C:\Users\Ahuerta\Appdata\Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing?

Jews Control U.S.A., Therefore the World – Is That a Good Thing? By Chairman of the U.S. based Romanian National Vanguard©2007 www.ronatvan.com v. 1.6 1 INDEX 1. Are Jews satanic? 1.1 What The Talmud Rules About Christians 1.2 Foes Destroyed During the Purim Feast 1.3 The Shocking "Kol Nidre" Oath 1.4 The Bar Mitzvah - A Pledge to The Jewish Race 1.5 Jewish Genocide over Armenian People 1.6 The Satanic Bible 1.7 Other Examples 2. Are Jews the “Chosen People” or the real “Israel”? 2.1 Who are the “Chosen People”? 2.2 God & Jesus quotes about race mixing and globalization 3. Are they “eternally persecuted people”? 3.1 Crypto-Judaism 4. Is Judeo-Christianity a healthy “alliance”? 4.1 The “Jesus was a Jew” Hoax 4.2 The "Judeo - Christian" Hoax 4.3 Judaism's Secret Book - The Talmud 5. Are Christian sects Jewish creations? Are they affecting Christianity? 5.1 Biblical Quotes about the sects , the Jews and about the results of them working together. 6. “Anti-Semitism” shield & weapon is making Jews, Gods! 7. Is the “Holocaust” a dirty Jewish LIE? 7.1 The Famous 66 Questions & Answers about the Holocaust 8. Jews control “Anti-Hate”, “Human Rights” & Degraded organizations??? 8.1 Just a small part of the full list: CULTURAL/ETHNIC 8.2 "HATE", GENOCIDE, ETC. 8.3 POLITICS 8.4 WOMEN/FAMILY/SEX/GENDER ISSUES 8.5 LAW, RIGHTS GROUPS 8.6 UNIONS, OCCUPATION ORGANIZATIONS, ACADEMIA, ETC. 2 8.7 IMMIGRATION 9. Money Collecting, Israel Aids, Kosher Tax and other Money Related Methods 9.1 Forced payment 9.2 Israel “Aids” 9.3 Kosher Taxes 9.4 Other ways for Jews to make money 10. -

Who Owns the Network News

Who Owns The Network News Janus Capital Corporation owns 6% MUSIC American Recordings, Asylum Atlantic, Atlantic Classics, Atlantic Jazz, Atlantic Nashville, Atlantic National Amusements Inc. (68%) AOL/ Theater, Big Beat, Breaking, Coalition, Curb, East Murdoch family controls 30% GENERAL ELECTRIC West, Elektra, Giant, Igloo, Lava, Mesa/Bluemoon, AT&T owns 8% OTHER Maverick (w/Madonna), Modern, Nonsuch, Qwest, Strong Capital Management 9% BET Design Studio (w/G-III MOVIES 143 (joint venture), Reprise, Reprise Nashville, BOOKS Waddell & Reed Asset Management Co. 9% VIACOM INC Apparel Group, Ltd.) produces SPORTS 2000 revenues: $111.6 billion APPLIANCES TIME WARNER and distributes Exsto XXIV VII Warner Bros. (75% w/25% AT&T), New Line 2000 revenues: $36.2 billion Revolution, Sire, Strickly Rhythm (joint venture), News America imprints include HarperCollins, (all owned 25% w/29% AT&T and 46% CABLEVISION) Walt Disney Company clothing and accessories GE, Hotpoint, Monogram, Profile and other Cinema, Fine Line Features; Castle Rock Teldec, Warner Nashville, Warner Alliance, Warner NEWS CORPORATION Regan Books, William Morrow and Avon; Madison Square Garden Arena and Theater; 2000 Revenues: $25.4 billion brand name appliances; Light bulbs and Entertainment; Warner Bros. joint ventures Resound, Warner Sunset, Other intrests include: 2000 Revenues: $14 billion Zondervan, largest commercial Bible imprint Management and operation of Hartford Civic lighting fixtures THE WALT DISNEY include Bel-Air Entertainment (w/Canal+), Warner/Chappell Music (publishing), -

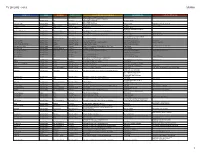

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of "(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. Otherivise, all joint copyright owners are listed. Date toto Claimant's Name City State Recvd. In Touch Ministries, Inc. Atlanta Georgia 7/1/06 Sante Fe Productions Albuquerque New Mexico 7/2/06 3 Gary Spetz/Gary Spetz Watercolors Lakeside Montana 7/2/06 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Hortus, Ltd. Little Rock Arkansas 7/3/06 6 Public Broadcasting Service (joint claim) Arlington Virginia 7/3/06 Western Instructional Television, Inc. Los Angeles Califoniia 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Devotional Television Broadcasts) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Syndicated Television Series) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 10 Berkow and Berkow Curriculum Development Chico California 7/3/06 11 Michigan Magazine Company Prescott Michigan 7/3/06 12 Fred Friendly Seminars, Inc. New York Ncw York 7/5/06 Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York dba Columbia University Seminars 13 on Media and Society New York New York 7/5/06 14 The American Lives II Film Project LLC Walpole Ncw Hampshire 7/5/06 15 Babe Winkelman Productions, Inc. Baxter Minnesota 7/5/06 16 Cookie Jar Entertainment Inc. Montreal, Quebec Canada 7/5/06 2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of."(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. -

Los Medios De Comunicacion

LOS MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN, A EXAMEN UNA NUEVA PERSPECTIVA Humberto Martínez-Fresneda Osorio, Javier Davara Torrego y Miguel Ortega de la Fuente MADRID, 2005 Quedan todos los derechos reservados. Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial. Primera edición: Septiembre de 2005. © 2005. Humberto Martínez-Fresneda Osorio, Javier Davara Torrego, Miguel Ortega de la Fuente. © Editorial Universidad Francisco de Vitoria. Ctra. Pozuelo-Majadahonda, Km. 1,800 28223 Pozuelo de Alarcón (Madrid) Teléfono: 91 709 14 00. Fax: 91 351 17 16 Para más información: www.fvitoria.com Dep. Legal: M. 38.786-2005 ISBN: 84-89552-89-4 Imprime: Gráficas Arias Montano, S. A. 28935 MÓSTOLES (Madrid) ÍNDICE Págs. INTRODUCCIÓN ............................................................................................ 11 PARTE I: LOS MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN Y SU PAPEL EN LA SOCIEDAD CAPÍTULO 1. La sociedad mundializada 1. El salto tecnológico ............................................................................. 17 2. Globalización y antiglobalización ...................................................... 20 3. La obsesión por el igualitarismo y el pensamiento único ............... 22 4. Lo políticamente correcto y el pensamiento débil ........................... 24 5. La fragilidad de la razón .................................................................... 26 6. Alumbrando un resquicio de esperanza ........................................... 27 CAPÍTULO 2. El concepto de Comunicación 1. Visiones actuales ................................................................................ -

New Line Cinema, Jackie Chan, and the Anatomy of an Action Star Jesse

New Line Cinema, Jackie Chan, and the Anatomy of an Action Star Jesse Balzer A Thesis in the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April, 2014 © Jesse Balzer 2014 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Jesse Balzer Entitled: New Line Cinema, Jackie Chan, and the Anatomy of an Action Star and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Read and approved by the following jury members: Charles Acland External Examiner Marc Steinberg Examiner Haidee Wasson Supervisor Approved by April 14, 2014 Catherine Russell Date Graduate Program Director April 14, 2014 Catherine Wild Date Dean of Faculty Balzer iii ABSTRACT New Line Cinema, Jackie Chan, and the Anatomy of an Action Star Jesse Balzer Jackie Chan’s Hollywood career began in earnest with the theatrical wide release of Rumble in the Bronx in early 1996 by independent studio New Line Cinema. New Line released two more Chan films – Jackie Chan’s First Strike (1997) and Mr. Nice Guy (1998) – after they were acquired by the media conglomerate Time Warner. These three films, originally produced and distributed by the Golden Harvest studio in Hong Kong, were distributed and marketed by New Line for release in North America. New Line reedited, rescored, and dubbed these films in order to take advantage of the significant marketing synergies of their conglomerate parents at Time Warner. -

CHRISTOPHER LEPS Kick the Can (Spec Ad) Director, Stunt Coordinator Alex Madison, Producer

FEATURE Spaceman Stunt Coordinator Stephen Nemeth, Producer Dance Camp Stunt Coordinator Jon M. Chu, Producer Book of Swords Stunt Coordinator Wayne Kennedy, Producer Torque Fight Coordinator (uncredited) Neal H. Moritz, Producer The Waiters 2nd Unit Director Kipp Tribble, Producer Clutch Stunt Coordinator Robert Stio, Producer TELEVISION Greenleaf (1 ep.) Cover Coordinator Al Dickerson, Producer RocketJump: The Show (1 ep.) Stunt Coordinator Freddie Wong, Producer Complications (2 eps.) Cover Coordinator Craig Siebels, Producer Burger King Star Wars commercial Fight Coordinator John Landis, Director Angel (1 ep.) Asst. Sword Coordinator Skip Schoolnik, Producer Worst Case Scenarios (1 ep.) Stunt Co-Coordinator Craig Piligian, Producer Mortal Kombat Conquest (14 eps.) Asst. Fight Coordinator (uncredited) Larry Kasanoff, Producer Out of the Blue Stunt Coordinator Sam Riddle, Producer Chase (spec ad) Director, Stunt Coordinator Alex Madison, Producer CHRISTOPHER LEPS Kick the Can (spec ad) Director, Stunt Coordinator Alex Madison, Producer DIRECTOR STUNT COORDINATOR SHORT FILM STUNTMAN Director, Producer, Writer, Editor Muse (2014) www.imdb.me/christopherleps Wholehearted (2012) www.christopherleps.com Century of Light (2011), [email protected] Ed & Vern’s Rock Store (2008) Cop Sign (2005) 818 . 618 . 5661 Shadow (2004), Saber Duel (2003) Director, Producer, Editor Testing (2015) Amy and Elliot (2009) SPECIAL SKILLS AND ABILITIES Directing | Editing | Pre-Viz | Martial Arts & Weapons (30 years) | Fight Choreography | Driving Sword Work | Mo-Cap | Reactions | High Falls | Mini-Tramp | Wire Work | Air Rams & Ratchets BIO Over the past 27 years, I’ve had a unique adventure in the TV and film industry. My diverse career started at the Walt Disney Company in 1989, but my zeal for cinema was sparked by the movies seen in my youth. -

The Hollywood Cinema Industry's Coming of Digital Age: The

The Hollywood Cinema Industry’s Coming of Digital Age: the Digitisation of Visual Effects, 1977-1999 Volume I Rama Venkatasawmy BA (Hons) Murdoch This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2010 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. -------------------------------- Rama Venkatasawmy Abstract By 1902, Georges Méliès’s Le Voyage Dans La Lune had already articulated a pivotal function for visual effects or VFX in the cinema. It enabled the visual realisation of concepts and ideas that would otherwise have been, in practical and logistical terms, too risky, expensive or plain impossible to capture, re-present and reproduce on film according to so-called “conventional” motion-picture recording techniques and devices. Since then, VFX – in conjunction with their respective techno-visual means of re-production – have gradually become utterly indispensable to the array of practices, techniques and tools commonly used in filmmaking as such. For the Hollywood cinema industry, comprehensive VFX applications have not only motivated the expansion of commercial filmmaking praxis. They have also influenced the evolution of viewing pleasures and spectatorship experiences. Following the digitisation of their associated technologies, VFX have been responsible for multiplying the strategies of re-presentation and story-telling as well as extending the range of stories that can potentially be told on screen. By the same token, the visual standards of the Hollywood film’s production and exhibition have been growing in sophistication. -

Claimant's Name City State Recvd

2001 Satellite Copyright Claims 9ate No Claimant's Name City State Recvd. 1 Broadcast Music, Inc.(BMI) New York New York 07/01/02 11 Bonneville Holding Company, KSL-TV Salt Lake City Utah 07/01/02 e Multimedia Holdings Corporation KPNX-TV Multimedia Holdings Corporation KARE-TV Multimedia Holdings Corporation KSDK-TV Multimedia Holdings Corporation KUSA-TV Multimedia Holdings Corporation KXTV-TV Multimedia Holdings Corporation WKYC-TV The Detroit News, Inc. WUSA-TV Gannett Georgia, L.P. WXIA-TV Pacific and Southern Company, Inc. WTSP- McLcan Virginia 07/01/02 e TV Stephen J. Cannell Productions, Inc. Hollywood California 07/02/02 e Western International Syndication Los Angeles California 07/02/02 e Steve Rotfeld Productions, Inc. Bryn Mawr Pennsylvania 07/03/02 11 National Basketball Association New York New York 07/03/02 11 SFX Television Washington DC 07/0302 ll Kost Broadcast Sales Chicago Illinois 07/0302 11 - 10 Gunthy Renker Palm Desert California 07/0302 h PGA Tour, Inc. Ponte Vedra Beach Florida 07/03/02 h 12 Professional Golfers'ssociation of America Palm Beach Florida 07/03/02 h 13 Ladies Professional Golfers Association Daytona Beach Florida 07/03/02 11 14 National Football League New York New York 07/03/02 h U:)CARP)CLAIMS(SATELLITE2001.WPD 2001 Satellite Copyright Claims Bate No Claimant's Name City State Recvd. 15 Women's National Basketball Association Secaucus New Jersey 07/03/02 h 16 NFL Films Mt. Laurel New Jersey 07/03/02 h 17 (Non-Game) National Basketball Association New York New York 07/03/02 h Augusta National Gulf Club (Augusta 18 National) Augusta Georgia 07/03/02 h 19 National Hockey League ( Game) New York New York 07/03/02 20 Our Own Performance Society (OOPS) New York New York 07/05/02 e 21 TV Alabama, Inc. -

An Economic Analysis of the Prime Time Access Rule

BEFORE THE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In re: Review of the Prime Time Access Rule, Section 73.658 (k) of the Commission’s } MM Docket No. 94-123 Rules AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE PRIME TIME ACCESS RULE March 7, 1995 ECONOMISTS INCORPORATED WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTENTS I. Introduction……………………………...……………………………………………1 II. Is ABC, CBS or NBC Dominant Today? A. No single network dominates any market...........................................................5 B. Factors facilitating the growth of competing video distributors ................................................................................................7 1. Cable penetration ....................................................................................7 2. Number and strength of independent stations.........................................9 3. Other video outlets................................................................................12 C. Competing video distributors............................................................................13 1. New broadcast networks .......................................................................13 2. New cable networks..............................................................................16 3. First-run syndication .............................................................................17 D. Impact on networks of increased competition ..................................................18 1. Audience shares ....................................................................................18 -

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V. -

MAGAZINE Vol

July 1996 MAGAZINE Vol. 1, No. 4 ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE July 1996 The Great Adventures of Izzy — An Olympic Hero for Kids by Frankie Kowalski 35 A look at the making of the first TV special based on an Olympic games mascot. “So,What Was It Like?” The Other Side Of Animation's Golden Age” by Tom Sito 37 Tom Sito attempts to puncture some of the illusions about what it was like to work in Hollywood's Golden Age of Animation of the 1930s and 40s, showing it may not have been as wild and wacky as some may have thought. When The Bunny Speaks, I Listen by Howard Beckerman 42 Animator Howard Beckerman explains why, "Cartoon characters are the only personalities you can trust." No Matter What,Garfield Speaks Your Language by Pam Schechter 46 Attorney Pam Schechter explores the ways cartoon characters are exploited and the type of money that's involved. Festival Reviews and Perspectives: Cardiff 96 by Bob Swain 49 Zagreb 96 by Maureen Furniss 53 Film Reviews: The Hunchback of Notre Dame by William Moritz 57 Desert Island Series... The Olympiad of Animation compiled by Frankie Kowalski 61 Picks from Olympiad animators Melinda Littlejohn, Raul Garcia, July 1996 George Schwizgebel and Jonathan Amitay. News Tom Sito on Virgil Ross + News 63 Preview of Coming Attractions 67 © Animation World Network 1996. All rights reserved. No part of the periodical may be reproduced without the consent of Animation World Network. Cover: The Spirit of the Olympics by Jonathan Amitay 3 ANIMATION WORLD MAGAZINE July 1996 The Great Adventures of Izzy — An Film Roman’s version of Izzy. -

Turner Broadcasting System

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-K405 Annual report pursuant to section 13 and 15(d), Regulation S-K Item 405 Filing Date: 1996-03-21 | Period of Report: 1995-12-31 SEC Accession No. 0000950144-96-001095 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER TURNER BROADCASTING SYSTEM INC Mailing Address Business Address ONE CNN CENTER BOX ONE CNN CENTER CIK:100240| IRS No.: 580950695 | State of Incorp.:GA | Fiscal Year End: 1231 105366 100 INTERNATIONAL BLVD Type: 10-K405 | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-08911 | Film No.: 96537151 ATLANTA GA 30348-5366 ATLANTA GA 30303 SIC: 4833 Television broadcasting stations 4048271700 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document 1 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------- SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K (MARK ONE) [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 [FEE REQUIRED] FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 1995 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 [NO FEE REQUIRED] FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO ---------------- ---------------- COMMISSION FILE NO. 0-9334 Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) GEORGIA 58-0950695 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) ONE CNN CENTER 30303