Polish Nobility and Its Heraldry: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Napoleon: the Man Behind the Myth

2019 VI Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth Adam Zamoyski London: William Collins, 2018 Review by: Jonathan North Review: Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth. By Adam Zamoyski. London: William Collins, 2018. ISBN 978-0-008-11607-1. xxiii + 752 pp. £30.00. he pharmacist Pierre-Irénée Jacob arrived in Madrid on 7 April 1809. The French had occupied the capital and were attempting to conquer the rest of the Iberian Peninsula in a war that would drain T blood and treasure from Napoleon’s empire for the next six years. The atmosphere in the city was strange and strained. On the one hand, the emperor Napoleon’s power seemed to have reached new heights and his sway, with an opulent Paris at its centre, extended from Galicia in Spain to Galicia in Poland. On the other, here was a land mired in an unnecessary conflict so brutal and costly that it would inspire Goya’s Disasters of War. Jacob, who had seen plenty of disasters on his way to Madrid, was relieved to have arrived and hurried to meet with his superior, Charles Jean Laubert. They were soon involved in a lively discussion about the man who had sent them to Spain. In his Journal et itinéraire de dix années de campagne, Jacob admitted that “the qualities of the emperor could not convince me to like him as a person,” and confessed that “his political mistakes, especially after 1808, had turned me against him.” Then Laubert, “after having praised some of the achievements of this extraordinary and highly intelligent man,” surprised Jacob by suddenly exclaiming “what a monster, my friend, what a monster.” In a sense, opinions on Napoleon have not moved on much since that frank exchange. -

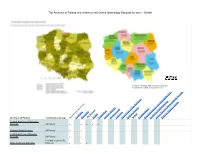

The Archives of Poland and Where to Find Online Genealogy Records for Each - Sheet1

The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Archives of Poland Territorial coverage Search theGenBaza ArchivesGenetekaJRI-PolandAGAD Przodek.plGesher Archeion.netGalicia LubgensGenealogyPoznan in the BaSIAProject ArchivesPomGenBaseSzpejankowskisPodlaskaUpper and Digital Szpejenkowski SilesianSilesian Library Genealogical Digital Library Society Central Archives of Historical Records All Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ National Digital Archive All Poland ✓ ✓ Central Archives of Modern Records All Poland ✓ ✓ Podlaskie (primarily), State Archive in Bialystok Masovia ✓ ✓ ✓ The Archives of Poland and where to find Online Genealogy Records for each - Sheet1 Branch in Lomza Podlaskie ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Pomerania State Archive in Bydgoszcz and Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Kuyavian-Pomerania (primarily), Greater Branch in Inowrocław Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), Świetokrzyskie, Łódz, National Archives in Częstochowa and Opole ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Pomerania (primarily), State Archive in Elbląg with the Warmia-Masuria, Seat in Malbork Kuyavian-Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gdansk Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Gdynia Branch Pomerania ✓ ✓ ✓ State Archive in Gorzow Lubusz (primarily), Wielkopolski Greater Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ Greater Poland (primarily), Łódz, State Archive in Kalisz Lower Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Silesia (primarily), State Archive in Katowice Lesser Poland ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Bielsko-Biala Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch in Cieszyn Silesia ✓ ✓ ✓ Branch -

From the History of Polish-Austrian Diplomacy in the 1970S

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI I, 2017 AGNIESZKA KISZTELIŃSKA-WĘGRZYŃSKA Łódź FROM THE HISTORY OF POLISH-AUSTRIAN DIPLOMACY IN THE 1970S. AUSTRIAN CHANCELLOR BRUNO KREISKY’S VISITS TO POLAND Polish-Austrian relations after World War II developed in an atmosphere of mutu- al interest and restrained political support. During the Cold War, the Polish People’s Republic and the Republic of Austria were on the opposite sides of the Iron Curtain; however, after 1945 both countries sought mutual recognition and trade cooperation. For more than 10 years following the establishment of diplomatic relations between Austria and Poland, there had been no meetings at the highest level.1 The first con- tact took place when the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bruno Kreisky, came on a visit to Warsaw on 1-3 March 1960.2 Later on, Kreisky visited Poland four times as Chancellor of Austria: in June 1973, in late January/early February 1975, in Sep- tember 1976, and in November 1979. While discussing the significance of those five visits, it is worth reflecting on the role of Austria in the diplomatic activity of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). The views on the motives of the Austrian politician’s actions and on Austria’s foreign policy towards Poland come from the MFA archives from 1972-1980. The time period covered in this study matches the schedule of the Chancellor’s visits. The activity of the Polish diplomacy in the Communist period (1945-1989) has been addressed as a research topic in several publications on Polish history. How- ever, as Andrzej Paczkowski says in the sixth volume of Historia dyplomacji polskiej (A history of Polish diplomacy), research on this topic is still in its infancy.3 A wide range of source materials that need to be thoroughly reviewed offer a number of 1 Stosunki dyplomatyczne Polski, Informator, vol. -

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

The Role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin Struggle for Independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1967 The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649. Andrew B. Pernal University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Pernal, Andrew B., "The role of Bohdan Khmelnytskyi and the Kozaks in the Rusin struggle for independence from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: 1648--1649." (1967). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6490. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6490 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE ROLE OF BOHDAN KHMELNYTSKYI AND OF THE KOZAKS IN THE RUSIN STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE FROM THE POLISH-LI'THUANIAN COMMONWEALTH: 1648-1649 by A ‘n d r e w B. Pernal, B. A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the University of Windsor in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Graduate Studies 1967 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Show Publication Content!

PAMIĘTNIKI SEWERYNA BUKARA z rękopismu po raz pierwszy ogłoszone. DREZNO. DRUKIEM I NAKŁADEM J. I. KRASZEWSKIEGO. 1871. 1000174150 0 (JAtCS V łubłjn Tych kilkanaście lat pamiętni ej szych młodośći mojej, Wspomnienia starego człowieka w upominku dla synów przekazuję. Jours heureux, teins lointain, mais jamais oublié. Où tout ce dont le charme intéresse à la vie. Egayait mes destins ignorés de l'envie. (Marie Joseph Chenier.)., Zaczęto d. 28. Czerwca 1845 r. Od lat kilku już ciągłe od was, kochani syno wie, żądania odbierając, abym napisał pamiętniki moje, zawsze wymawiałem się od tego, z pobudek następu jących. Naprzód, iż, podług mnie, ten tylko powinien zajmować się tego rodzaju opisami, kto, czyli sam bez pośrednio, czy też wpływając do czynności znakomi tych w kraju ludzi, dał się zaszczytnie poznać i do konywał rzeczy wartych pamięci. Powtóre : iż doszedł szy już późnego wieku, nie dałem sobie nigdy pracy notowania okoliczności i spraw, których świadkiem by łem, lub do których wpływałem. Trudno więc przy chodzi pozbierać w myśli kilkadziesiąt-letnie fakta. Lecz tłumaczenia moje nie zdołały zaspokoić was, i mocno upieracie się i naglicie na mnie o te niesz częśliwe pamiętniki. — To mi właśnie przypomniało, com wyczytał w opisie jakiegoś podróżującego: że w Chinach ludzie, którzy szukają wsparcia pieniężnego, mają zawsze w kieszeni instrumencik dęty — rodzaj piszczałek, który wrzaskliwy i przerażający głos wy- VIII daje. Postrzegłszy więc w swojéj drodze człowieka, którego powierzchowność obiecuje im zyskowną dona- tywę, zbliżają się do niego, idą za nim krok w krok i dmą w swój instrumencik tak silnie i tak długo, że rad nie rad, dla spokojności swojéj, obdarzyć ich musi. -

The Stolen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in World War Ii?

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Faculty Articles and Essays Faculty Scholarship 1999 The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? Barbara Tyler Cleveland State University, [email protected] How does access to this work benefit oy u? Let us know! Publisher's Statement Copyright permission granted by the Rutgers University Law Journal. Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/fac_articles Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Original Citation Barbara Tyler, The tS olen Museum: Have United States Art Museums Become Inadvertent Fences for Stolen Art Works Looted by the Nazis in Word War II? 30 Rutgers Law Journal 441 (1999) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Articles and Essays by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 30 Rutgers L.J. 441 1998-1999 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon May 21 10:04:33 2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=0277-318X THE STOLEN MUSEUM: HAVE UNITED STATES ART MUSEUMS BECOME INADVERTENT FENCES FOR STOLEN ART WORKS LOOTED BY THE NAZIS IN WORLD WAR II? BarbaraJ. -

Town Unveils New Flag & Coat of Arms

TOWN UNVEILS NEW FLAG & COAT OF ARMS For Immediate Release December 10, 2013 Niagara-on-the-Lake - Lord Mayor, accompanied by the Right Reverend D. Ralph Spence, Albion Herald Extraordinary, officially unveiled a new town flag and coat of arms today before an audience at the Courthouse. Following the official proclamation ceremony, a procession, led by the Fort George Fife & Drum Corps and completed by an honour guard from the 809 Newark Squadron Air Cadets, witnessed the raising of the flag. The procession then continued on to St. Mark’s Church for a special service commemorating the Burning of Niagara. “We thought this was a fitting date to introduce a symbol of hope and promise given the devastation that occurred exactly 200 years to the day, the burning of our town,” stated Lord Mayor Eke. “From ashes comes rebirth and hope.” The new flag, coat of arms and badge have been granted by the Chief Herald of Canada, Dr. Claire Boudreau, Director of the Canadian Heraldic Authority within the office of the Governor General. Bishop Spence, who served as Bishop of the Anglican Diocese of Niagara from 1998 - 2008, represented the Chief Herald and read the official proclamation. He is one of only four Canadians who hold the title of herald extraordinary. A description of the new coat of arms, flag and badge, known as armorial bearings in heraldry, is attached. For more information, please contact: Dave Eke, Lord Mayor 905-468-3266 Symbolism of the Armorial Bearings of The Corporation of the Town of Niagara-on-the-Lake Arms: The colours refer to the Royal Union Flag. -

Strengthened Air Defence

AUGUST 2020. NO 8 (27). NEWS FRENCH TROOPS IN LITHUANIA MARKED BASTILLE DAY NATO'S PRESENCE THE 7TH ROTATION: HANDLING AN UNEXPECTED CRISIS Strengthened air defence ON JULY 28 PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LITHUANIA GITANAS NAUSĖDA WAS ACCOMPANIED BY MINISTER OF NATIONAL DEFENCE RAIMUNDAS KAROBLIS, CHIEF OF THE DEFENCE STAFF OF THE LITHUANIAN ARMED FORCES MAJ GEN GINTAUTAS ZENKEVIČIUS AND COMMANDER OF THE LITHUANIAN AIR FORCE COL DAINIUS GUZAS ON A VISIT TO THE LITHUANIAN AIR FORCE BASE IN ŠIAULIAI TO FAMILIARISE WITH THE AIR DEFENCE CAPABILITIES LITHUANIA HAS AND TO MEET WITH THE SPANISH, BRITISH AND GERMAN AIRMEN CONDUCTING SPECIAL THE CURRENT ROTATION OF THE NATO AIR POLICING MISSION IN THE BALTIC STATES, AS WELL AS U.S. AND LITHUANIAN SOLDIERS. NAPOLEON‘S LITHUANIAN resident was shown the RBS70, tional Exercise Tobruq Legacy 2020 in Sep- FORCES. PART II Stinger, Grom missile air defence tember this autumn. systems operated by the Air Defence NASAMS is the most widely used mid- PBattalion, Sentinel and Giraffe surveillance range air defence system in NATO member radars, and elements of the NASAMS mid- states, and even for guarding the airspace over range air defence system delivered to Lithua- the White House, Washington. Lithuania has nia in June earlier this year. acquired the most recent, third generation, "Arrival of the NASAMS reinforces air NASAMS 3, its current users are still only defence of Lithuania and NATO’s eastern the Lithuanian Armed Forces and the Armed flank, all the components of the integrated Forces of Norway, the manufacturer. defence system are linked together, and The guests also viewed fighter aircraft the deterrence becomes stronger as a result," allies protect the Baltic airspace with: F18 Minister of National Defence R. -

Advantages, Shortcomings and Unused Potential. by Jack Carlson

Third Series Vol. V part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 218 Price £12.00 Autumn 2009 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume V 2009 Part 2 Number 218 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor +John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Noel COX, LL.M., M.THEOL., PH.D., M.A., F.R.HIST.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D. Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam INTERNET HERALDRY Advantages, Shortcomings and Unused Potential Jack Carlson In 1996, the Cambridge University Heraldic & Genealogical Society declared that 'genealogy and heraldry have both caught up with the latest computer technology' and that heraldists would soon prefer the internet to books: searchable heraldic databases and free, high-quality electronic articles and encyclopedias on the subject were imminent.1 Over the past thirteen years the internet's capabilities have likely surpassed what CUH&GS could have imagined. At the same time, it seems, the reality of heraldry's online presence falls somewhat short of the society's expectations. -

The Role of Charitable Activity in the Formation of Vilnius Society in the 14Th to Mid-16Th Centuries S.C

LITHUANIAN historical STUDIES 17 2012 ISSN 1392-2343 PP. 39–69 THE ROLE OF CHARITABLE ACTIVITY IN THE FORMATION OF VILNIUS SOCIETY IN THE 14TH TO MID-16TH CENTURIES S.C. Rowell ABSTRACT This article examines the development of charitable activity in the city of Vilnius and elsewhere in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania before the middle of the sixteenth century by studying the foundation of almshouses to care for the poor and destitute and foster the memory and salvation of pious benefactors. Almshouse foundations developed from increasing forms of practical piety within the GDL from the late fifteenth century, following earlier west European and Polish models. The first, dedicated to traditional patrons of such institutions, St Job and St Mary Magdalene, was founded by a Vilnius canon and medical doctor, Martin of Duszniki with the support of the monarch, Sigismund the Old, and his counsellors between 1518 and 1522. The almshouse swiftly became an established part of the city’s sacral topography. The fashion was adopted by Eastern Orthodox parishes in Vilnius too, and later spread to other confessional groups. Twelve charters are published for the first time in an appendix. Christian charity in public spaces flourished throughout Catholic Europe during the 13th to 15th centuries 1. Indeed, the first chari- table intitutions for the poor are known in England from the tenth century. It behoved the bishop elect on taking his oath of office to protect the poor and the sick 2. Providing lodging and food for the deserving poor over time became the function of almshouses, hospitalia.