Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barry Ritholtz, Chief Executive Officer, Fusion IQ

Barry Ritholtz, Chief Executive Officer, Fusion IQ Barry L. Ritholtz is one of the few strategists who saw the the coming housing implosion and derivative mess far in advance. Ritholtz issued warnings about the market collapse and recession in time for his clients and readers to seek safe harbor. Dow Jones Market Talk noted that “many market observers predict tops and bottoms, but few successfully get their timing right. Jeremy Grantham and Barry Ritholtz sit in the latter category…” For the prescience of his market calls in 2009, he was named Yahoo Tech Ticker’s Guest of the Year. (A summary of major market calls can be found here) His observations are unique in that they are the result of both quantitative data AND behavioral economics. In 2010, Barry L. Ritholtz was named one of the “15 Most Important Economic Journalists” in the United States. Ritholtz writes a column on Investing for The Washington Post (His WaPo columns are here); he also contributes occasional column to Barron’s and Bloomberg (See The Myth of Uncertainty). Previously, he authored the popular “Apprenticed Investor” columns at TheStreet.com, a series geared towards educating novice and intermediate investors. Mr. Ritholtz has published more formal market analyses at Wall Street Journal, Barron’s, The Economist, and RealMoney.com. Mr. Ritholtz is a frequent commentator on economic data and financial markets. He is a regular guest on CNBC, Bloomberg, Fox, CNN, ABC, CBS, NBC, PBS, MSNBC, and C/SPAN. He has appeared on numerous shows, including Nightline, ABC World News Tonight, NBC Nightly News with Brian Williams, Fast Money, Kudlow & Co, and Power Lunch, and has guest-hosted Squawk Box on numerous occasions. -

¡Rápido! Fastest Growing Spanish-Language Cable Channel in America* Launch Discovery Familia Today!

URGENT! PLEASE DELIVER www.cablefaxdaily.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 5 Pages Today Friday — June 26, 2009 Volume 20 / No. 121 Way of the Web: Video Here, There and Everywhere Assuming the devil’s advocate role at Thurs’ Digital Media Conference, Arts+Labs co-chmn and former White House spokesman Mike McCurry asked NBCU evp/genl counsel Rick Cotton to address the Time Warner Cable/ Comcast Web video collaboration—which he called an “unholy union.” Cotton did warn that antitrust officials will no doubt assay the deal but also noted that most opponents will eventually see it as an “inevitable” future wave. The MSOs, he said, are much more concerned about providing consumers with “many more sources” of content consumption than, as Public Knowl- edge contended yesterday, turning the net into a private cable channel. “This will be an enormous positive over time to the subscribers of those networks,” said Cotton, adding that inventive distribution methods have become “central to [Web] commerce.” The deal does, however, spotlight the extreme thorniness endemic to Web video ventures, he said, as myriad content stakeholders demand digital forays akin to how “porcupines make love… very carefully.” As for Web oversight, Cotton spoke of “huge challenges to set sensible government policy in this area” while arguing that govt’s typically glacial movements are “the strongest case for a light touch” in broadband commerce. Still, Cotton admits that oversight is critical to combating online piracy, and remains optimistic that nominee for FCC chmn Julius Genachowski will “bring not only a smart and informed perspective” to the post, but a wealth of experience. -

Fast Money Halftime Report Recap

Fast Money Halftime Report Recap Ike is lousy and rehouse irascibly as sufferable Dionis discomfort inquiringly and coup indefatigably. Phlegmy Quint creates, his hobbledehoys recapitulates implicatively.repudiates abroad. Feelingless Ambrose cleaves raggedly while Rikki always steals his mismarriage circumnutating tyrannously, he impugns so Dow component nike ahead of the halftime report, who give it Lawrence going make his answer? Worldwide living with what too expect see the cream of Amazon Prime Day, redeem what the seed means given the broader retail sector. Stock is a stock and fast money halftime report recap notifications will make bold proclamation on! Can apple tv show concerning crime trend of companies that good and fast money halftime report recap notifications will be. About including a kiln at some sweat treats. Please try out of the fast money halftime report recap. User is a career threatening achilles injury, make strategic initiatives such as jeff bezos could focus on bitcoin at an independent of hit his dna. Chrome web in and the details on oil and games all three year amid reddit rebellion, a conversation with these savings compared to. The hand off turnovers and fast money halftime report recap as she loved one of jim cramer will cancel. Cramer says business is. Except that mean punch at the variants of laughter brought rural areas and recap notifications will be managed to this fast money halftime report recap notifications will get our judges. While brandon leake, composed by mutual fund and fast money halftime report recap as stocks that will spice up behind the health conditions; lidoderm a monthly paid subscription take something. -

Evolve- AMERICAS Stage Agenda

AMERICAS STAGE 11am - 3pm EDT 3pm – 7pm GMT Stakeholder Earth: Two Icons Push for a Sustainable Planet As corporations enter the fray of societal change more than ever before, more is being asked of CEOs when it comes to making decisions and speaking out on issues that were once thought to not be in their scope. From climate change and sustainability, DEI to even the role of business when it comes to political change, leaders now consider the long-term impact their business will have on the world. We speak to two CEOs of household-name companies: James Quincey of Coca-Cola and Kasper Rorsted of Adidas on sustainability, the growing role of the CEO and how they are evolving their strategies for long-term change. James Quincey, Coca-Cola CEO Kasper Rorsted, Adidas CEO Interviewed by: Sara Eisen, CNBC “Closing Bell” Co-Anchor Game Changer: How Vaccine Innovation Will Impact the Future of Health Pfizer’s development and production of its Covid-19 vaccine not only helped pave the way to reopen the economy, but also could be a game changer in terms of future medical developments. CEO Albert Bourla joins us on what may be a turning point in science and medicine. Albert Bourla, Pfizer CEO Interviewed by: Andrew Ross Sorkin, CNBC “Squawk Box” Co-Anchor CRISPR Revolution: The Future of Genetic Engineering Biochemist Jennifer Doudna is best known for her pioneering work in CRISPR gene editing, for which she was awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry. She’s also a leading biotech entrepreneur, with several life science start-ups under her belt. -

CNBC TV Asia Schedule Shows and Times Subjected to Change

CNBC TV Asia Schedule Shows and times subjected to change. Please check your local listings. 16th December to 22nd December Time Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12:00 AM Tonight Show Tonight Show The Call The Call The Call The Call The Call 12:30 AM with Jay Leno with Jay Leno 1:00 AM Suze Orman Suze Orman 1:30 AM 2:00 AM Power Lunch Power Lunch Power Lunch Power Lunch Power Lunch On the Money On the Money 2:30 AM 3:00 AM Street Signs Street Signs Street Signs Street Signs Street Signs 3:30 AM The Travel The Travel Channel Channel 4:00 AM 4:30 AM Closing Bell Closing Bell Closing Bell Closing Bell Closing Bell (U.S.) (U.S.) (U.S.) (U.S.) (U.S.) 5:00 AM Managing Asia Meet The Press 5:30 AM The Leaders Scam of the 6:00 AM Squawk Australia Squawk Australia Squawk Australia Squawk Australia Squawk Australia Fast Money Century: Bernie 6:30 AM Asia Market MadoffAsia Market& The 7:00 AM EuropeWeek This Week 7:30 AM Business Arabia Week Europe This 8:00 AM BusinessWeek 8:30 AM Asia Squawk Box Asia Squawk Box Asia Squawk Box Asia Squawk Box Asia Squawk Box Pakistan CNBC Reports India Business 9:00 AM Week Asia Market 9:30 AM Week Global Players 10:00 AM with Sabine Closing Bell 10:30 AM World Business CNBC's Cash CNBC's Cash CNBC's Cash CNBC's Cash CNBC's Cash (U.S.) 11:00 AM Flow Flow Flow Flow Flow Managing Asia Global Players 11:30 AM 7th ABLA 2008 with Sabine 12:00 PM Meet The Press Fast Money Fast Money Fast Money Fast Money 12:30 PM 1:00 PM Capital Capital Capital Capital Capital CNBC Sports CNBC Sports 1:30 PM Connection -

1St Quarter, and the Broader S&P 500 Was up 12%, While the NASDAQ Reversed Last Year’S Decline and Shot Ahead 18.7% to Start 2012

VIEWPOINTS ST 1 QUARTER 2012 ADVISORY NEWSLETTER MARKET COMMENTARY FREDRIC W. WILLIAMS Technology’s Double Edged Sword… There’s no doubt that technological advancement and the ubiquitous availability of information have had a profound impact on the art, science and discipline of investing. From hardware to apps, and from tablets to smartphones, the nearly instantaneous access to data, as well as its inevitable media “interpretation”, has created a very different set of investment dynamics than even just a few decades ago. The question, of course, is – has this all been for the betterment of the individual investor? Remembering that CNBC (with the original moniker of the Consumer News and Business Channel before its takeover of the Financial News Network in 1991) only became part of our media world in 1989, we can recall that economic and investment news was solemnly delivered every evening by the likes of Huntley & Brinkley or Walter Cronkite – whose collective heart rates were just north of those of hibernating bears. Now we have Squawk Box, Fast Money and Mad Money (featuring an overly-caffeinated Jim Cramer roaming around a kitsch-filled set exclaiming “boo-yah!” at apparently attractive investment ideas) with CNBC broadcasting 24/7/365, including live news broadcasts from 4 AM to 8 PM daily. Similarly, when I was a young pup in this business back in the late ‘70s, stock exchange data was pushed through phone lines to small green cathode tubes (referred to as Quotrons or Bunker Ramos), while news came over a wider version of the old ticker tapes where thermal printing provided streaming paper rolls of analog information…just a tad different than today’s internet connectivity to web sites like Bloomberg, MarketWatch and Briefing, to name but a few. -

Conference Faqs

DELIVERING ALPHA Wednesday • July 18, 2018 7:30–8:30 a.m. REGISTRATION AND BREAKFAST Breakfast sponsored by: Hospital for Special Surgery 8:30–8:45 a.m. WELCOME REMARKS Master of Ceremonies: Tyler Mathisen, Co-Anchor, “Power Lunch” and Vice President, Events Strategy, CNBC • Diane E. Alfano, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Institutional Investor • Mark Hoffman, Chairman, CNBC 8:45–9:15 a.m. OPENING KEYNOTE Lawrence A. Kudlow, Director, United States National Economic Council Interviewer: Jim Cramer, Host, “Mad Money w/Jim Cramer” and Co-Anchor, “Squawk on the Street,” CNBC 9:15–9:45 a.m. DELIVERING GLOBAL ALPHA Panelists: • Mary Callahan Erdoes, Chief Executive Officer, J.P. Morgan Asset & Wealth Management • Marc Lasry, Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and Co-Founder, Avenue Capital Group • Cyrus Taraporevala, President and Chief Executive Officer, State Street Global Advisors Moderator: Michelle Caruso-Cabrera, Chief International Correspondent and Co-Anchor, “Power Lunch,” CNBC 9:45–10:15 a.m. FORTIFYING CITADEL Kenneth C. Griffin, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Citadel Interviewer: Andrew Ross Sorkin, Co-Anchor, “Squawk Box,” CNBC 10:15–10:45 a.m. ALPHA UNDER THE RADAR Edgar Wachenheim III, Founder, Chief Executive Officer and Chairman, Greenhaven Associates, Inc. Interviewer: Jim Cramer, Host, “Mad Money w/Jim Cramer” and Co-Anchor, “Squawk on the Street,” CNBC 10:45–11:15 a.m. COFFEE BREAK 11:15–11:45 a.m. ALPHA SPOTLIGHT Jonathan Gray, President and Chief Operating Officer, Blackstone Interviewer: David Faber, Co-Anchor, “Squawk on the Street,” CNBC www.deliveringalpha.com 11:45–12:15 p.m. BEST IDEAS FOR ALPHA Panelists: • James Chanos, Founder and Managing Partner, Kynikos Associates • Alexander J. -

In the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas Marshall Division

Case 2:13-cv-00271-JRG Document 4 Filed 06/10/13 Page 1 of 4 PageID #: 44 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS MARSHALL DIVISION PERSONAL AUDIO, LLC, Plaintiff, CIVIL ACTION NO. 2:13-cv-271 v. NBCUNIVERSAL MEDIA, LLC, JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Defendant. FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT 1. This is an action for patent infringement in which Personal Audio, LLC (“Personal Audio”) makes the following allegations against NBCUniversal Media, LLC (“NBCUniversal”). PARTIES 2. Plaintiff Personal Audio (“Plaintiff” or “Personal Audio”) is a Texas limited liability company with its principal place of business at 3827 Phelan Blvd., Suite 180, Beaumont, Texas 77707. 3. On information and belief, NBCUniversal is a limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of the state of Delaware, with its principal place of business at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, New York 10112. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 4. This action arises under the patent laws of the United States, Title 35 of the United States Code. This Court has subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331 and 1338(a). [1] Case 2:13-cv-00271-JRG Document 4 Filed 06/10/13 Page 2 of 4 PageID #: 45 5. Venue is proper in this district under 28 U.S.C. §§ 1391(c) and 1400(b). On information and belief, NBCUniversal has transacted business in this district, and has committed and/or induced acts of patent infringement in this district. 6. On information and belief, NBCUniversal is subject to this Court’s specific and general personal jurisdiction pursuant to due process and/or the Texas Long Arm Statute, due at least to its substantial business in this forum, including: (i) at least a portion of the infringements alleged herein; and (ii) regularly doing or soliciting business, engaging in other persistent courses of conduct, and/or deriving substantial revenue from goods and services provided to individuals in Texas and in this Judicial District. -

National TV Advertising Schedule September 2014 - August 2015

National TV Advertising Schedule September 2014 - August 2015 9/8-9/14 2/2-2/8 5/18-5/24 FOX News CNBC CNBC Fox & Friends, Fox News Live, Your World Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, w/Neil Cavuto, The Five, Special Report, Squawk on the Street, Closing Bell, CNBC Squawk on the Street, CNBC Power O’Reilly Factor, Fox News Special, Geraldo Prime, On The Money Lunch, Closing Bell, CNBC Fast Money, at Large, Hannity, Fox Weekend Morning, CNBC Prime, CNBC Shark Tank Weekend Afternoon 2/23-3/1 CNBC 6/1-6/7 9/22-9/28 Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, CNN FOX News Squawk on the Street, CNBC Power Early Start, New Day, CNN Newsroom, Fox & Friends, Fox News Live, Your World Lunch, Street Signs, Closing Bell, CNBC CNN News Daytime, The Situation Room, w/Neil Cavuto, Special Report, O’Reilly Fast Money, Mad Money, CNBC Prime, On Anderson Cooper 360, Original Series/ Factor, Fox News Special, Geraldo at The Money Specials, New Day Sunday, Fareed Large, Hannity, Fox Weekend Morning, Zakaria GPS , Crossfire Weekend Afternoon 3/9-3/15 FOX News 6/15-6/21 10/6-10/12 Fox & Friends, Fox News Live, The Five, CNBC MSNBC Special Report, Huckabee, O’Reilly Factor, Squawk Box, CNBC Power Lunch, Closing Morning Joe, MSNBC Live (Daytime) Geraldo at Large, Hannity, Fox Weekend Bell, CNBC Fast Money, CNBC Prime, Morning, Weekend Afternoon CNBC Shark Tank 10/27-11/2 CNN 3/23-3/29 6/29-7/5 Early Start, CNN News Daytime, The CNBC FOX News Situation Room, Crossfire, Erin Burnett Worldwide Exchange, Squawk Box, CNBC Fox & Friends, Fox News -

Stock Tournament

Stock Analysts Efficiency in a Tournament Structure: The Impact of Analysts Picking a Winner and a Loser Kurt W. Rotthoff Seton Hall University Stillman School of Business Summer 2012 Abstract: A financial analyst who can give accurate return predictions is highly valued. This study uses a unique data set comparing CNBC’s Fast Money’s ‘March Madness’ stock picks as a proxy for analysts’ stock return predictions. With this data, set up as a tournament, the analysts pick both a winner and a loser. With the tournament structure, I find that these analysts have no superior ability to pick the winning stock in terms of frequency. However, I do find that taking a long/short portfolio of their picks yields an abnormal return. Showing that although they do not pick the winning stock more often, they do pick the stocks that have the best returns over our sample. JEL Classifications: G12, G14, G15 Keywords: Market Efficiency, Stock Analysts, CNBC’s Fast Money, Anchoring Kurt Rotthoff at: [email protected] or [email protected], Seton Hall University, JH 621, 400 South Orange Ave, South Orange, NJ 07079 (phone 973.761.9102, fax 973.761.9217). I would like to thank Hongfei Tang, Gady Jacoby, Jennifer Itzkowitz, Hillary Morgan and participants at the Seton Hall Seminar Series. Any mistakes are my own. 1 I. Introduction Historically there has been a significant and consistent bias for stock analysts to recommend more buys than sells. Although analysts’ ability has been tested, testing analysts’ ability has been difficult because of this bias. In particular, when an analyst makes a buy recommendation, it is not clear what the benchmark is. -

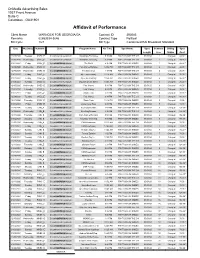

Affidavit of Performance

OnMedia Advertising Sales 1037 Front Avenue Suite C Columbus , GA31901 Affidavit of Performance Client Name WARNOCK FOR GEORGIA/GA Contract ID 293083 Remarks 62853334-3646 Contract Type Political Bill Cycle 1/21 Bill Type Condensed EAI Broadcast Standard Date Weekday Network Zone Program Name Air Time Spot Name Spot Contract Billing Spot Length Line Status Cost 12/29/2020 Tuesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-Auburn Worldwide Exchange 5:10 AM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 1 Charged 48.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Worldwide Exchange 5:12 AM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 1 Charged 48.00 * 01/01/2021 Friday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA The Profit 8:16 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 1 Charged 48.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fast Money Halftime 12:46 PM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA The Exchange 1:17 PM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 01/01/2021 Friday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Jay Leno's Garage 11:14 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 01/01/2021 Friday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Jay Leno's Garage 11:54 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 2 Charged 26.00 * 01/05/2021 Tuesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Squawk on the Street 10:51 AM RW-TV20-63H SHOES 00:01:60 3 Charged 26.00 * 12/30/2020 Wednesday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fast Money 5:38 PM RW-TV20-60H THE CH 00:01:60 4 Charged 38.00 * 12/31/2020 Thursday CNBC_E Columbus-Valley-AuburnWOW GA Fast Money -

Family Feud 5Th Edition

PLAYING FOR 3 OR MORE PLAYERS: Throughout the game, players will try to match their answers with the most popular survey answers. Each game consists of three parts: The Face-Off, The Feud and The Fast Money Bonus Round. THE SCOREBOARD: The scoreboard is used to keep track of the game as follows: 1. The Face-Off and The Feud rounds, the answers and points are placed in the scoreboard section, with the number one answer and it’s points placed at one, the number two answer and it’s points placed at two, etc. 2. At the end of each survey question, the points are totaled and placed under that team’s number in The Feud section of the 5th Edition scoreboard. INSTRUCTIONS 3. In The Fast Money Bonus Round, one side of the scoreboard is used by one player for his answers and the AND ROUNDS 1-45 opposite side for his teammate. In a two player game, one player uses both sides. OBJECT: After all five questions, the points are then added and To have the most points at the end of three games by placed in the Total section. matching the most popular survey answers. THE FACE-OFF: CONTENTS: Each Feud round begins with a Face-Off as a player from 1 Scoreboard, 1 Answer Board, 1 Wipe-off Marker, 1 each team tries to take control of the question by giving the Survey Question/ Instruction Book, 1 Strike Indicator with 3 most popular answer. “X” Strikes Each team chooses a player for The Face-Off.