Lakshmi Chand Jain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Unpaid Unclaimed Dividend for FY 2014-15.Xlsx

Pearl Global Industries Limited List ot unpaid/unclaimed dividend as on 07.01.2016 for FY 2014-15 Proposed Date of Amount Due Name Father/Husb Name Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Security Investment Type Transfer to IEPF (in Rs.) (DD-MON-YYYY) C/O V C VENKATRAMAN 303 SOMWAR Amount for unclaimed and A M RAJAPURKAR MANOHAR PETH PUNE 411011 INDIA Maharashtra 411011 PEAR0000000000001667 unpaid dividend 1498.50 19-Nov-2022 448 AMAR NIVAS SEVENTH CROSS SIXTH Amount for unclaimed and A N GOSWAMI SATISH CHANDRA MAIN MICO LAYOUT BANGALORE 560076 INDIA Karnataka 560076 PEAR0000000000000488 unpaid dividend 148.50 19-Nov-2022 NO 32 I B MAIN BINNY LAYOUT VIJAYA Amount for unclaimed and A R SRINIVASA PRASANNA RAMA CHANDRA RAO A NAGAR BANGALORE 560040 INDIA Karnataka 560040 PEAR0000000000001756 unpaid dividend 148.50 19-Nov-2022 14 AMAN E GULISTAN SOCY OPP MEMON HALL MAKTAMPURA SARKHEJ ROAD Amount for unclaimed and A RAZAK S MEMON SULEMAN U MEMON AHMEDABAD 380055 INDIA Gujarat 380055 PEAR0000000000000831 unpaid dividend 148.50 19-Nov-2022 BOHARA NURSING HOME BHUDHANA Amount for unclaimed and A S BOHARA K S BOHARA ROAD SHAMLI 247776 INDIA Uttar Pradesh 247776 PEAR0000000000001692 unpaid dividend 148.50 19-Nov-2022 Amount for unclaimed and A SARAVANABABU ARUNACHALAM DOOR NO.64, V.V.C.R LAYOUT, ERODE INDIA Tamil Nadu 638001 PEAR1202980000125331 unpaid dividend 22.50 19-Nov-2022 NO D-149 8TH CROSS ST MAHARAJA NAGAR Amount for unclaimed and A SUSAI MICHAEL S ARULAPPAN TIRUNELVELI INDIA Tamil Nadu 627011 PEARIN30039415886174 unpaid -

Subject Index

Economic and Political Weekly INDEX Vol XLV Nos 1-52 January-December 2010 Ed = Editorials MMR = Money Market Review F = Feature RA= Review Article CL = Civil Liberties SA = Special Article C = Commentary D = Discussion P = Perspectives SS = Special Statistics BR = Book Review LE = Letters to Editor SUBJECT INDEX ACADEMICIANS Who Cares for the Railways? (Ed) Social Science Writing in Marathi; Mahesh Issue no: 30, Jul 24-30, p.08 Gavaskar (C) Issue no: 36, Sep 04-10, p.22 Worker Deaths; Moushumi Basu and Asish Gupta (LE) ACADEMY Issue no: 37, Sep 11-17, p.5 Noor Mohammed Bhatt; Moushumi Basu and Asish Gupta (LE) ADDICTION Issue no: 52, Dec 25-31, p.5 A Case for Opium Dens; Vithal Rajan (LE) ACCIDENTAL DEATHS Issue no: 18, May 01-07, p.5 The Bhopal Catastrophe: Politics, Conspiracy and Betrayal; Colin ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS Gonsalves (P) K N Raj and the Delhi School; J Issue no: 26-27, Jun 26-Jul 09, p.68 Krishnamurty (F) Issue no: 11, Mar 13-19, p.67 Bhopal Gas Leak Case: Lost before the Trial; Sriram Panchu (C) ADOPTION LAW Issue no: 25, Jun 19-25, p.10 Expanding Adoption Rights (Ed) Issue no: 35, Aug 28-Sep 03, p.8 Chronic Denial of Justice (LE) Issue no: 24, Jun 12-18, p.07 AFGHANISTAN Exposure of War Crimes (Ed) Conspiracy to Implicate Maoists; Azad Issue no: 31, Jul 31-Aug 06, p.08 (LE) Issue no: 24, Jun 12-18, p.05 AGRARIAN REFORMS A Critical Review of Agrarian Reforms Gyaneshwari Express Sabotage - I; Asish in Sikkim; Anjan Chakrabarti (C) Gupta and Moushumi Basu (LE) Issue no: 05, Jan 30-Feb 05, p.23 Issue no: 23, Jun 05-11, p.04 -

Jan 2011.Qxd

JANUARY SPECIAL ISSUE VOL. 8 NO. 3 JANUARY 2011 www.civilsocietyonline.com `50 iiidddeeeaaasss FFFOOORRR TTTHHHeee NNNeeeWWW dddeeeCCCaaadddeee ARUNA RoY | m.S. SwAmINAthAN vIJAY mAhAJAN | ARUN mAIRA DILEEP RANJEkAR ChANDRASEkhAR hARIhARAN DARShAN ShANkAR | v. RAvIChANDAR vINAYAk ChAttERJEE Rob SINCLAIR & ANNUSkA PERkINS ‘to save tHe delHi garbage plan is trasH Pages 6-7 ganga tHink eco-systems’ farmers on organic mission P ages 10-11 Dhrubajyoti Ghosh talks of a landscape management plan to 10 ways to employ disabled Page 13 curb river pollution Page 9 anuja’s book is movie magic Pages 35-36 CONTENTs IDEAS FOR THE NEW DECADE Time to look within Rita and Umesh Anand . .16-17 READ U S. WE READ YO U. Citizens as auditors Aruna Roy . .18-19 Money can fly Vijay Mahajan . .20-21 Our monk and Transform capitalism Arun Maira . .21-22 other friends Seeds of the future s the decade ends with scams and scandals leaving their scars on our M.S. Swaminathan . .23 key institutions, there is a need to look within and think ahead. The amonk on the cover of this issue has been a companion for several Smarter govt schools years, appearing regularly in our cartoon on Page 5 and in our annual cal - endar. He has, in his funny way, inspired us to see the bigger picture. so Dileep Ranjekar . .24-25 have many individuals and groups across India, who, with their ideals and missions, live in the hope of building a modern, just and competitive Green equals hi-tech country. Chandrasekhar Hariharan . .26-27 some of them have, at our request for this special January issue, invest - ed time and effort in writing about what they consider to be important Plants for health and wealth ideas for the new decade. -

SRNO FOLIO NO NAME Shares As on March 31, 2017 1 0000019 K VISWANATHAN 20 2 0000231 BHARAT MULCHAND CHOKSEY 212 3 0000234 PRAN K

GOODYEAR INDIA LIMITED Registered Office: Mathura Road, Ballabgarh (Dist. Faridabad) - 121 004, Haryana, Corporate Office: 1st Floor, ABW Elegance Tower, Plot no. 8, Commercial Centre Jasola – 110 025, New Delhi, India CIN: L25111HR1961PLC008578 Email – [email protected],Website –www.goodyear.co.in Details of Shareholders and Equity Shares due for transfer to IEPF Suspense Account in respect of which Dividends have been unpaid/unclaimed since financial year ended December 31, 2008 Shares as on SRNO FOLIO_NO NAME March 31, 2017 1 0000019 K VISWANATHAN 20 2 0000231 BHARAT MULCHAND CHOKSEY 212 3 0000234 PRAN KRISHANA MUKHERJEE 20 4 0000258 ULLAL VARADARAJA NAYAK 64 5 0000271 SACHINDRA NATH BASU 578 6 0000490 RAJENDRA KISHORE BAIJAL 2 7 0000623 KUNDAN LAL KOHLI 318 8 0000702 JAGDISH PRASHAD PANNALAL AND CO PVT LTD 190 9 0000716 CLIVE STREET NOMINEES PVT LTD 176 10 0000750 MOTI LOKUMAL JHANGIANI 70 11 0000759 BANTVAL SIVA RAO 560 12 0000800 MOHINDRA NATH 145 13 0000829 MOHAN LAL LATH 36 14 0000916 AMAR KRISHNA PODDER 26 15 0001010 PRAPHULLA KUMAR SEN 286 16 0001059 SOHAN LAL BERRY 2 17 0001091 SITA BHAGAT 10 18 0001106 SATYA PAL 22 19 0001218 BABOO HAYATH SAHAB 140 20 0001260 JETHALAL GOKALDAS UDESHI 9 21 0001273 SURATH CHANDRA ROY 72 22 0001274 VIDYA PRAKASH SARNA 78 23 0001297 KISHORI LAL AGARWALA 56 24 0001319 NIHAL DEVI AHUJA 8 25 0001349 HIRA LAL ARORA 56 26 0001351 ROSHAN LAL ARORA 28 27 0001358 JANAK AWASTI 46 28 0001359 GULAMALI MOHMED BABVANI 18 29 0001369 NANAK CHAND RAI BAHADUR 144 30 0001454 SATHANALA BHULOKAMU -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

Nobel Prize - 2015

Nobel prize - 2015 ★ Physics - Takaaki Kajita, Arthur B. Mcdonald ★Chemistry - Tomas Lindahl, Paul L. Modrich, Aziz Sanskar ★Physiology or Medicine - William C. Campbell, Satoshi Omura, Tu Youyou ★Literature - Svetlana Alexievich (Belarus) ★Peace - Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet ★Economics - Angus Deaton Nobel prize - 2016 ★Physics - David J. Thouless, F. Duncan M. Haldane, J. Michael Kosterlitz ★Chemistry - Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J.Fraser Stoddart, Bernard L. Feringa ★Physiology or Medicine - Yoshinori Ohsumi ★Literature - Bob Dylan ★Peace - Juan Manuel Santos ★Economics - Oliver Hart, Bengt Holmstrom Nobel prize - History Year Honourable Subject Origin 1902 Ronald Ross Medicine Foreign citizen born in India 1907 Rudyard Kipling Literature Foreign citizen born in India 1913 Rabindranath Literature Citizen of India Tagore 1930 C.V. Raman Physics Citizen of India 1968 Har Gobind Medicine Foreign Citizen of Indian Khorana Origin 1979 Mother Teresa Peace Acquired Indian Citizenship 1983 Subrahmanyan Physics Indian-born American Chandrasekhar citizen 1998 Amartya Sen Economi Citizen of India c Sciences 2009 Venkatraman Chemistr Indian born American Ramakrishna y Citizen Booker Prize Year Author Title 2002 Yann Martel Life of Pi 2003 DBC Pierre Vernon God Little 2006 Kiran Desai The Inheritance of Loss 2008 Aravind Adiga The White Tiger 2009 Hilary Mantel Wolf hall 2010 Howard Jacobson The Finkler Question 2011 Julian Barnes The Sense of an Ending 2012 Hilary Mantel Bring Up the Bodies 2013 Eleanor Catton The Luminaries 2014 Richard Flanagan The Narrow Road to the Deep North 2015 Marlon James A Brief History of Seven Killings 2016 Han Kang, Deborah Smith The Vegetarian Booker Prize - Facts ★In 1993 on 25th anniversary it was decided to choose a Booker of Bookers Prize and the decision was done by a panel of three judges. -

Everest Kanto Cylinder Limited

Everest Kanto Cylinder Limited Unpaid Dividend Details for Final Dividend For The Year 2012-2013 10/03/2018 PAGE NO: 1 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NAMES & ADDRESS OF THE SHARE NO. OF Amount SR NO FOLIO NO. WARRANTNO. HOLDER SHARES (RS.) MICR NO ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 1203690000015751 1 VENKATA RAMANA REDDY 1000 200.00 108251 KOTTAPALLI 2 1201750200050677 2 DEELIP SHANTARAM MALPURE 25 5.00 100728 3 1201060100138321 3 VIJAY DADAJI WANDHARE 10 2.00 100729 4 1203280000098359 4 SIBY BAIJU . 10 2.00 100730 5 1201060001560863 9 GANESH KUMAR CHOUDHARY 25 5.00 100735 6 IN30177411142958 13 VIJEETA MALHOTRA 100 20.00 100739 7 1201910100235116 22 RAJESH KUMAR BANSAL 250 50.00 100751 8 IN30047642343949 26 M L VERMA 135 27.00 100755 9 IN30021411472260 27 SANDEEP SHARADKUMAR 20 4.00 100756 SHALIGRAM 10 IN30021410295877 32 DARSHANJIT KAUR DHUPIA 310 62.00 100761 11 1204470001026993 35 TAE HWAN LIM 300 60.00 100764 12 1203000000006260 36 JAI BHAGWAN 2750 550.00 100765 13 IN30021411618052 37 REKHA JOSHI 2 0.40 100766 14 1201910100771890 38 JITENDER MOHAN 1 0.20 100767 15 1204470003361033 40 RAVINDER JIT KAUR 50 10.00 100769 16 IN30094010256249 41 MANESH PRATAP SINGH 1450 290.00 100770 17 1201090004570991 42 KARISHMA BHALLA 50 10.00 100771 18 IN30133017718204 44 VINITA BAKSHI 500 100.00 100773 19 IN30167010293493 45 ARUNA PANT 50 10.00 100774 20 1204470001348619 48 UZMA NAYEEM 89 17.80 100777 -

Award and Prizes: July 2010

Award and Prizes: July 2010 Perelman rejects award After taking a three-month timeout, Russia's math whizz Grigori Perelman has finally turned down a $1,000,000 prize he won for having solved a century-old puzzle. The Clay Mathematics Institute (CMI) in March awarded its Millennium Prize of $1 million to the reclusive mathematician for proving the 106-year-old Poincaré conjecture, a theorem about the nature of multidimensional space. The eccentric Russian genius said the decision to give him the prize was unfair, as U.S. mathematician Richard Hamilton of Columbia University equally contributed to the proof. Dr. Perelman used a technique developed by Dr. Hamilton, to solve the Poincare conjecture. In 2006, Dr. Perelman refused to accept the Fields Medal, which is considered equal to the Nobel Prize . Sangeet Natak Akademi announces Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskars for 2009 The Sangeet Natak Akademi has announced the Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskars for 2009. These are awarded to artistes ³who have shown/demonstrated conspicuous talent in the fields of music, dance and drama.´ Young outstanding practitioners up to the age of 35 are eligible for the annual Puraskar. the following are the recipients of the Puraskar for 2009: Music:- Omkar Shrikant Dadarkar ± Hindustani vocal; Murad Ali ± Hindustani instrumental ± sarangi; Sanjeev Shankar and Ashwani Shankar (joint award) ± Hindustani instrumental ± shehnai; C.S. Sajeev ± Carnatic vocal; Mysore A. Chandan Kumar ± Carnatic instrumental ± flute; V. Balaji ± Carnatic instrumental ± mridangam; Anil Srinivasan ± creative and experimental music; and Moirangthem Meina Singh other major traditions of music ± Nata Sankirtana of Manipur. Dance:- Ragini Chander Shekar ± Bharatanatyam; Monisa Nayak ± Kathak; Hanglem Indu Devi ± Manipuri; Chinta Ravi Balakrishna ± Kuchipudi; Lingaraj Pradhan ± Odissi; Menaka P.P. -

1.Ashwini Ponnappa Is Associated with Which Sports? A) Sprint B) Boxing C) Badminton D) Discuss Throw

1.Ashwini Ponnappa is associated with which sports? a) Sprint b) Boxing c) Badminton d) Discuss throw Answer c) Badminton 2.Gudi Padwa is a festival celebrated by the people of a) Meghala b) West Bengal c) Assam d) Maharashtra Answer d) Maharashtra 3.The Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary is located in which state of India? a) Maharashtra b) Goa c) Gujarat d) Haryana Answer c) Gujarat .The ook The Ophaage of Wods has ee authoed by____. a) Adam Haslett b) Shinie Antony c) Sudeep Nagarkar d) Devdutt Pattanaik Answer b) Shinie Antony 5.What is the capital and currency of Lithuania? a) Accra, Cedi b) Vilnius, Litas c) Moscow, Ruble d) Tokyo, Yen Answerb) Vilnius, Litas .Asias lagest optical telescope ARIES was located in a) India b) Pakistan c) Bangladesh d) Nepal Answera) India 7.GST committee is headed by who among the following ? a) Srikrishna b) Arvind Subramanian c) Naresh Chandra d) Arun Jaitely Answer b) Arvind Subramanian 8.How much cash prize is awarded in Rajiv Gandhi Khel Ratna Award ? a) Rs.7.5 lakh b) Rs.6.5 lakh c) Rs.7 Lakh d) Rs.6 Lakh Answera) Rs.7.5 lakh 9.The scheme Kishore Vaigyanik Protsahan Yojana (KVPY) is funded by a) Ministry of Human Resource Development b) Ministry of Education, Youth and Information c) Department of Science and Technology d) Ministry of Finance Answer c) Department of Science and Technology 10.Lal Bahadur Shastri Stadium is situated in a) Maharashtra b) Gujarat c) Telangana d) Andhra Pradesh Answer c) Telangana .Naopa festial eleated i a) Himachal Pradesh b) J & K c) Haryana d) Chhattisgarh Answerb) J & K .Idias fist da-night Test was held in which stadium ? a) Feroz Shah Kotla Ground, New Delhi b) M.A. -

General Knowledge

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com General Knowledge – Part 20 INTERNATIONAL AGENCIES Asian Development Bank Abbreviation: ADB About:The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is a regional development bank to facilitate economic development in Asia. Headquarter: Mandaluyong, Metro Manila,Philippines Establishment: 19th December 1966. Head: Takehiko Nakao Motto: Fighting Poverty in Asia and Pacific. Membership:67 Countries. International Monetary Fund Abbreviation: IMF About: is an international organization which is working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world. Objective: to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world. Headquarter: Washington D.C., U.S. Establishment: 27th December 1945 MD and CEO: Christine Lagarde. Membership: 188 Countries. Official Language: English 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Association of Southeast Asian Nations Abbreviation: ASEAN About: It is a political and economic organisation of ten Southeast Asian countries. Objective: Its aims include accelerating economic growth, social progress, and sociocultural evolution among its members, protection of regional peace and stability, and opportunities for member countries to resolve differences peacefully. Headquarter: Jakarta, Indonesia Establishment: 8th August 1967. Secretary General: Lê L ng Minh Membership: 10 States, 2 Observers ươ Official Language: English. MOTTO: “One Vision, One Identity, One Community The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Abbreviation: OECD About: It is an international economic organisation. Objective:to stimulate economic progress and world trade. Headquarter: Paris, France. -

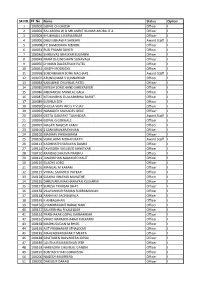

SR NO. PF No Name Status Option 1 100002 GOPAL CH GHOSH Officer

SR NO. PF No Name Status Option 1 100002 GOPAL CH GHOSH Officer I 2 100003 RAJ ARORA W O MR AMRIT KUMAR ARORA JT A Officer I 3 100004 SHUBHADA L KARMARKAR Officer I 4 100005 DHUNJISHAW R SARKARI Award Staff I 5 100008 P E DAMODARA MENON Officer I 6 100031 RUSI FRAMJI DAVER Officer I 7 100046 SHRINIVAS BHASKAR KULKARNI Officer I 8 100049 FRAM DHUNJISHAW SUNAVALA Officer I 9 100050 CHIMAN DALPATRAM PATEL Officer I 10 100052 JOSEPH RODRICKS Officer I 11 100068 SUBDHRABEN SONU NACHARE Award Staff I 12 100070 ARUNKUMAR V JUNNARKAR Officer I 13 100084 KANUBHAI CHUNILAL PATEL Officer I 14 100085 MITESH SOMCHAND SHREYASKER Officer I 15 100086 MEENAKSHI MANILAL GALA Officer I 16 100087 KESHAVBHAI DULLABHBHAI BAROT Officer I 17 100089 SUSHILA SEN Officer I 18 100090 SHEELA VIJAY WO S P VIJAY Officer I 19 100092 NAMADEV MAHADEV BIRJE Officer I 20 100093 GEETA GANAPAT TASHILDAR Award Staff I 21 100094 GOPAL G GOKHALE Officer I 22 100097 MALATI NAGESH KAMU Officer I 23 100101 S SANKARANARAYANAN Officer I 24 100102 MADHAV PARSHURAM Officer I 25 100106 VIJAYLAXMI MOHAN KATTI Award Staff I 26 100113 KASHINATH NARAYAN DAMLE Officer I 27 100114 RAVINDRA VASUDEO KANETKAR Officer I 28 100120 RAMDAS SANJIVA PRABHU Officer I 29 100121 JANARDHAN NAMADEO RAUT Officer I 30 100125 GLADYS LOBO Officer I 31 100126 MANILAL M KARANI Officer I 32 100127 VITHAL SAHADEO PATKAR Officer I 33 100128 SULBHA VINAYAK MARATHE Officer I 34 100135 DHRUVAKUMAR NARAYAN KULKARNI Officer I 35 100137 SURESH TRIMBAK BHAT Officer I 36 100138 VILAYANNUR RAMAN SUBRAMANIAN Officer I 37 -

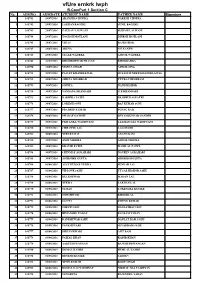

Vfure Ernkrk Lwph B.Compart 1 Section C No

vfUre ernkrk lwph B.ComPart 1 Section C No. ADMNO ADMDATE STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME Signature 1 161741 28/07/2016 AKANSHA CHOPRA NARESH CHOPRA 2 161742 29/07/2016 LAKHAN BAGHEL SUNIL BAGHEL 3 161743 29/07/2016 GAURAV LALWANI SURESH LALWANI 4 161744 29/07/2016 YOGESH MOTLANI DINESH MOTLANI 5 161745 29/07/2016 VIKAS RAJKISHOR 6 161747 29/07/2016 ARUNA NILKANTH 7 161748 29/07/2016 SAGAR WADERA ASHOK WADERA 8 161749 29/07/2016 KHOMESHWAR PRASAD KHORBAHRA 9 161750 29/07/2016 VISHAL SINGH ASHOK SING 10 161751 30/07/2016 PAWAN KHANDELWAL SHYAM SUNDER KHANDELAWAL 11 161752 30/07/2016 SHILPA MESHRAM YUVRAJ MESHRAM 12 161753 30/07/2016 SONIYA NAND KISHOR 13 161754 30/07/2016 VANDANA BHANDARI G R BHANDARI 14 161755 30/07/2016 RADHIKA PATEL PRABHUDAS PATEL 15 161756 30/07/2016 LOKESH SONI RAJ KUMAR SONI 16 161757 30/07/2016 PRADEEP KUMAR PUNAU RAM 17 161758 30/07/2016 BHARAT GANDHI SHYAMSUNDAR GANDHI 18 161759 30/07/2016 PRIYANKA WADHWANI LAXMAN DAS WADHWANI 19 161760 30/07/2016 CHHANNU LAL LALCHAND 20 161761 30/07/2016 NEELKAMAL ANAND RAM 21 161762 30/07/2016 AMIT MISHRA ASHOK MISHRA 22 161763 30/07/2016 BHAVIK PATEL MANILAL PATEL 23 161764 30/07/2016 CHINMAY AGRAHARI NAVEEN AGRAHARI 24 161765 30/07/2016 ABHISHEK GUPTA SIDDHESH GUPTA 25 161766 01/08/2016 AJAY KUMAR VERMA SUNDAR LAL 26 161767 01/08/2016 VIPLOVE SAHU YUGAL KISHOR SAHU 27 161768 01/08/2016 KULESHWAR MADAN LAL 28 161769 01/08/2016 NEEMA LAKHAN LAL 29 161770 01/08/2016 SUMAN LOKENDRA KUMAR 30 161771 02/08/2016 JITESHWARI KHOOBLAL 31 161772 02/08/2016 SALITA UMEND KUMAR 32 161773 02/08/2016