Nov 07 Website Layout.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Narbutaitė Onutė

Onutė Narbutaitė (b. 1956) learned the basics of composition from Bronius Kutavičius, studied composition with Julius Juzeliūnas at the Lithuanian State Conservatoire (now the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre), graduating in 1979. In 1997 the composer was awarded the Lithuanian National Arts and Culture Prize, the highest artistic distinction in Lithuania. She was awarded prizes at the competitions of the best music compositions of the year held by the Lithuanian Composers’ Union in 2004 and 2005 (Best Orchestral Work), in 2008 (Best Choral Work) and in 2015 (Composer of the Year). Her music was featured at the International Rostrum of Composers in 2004 (number one in the list of nine recommended works) and in 2010 (in the top ten list of best compositions). Onutė Narbutaitė’s works, a large number of which has been specially commissioned, have been performed at various festivals: Gaida (Vilnius), Vilnius Festival, Warsaw Autumn, Musica Viva (Munich), MaerzMusik (Berlin), Klangspuren (Schwaz), ISCM World Music Days (Bern and Vilnius), Icebreaker II: Baltic Voices (Seattle), Pan Music Festival (Seoul), Est-Ovest (Turin), Festival Onutė NARBUTaitė de Música (Alicante), Ars Musica (Brussels), Frau Musica Nova (Cologne), ArtGenda (Copenhagen), De Suite Muziekweek (Amsterdam), Schleswig- Holstein Music Festival (1992), Helsinki Festival WAS THERE (1992), Music Harvest (Odense), Czesław Miłosz Centennial Festival (Cracow), many other festivals and concerts in Europe, the USA, and A BUTTERFLY? Canada. Her music, as the featured composer, (2013) has been more widely presented at Aboa Musica (Turku), Kaustinen Chamber Music Week FOR STRING ORCHESTRA 20’30” (1998), Europäisches Musikfest Münsterland, the international summer arts school Synaxis Baltica ST. -

MTO 2.6: Broman, Report on the ISCM World Music Days

Volume 2, Number 6, September 1996 Copyright © 1996 Society for Music Theory Per F. Broman KEYWORDS: ISCM, Boulez, Pli selon Pli—Portrait de Mallarme, Erling Gulbrandsen, IRCAM, Georgina Born ABSTRACT: University of Copenhagen, Department of Musicology hosted a three-day series of lectures in conjunction with the ISCM World Music Days in Copenhagen 1996. The unifying thread running through all seminars was institutionalization of the avant-garde and the concept of pluralism. Of particular interest from a theoretical perspective was the presentation of Norwegian young scholar Erling Gulbrandsen’s recent doctoral dissertation on Boulez’s Pli selon Pli. [1] The ISCM World Music Days is an annual festival for contemporary music and this year’s event was held in Copenhagen, the 1996 Cultural Capital City of Europe, September 7–14. In conjunction with the festival, the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Musicology hosted a three-day series of lectures featuring Georgina Born (London): “Pierre Boulez’s IRCAM. Institution, History, and the Situation of Contemporary Music Today”; Erling Gulbrandsen (Oslo): “New Light on Pierre Boulez and Postwar Modernism”; Reinhard Oehlschlagel (Cologne): “Institutions of New Music: Development, Typology, Problems”; shorter papers were read by a panel including Per O. Broman (Uppsala), Erik Wallrup (Stockholm) Jens Hesselager (Copenhagen), Steen K. Nielsen (Aarhus), and Per F. Broman (Stockholm) and were followed by a discussion. This final session was chaired by Soren Moller Sorensen (Copenhagen). [2] Georgina Born’s presentation consisted of a brief review of her recent book Rationalizing Culture: IRCAM, Boulez, and the Institutionalization of the Musical Avantgarde (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), followed by a new, more elaborate discussion of the cultural policy for supporting composers—a topic hinted at in the final chapter of her book. -

Doctor of Musical Arts, Stanford University. Brian Ferneyhough, Adviser

Davíð Brynjar Franzson 65 North Moore Street, Apt. 6A New York, NY 10013 telephone: (+1) 650 248 5740 [email protected] http://franzson.com EDUCATION 2006 – Doctor of Musical Arts, Stanford University. Brian Ferneyhough, adviser. Mark Applebaum and Jonathan Berger, doctoral committee members. 2004 – Exchange studies in composition–– Columbia University. Tristan Murail, adviser. 2002 – Master of Arts in Music Composition, Stanford University. Mark Applebaum, adviser. Brian Ferneyhough, Melissa Hui, master committee members. 2001 – Diploma in Music Composition, with honors, Reykjavik College of Music. RECENT AWARDS, GRANTS AND SCHOLARSHIPS Artist residency at EMPAC, RPI, Troy, January 2013. First Prize, on Types and Typographies, loadbang, Call for Scores, 2012. Sixth month artist stipend, Listamannalaun, Reykjavik, 2012. Artist residency at the Watermill Center, Watermill, New York, Spring 2012. Artist residency at Schloss Solitude, 2011–2013. One of three finalists in the Christoph Delz composition competition, 2011. First prize for Il Dolce Far Niente at Eighth Blackbird's Music 09 competition. Stipendiumprize at the Darmstadt Internationalen Ferienkurse, 2008. Honorable Mention for il Dolce far Niente, Millennium Chamber Players Call for Scores, 2008. SELECTED COMMISSIONS AND PERFORMANCES Works commissioned by the Arditti Quartet, Elision Ensemble, the Christoph Delz Foundation, the Internationalen Ferienkurse Darmstadt, Yarn/Wire, Ensemble Adapter, Talea, Either Or, the Kenners, and loadbang among other. Performances by ensembles -

Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival Department of Music, University of Richmond

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Music Department Concert Programs Music 11-3-2017 Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival Department of Music, University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, University of Richmond, "Third Practice Electroacoustic Music Festival" (2017). Music Department Concert Programs. 505. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/all-music-programs/505 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Concert Programs by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LJ --w ...~ r~ S+ if! L Christopher Chandler Acting Director WELCOME to the 2017 Third festival presents works by students Practice Electroacoustic Music Festi from schools including the University val at the University of Richmond. The of Mary Washington, University of festival continues to present a wide Richmond, University of Virginia, variety of music with technology; this Virginia Commonwealth University, year's festival includes works for tra and Virginia Tech. ditional instruments, glass harmon Festivals are collaborative affairs ica, chin, pipa, laptop orchestra, fixed that draw on the hard work, assis media, live electronics, and motion tance, and commitment of many. sensors. We are delighted to present I would like to thank my students Eighth Blackbird as ensemble-in and colleagues in the Department residence and trumpeter Sam Wells of Music for their engagement, dedi as our featured guest artist. cation, and support; the staff of the Third Practice is dedicated not Modlin Center for the Arts for their only to the promotion and creation energy, time, and encouragement; of new electroacoustic music but and the Cultural Affairs Committee also to strengthening ties within and the Music Department for finan our community. -

Genevieve Lacey Recorder Genevieve Lacey Is a Recorder Virtuoso

Ancient and new! Traversing a thousand years of music for recorder, leading Australian performer Genevieve Lacey weaves together an enticing program of traditional tunes, baroque classics and newly composed music. Genevieve Lacey Recorder Genevieve Lacey is a recorder virtuoso. Her repertoire spans ten centuries, and she collaborates on projects as diverse as her medieval duo with Poul Høxbro, performances with the Black Arm Band, and her role in Barrie Kosky’s production of Liza Lim’s opera ‘The Navigator’. Genevieve has a substantial recording history with ABC Classics, and her newest album, ‘weaver of fictions’, was released in 2008. As a concerto soloist Genevieve has appeared with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Australian Brandenburg Orchestra, Academy of Ancient Music (UK), English Concert (UK), Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra and the Melbourne, West Australian, Tasmanian and Queensland Symphony Orchestras. Genevieve has performed at all the major Australian arts festivals and her European festival appearances have included the Proms, Klangboden Wien, Copenhagen Summer, Sablé, Montalbane, MaerzMusik, Europäisches Musikfest, Mitte Europa, Spitalfields, Cheltenham, Warwick, Lichfield and Huddersfield. Genevieve is strongly committed to contemporary music and collaborations on new works include those with composers Brett Dean, Erkki‐Sven Tuur, Moritz Eggert, Elena Kats‐ Chernin, James Ledger, John Rodgers, Damian Barbeler, Liza Lim, John Surman, Maurizio Pisati, Jason Yarde, Steve Adam, Max de Wardener, Bob Scott and Andrew Ford. As Artistic Director, Genevieve will direct the 2010 and 2012 Four Winds Festivals. In 2009, she will also design a composer mentorship/residency program for APRA‐AMCOS, and program a season of concerts for the 3MBS inaugural Musical Portraits series. -

ICMP Press Release

I C M P The International Confederation of Music Publishers European Office / Square de Meeûs 40 / Brussels / 1000 / Belgium ------------------- Database: music conferences worldwide 2020 (N.B.: non-exhaustive and rolling update) DATE EVENT LOCATION @ January SUPER MAGFEST Maryland, USA @MAGFest 02/01/20 – 05/01/20 07/01/20 – 10/01/20 CES 2020 Las Vegas, USA @CES 09/01/20 – 18/01/20 Winter Jazzfest NYC New York, USA @NYCWJF 10/01/20 – 14/01/20 APAP Conference New York, USA @APAP365 12/01/20 – 19/01/20 Jackson Indie Music Week Mississippi, USA @Jxnindiemusic 15/01/20 NYC Copyright and Technology Conference New York, USA @copyright4u 15/01/20 – 18/01/20 Eurosonic Noorderslag Groningen, The Netherlands @ESNSnl 16/01/20 – 17/01/20 NY:LON Conference New York, USA @NYLONConnect 16/01/20 – 18/01/20 Michigan Music Conference Michigan, USA @MichMusicConf 16/01/20 – 19/01/20 The 2019 NAMM Show Anaheim, USA @NAMM 21/01/20 – 23/01/20 NATPE Miami, USA @NATPE 22/01/20 – 25/01/20 MUSIC MOVES Mombasa, Kenya @MusicMovesIntl 22/01/20 – 26/01/20 Folk Alliance International Conference New Orleans, USA @folkalliance 24/01/20 – 27/01/20 January Music Meeting (JMM) Manitoba, Canada @manitobamusic ICMP – the global voice of music publishing DATE EVENT LOCATION @ 25/01/20 January Music Meeting (JMM) Toronto, Canada @SaugaMusic 28/01/20 – 30/01/20 AmericanaFest UK London, UK @AmericanaFest 28/01/20 – 01/03/20 transmediale Berlin, Germany @transmediale 29/01/20 – 31/01/20 ABO Annual Conference Cardiff, Wales @aborchestras 30/01/20 – 01/02/20 Trondheim Calling Trondheim, -

Impact Report 2019 Impact Report

2019 Impact Report 2019 Impact Report 1 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report “ Simone Young and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s outstanding interpretation captured its distinctive structure and imaginative folkloric atmosphere. The sumptuous string sonorities, evocative woodwind calls and polished brass chords highlighted the young Mahler’s distinctive orchestral sound-world.” The Australian, December 2019 Mahler’s Das klagende Lied with (L–R) Brett Weymark, Simone Young, Andrew Collis, Steve Davislim, Eleanor Lyons and Michaela Schuster. (Sydney Opera House, December 2019) Photo: Jay Patel Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report Table of Contents 2019 at a Glance 06 Critical Acclaim 08 Chair’s Report 10 CEO’s Report 12 2019 Artistic Highlights 14 The Orchestra 18 Farewelling David Robertson 20 Welcome, Simone Young 22 50 Fanfares 24 Sydney Symphony Orchestra Fellowship 28 Building Audiences for Orchestral Music 30 Serving Our State 34 Acknowledging Your Support 38 Business Performance 40 2019 Annual Fund Donors 42 Sponsor Salute 46 Sydney Symphony Under the Stars. (Parramatta Park, January 2019) Photo: Victor Frankowski 4 5 Sydney Symphony Orchestra 2019 Impact Report 2019 at a Glance 146 Schools participated in Sydney Symphony Orchestra education programs 33,000 Students and Teachers 19,700 engaged in Sydney Symphony Students 234 Orchestra education programs attended Sydney Symphony $19.5 performances Orchestra concerts 64% in Australia of revenue Million self-generated in box office revenue 3,100 Hours of livestream concerts -

World Music Days Slovenia 2015 26.9. – 1.10.2015

WORLD MUSIC DAYS SLOVENIA 2015 26.9. – 1.10.2015 CALL FOR WORKS REGULATION We kindly invite composers to submit scores, projects or installations. The ISCM World Music Days will take place in Slovenia from 26 September to 1 October 2015. According to the “Rules of Procedure for the Organisation of the ISCM World Music Days Festival”, submissions should be either official (by ISCM Members) or individual. Only one work per composer may be submitted for a given ISCM-WMD Festival, whether through official or individual submissions. An official submission by a Section or Full Associate Member will enjoy the exclusive right to the guaranteed performance of at least one submitted work at the ISCM-WMD Festival, providing the submission fulfils the following conditions: · the official submission should consist of exactly six works (as specified in the “Rules of Procedure for Membership Categories”); · preference will be given to shorter compositions, and to pieces composed after 2007. Categories: 1. Symphony orchestra (with or without choir, with or without soloist) (2+1.2+1.2+1.2+1.-4.3.3.1.- timp.perc4-pno-org-harp-strings) duration max. 20 min 2. String orchestra, 5.4.3.2.1 duration max. 15 min 3. Big band – Jazz orchestra 5.4.4.4 duration max. 8 min 4. Mixed choir 8.7.8.7 duration max. 8 min 5. Youth choir duration max. 8 min 6. Brass ensemble 6.4.4.1.2 duration max. 10 min 7. String Quartet duration max. 10 min 8. Wind Quintet duration max. 10 min 9. -

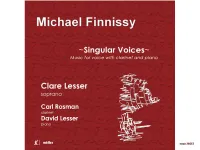

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices 1 Lord Melbourne †* 15:40 2 Song 1 5:29 3 Song 16 4:57 4 Song 11 * 3:02 5 Song 14 3:11 6 Same as We 7:42 7 Song 15 7:15 Beuk o’ Newcassel Sangs †* 8 I. Up the Raw, maw bonny 2:21 9 II. I thought to marry a parson 1:39 10 III. Buy broom buzzems 3:18 11 IV. A’ the neet ower an’ ower 1:55 12 V. As me an’ me marra was gannin’ ta wark 1:54 13 VI. There’s Quayside fer sailors 1:19 14 VII. It’s O but aw ken weel 3:17 Total Duration including pauses 63:05 Clare Lesser soprano David Lesser piano † Carl Rosman clarinet * Michael Finnissy – A Singular Voice by David Lesser The works recorded here present an overview of Michael Finnissy’s continuing engagement with the expressive and lyrical possibilities of the solo soprano voice over a period of more than 20 years. It also explores the different ways that the composer has sought to ‘open-up’ the multiple tradition/s of both solo unaccompanied song, with its universal connotations of different folk and spiritual practices, and the ‘classical’ duo of voice and piano by introducing the clarinet, supremely Romantic in its lyrical shadowing of, and counterpoints to, the voice in Song 11 (1969-71) and Lord Melbourne (1980), and in an altogether more abrasive, even aggressive, way in the microtonal keenings and rantings of the rarely used and notoriously awkward C clarinet in Beuk O’ Newcassel Sangs (1988). -

14 Contrib Notes 73-79

sembles Intercontemporain and Itinéraire of Paris, the Ensemble In all the difficulties of this world/Strength and peace, peace Aventure of Freiburg, the Nieuw Ensemble of Amsterdam, the ensemble to you Pro Musica Nipponia of Japan, the duo Aurele Nicolet, Robert Aitken These lyrics led to the composition of a preceding section and the Quintet of the Americas. His music has been performed at many comprised of a three-way conversation conceived by Lizo international events hosted by, among other organizations, the Centre Koni, a drama student at the University of Durban-Westville. Georges Pompidou, the ISCM World Music Days in Warsaw and Briefly, a man worries that his loved one, who is away, will not Mexico, the Helsinki Biennale, the Royal Festival Hall in London, the return to him, and he is made fun of by his friends for worry- Foro de Música Nueva in Mexico, the Societé de Musique ing too much. Finally, he realizes that they are right and that Contemporaine du Quebec and the Festival Latinoamericano de Música he is concerned over nothing. in Caracas. Luzuriaga received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1993. Mark Grimshaw studied music at Natal University, Durban, before completing his studies in Music Technology at York University, U.K. I WISH YOU STRENGTH AND INNER PEACE After 2 years in Italy, where he worked as a studio sound engineer, he Mark Grimshaw, School of Media Music & Performance, Uni- was appointed as a lecturer in the Music Department of the Univer- versity of Salford, Adelphi Campus, Peru St., Salford, M3 6EQ, sity of Salford, England, where he is currently head of Music Technol- United Kingdom. -

Liza Lim Olga Neuwirth Serge Prokofiev Orchestre Symphonique Du Swr Baden-Baden & Freiburg Kazushi Ono William Barton, Gunhild Ott, Håkan Hardenberger

LIZA LIM OLGA NEUWIRTH SERGE PROKOFIEV ORCHESTRE SYMPHONIQUE DU SWR BADEN-BADEN & FREIBURG KAZUSHI ONO WILLIAM BARTON, GUNHILD OTT, HÅKAN HARDENBERGER THÉÂTRE DU CHÂTELET O NOVEMBRE NMMP © David Young Liza Lim Souffles Olga Neuwirth Texte de Laurent Feneyrou Serge Prokofiev Ces œuvres nous racontent toutes trois une histoire, autour du souffle, de la trompe,desonembouchure,deslèvresquil’animentetdesimages,poétiques ou triomphantes, qu’elle évoque. Un égal souci de narration les traverse, em- Liza Lim pruntant à la tradition épique du symphonisme russe, ou au kalyuyuru du The Compass, désert australien – ce mot par lequel les aborigènes désignent le miroitement pour didgeridoo, flûte et orchestre de l’eau qui tombe sur des lits asséchés et la fluidité des chants entendus en rêve –, ou encore à un quotidien équivoque, hybride, menaçant, rendu à son Olga Neuwirth absurdité, tout en césures, proliférations et décalages impromptus. ...miramondo multiplo..., Endebrèvesscènesmusicales,suscitantbiendesimagesàl’écoute,...miramon- pour trompette et orchestre do multiplo... saisit toute l’hétérogénéité des résonances de la trompette, un instrument qu’Olga Neuwirth étudia dès sept ans. De la grandiloquence par- entracte foisvantardedesontimbreàl’orphéonauxéchosfelliniens,entrefiguresbaro- ques et autres lignes suaves, sorties de musiques de film, le vampirisme des ci- Serge Prokofiev tationsetleurmontagen’yexcluentnilatorsion,nilasalissureduson,nil’ironie, Sixième Symphonie, en mi bémol, ni même, en deçà, la douceur révolue des années d’enfance, -

CURRICULUM VITAE September 2018

CURRICULUM VITAE September 2018 Wolfgang von Schweinitz Wolfgang von Schweinitz was born on February 7, 1953 in Hamburg, Germany. After initial compositional attempts since 1960, he studied composition in 1968-1976 with Esther Ballou at the American University in Washington, D.C., with Ernst Gernot Klussmann and György Ligeti at the State Music Conservatory in Hamburg, and with John Chowning at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics in Stanford, California. Then he pursued his freelance composing work, living in Munich, Rome and Berlin, for twelve years in the countryside of Northern Germany and from 1993 to 2007 again in Berlin. In 1980 he lectured at the International Summer Courses for New Music in Darmstadt, and in 1994-1996 he was a guest professor at the Music Conservatory “Franz Liszt” in Weimar, Germany. He is currently based in Southern California, where he assumed James Tenney’s teaching position in September 2007 as a professor at the California Institute of the Arts. Since 1997, his compositions have been concerned with researching and establishing microtonal tuning and ensemble playing techniques based on non-tempered just intonation. Website: www.plainsound.org EDUCATION 1961 – 67 Private piano lessons 1965 Private music theory lessons with Christoph Weber, Hamburg 1968 – 69 Piano, music theory and composition lessons with Dr. Esther Ballou at the American University, Preparatory Division, Washington, D.C. 1970 Private counterpoint lessons with Prof. Ernst G. Klussmann, Hamburg 1971 High-school diploma at