University International

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Community Needs and Resources Assessment for the Port Aux Basques and Burgeo Areas

PRIMARY HEALTH CARE IN ACTION A Community Needs and Resources Assessment for the Port aux Basques and Burgeo Areas 2013 Prepared by: Danielle Shea, RD, M.Ad.Ed. Primary Health Care Manager, Bay St. George Area Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 4 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Page 6 Survey Overview Page 6 Survey Results Page 7 Demographics Page 7 Community Services Page 8 Health Related Community Services Page 10 Community Groups Page 15 Community Concerns Page 16 Other Page 20 Focus Group Overview Page 20 Port aux Basques: Cancer Care Page 21 Highlights Page 22 Burgeo: Healthy Eating Page 23 Highlights Page 24 Port aux Basques and Burgeo Areas Overview Page 26 Statistical Data Overview Page 28 Statistical Data Page 28 Community Resource Listing Overview Page 38 Port aux Basques Community Resource Listing Page 38 Burgeo Community Resource Listing Page 44 Strengths Page 50 Recommendations Page 51 Conclusion Page 52 References Page 54 Appendix A Page 55 Primary Health Care Model Appendix B Page 57 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Policy Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Port aux Basques/ Burgeo Area Page 2 Appendix C Page 62 Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Survey Appendix D Page 70 Port aux Basques Focus Group Questions Appendix E Page 72 Burgeo Focus Group Questions Community Health Needs and Resources Assessment Port aux Basques/ Burgeo Area Page 3 Executive Summary Primary health care is defined as an individual’s first contact with the health system and includes the full range of services from health promotion, diagnosis, and treatment to chronic disease management. -

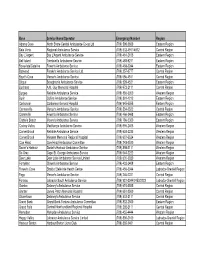

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 91 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, MARCH 4, 2016 No. 9 MINERAL ACT Mineral License 015780M Held by Iron Ore Company of Canada NOTICE Situate near Lac Virot On map sheet 23B/14 Published in accordance with section 62 of CNLR 1143/96 under the Mineral Act, cM-12 RSNL1990, as amended. A portion of license 019626M Held by Midland Exploration Inc. Mineral rights to the following mineral licenses have Situate near Strange Lake Area, West of Nain reverted to the Crown: On map sheet 24A/08, 14D/05 more particularly described in an application on file at Mineral License 023631M, 023632M, 023633M Department of Natural Resources. Held by Lushman, Gilbert Situate near Grey River, Southern NL Mineral License 016596M On map sheet 11P/11 Held by Alterra Resources Inc. Situate near Letitia Lake Mineral License 017069M On map sheet 13L/01 Held by North Atlantic Iron Corporation Situate near Goose Bay Mineral License 016601M On map sheet 13F/08 Held by Alterra Resources Inc. Situate near Isabella Falls Mineral License 011370M On map sheet 13L/02 Held by Nu Nova Energy Ltd. Situate near Kaipokok River Mineral License 016602M On map sheet 13K/10 Held by Alterra Resources Inc. Situate near Isabella Falls Mineral License 021759M On map sheet 13L/02 Held by Hicks, Darrin Situate near Lawn, Burin Peninsula Mineral License 016625M On map sheet 01L/14 Held by Martin, John Situate near Crooks Lake Mineral License 020469M On map sheet 13B/11 Held by Sokoman Iron Corp. -

January 2007

Volume XXV111 Number 1 January 2007 IN THIS ISSUE... VON Nurses Helping the Public Stay on Their Feet Province Introduces New Telecare Service New School Food Guidelines Sweeping the Nation Tattoos for You? Trust Awards $55,000 ARNNL www.arnnl.nf.ca Staff Executive Director Jeanette Andrews 753-6173 [email protected] Director of Regulatory Heather Hawkins 753-6181 Services [email protected] Nursing Consultant - Pegi Earle 753-6198 Health Policy & [email protected] - Council Communications Pat Pilgrim, President 2006-2008 Nursing Consultant - Colleen Kelly 753-0124 Jim Feltham, President-Elect 2006-2008 Education [email protected] Ann Shears, Public Representative 2004-2006 Nursing Consultant - Betty Lundrigan 753-6174 Ray Frew, Public Representative 2004-2006 Advanced Practice & [email protected] Kathy Watkins, St. John's Region 2006-2009 Administration Kathy Elson, Labrador Region 2005-2008 Nursing Consultant - Lynn Power 753-6193 Janice Young, Western Region 2006-2009 Practice [email protected] Bev White, Central Region 2005-2008 Project Consultant JoAnna Bennett 753-6019 Ann Marie Slaney, Eastern Region 2004-2007 QPPE (part-time) [email protected] Cindy Parrill, Northern Region 2004-2007 Accountant & Office Elizabeth Dewling 753-6197 Peggy O'Brien-Connors, Advanced Practice 2006-2009 Manager [email protected] Kathy Fitzgerald, Practice 2006-2009 Margo Cashin, Practice 2006-2007 Secretary to Executive Christine Fitzgerald 753-6183 Director and Council [email protected] Catherine Stratton, Nursing Education/Research -

Cajune Boats Podcast Transcript Otter.Ai

Cajune Boats Podcast Transcript Sat, 2/13 8:21AM 1:02:09 SUMMARY KEYWORDS boat, building, drift, fiberglass, river, dory, flip, wooden boat, big, bottom, panel, frames, design, skiff, fiberglass boats, plywood, advantages, feet, recurve, materials SPEAKERS Dave S, Jason, unknown speaker.... J Jason 00:01 And so I want something with some lower sides but the oarlocks have to be high. And I thought, you know, I think I can do this in a really aesthetic way and curved these sides and instead of having like a straight raised or lock, because at the time people had low sided boats with that raised or locked but it was just kind of a blocky affair. And so I built that first boat with for john and call it the recurve. And from there it was, it's been almost the only hole that I make anymore. Dave S 00:32 That was Jason cajon sharing the recurve story, a feature that has helped him stand out from the crowd. This and how he flipped over a drift boat and whitewater today on the wet fly swing fly fishing show. U unknown speaker.... 00:46 Welcome to the wet fly swing fly fishing show where you discover tips, tricks and tools from the leading names in fly fishing. Today, we'll help you on your fly fishing journey with classic stories covering steelhead fishing, fly tying and much more. Cajune Boats Podcast Transcript Page 1 of 26 Transcribed by https://otter.ai Dave S 01:02 Hey, how's it going today? Thanks for stopping by the fly fishing show. -

The Sharpie –A Personal View 2009

The Sharpie –A Personal View 2009 THE SHARPIE - A PERSONAL VIEW BY MIKE WALLER This article was originally published in Australian Amateur Boat Builder Magazine * * * * * To say that all flat bottomed boats are Sharpies is to say that all animals with four legs are horses. The statement simply does not hold water. It is true that most sharpies have flat bottoms, but the Sharpie is a unique design style which evolved over a specific period of history to fill a particular need, and to which certain well defined rules of design apply. The initial statement also denies the individuality of a multitude of other distinct hull ‘types’ such as the many and varied dory hull forms, skiffs, punts and hunting boats, and ‘near flat bottomed’ boats such as skipjacks, (not all Sharpies have absolutely flat bottoms, for that matter,) which developed in tandem with the Sharpie. A common misconception is that the Sharpie originated in Europe. It is true that many flat bottomed boats have existed in Europe over the years, notably the ‘Metre Sharpies’, but to say that the Sharpie evolved in Europe would make such great figures as Howard Chapelle, the well known maritime historian, turn in his grave. While there will always be differing opinions, the accepted history of the traditional Sharpie as we know it, is that it evolved on the eastern seaboard of the United States of America in the Oyster fisheries of Connecticut. It is largely down to the efforts of Howard Chapelle, who spent a lifetime documenting the development of the simple working boats of the United States, that we can credit most of our current knowledge of the rules and characteristics which define the traditional Sharpie as a distinct vessel style. -

Mantas, Dolphins and Coral Reefs – a Maldives Cruise

Mantas, Dolphins and Coral Reefs – A Maldives Cruise Naturetrek Tour Report 1 - 10 March 2018 Crabs by Pat Dean Hermit Crab by Pat Dean Risso’s Dolphin by Pat Dean Titan Triggerfish by Jenny Willsher Report compiled by Jenny Willsher Images courtesy of Pat Dean & Jenny Willsher Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Mantas, Dolphins and Coral Reefs – A Maldives Cruise Tour participants: Dr Chas Anderson (cruise leader) & Jenny Willsher (leader) with 13 Naturetrek clients Introduction For centuries the Maldives was a place to avoid if you were a seafarer due to its treacherous reefs, and this may have contributed to its largely unspoilt beauty. Now those very same reefs attract many visitors to experience the amazing diversity of marine life that it offers. Sharks and Scorpion fish, Octopus, Lionfish, Turtles and legions of multi-coloured fish of all shapes and sizes are to be found here! Add to that an exciting variety of cetaceans and you have a wildlife paradise. Despite the frustrating hiccoughs experienced by various members of the group in their travels, due to the snowy weather in the UK, we had a successful week in and around this intriguing chain of coral islands. After a brief stay in the lovely Bandos Island Resort (very brief for Pat and Stuart!), which gave us time for some snorkel practice, we boarded the MV Theia, our base for the next week. We soon settled into the daily routine of early morning and evening snorkels, daytimes searching for cetaceans or relaxing, and evening talks by Chas, our local Maldives expert. -

Executive Notes, May 8, 2015 from the NLTA

Newfoundland and Labrador Teachers’ Association EXECUTIVE NOTES May 8, 2015 our NLTA Provincial Executive met in St. John’s rebuild and recover from the earthquake devastation. Yon May 8, 2015. Executive Notes is a summary of • The NLTA will provide $500 to the NL Federation of discussions and decisions that occurred at these meetings. School Councils to assist with their AGM. For further information contact any member of Provincial • The NLTA will sponsor St. John’s Pride to the level of Executive or the NLTA staff person as indicated. $1,000 (silver sponsorship) pending a review of the promotional material for St. John’s Pride 2015. President’s Report Since the February meeting of Provincial Executive the For further information contact James Dinn, President President has attended numerous functions and visited or Don Ash, Executive Director. schools in St. John’s, Paradise, Conne River, Milltown, Ad Hoc Committee on Substitute Teachers English Harbour West, Harbour Breton, Lewisporte, • The NLTA will lobby the districts and the Department of Campbellton and Norris Arm. He presented NLTA’s pre- Education and Early Childhood Development to increase budget consultation brief to the Minister of Finance, met substitute teachers’ access to professional development with NLESD Trustees, met with the Minister of Finance sessions. regarding pension discussions, and with the Minister of • The NLTA will consider offering professional Education and Early Childhood Development regarding development sessions specifically for substitutes, as teacher allocation cuts. He attended the 2015 International well as consider the most viable way to offer these Summit on the Teaching Profession, the substitute teacher sessions to as many substitute teachers as possible. -

House of Assembly

HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY SECOND SESSION THIRTY-SEVENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NEWFOUNDLAND 1977 >l, .: V Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Assembly Honourable Gerald Ryan Ottenheimer Detailed Index of Verbatim Report 2nd Session Thirty-Seventh General Assembly of Newfound I and From Fehrur” 2n’,l°77 o ?Tovether 24th, 1°77 Compiled by: Sara J. MacGillivray Hansard Division House of Assembly TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGES OFFICIAL OPENING 37th GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NEWFOUNDLAND (2nd Session) 1—2 ADDRESS IN REPLY AND AMENDMENTS thereto 3—7 ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS 8-27 BILLS 28—45 BUDGET DEBATE 46 COMMITTEE OF SUPPLY (Estimates) 47-66 MISCELLANEOUS 67-70 ORAL QUESTIONS 71-132 PETITIONS 133—142 REPORTS, REGULATIONS, etc. 143—147 RESOLUTIONS 148—160 RULINGS 161—180 STATEMENTS (Ministerial) etc. 181—186 OFFICIAL CLOSING 187 OFFICIAL OPENING (PAGES 1—2) OFFICIAL OPENING - THIRTY-SEVENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NEWFOuNDLAND (SECOND SESSION) DATE - February 2, 1977 PAGES BOOK THRONE SPEECH - Read by it. Gov. G.A. Winter 1—14. 1. MOVER - C. Cross, Y.H.A. Bonavista North 15—19. “ SECONDER - H. Twomey, M.H.A. Exploits 20-23. “ H.M. LOYAL OPPOSITION LEADER - Hon. E.M. Roberts 23-45. Congratulations to Newfoundland’s first woman Rhodes Scholar (Miss Jacqueline Sheppard) 24. PREMIER OF NEWFOUNDLAND — Hon. F.D. Moores 45—64. MOTION:- “Select Committee be appointed to draft Address in Reply’:— C. Cross, M.H.A. Bonavista North H. Twomey, M.B.A. Exploits M. O’Brien, M.B.A. Ferryland 64. NOTICE OF RESOLUTIONS: (I. Strachan) ‘Select Committee to study and improve the role played by Labrador people” 66. -

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador

Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador ii Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Publication Series, Newfoundland and Labrador Region No. 0008 March 2009 Revised April 2010 Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador Prepared by 1 Intervale Associates Inc. Prepared for Oceans Division, Oceans, Habitat and Species at Risk Branch Fisheries and Oceans Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Region2 Published by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Newfoundland and Labrador Region P.O. Box 5667 St. John’s, NL A1C 5X1 1 P.O. Box 172, Doyles, NL, A0N 1J0 2 1 Regent Square, Corner Brook, NL, A2H 7K6 i ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2011 Cat. No. Fs22-6/8-2011E-PDF ISSN1919-2193 ISBN 978-1-100-18435-7 DFO/2011-1740 Correct citation for this publication: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2011. Social, Economic and Cultural Overview of Western Newfoundland and Southern Labrador. OHSAR Pub. Ser. Rep. NL Region, No.0008: xx + 173p. ii iii Acknowledgements Many people assisted with the development of this report by providing information, unpublished data, working documents, and publications covering the range of subjects addressed in this report. We thank the staff members of federal and provincial government departments, municipalities, Regional Economic Development Corporations, Rural Secretariat, nongovernmental organizations, band offices, professional associations, steering committees, businesses, and volunteer groups who helped in this way. We thank Conrad Mullins, Coordinator for Oceans and Coastal Management at Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Corner Brook, who coordinated this project, developed the format, reviewed all sections, and ensured content relevancy for meeting GOSLIM objectives. -

Audit Maritime Collections 2006 709Kb

AN THE CHOMHAIRLE HERITAGE OIDHREACHTA COUNCIL A UDIT OF M ARITIME C OLLECTIONS A Report for the Heritage Council By Darina Tully All rights reserved. Published by the Heritage Council October 2006 Photographs courtesy of The National Maritime Museum, Dunlaoghaire Darina Tully ISSN 1393 – 6808 The Heritage Council of Ireland Series ISBN: 1 901137 89 9 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Objective 4 1.2 Scope 4 1.3 Extent 4 1.4 Methodology 4 1.5 Area covered by the audit 5 2. COLLECTIONS 6 Table 1: Breakdown of collections by county 6 Table 2: Type of repository 6 Table 3: Breakdown of collections by repository type 7 Table 4: Categories of interest / activity 7 Table 5: Breakdown of collections by category 8 Table 6: Types of artefact 9 Table 7: Breakdown of collections by type of artefact 9 3. LEGISLATION ISSUES 10 4. RECOMMENDATIONS 10 4.1 A maritime museum 10 4.2 Storage for historical boats and traditional craft 11 4.3 A register of traditional boat builders 11 4.4 A shipwreck interpretative centre 11 4.5 Record of vernacular craft 11 4.6 Historic boat register 12 4.7 Floating exhibitions 12 5. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 12 5.1 Sources for further consultation 12 6. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF RECORDED COLLECTIONS 13 7. MARITIME AUDIT – ALL ENTRIES 18 1. INTRODUCTION This Audit of Maritime Collections was commissioned by The Heritage Council in July 2005 with the aim of assisting the conservation of Ireland’s boating heritage in both the maritime and inland waterway communities. 1.1 Objective The objective of the audit was to ascertain the following: -

The Hitch-Hiker Is Intended to Provide Information Which Beginning Adult Readers Can Read and Understand

CONTENTS: Foreword Acknowledgements Chapter 1: The Southwestern Corner Chapter 2: The Great Northern Peninsula Chapter 3: Labrador Chapter 4: Deer Lake to Bishop's Falls Chapter 5: Botwood to Twillingate Chapter 6: Glenwood to Gambo Chapter 7: Glovertown to Bonavista Chapter 8: The South Coast Chapter 9: Goobies to Cape St. Mary's to Whitbourne Chapter 10: Trinity-Conception Chapter 11: St. John's and the Eastern Avalon FOREWORD This book was written to give students a closer look at Newfoundland and Labrador. Learning about our own part of the earth can help us get a better understanding of the world at large. Much of the information now available about our province is aimed at young readers and people with at least a high school education. The Hitch-Hiker is intended to provide information which beginning adult readers can read and understand. This work has a special feature we hope readers will appreciate and enjoy. Many of the places written about in this book are seen through the eyes of an adult learner and other fictional characters. These characters were created to help add a touch of reality to the printed page. We hope the characters and the things they learn and talk about also give the reader a better understanding of our province. Above all, we hope this book challenges your curiosity and encourages you to search for more information about our land. Don McDonald Director of Programs and Services Newfoundland and Labrador Literacy Development Council ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the many people who so kindly and eagerly helped me during the production of this book.