FINAL\Richards Street PDF\RSA-Overview Doc PDF.Wpd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities, 1850-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources November 2019 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 Related Contexts and Evaluation Considerations 1 Other Sources for Military Historic Contexts 3 MILITARY INSTITUTIONS AND ACTIVITIES HISTORIC CONTEXT 3 Historical Overview 3 Los Angeles: Mexican Era Settlement to the Civil War 3 Los Angeles Harbor and Coastal Defense Fortifications 4 The Defense Industry in Los Angeles: From World War I to the Cold War 5 World War II and Japanese Forced Removal and Incarceration 8 Recruitment Stations and Military/Veterans Support Services 16 Hollywood: 1930s to the Cold War Era 18 ELIGIBILITY STANDARDS FOR AIR RAID SIRENS 20 ATTACHMENT A: FALLOUT SHELTER LOCATIONS IN LOS ANGELES 1 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities PREFACE These “Guidelines for Evaluating Resources Associated with Military Institutions and Activities” (Guidelines) were developed based on several factors. First, the majority of the themes and property types significant in military history in Los Angeles are covered under other contexts and themes of the citywide historic context statement as indicated in the “Introduction” below. Second, many of the city’s military resources are already designated City Historic-Cultural Monuments and/or are listed in the National Register.1 Finally, with the exception of air raid sirens, a small number of military-related resources were identified as part of SurveyLA and, as such, did not merit development of full narrative themes and eligibility standards. -

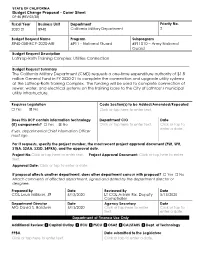

Lathrop-Roth Training Complex: Utilities Connection

STATE OF CALIFORNIA Budget Change Proposal - Cover Sheet DF-46 (REV 02/20) Fiscal Year Business Unit Department Priority No. 2020-21 8940 California Military Department 2 Budget Request Name Program Subprogram 8940-058-BCP-2020-MR 6911 - National Guard 6911010 – Army National Guard Budget Request Description Lathrop-Roth Training Complex: Utilities Connection Budget Request Summary The California Military Department (CMD) requests a one-time expenditure authority of $1.8 million General Fund in FY 2020-21 to complete the connection and upgrade utility systems at the Lathrop-Roth Training Complex. The funding will be used to complete connection of sewer, water, and electrical systems on the training base to the City of Lathrop’s municipal utility infrastructure. Requires Legislation Code Section(s) to be Added/Amended/Repealed ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. Does this BCP contain information technology Department CIO Date (IT) components? ☐ Yes ☒ No Click or tap here to enter text. Click or tap to enter a date. If yes, departmental Chief Information Officer must sign. For IT requests, specify the project number, the most recent project approval document (FSR, SPR, S1BA, S2AA, S3SD, S4PRA), and the approval date. Project No.Click or tap here to enter text. Project Approval Document: Click or tap here to enter text. Approval Date: Click or tap to enter a date. If proposal affects another department, does other department concur with proposal? ☐ Yes ☐ No Attach comments of affected department, signed and dated by the department director or designee. Prepared By Date Reviewed By Date COL Louis Millikan, J9 5/13/2020 LT COL Adam Rix, Deputy 5/13/2020 Comptroller Department Director Date Agency Secretary Date MG David S. -

June 2007 Adjutant General’S Department Responds to F-5 Tornado

Incident Expeditionary Black Hawk Response Emergency goes “shark Vehicle . .2 Medical hunting” . .12 PPllaaiinnss GGSystemuua a. .9rrddiiaann Volume 50 No. 5 Serving the Kansas Army and Air National Guard, Kansas Emergency Management, Kansas Homeland Security and Civil Air Patrol June 2007 Adjutant General’s Department responds to F-5 tornado The town of Greensburg, Kan., was almost totally destroyed by an F-5 tornado that ripped through several counties the night of May 4. (Photo by Sharon Watson) Town destroyed; Governor President Bush tours declares State of Disaster scenes of destruction Emergency for Greensburg By 1st Lt. Sean T. Linn, UPAR President George W. Bush spent several State and local agencies and volunteer donations center, a social services center hours in Greensburg on Wednesday, May 9, organizations responded to the devastation and a distribution center in Haviland. The arriving by helicopter to assess the damage. in Greensburg, Kan., caused by a tornado Salvation Army also established three can- The President’s first stop was the John that struck the community at approximately teens in Greensburg to feed storm victims Deere dealership to view the smashed and 10 p.m. on Friday, May 4, damaging or and rescue workers. overturned combines, tractors and imple- destroying 95 percent of the buildings in the The Kansas Division of Emergency ments. Several of these heavy machines town of approximately 1,500. Governor Management coordinated the response and had been picked up by the massive tornado Kathleen Sebelius declared a State of recovery operations of various state and and thrown across Highway 54. Disaster Emergency for Kiowa County. -

November 2002

Wilkening takes command of Guard National Guard, with 2,300 mem- Former Air Guard bers at state headquarters and commander is Truax Field in Madison, Mitchell Field in Milwaukee, and Volk Field states’s 29th AG near Camp Douglas; and a civil- ian workforce including the By Tim Donovan state’s Emergency Management At Ease Staff division. “It is an honor and privilege Gov. Scott McCallum passed to serve you and the men and the flag of the Wisconsin National women of the Wisconsin National Guard to a new commander in a Guard as the next adjutant gen- ceremony at the state headquar- eral,” Wilkening told the gover- ters Aug. 9, making Brig. Gen. Al nor before a standing-room-only Wilkening the state’s 29th adju- audience at the state headquar- tant general. ters armory. Wilkening succeeds Maj. “You have exhibited extraor- Gen. James G. Blaney, who held dinary leadership during some of the state’s top military spot for the most dynamic and demanding five years. times in our nation’s history and I “As I wish Jim Blaney well in look forward to engaging the chal- a long and happy retirement,” lenges that lie ahead,” Wilkening McCallum said. “I also look for- said. “I also look forward to serv- ward to working with Al ing in this new capacity with great Wilkening, who will continue the confidence because I am assum- strong leadership that makes our ing command of the very best mili- Brig. Gen. Al Wilkening is promoted to the rank of major general during the change of Wisconsin National Guard the tary organization in the nation.” command ceremony for the adjutant general of Wisconsin. -

Plains Guardianguardian

TAG visits National Honor Crisis City troops in Guard team shows off its Kosovo . .2 competition is facilities . .10 demanding . .7 PlainsPlains GuardianGuardian Volume 53 No. 1 Serving the Kansas Army and Air National Guard, Kansas Emergency Management, Kansas Homeland Security and Civil Air Patrol February 2010 State budget shortfalls force closure of 18 armories Maj. Gen. Tod Bunting, Kansas adjutant general, recently announced the names of “This was a difficult deci- the communities where 18 of 56 Kansas sion, but we had little National Guard armories will close in Feb- ruary 2010 due to state budget cuts. choice as the state budget Armories slated to be closed are in was reduced and we con- Atchison, Burlington, Chanute, Cherryvale, Council Grove, Fort Scott, Garden City, sidered what would be Garnett, Goodland, Horton, Kingman, necessary for long-term Larned, Phillipsburg, Russell, Sabetha, sustainment of armory op- Salina (East Armory), Troy and Winfield. The Salina East building will remain open erations statewide.” for Guard use, but armory operations will Maj. Gen. Tod Bunting be transferred to other armories. Armory personnel, community leaders, the adjutant general legislators and congressional staff affected by the impacted armories, as well as all necessary for long-term sustainment of ar- Adjutant General Department staff, were mory operations statewide,” said Bunting. notified prior to the public announcement. “When you factor in maintenance, re- Budget cuts and the need for long-term pairs and utilities, the real annual cost of sustainment of operations force closures keeping the remaining 38 armories open is The decision to close the facilities and $2.95 million,” Bunting explained. -

Times Spring 2015

SDF Times Spring 2015 COMMUNICATIONS Message from the President, BG(AK) Roger E. Holl: s Message from the President The Need Other News The State Guard Association of the United States is highly proactive in its News from the State Guards efforts to prepare State Defense Forces to respond to the needs of the states. In Word Search today’s environment, the world is a dangerous place. In addition, changing weather patterns are continuing to bring natural disasters which affect our citizens. There has never been a greater need for State Defense Forces to be UPCOMING EVENTS capable of augmenting the National Guard in time of emergencies in a highly October 29, 2015 professional manner. SGAUS Board Meet at 1600 Hanover, MD Strategic Planning October 30, 2015 The Strategic Planning Committee of the State Guard Association of the SGAUS JAG/Legal CLE Training United States will soon be contacting you to survey your thoughts on how SGAUS Hanover, MD can best serve every soldier in SGAUS and your State Defense Force. SGAUS is Oct 30 – Nov 1, 2015 concerned with every soldier, so please participate in the survey. In addition, the 2015 Annual Conference State Guard Association has a working group that is making recommendations for Hanover, MD changes to NGR 10-4. NGR 10-4 is the regulation which defines the relationship of Nov 18 – 21, 2015 State Defense Forces to the National Guard Bureau. SGAUS Chaplain Training Edinburgh, IN All State Defense Force Commanders should be involved in this NGR-10-4 analysis. This is a unique opportunity. -

State Arsenal & Armory

0MB Fon 10-900 USDI/NPS NHRP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB 1024-0018 PROPERTY NAME State Arsenal and Armory. Hartford. Connecticut Page 1 United States Department of the Interior National Register of Historic Places Registration Fon 1. NAME OF PROPERTY ^p " RECEIVED 2280 Historic Name: State Arsenal and Armory MAR ~ 4 1996 Other Name/Site Number: NA REGISTER Of HISTORIC PLACES tATIONAt PARK SERVICE 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 360 Broad Street_____________Not for publication: NA City/Town: Hartford_______________________ Vicinity: NA State:_CT County: Hartford___________ Code: 003 Zip Code: 06105 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private:__ Building(s): x Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:_x_ Site:__ Public-Federal:__ Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 ____ buildings ____ ____ sites _____ ____ structures _____ ____ objects __1_ ____ Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: NA Name of related multiple property listing:_NA_________________ 0MB Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NHRP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB 1024-0018 PROPERTY NAME State Arsenal and Armory. Hartford. Connecticut Page 2 United States Department of the Interior National Register of Historic Places Registration Fon 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets ___ does not meet the National Register,Criteria. -

Final Armory Historic Context

FINAL ARMORY HISTORIC CONTEXT ARMY NATIONAL GUARD NATIONAL GUARD BUREAU June 2008 FINAL HISTORIC CONTEXT STUDY Prepared for: Army National Guard Washington, DC Prepared by: Burns & McDonnell Engineering Company, Inc Engineers-Architects-Consultants Kansas City, Missouri And Architectural and Historical Research, LLC Kansas City, Missouri Below is the Disclaimer which accompanied the historic context when submitted to the NGB in draft form in 2005. Due to reorganization of the document prior to its finalization, the section in which Burns & McDonnell references below has been changed and is now Section II of the document, which is written in its entirety by Ms. Renee Hilton, Historical Services Division, Office of Public Affairs &Strategic Communications, National Guard Bureau. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND, AND METHODOLOGY ........................... 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 BACKGROUND............................................................................................. 1-1 1.3 SURVEY BOUNDARIES AND RESOURCES ............................................... 1-2 1.4 SURVEY OBJECTIVES................................................................................. 1-2 1.5 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................... 1-3 1.6 REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS.............................................................. 1-4 1.7 HISTORIC INTEGRITY ................................................................................ -

Guardsman Are US Postage Paid Not Necessarily the Official Views Oc Endorsed By, the US

Guardsma^^"•% LouisianM-«>!• •"»•«•••«a• ^m n VOLUME 6, NUMBER 1 JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1993 nquere By Artillery "Guiardsmen "OU'I Mil This newspaper is an Authorized Publication for members of the BULK RATE Louisiana National Guard. Contents of the Louisiana Guardsman are US Postage Paid not necessarily the official views oC endorsed by, the US. Government, Permit No 568 Dept. of Defense, Dept of the Army, or the Louisiana National Guard. New Orleans. LA 70130 Page 2 LOUISIANA GUARDSMAN JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1993 It is with profound regret that the Louisiana Army National Guard announces the untimely deaths of three Louisiana Na- tional Guardsmen. PFC Scott Joseph Annand Pvt 1st Class Scon Joseph Annand died November 17.1992 He was 19 years old Annand enlisted in the Louisiana Army National Guard October 10,1990. He was most recently assigned to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, (HHC), 1st Battalion, 156th Armor, as a petroleum supply specialist. He also served for I short time with HHC of the 22 5th Engineer Group and HHC of the 4th Battalion, 156th Infantry Annand was awarded the Army Service Ribbon upon completion of his Military Occupational Speciality Course He is survived by his parents, Newell and Cheryl Annand BG Edmund J. Giering, III SPC Robert Brian Harrell In January. Brig. Gen. EdmundJ. Giering. III. was promoted to that rank and assumed Spec Robert Bnan Hanell died November 7,1992 He was 23 years old the position of Deputy STARC Commander for the Louisiana Army National Guard.. Hanell enlisted in the Louisiana Anny National GuardApnl 21,1^X7 He was assigned Giering. -

SENATE BILL 479 by Gardenhire an ACT to Add Brigadier General Carl

<BillNo> <Sponsor> SENATE BILL 479 By Gardenhire AN ACT to add Brigadier General Carl E. Levi to the name of a National Guard Armory in Chattanooga. WHEREAS, many fine and honorable traditions have arisen from the deep wellspring of honor and bravery possessed by Tennesseans, but there is no finer tradition than that which gave Tennessee its nickname; and WHEREAS, the citizens of the Volunteer State have, throughout the years, willingly forsaken the comforts and securities of inaction by taking up arms against the enemies of this great nation, risking their lives and leaving their loved ones behind in order to honorably safeguard the freedoms and liberties guaranteed to all citizens of these United States and vanquishing those who threaten our way of life; and WHEREAS, one such courageous Volunteer is Brigadier General Carl E. Levi of the Tennessee National Guard, Retired, who devoted his career to defending our great nation; and WHEREAS, a graduate of Chattanooga High School, Brigadier General Carl Levi received his Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Chattanooga; he later received his Certified Municipal Financial Administrator certification from the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Center of Public Financial Administration; and WHEREAS, with an unwavering sense of duty and patriotism, Brigadier General Levi enlisted in the United States Army at the rank of private in 1952 and honorably served in active duty during the Korean War; he attended Field Artillery Basic and Advance School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and was an honor graduate of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, the U.S. -

A History of the Bellingham National Guard Armory 525 N

A HISTORY OF THE BELLINGHAM NATIONAL GUARD ARMORY 525 N. State Street, Bellingham, WA 98225 By Taylor Russell All pictures courtesy of the Whatcom Museum’s Photo Archives For thousands of years, the area surrounding Bellingham Bay was inhabited by the Coast Salish people. Local tribes such as the Lummi Indians made use of the natural waterways and abundant resources, like trees and fish. In the early 19th century, Euro-American settlers were attracted to these same resources and the Bay’s convenient location between the burgeoning metropolises of Vancouver, Victoria, and Seattle. The first permanent settlers, Captains Henry Roeder and Russell Peabody, arrived in December 1852 and opened a mill at Whatcom Creek. The environment and demographics rapidly changed as more mills and lumberyards, mines, and fish canneries sprouted along the shore, serviced by well- connected trade and transportation networks. Four separate towns developed around the bay, fueled in part by the miners, settlers, and entrepreneurs en route to the Fraser Canyon goldfields in nearby British Columbia. As more and more settlers flooded the Puget Sound area, Coast Salish people, many travelling from distant Canadian and Russian territories, frequently attacked the new town sites, disrupting Euro-Americans’ industries. This motivated the United States government to build military strongholds in the Northwest to protect the many settlements, like those at Port Townsend, Whidbey Island, and Bellingham Bay, from Indian attacks. In 1856, the US Army sent Captain George Pickett to build Fort Bellingham to defend the resources and Fort Bellingham, built in 1856. developing towns on the bay. The fort would be the first instance of a national military presence in the Bellingham area. -

Click Here to Download

PROFILE OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY • 2020 AUSA 1-214th Aviation Regiment and 1-3rd Attack Reconnaissance Battalion, 12th Combat Aviation Brigade, flying together and qualifying during Aerial Gunnery, Grafenwöhr Training Area on 20 July 2020 (U.S. Army photo by Sergeant Justin Ashaw). Developed by the Association of the United States Army RESEARCH, WRITING & EDITING GRAPHICS & DESIGN Ellen Toner Kevin Irwin COVER: A U.S. Army Special Operations Soldier The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information with 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement. (Airborne) loads a magazine during Integrated Training Exercise 3-19 at Marine Corps Air- ©2020 by the Association of the United States Army. All rights reserved. Ground Combat Center Twentynine Palms, Association of the United States Army California, 2 May 2019 (U.S. Marine Corps photo 2425 Wilson Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22201-3385 703-841-4300 • www.ausa.org by Lance Corporal William Chockey). | Contents F FOREWORD v 1 NATIONAL DEFENSE 1 2 LAND COMPONENT 9 3 ARMY ORGANIZATION 21 4 THE SOLDIER 31 5 THE UNIFORM 39 6 THE ARMY ON POINT 49 7 ARMY FAMILIES 63 8 ARMY COMMANDS 71 9 ARMY SERVICE COMPONENT COMMANDS 79 10 DIRECT REPORTING UNITS 95 M MAPS 103 Contents | iii The Association of the United States Army (AUSA) is a non- profit educational and professional development association serving America’s Army and supporters of a strong national defense. AUSA provides a voice for the Army, supports the Sol- dier and honors those who have served in order to advance the security of the nation.