The boy who previously entered college at eighteen, the candidate of average or better abil- ity, can and must enter college at seventeen. The boy who entered college at seventeen, the boy of outstanding ability, can and must enter at sixteen. Candidates for college can save a year without sacrificing sound standards if they begin not with the senior year in school, but with the freshman or sophomore year. Now more than ever be- fore we must look ahead surely and plan ahead thoroughly. -

Strolling Through Istanbul

STROWNO THROUGH 1ST ANBUL Long acknowledged to be the 'best travel guide to Istanbul' (Times of London), this classic of travel literature is now available in a larger format in hardback binding. The work is both a useful and informative guide to the city with major useful monuments described in detail in terms of the history and architecture. Although the main emphasis of the book is on the Byzantine and Ottoman Antiquities, the city is not treated as a museum in the context of a living city. Itineraries are arranged so that each one takes the visitor to a different part of Istanbul. The late Hillary Sumner-Boyd was Professor of Humanities at Robert College, Istanbul, Turkey. 9780710307156 Strolling Through Istanbul A Guide To The City Size: 216 x 138mm Spine size: 33 mm Color pages: Binding: Hardback Page Intentionally Left Blank STROlliNG THROUGH 1ST ANBUL AGUIDE TO THE CITY HILARY SUMNER-BOYD JOHN FREELY I~ ~~o~I~~n~~~up LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 2003 by Kegan Paul Limited This edition first published in 2009 by Routledge Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 ThirdAvenue,NewYork,NY 10017USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informabusiness © Taylor & Francis, 2003 Transferred to Digital Printing 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Architecture Books & Folios Property of the Institute Of

Sale 497 Thursday, January 10, 2013 11:00 AM Architecture Books & Folios Property of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art, Northern California Chapter, & Other Owners Auction Preview Tuesday, January 8, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, January 9, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, January 10, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. -

University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

Commencement Weekend/May 17-19 University of Notre Dame EVENTS OF THE WEEKEND Sunday, May 19 Friday, Saturday and Sunday, May 17, 18 and 19, 1974 10:30 a.m. BOX LUNCH - Available at the North to and South Dining Halls. (Tickets must be Friday, May 17 1 p.m. purchased in advance.) 6:30 p.m. CONCERT - University Band - Memo 1 p.m. DIPLOMA DISTRIBUTION - Ath rial Library Mall. letic and Convocation Center - North (If weather is inclement, the concert will be Dome. Graduates only. cancelled.) 8 p.m. PLAY - "Beggar's Opera" by John Gay 1 :30 p.m. ACADEMIC PROCESSION b~gins - - O'Laughlin Auditorium- Saint Mary's Athletic and Convocation Center - North Dome. College. (Tickets may be purchased in ad vance.) 2 p.m. COMMENCEMENT - Athletic and Convocation Center - South Dome. Saturday, May 18 10 a.m. ROTC COMMISSIONING - Athletic and Convocation Center - South Dome. 2 p.m. UNIVERSITY RECEPTION- by the to University Administration in the Center for 3:30p.m. Continuing Education. Families of the grad uates are cordially invited to attend. 4:30p.m. GRADUATES ASSEMBLE for Academ ic Procession - Athletic and Convocation Center- North Dome. Graduates only. 4:45 p.m. ACADEMIC PROCESSION begins - Athletic and Convocation Center - North Dome. 5 p.m. BACCALAUREATE MASS - Athletic to and Convocation Center- South Dome. 6:15p.m. 6:30p.m. COCKTAIL PARTY AND BUFFET to SUPPER - Athletic and Convocation 8:30 p.m. Center- North Dome. (Tickets for each must be purchased in advance.) 8:30p.m. CONCERT- University of Notre Dame Glee Club - Stepan Center. -

Ph-War-Memorials-Evidence.Pdf

Evidence used for the London Assembly Planning and Housing Committee’s investigation into London’s War Memorials July 2009 Page 1 of 110 Contents Evidence is presented alphabetically by name of contributing individual or organisation Reference Individual or organisation Page Number Number (in this document) WMs/059 -Alleyn's School.................................................................................................................. 5 WMs/008 -Andrew Dismore MP for Hendon ................................................................................... 13 WMs/020 -Andrew Rosindell MP for Romford................................................................................ 14 WMs/024 -Bancrofts School, Woodford Green ............................................................................... 15 WMs/006 -Barnet Museum............................................................................................................... 17 WMs/050 -Beryl Nash....................................................................................................................... 18 WMs/042 -Canadian High Commission ............................................................................................ 19 WMs/025 -Colfe's School ................................................................................................................. 20 WMs/041 -Commonwealth War Graves Commission ....................................................................... 21 WMs/013 -Cyprus Area Projects Panel ........................................................................................... -

Kentucky Obituaries July 2001 Through December 2001 These Obituaries Are Gleaned from Mercer County Funeral Homes

Kentucky Obituaries July 2001 through December 2001 These obituaries are gleaned from Mercer County funeral homes. They are included here because there are many references to places and people in Boyle County. Douglas Baker. Funeral services were held. Tuesday, ANNESS. Martha (Mattie) Anness, 97, of 851 South College September 4, at the Alexander and Royalty Funeral Home with Street, died Friday, September 28, 2001 at Harrodsburg Health Dr. Robert DeFoor and Rev. Monia Safley officiating. Burial Care Center. Born November 30, 1903 in Mercer County, she was in Spring Hill Cemetery. Pallbearers were Mark Stratton, was the daughter of late Ben and Nannie Leach Chumbley. Michael Stratton, Tim Ellis, Myron Ellis, Chad Ellis and Ronnie She was the widow of McKinley Anness. She was retired as Bailey. Honorary bearers were members of the Faith, Hope head of housekeeping at Beaumont Inn and was a member of and Love Sunday School Class. Expressions of sympathy the Harrodsburg Christian Church. Survivors include: one son, may take the form of donations to Heritage Hospice, PO Box McKinley Anness, Jr., Harrodsburg; three daughters, Nancy 1213, Danville, KY 40422; Harrodsburg Baptist Foundation, Martin, Harrodsburg, Irene Hambright, Belfont, PA, and Rosa PO Box 286, Harrodsburg, KY 40330 or to one’s favorite Votaw, Valdosta, GA; one sister, Bessie Osbourne, charity. Harrodsburg; 11 grandchildren and several great grandchildren. Funeral services were held Tuesday, October BAKER. William Raymond Baker, 59, of 1146 West Shelby Street, 2, at the Ransdell Funeral Chapel with Don Chase officiating. Junction City, died Thursday, August 2, 2001 at St. Joseph Burial was in Spring Hill Cemetery. -

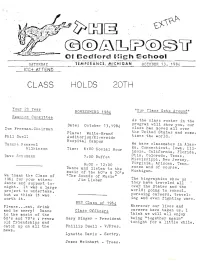

Class Holds 20Th

SATURDAY TEMPERANCE, MICHIGAN OCTOBER 13, 1984 ----------'-------~------ --~------'.~_...-.:.....;:..:;..::...:=-=-~...:...:::::..!.-.-.:.....:..-::::..-=----- Ice+ ATTEND CLASS HOLDS 20TH Your 20 Year HOMECOMING 1984 "OuY' Class Gets Arou~c." Reunion Committee As the class roster in the Date: October 13.1984 program will show you, our Don Freeman-Chairman class has moved allover l,- U -.... S Place: Waite-Brand t lie nlveu tates and some Phil Duell AUditorium/Riverside times the world. Hospital Campus Tamarrt Ke.navel We have classmates in Alas \hlkinson Time: 6:00 Social Hour ka, Connecticut, Iowa, Ill inois. California, Florida Dave Schumann 7:00 Buffet Ohio, Colorado, Texas, , Mississippi, New Jersey Ten~~ 9:00 - 12:00 Virginia, Arizona, Dance and listen to the essee and of course. music of the 60's & 70's Michigan. We thank the Class of ItThe Sounds of Music'l 1964 for your atten Jim Lieber The biographies show us da~ce and support to they have traveled all night. It was a large over the states and the project to undertake, world; going to school. but we think it was pursuing careers, travel worth it. ing and even fighting wars. BHS Class of 1964 Please ..• eat. drink ~~erever our lives and and be merry! Dance Class Officers careers have taken us, I to the music of the think we will all enjoy 60's and 70's; renew Gary Binger - President being "together again" old friendships and tonight for a little while. cat~r. up on all the Phillip Duell - V/Pres. news. Lynette Davis - Sectry. James Meinhart - Treas. BEDFORD HIGH SCHOOL FIGHT SONG CHEER, CHEER FOR OLD BEDFORD HIGH FOR IT'S THE BEST SCHOOL UNDER TH2 SKY, SING ITS PRAISES FAR AND WIDE, WE HONOR; WE LOVE: IT IS OUR PRIDE.