WO 2010/037714 Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.00 Overview of the Certification

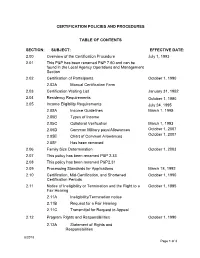

CERTIFICATION POLICIES AND PROCEDURES TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION: SUBJECT: EFFECTIVE DATE: 2.00 Overview of the Certification Procedure July 1, 1993 2.01 This P&P has been renamed P&P 7.60 and can be found in the Local Agency Operations and Management Section 2.02 Certification of Participants October 1, 1990 2.02A Manual Certification Form 2.03 Certification Waiting List January 31, 1992 2.04 Residency Requirements October 1, 1990 2.05 Income Eligibility Requirements July 24, 1995 2.05A Income Guidelines March 1, 1995 2.05B Types of Income 2.05C Collateral Verification March 1, 1993 2.05D Common Military pays/Allowances October 1, 2007 2.05E Chart of Common Allowances October 1, 2007 2.05F Has been removed 2.06 Family Size Determination October 1, 2003 2.07 This policy has been renamed P&P 2.33 2.08 This policy has been renamed P&P2.31 2.09 Processing Standards for Applications March 18, 1992 2.10 Certification, Mid-Certification, and Shortened October 1, 1990 Certification Periods 2.11 Notice of Ineligibility or Termination and the Right to a October 1, 1995 Fair Hearing 2.11A Ineligibility/Termination notice 2.11B Request for a Fair Hearing 2.11C Transmittal for Request to Appeal 2.12 Program Rights and Responsibilities October 1, 1990 2.12A Statement of Rights and Responsibilities 8/2018 Page 1 of 3 SECTION: SUBJECT: EFFECTIVE DATE: 2.13 Transferring Participants and the Use of the Verification October 1, 1995 of Certification Cards 2.13A Sample Verification of Certification 2.14 Eligibility of Aliens and Alien Students October 1, -

MICROCOMP Output File

S. HRG. 108–241, PT. 6 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 1050 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR FOR THE ARMED FORCES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 6 PERSONNEL MARCH 11, 19, 27, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:29 Aug 18, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 87328.CON SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004—Part 6 PERSONNEL VerDate 11-SEP-98 11:29 Aug 18, 2004 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 87328.CON SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 S. HRG. 108–241, PT. 6 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION ON S. 1050 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2004 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR FOR THE ARMED FORCES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 6 PERSONNEL MARCH 11, 19, 27, 2003 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–328 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

Study of Z-Disc-Associated Signaling Networks in Skeletal Muscle Cells by Functional and Global Phosphoproteomics

PHDTHESIS Study of Z-disc-associated Signaling Networks in Skeletal Muscle Cells by Functional and Global Phosphoproteomics Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Fakultät für Biologie der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg im Breisgau vorgelegt von Lena Reimann geboren in Bielefeld Freiburg im Breisgau 01.08.2016 Angefertigt am Institut für Biologie II AG Biochemie und Funktionelle Proteomforschung zellulärer Systeme unter der Leitung von Prof. Dr. Bettina Warscheid Dekan der Fakultät für Biologie: Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Driever Promotionsvorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Stefan Rotter Betreuer der Arbeit: Prof. Dr. Bettina Warscheid Referent: Prof. Dr. Bettina Warscheid Koreferent:Prof. Dr. Jörn Dengjel Drittprüfer: Prof. Dr. Gerald Radziwill Datum der mündlichen Prüfung:21.10.2016 ART IS I, science is we. - Claude Bernard Zusammenfassung Als essentielle, strukturgebende Komponente des Sarkomers spielt die Z-Scheibe eine maßge- liche Rolle für die Funktionalität der quergestreiften Muskulatur. Die stetige Identifizierung von neuen Z-Scheiben-lokalisierten Proteinen, sowie deren Relevanz in muskulären Krankheits- bildern, hat die Z-Scheibe zunehmend in den Fokus der aktuellen Forschung gerückt. Neben ihrer strukturgebenden Funktion zeigen neuere Studien, dass die Z-Scheibe ein Hotspot für Signalprozesse in Muskelzellen ist. Bisher gibt es jedoch keine globalen Untersuchungen zur Aufklärung der komplexen Signalwege assoziiert mit dieser Struktur. Um Z-Scheiben-assoziierte Signalprozesse näher zu charakterisieren, wurde im ersten Teil dieser Arbeit eine großangelegte Phosphoproteomstudie mit ausdifferenzierten, kon- trahierenden C2C12 Myotuben durchgeführt. Zu diesem Zweck wurden die tryptisch ver- dauten Proteine mittels SCX-Chromatographie fraktioniert. Die anschließende Phosphopep- tidanreicherung erfolgte mit Titandioxid, gefolgt von einer hochauflösenden massenspek- trometrischen Analyse. Insgesamt wurden 11.369 Phosphorylierungsstellen, darunter 586 in sarkomerischen Proteinen gefunden. -

Multi-Ancestry GWAS of the Electrocardiographic PR Interval Identifies 202 Loci Underlying Cardiac Conduction

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Multi-ancestry GWAS of the electrocardiographic PR interval identifies 202 loci underlying cardiac conduction. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/96q9k1d0 Journal Nature communications, 11(1) ISSN 2041-1723 Authors Ntalla, Ioanna Weng, Lu-Chen Cartwright, James H et al. Publication Date 2020-05-21 DOI 10.1038/s41467-020-15706-x Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15706-x OPEN Multi-ancestry GWAS of the electrocardiographic PR interval identifies 202 loci underlying cardiac conduction Ioanna Ntalla et al.# The electrocardiographic PR interval reflects atrioventricular conduction, and is associated with conduction abnormalities, pacemaker implantation, atrial fibrillation (AF), and cardio- 1234567890():,; vascular mortality. Here we report a multi-ancestry (N = 293,051) genome-wide association meta-analysis for the PR interval, discovering 202 loci of which 141 have not previously been reported. Variants at identified loci increase the percentage of heritability explained, from 33.5% to 62.6%. We observe enrichment for cardiac muscle developmental/contractile and cytoskeletal genes, highlighting key regulation processes for atrioventricular conduction. Additionally, 8 loci not previously reported harbor genes underlying inherited arrhythmic syndromes and/or cardiomyopathies suggesting a role for these genes in cardiovascular pathology in the general population. We show that polygenic predisposition to PR interval duration is an endophenotype for cardiovascular disease, including distal conduction disease, AF, and atrioventricular pre-excitation. These findings advance our understanding of the polygenic basis of cardiac conduction, and the genetic relationship between PR interval duration and cardiovascular disease. -

November 2017 Asbmb Today 1 President’S Message

CONTENTS NEWS FEATURES PERSPECTIVES 2 18 31 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE A MODEL IN THE WILD DUE DILIGENCE Keep your data safe 3 28 NEWS FROM THE HILL ANNUAL MEETING 32 Thinking about the future of funding How mentoring moments are made CAREER INSIGHTS Transitioning from science to science writing 4 18 MEMBER UPDATE The tiny mouse 34 lemur is one of RESEARCH SPOTLIGHT Madagascar’s most 7 abundant species Becoming a scientist-educator NEWS and a promising model for the Ph.D. student wins Tabor award study of human for long-distance factor work lung disease. 32 8 JOURNAL NEWS 8 The path of Parkinson’s proteins 28 9 New insights into bacterial toxins 10 Solo project on insulinlike growth factors 12 Obesity and cholesterol in teen boys 13 We shall know thine enemy, honey bee 14 From the journals 34 12 13 31 NOVEMBER 2017 ASBMB TODAY 1 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE MEMBER MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY It’s time for advocacy OFFICERS COUNCIL MEMBERS By Natalie Ahn Natalie Ahn Squire J. Booker President Victoria J. DeRose Wayne Fairbrother try to not be vexed by what’s in undermining his ability to concentrate Gerald Hart Rachel Green President Elect Blake Hill the news, but some days I just can- and be creative. Jennifer DuBois Susan Marqusee I not help myself. The White House The ASBMB takes a forceful stand Secretary Celia A. Shiffer decision to end the Deferred Action in this debate, with public statements Takita Felder Sumter Toni M. Antalis JoAnn Trejo for Childhood Arrivals program, or and visits to Congress by the Pub- Treasurer DACA, followed by a 70-point plan lic Affairs Advisory Committee, or ASBMB TODAY EDITORIAL for tightening immigration, was a PAAC, to explain the impact of hard- EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS ADVISORY BOARD worrying addition to an increasingly line immigration and DACA policies Jin Zhang Rajini Rao Wilfred van der Donk Chair nativist tone from our government on science. -

Multi-Ancestry GWAS of the Electrocardiographic PR Interval Identifies 210 Loci Underlying

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/712398; this version posted July 30, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Multi-ancestry GWAS of the electrocardiographic PR interval identifies 210 loci underlying 2 cardiac conduction 3 4 Ioanna Ntalla1*, Lu-Chen Weng2, 3*, James H. Cartwright1, Amelia Weber Hall2, 3, Gardar 5 Sveinbjornsson4, Nathan R. Tucker2, 3, Seung Hoan Choi3, Mark D. Chaffin3, Carolina Roselli3, 5 , 6 Michael R. Barnes1, 6, Borbala Mifsud1, 7, Helen R. Warren1, 6, Caroline Hayward8, Jonathan 7 Marten8, James J. Cranley1, Maria Pina Concas9, Paolo Gasparini9, 10, Thibaud Boutin8, Ivana 8 Kolcic11, Ozren Polasek11-13, Igor Rudan14, Nathalia M. Araujo15, Maria Fernanda Lima-Costa16, 9 Antonio Luiz P. Ribeiro17, Renan P. Souza15, Eduardo Tarazona-Santos15, Vilmantas Giedraitis18, 10 Erik Ingelsson19-22, Anubha Mahajan23, Andrew P. Morris23-25, Fabiola Del Greco M.26, Luisa 11 Foco26, Martin Gögele26, Andrew A. Hicks26, James P. Cook24, Lars Lind27, Cecilia M. Lindgren28- 12 30, Johan Sundström31, Christopher P. Nelson32, 33, Muhammad B. Riaz32, 33, Nilesh J. Samani32, 33, 13 Gianfranco Sinagra34, Sheila Ulivi9, Mika Kähönen35, 36, Pashupati P. Mishra37, 38, Nina 14 Mononen37, 38, Kjell Nikus39, 40, Mark J. Caulfield1, 6, Anna Dominiczak41, Sandosh 15 Padmanabhan41, 42, May E. Montasser43, 44, Jeff R. O'Connell43, 44, Kathleen Ryan43, 44, Alan R. 16 Shuldiner43, 44, Stefanie Aeschbacher45, David Conen45, 46, Lorenz Risch47-49, Sébastien Thériault46, 17 50, Nina Hutri-Kähönen51, 52, Terho Lehtimäki37, 38, Leo-Pekka Lyytikäinen37-39, Olli T. -

Genetic Susceptibility to Childhood Bronchiolitis

D 1461 OULU 2018 D 1461 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O. Box 8000 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA DMEDICA Anu Pasanen Anu Pasanen Anu University Lecturer Tuomo Glumoff GENETIC SUSCEPTIBILITY University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen TO CHILDHOOD Postdoctoral research fellow Sanna Taskila BRONCHIOLITIS Professor Olli Vuolteenaho University Lecturer Veli-Matti Ulvinen Planning Director Pertti Tikkanen Professor Jari Juga University Lecturer Anu Soikkeli Professor Olli Vuolteenaho UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF MEDICINE; Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala PEDEGO RESEARCH UNIT; MEDICAL RESEARCH CENTER OULU; ISBN 978-952-62-1898-4 (Paperback) OULU UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL ISBN 978-952-62-1899-1 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3221 (Print) ISSN 1796-2234 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS D Medica 1461 ANU PASANEN GENETIC SUSCEPTIBILITY TO CHILDHOOD BRONCHIOLITIS Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Health and Biosciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Auditorium F101 of the Faculty of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine (Aapistie 7), on 25 May 2018, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2018 Copyright © 2018 Acta Univ. Oul. D 1461, 2018 Supervised by Professor Mika Rämet Professor Mikko Hallman Doctor Minna Karjalainen Reviewed by Docent Liisa Myllykangas Professor Ville Peltola Opponent Professor Johanna Schleutker ISBN 978-952-62-1898-4 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-1899-1 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3221 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2234 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2018 Pasanen, Anu, Genetic susceptibility to childhood bronchiolitis. University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Medicine; PEDEGO Research Unit; Medical Research Center Oulu; Oulu University Hospital Acta Univ. -

Command Financial Specialist Training Student Manual

Command Financial Specialist Training Student Manual Marine & Family Programs – Resources Personal Financial Management Program Contents CHAPTER 1: Introduction to the Command Financial Specialist Training ..................................................................1.1 Purpose of the Training............................................................... 1.1 Overview of the Command Financial Specialist Training ............................. 1.2 Course Terminal Objectives .......................................................... 1.2 Financial Training Topics ............................................................ 1.2 CFS Task Areas ....................................................................... 1.3 Using of the Command Financial Specialist Student Manual .......................... 1.4 DAY ONE CHAPTER 2: Welcome and Administration .....................................2.1 Command Financial Specialist Data Card ............................................ 2.5 Command Financial Specialist Course Evaluation .................................... 2.7 Daily Homework ..................................................................... 2.9 CFS Course Agenda ................................................................. 2.10 Command Financial Specialist Pre/Post Test ......................................... 2.11 CHAPTER 3: The Need for PFM .....................................................3.1 Financial Problems and Concerns .................................................... 3.3 Financial Problems and Concerns ................................................... -

20 Anniversary Edition

1979 - 1999 20th Anniversary Edition TABLE of CONTENTS History of the Boom Operator Coin ........................................................................................................1 Differences in the Boom Operator Coins.................................................................................................2 Boom Operator Coin/Card Rules ............................................................................................................3 Altus AFB, OK.......................................................................................................................................4 97 OG.................................................................................................................................................4 54 ARS...............................................................................................................................................5 55 ARS...............................................................................................................................................8 Det 2.................................................................................................................................................10 FlightSafety Services Corporation.....................................................................................................11 Arlington, VA.......................................................................................................................................13 NGB/DOOM ....................................................................................................................................13 -

Die Rolle Des Herzspezifischen Proteins CEFIP in Der Kardialen Hypertrophie Und Kardiomyopathie

Molekulare Kardiologie Klinik für Innere Medizin III mit den Schwerpunkten Kardiologie, Angiologie und internistische Intensivmedizin Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel Direktor: Prof. Dr. med. Norbert Frey Die Rolle des herzspezifischen Proteins CEFIP in der kardialen Hypertrophie und Kardiomyopathie Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Franziska Dierck Kiel, 2018 Molekulare Kardiologie Klinik für Innere Medizin III mit den Schwerpunkten Kardiologie, Angiologie und internistische Intensivmedizin Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel Direktor: Prof. Dr. med. Norbert Frey Die Rolle des herzspezifischen Proteins CEFIP in der kardialen Hypertrophie und Kardiomyopathie Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel vorgelegt von Franziska Dierck Kiel, 2018 Erster Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Norbert Frey Zweiter Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Bernd Clement Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 10.07.2018 Zum Druck genehmigt:10.07.2018 gez.: (Dekanin) Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ..................................................................................................... 1 I Abbildungsverzeichnis ..................................................................................... 3 II Tabellenverzeichnis .......................................................................................... 5 -

Department of Defense Authorization for Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2011

S. HRG. 111–701, PT. 6 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 3454 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 6 PERSONNEL MARCH 10, 24; APRIL 28; MAY 12, 2010 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:14 Mar 16, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 Y:\BORAWSKI\DOCS\62159.TXT JUNE PsN: JUNEB DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011—Part 6 PERSONNEL VerDate Aug 31 2005 14:14 Mar 16, 2011 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 Y:\BORAWSKI\DOCS\62159.TXT JUNE PsN: JUNEB S. HRG. 111–701 PT. 6 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 3454 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2011 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 6 PERSONNEL MARCH 10, 24; APRIL 28; MAY 12, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ U.S. -

Annual Report 2018-19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Thiruvananthapuram Vithura, Thiruvananthapuram-695 551 Publication Committee Prof. M P Rajan Dr. Devaraj P Dr. Nishant K T Dr. Sukhendu Mandal Dr. Kumaragurubaran Somu Shri. Siva Dutt V K Shri. B V Ramesh Shri. Hariharakrishnan S Ms. Divya V J Ms. Sruthi U A Ms. Nimi Joseph Chaly Contact: 0471-2778044 Email : [email protected] Printed at Akshara offset Ph: 0471 2471174 Annual Report 2018-19 CONTENT Preface 1. Preamble ............................................................................................................................. 07 Introduction Board of Governors Finance Committee Building and Works Committee 2. Human Resources ............................................................................................................... 08 Faculty & Staff School of Biology School of Chemistry School of Mathematics School of Physics Emeritus/Honorary/Visiting/Adjunct Faculty Administrative and Support Personnel 3. Academic Programmes and Students ..................................................................................18 4. Research and Development Activities ................................................................................ 19 New Sponsored Projects Ongoing Sponsored Projects Completed Sponsored Projects 5. Research Publications ......................................................................................................... 34 Journal Articles Book Chapters 6. Awards and Honours ..........................................................................................................