Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mark Twain Facts

Name: Date: MARK TWAIN FACTS Directions: Read these facts about Mark Twain. Using the “Main Ideas and Supporting Details” handout, sift and sort them into categories. 1. Twain’s first famous story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” is a humorous story about a trick frog owned by a gold miner in California. 2. Mark Twain was the Vice-President of the American Anti-Imperialist League; he believed that the US should not limit the freedoms of people in other countries. 3. Many of Mark Twains’ younger characters are inspired by his life growing up in Missouri. 4. Mark Twain was known for wearing all white clothes. 5. His most famous novels include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which are stories about the adventures of two boys growing up in Missouri. 6. After failing as a gold miner in Nevada, Mark Twain got a job as a writer for the Territorial Enterprise where he developed material for many of his early writings. 7. Mark Twain’s novels A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court and The Gilded Age criticized politics in the US. 8. Early in his career, Mark Twain was considered a writer in the Sagebrush School, a group of writers in Nevada writing about the life of miners in the Gold Rush. 9. Throughout his life, Twain was concerned with making sure that young people had a chance to learn and grow up in a safe environment. In 1906, he founded The Angel Fish and Aquarium Club for girls. 10. -

Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut

MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS No. CT-359-A (Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF THE MEASURED DRAWINGS PHOTOGRAPHS Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 m HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS NO. CT-359-A Location: Rear of 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Hartford County, Connecticut. USGS Hartford North Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates; 18.691050.4626060. Present Owner. Occupant. Use: Mark Twain Memorial, the former residence of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), now a house museum. The carriage house is a mixed-use structure and contains museum offices, conference space, a staff kitchen, a staff library, and storage space. Significance: Completed in 1874, the Mark Twain Carriage House is a multi-purpose barn with a coachman's apartment designed by architects Edward Tuckerman Potter and Alfred H, Thorp as a companion structure to the residence for noted American author and humorist Samuel Clemens and his family. Its massive size and its generous accommodations for the coachman mark this structure as an unusual carriage house among those intended for a single family's use. The building has the wide overhanging eaves and half-timbering typical of the Chalet style popular in the late 19th century for cottages, carriage houses, and gatehouses. The carriage house apartment was -

Nina Clemens Gabrilowitsch, 55, Twain's Last Direct Heir, Dies

Nina Clemens Gabrilowitsch dies Home | Quotations | Newspaper Articles | Special Features | Links | Search The New York Times, January 19, 1966 Nina Clemens Gabrilowitsch, 55, Twain's Last Direct Heir, Dies LOS ANGELES, Jan. 18 (AP) - The county Coroner's office reported today that Miss Nina Clemens Gabrilowitsch, the last direct descendant of Mark Twain, had died Sunday. She was 55 years old. Miss Clemens was found dead in her room at a Los Angeles motel where she often stayed. Several bottles of pills and alcohol were found in the room, the police said. An autopsy was planned. A Los Angeles bartender said today that Miss Clemens had quipped to him on Saturday night: "When I die, I want artificial flowers, jitterbug music and a bottle of vodka at my grave." She was the granddaughter of Twain, whose real name was Samuel Langhorne Clemens. She preferred to use the writer's family name rather than her own. Miss Clemens, who was born four months after her grandfather died, once said that although she had never known him she knew his works "backwards and forwards." Miss Clemens was the daughter of Twain's daughter, Mrs. Clara Langhorne Clemens Samoussoud, and Clara's first husband, Ossip Gabrilowitsch. Mr. Gabrilowitsch was conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra from 1919 until his death in 1936. Miss Clemens's mother died in San Diego on Nov. 19, 1962. A family attorney, Al Matthews, said Miss Clemens had lived on the income of Twain's estate, which he estimated at about $2-million. He said Miss Clemens had an income of $1,500 a month after taxes. -

351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, CT 06105 Annual Report FYE 2015

The Mark Twain House & Museum 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, CT 06105! ! Annual Report FYE 2015 - February 1, 2014 through January 31, 2015! Report from Joel Freedman, President of the Board of Trustees To: Members, Friends, and Supporters of The Mark Twain House & Museum! January 31 marked the end of our fiscal year, as well as my first year as President of the Board of Trustees. It was a pivotal year with significant developments. ! We again raised over $2.5 million from our many individual, corporate, foundation, and government supporters. Due to our aggressive programming, which continues to expand our brand, we spent a bit more than raised, leaving us with a small deficit for the fiscal year. Our programming ranged from free community events, such as our annual Ice Cream Social, Tom Sawyer Day, and our popular “Trouble Begins” lectures, to celebrities such as Garrison Keillor and Ralph Nader. We also hosted Noam Chomsky and Ann Rice in larger area venues when demand outstripped our auditorium capacity. Lastly, we continued our marquee events at The Bushnell with best-selling author Dan Brown and our 4th annual “Mark My Words” event with Wicked author Gregory Maguire and Steven Schwartz, who created the Broadway musical. We increased revenue from admissions by 15% and are on track to meet our goal of 50% in three years. Our talented staff also added a popular Servants Tour to the other theme tours enabling guests to turn every visit into a new experience. The year also included many financial milestones. We made progress with our excellent corporate partner, Webster Bank, in renegotiating our debt from the construction of the Museum Center many years ago. -

The Social Consciousness of Mark Twain

THE SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS OF MARK TWAIN A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Social Sciences Morehead State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Rose W. Caudill December 1975 AP p~ ~ /THE ScS 9\t l\ (__ ~'1\AJ Accepted by the faculty of the School of Social Sciences, Morehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the Ma ster of Arts in Hist ory degree. Master ' s Commi ttee : (date TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • . • • . I Chapter I. FEMINISM . 1 II. MARK 1WAIN 1 S VIEWS ON RELIGION 25 III. IMPERIALISM 60 REFERENCES •••• 93 Introduction Mark Twain was one of America's great authors. Behind his mask of humor lay a serious view of life. His chief concern, . was man and how his role in society could be improved. Twain chose not to be a crusader, but his social consciousness in the areas of feminism, religion, and imperialism reveal him to be a crusader at heart. Closest to Twain's heart were his feminist philosophies. He extolled the ideal wife and mother. Women influenced him greatly·, and he romanticized them. Because of these feelings of tenderness and admiration for women, he became concerned about ·the myth of their natural inferiority. As years passed, Twain's feminist philosophies included a belief in the policital, economic, and social equality of the sexes. Maternity was regarded as a major social role during Twain's lifetime since it involved the natural biological role of women. The resu·lting stereotype that "a woman I s place is in the home" largely determined the ways in which women had to express themselves. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW APRIL 1965 ST. LOUIS LEVEE, 1871 The State Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1962-65 Roy D. WILLIAMS, Boonville, President L. E. MEADOR, Springfield, First Vice President LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville, Second Vice President LEWIS E. ATHERTON, Columbia, Third Vice President RUSSELL V. DYE, Liberty, Fourth Vice President WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg, Fifth Vice President JOHN A. WINKLER, Hannibal, Sixth Vice President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary Emeritus and Consultant RICHARD S. BROWNLEE, Columbia, Director, Secretary, and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society E. L. DALE, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau L. M. WHITE, Mexico GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1965 FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence ROBERT NAGEL JONES, St. Louis R. I. COLBORN, Paris GEORGE W. SOMERVILLE, Chillicothe VICTOR A. GIERKE, Louisiana WILLIAM C. TUCKER, Warrensburg Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1966 BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph LEO J. ROZIER, Perryville STANLEY J. GOODMAN, St. Louis W. WALLACE SMITH, Independence L. E. MEADOR, Springfield JACK STAPLETON, Stanberry JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston HENRY C. THOMPSON, Bonne Terre Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1967 WILLIAM AULL, III, Lexington *FRANK LUTHER MOTT, Columbia WILLIAM R. DENSLOW, Trenton GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis JAMES TODD, Moberly GEORGE FULLER GREEN, Kansas City T. -

Restoration of the Mark Twain House Is a Work in Progress Author

WINTER 1998 PAGE 3 Restoration of The Mark Twain Early Gifts to the House is a Work in Progress Campaign for The Mark Twain House Aid The task of restoring The Mark Twain Exterior Restoration House and Carriage House to their origi- nal appearance consists largely of attention Through the generosity of The Hartford to detail. Everyone involved, from the Foundation for Public Giving and the director and curator to the craftsmen and Hartford Courant Foundation, The fabricators, is committed to giving visitors Mark Twain House was able to begin the most accurate representation possible of the exterior restoration of both of our the way the buildings looked more than 100 nineteenth-century buildings in July. years ago when Samuel Clemens and his The Hartford Foundation for Public family occupied them. Here are some of the Giving's decision to award the museum a details that have been attended to in recent grant at its highest level of giving- months: $400,000—acknowledges the project's importance and crucial nature. The The exterior woodwork of the House Hartford Courant Foundation's $50,000 and Carriage House was thoroughly gift, one of that entity's largest grants, examined, and decisions were made as to recognizes that the museum's capital what could be repaired and what had to be projects represent well-thought-out replaced. Ihor Budzinsky, a master carpenter stewardship of this national treasure. from Kronenberger & Sons restoration firm, Capital Campaign Chairman David W. A newly completed fifth chimney rises on replicated the needed pieces in much the the north side of the House. -

Southern Ambivalence: the Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1984 Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris William R. Bell College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Bell, William R., "Southern Ambivalence: The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris" (1984). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625262. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mr8c-mx50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Southern Ambivalence: h The Relationship of Mark Twain and Joel Chandler Harris A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by William R. Bell 1984 ProQuest Number: 10626489 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10626489 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. -

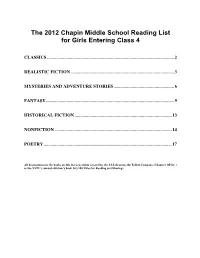

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4 CLASSICS ............................................................................................................... 2 REALISTIC FICTION .......................................................................................... 3 MYSTERIES AND ADVENTURE STORIES ..................................................... 6 FANTASY ................................................................................................................ 9 HISTORICAL FICTION ..................................................................................... 13 NONFICTION ...................................................................................................... 14 POETRY ................................................................................................................ 17 All descriptions for the books on this list were either created by the LS Librarian, the Follett Company (Chapin’s OPAC ) or the NYPL’s annual children’s book list (100 Titles for Reading and Sharing). Classics Aiken, Joan. Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Two young girls are sent to live on an isolated country estate where they find themselves in the clutches of an evil governess. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Follow the lives of four sisters in nineteenth-century New England. Baum, L. Frank. The Wizard Of Oz. An elegant and rich story about a girl, her friends, and a humbug wizard. Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. A young orphan named Mary is sent to live at a creepy English estate -

The Letters of Mark Twain, Complete by Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

The Letters Of Mark Twain, Complete By Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) 1 VOLUME I By Mark Twain MARK TWAIN'S LETTERS I. EARLY LETTERS, 1853. NEW YORK AND PHILADELPHIA We have no record of Mark Twain's earliest letters. Very likely they were soiled pencil notes, written to some school sweetheart --to "Becky Thatcher," perhaps--and tossed across at lucky moments, or otherwise, with happy or disastrous results. One of those smudgy, much-folded school notes of the Tom Sawyer period would be priceless to-day, and somewhere among forgotten keepsakes it may exist, but we shall not be likely to find it. No letter of his boyhood, no scrap of his earlier writing, has come to light except his penciled name, SAM CLEMENS, laboriously inscribed on the inside of a small worn purse that once held his meager, almost non-existent wealth. He became a printer's apprentice at twelve, but as he received no salary, the need of a purse could not have been urgent. He must have carried it pretty steadily, however, from its 2 appearance--as a kind of symbol of hope, maybe--a token of that Sellers-optimism which dominated his early life, and was never entirely subdued. No other writing of any kind has been preserved from Sam Clemens's boyhood, none from that period of his youth when he had served his apprenticeship and was a capable printer on his brother's paper, a contributor to it when occasion served. Letters and manuscripts of those days have vanished--even his contributions in printed form are unobtainable. -

Literary Destinations

LITERARY DESTINATIONS: MARK TWAIN’S HOUSES AND LITERARY TOURISM by C2009 Hilary Iris Lowe Submitted to the graduate degree program in American studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester _________________________________________ Dr. Susan K. Harris _________________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield _________________________________________ Dr. John Pultz _________________________________________ Dr. Susan Earle Date Defended 11/30/2009 2 The Dissertation Committee for Hilary Iris Lowe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Literary Destinations: Mark Twain’s Houses and Literary Tourism Committee: ____________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester, Chairperson Accepted 11/30/2009 3 Literary Destinations Americans are obsessed with houses—their own and everyone else’s. ~Dell Upton (1998) There is a trick about an American house that is like the deep-lying untranslatable idioms of a foreign language— a trick uncatchable by the stranger, a trick incommunicable and indescribable; and that elusive trick, that intangible something, whatever it is, is the something that gives the home look and the home feeling to an American house and makes it the most satisfying refuge yet invented by men—and women, mainly by women. ~Mark Twain (1892) 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 ABSTRACT 7 PREFACE 8 INTRODUCTION: 16 Literary Homes in the United -

The Persona of Mark Twain As Architect and Satirist of the Genteel Tradition

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2016 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2016 Into the Parlor: the Persona of Mark Twain as Architect and Satirist of the Genteel Tradition Morgan Ariel Oppenheimer Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016 Part of the American Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Oppenheimer, Morgan Ariel, "Into the Parlor: the Persona of Mark Twain as Architect and Satirist of the Genteel Tradition" (2016). Senior Projects Spring 2016. 346. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2016/346 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Into the Parlor: the Persona of Mark Twain as Architect and Satirist of the Genteel Tradition Senior Project submitted to The Division of Languages and Literature of Bard College by Morgan Oppenheimer Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2016 Acknowledgements I would like to start by thanking my mother, who read Huckleberry Finn to me, and my father, who has read almost everything I have ever written.