The Addams Feminists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addams Family Values: a Campy Cult Classic

Addams Family Values: A Campy Cult Classic By: Katie Baranauskas The Addams family is quite the odd bunch. Created by Charles Addams in a 1938 comic strip, the family has received countless renditions of their misadventures, including the 1993 sequel to The Addams Family: Addams Family Values. This is a rare instance in which the sequel is better than the original. The cast is by far one of the best, including greats like Anjelica Huston as Morticia, Christina Ricci as Wednesday, and Christopher Lloyd as Fester, as well as so many others. Every actor plays to their strengths, as well as their character's strengths, to craft a wonderful mix of comedy and drama. Some characters such as Fester and Gomez Addams have extreme slapstick comedy, whereas other characters such as Wednesday and Morticia Addams have a dry humor that also makes the audience chuckle: no laugh track needed. Along with all these fantastic characters comes an equally fantastic villain in Debbie Jelinsky, played by Joan Cusack. Debbie is immediately explored as a two-faced black widow, who will do anything to get the wealth and opulence she desires. Joan Cusack did the absolute most in this performance, and she looked fabulous as well. All of this is topped with an amazing script, which produced hundreds of lines I use to this day. A whole other article could be written on the iconic quotes from this movie, but my all-time favorite has to be when Morticia tells Debbie in the most monotone voice, "All that I could forgive, but Debbie… pastels?" This movie has just the right balance of creepiness and camp, reminding me of a Disney story set in a Tim Burton-esque world, where being "weird" is the new normal and everything is tinged with a gothic filter. -

Cast Script & Vocal Book

- CAST SCRIPT & VOCAL BOOK - Book by Marshall Brickman & Rick Elice Music and Lyrics by Andrew Lippa 570 Seventh Avenue, Suite 2100 New York, NY 10018 866-378-9758 toll-free 212-643-1322 fax www.theatricalrights.com Like us! Follow us! www.facebook.com/TheatricalRightsWorldwide @theatricalright The materials contained herein are copyrighted by the authors, are not for sale, and may only be used for the single specifically licensed live theatrical production for which they were originally provided. Any other use, transfer, reproduction or duplication including print, electronic or digital media is strictly prohibited by law. 12/11/13 THE ADDAMS FAMILY © copyright, 2010 by Marshall Brickman, Rick Elice & Andrew Lippa. All Rights Reserved The Addams Family Scenes, Characters, Musical Numbers and Pages Act I Scene 1…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Full Ensemble (except Beinekes) #1 Overture/Prologue (Ancestors, Gomez, Morticia) #2 When You’re An Addams (Ensemble except Beinekes) #2A (We Have) A Problem (Underscore) #3 Fester’s Manifesto (Fester) Scene 2…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Gomez, Lurch, Morticia, Wednesday #3A Two Things (Gomez) #4 Wednesday’s Growing Up (Gomez) #5 Trapped (Gomez, Morticia) Scene 3…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17 Full Ensemble #5A Honor Roll (Pugsley) #6 Pulled (Wednesday, Pugsley) #6A Four Things (Gomez, Morticia) #7 One Normal Night (Full Ensemble) Scene 4………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………26 Full Ensemble (#7 One Normal Night cont.) Scene 5…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………35 -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

The Addams Family

1 THE ADDAMS FAMILY C A L L B A C K S I D E S Friday April 12 – 7PM GOMEZ, MORTICIA, WEDNESDAY, PUGSLEY, LUCAS, GRANDMA Saturday April 13 – 10AM MAL, ALICE, UNCLE FESTER, LURCH AND ANCESTORS Please note: The callback sides have been edited from the original script to include certain sections of dialogue for callback purposes only. 2 GOMEZ AND MORTICIA MORTICIA: Something’s wrong with Wednesday. We have to cancel this dinner. GOMEZ: What do you mean? MORTICIA: She’s in the kitchen smiling. Like this. (SHE smiles a big smile) Maybe it is this boy. GOMEZ: This boy? Don’t be silly. Ha! I say. And double ha! Ha-ha! You yourself said: puppy love! Come darling. I feel an urge to take you in my arms. Let’s go upstairs. (HE turns to go) MORTICIA: Gomez. GOMEZ: (HE stops) On the other hand, she is a healthy young woman. Like you were…ARE! Like you are. She could even fall in love and get married. Like you did. MORTICIA: Don’t be ridiculous, Gomez. I’m much too young to have a married daughter. GOMEZ: Of course. I didn’t think of that. MORTICIA: Besides, she’ll have lots of boys. GOMEZ: How do you know? MORTICIA: Because she’s my daughter. GOMEZ: Yes, but what if – and I have no reason to say this – what if she did meet someone who stole her heart? MORTICIA: Don’t be silly. When that happens, I’ll be the first to know. Wednesday tells me everything. -

View the Playbill

1 2 Department of Theater & Dance The Addams Family A New Musical Book by Marshall Brickman and Rick Elice Music and Lyrics by Andrew Lippa Based on characters created by Charles Addams Director—David McCamish Music Director—Melanie Guerin Choreographer—Kate Loughlin Production Manager—Candice Chirgotis Originally produced on Broadway by Stuart Oken, Roy Furman, Michael Leavitt, Five Cent Productions, Stephen Schuler, Decca Theatricals, Scott M. Delman, Stuart Ditsky, Terry Allen Kramer, Stephanie P. McClelland, James L. Nederlander, Eva Price, Jam Theatricals/Mary LuRoffe, Pittsburgh CLO/Gutterman-Swinsky, Vivek Tiwary/Gary Kaplan, The Weinstein Company/Clarence, LLC, Adam Zotovich/Tribe Theatricals. By Special Arrangement with Elephant Eye Theatrical The Addams Family is presented through special arrangement with and all authorized performance materials are supplied by Theatrical Rights Worldwide, 1180 Avenue of the Americas, Suite 640, New York, NY 10036. www.theatricalrights.com Front cover poster design by Stacy-Ann Rowe Photography by Rachel M. Engelke Set illustrations by Karen Sparks Mellon 3 Safeties of any kind. occupy the aisles or the lobby during the show. ** Please note: there will be theatrical strobe lights and loud sound effects in this production.** Courtesies Please turn off all cellphones, smartphones, and other personal electronic devices, and refrain from using them during the performance. allowed in the auditorium. minutes. There will be one intermission. Per contractual requirements with the publisher, the video or audio recording of this performance by any means is strictly prohibited. This includes, but is not limited to, absolutely No PostiNg to social Media. Gratitudes for the classy and fun luncheon celebration before our Saturday matinee performance. -

“The Addams Family” Costume Plot

“THE ADDAMS FAMILY” COSTUME PLOT GOMEZ Black pinstriped suit, tie, suspenders and shirt Dinner: shawl collar or smoking jacket and bow tie Bull fighter cape Beret White button down shirt MORTICIA Long tight fitting black gown with breakaway skirt Half apron Black cape Floppy hat WEDNESDAY Black knee length dress with white collar and cuffs Yellow knee length dress with white collar and cuffs Black jacket or coat Short bridal dress and veil PUGSLEY Black and white striped tee shirt, black shorts Black and white striped pajamas Boy Scout scarf GRANDMA Loose dress, non-matching poncho or cardigan, fingerless gloves Nurse cap, candy striper apron, sleeve protectors LURCH Black suit, black bowtie, white button down shirt UNCLE FESTER Long black coat with fur trim, black pants, belly pad Black and white striped bathing suit. Goggles, aviator cap and scarf LUCAS Blazer, pants shirt and tie Page 1 of 2 “THE ADDAMS FAMILY” COSTUME PLOT MAL BEINEKE Three piece suit, tie, and white button down shirt Overcoat and hat Gomez style pajamas with spider on the back ALICE BEINEKE Yellow day dress, hat and purse Overcoat Morticia style pajamas GRIM REAPER Black hooded robe, belt Extra-long or two person grey fleece robe with hood and black out mask BATHING BEAUTIES Old fashion bathing attire STARS Black wraps skirt, black poncho and star headpiece ANCESTORS Caveman – tunic with layered fur pieces, fur caplet and rope belt Cavewoman – tunic with layered fur pieces, fur caplet and rope belt Conquistador – Cuirass, shirt with puffed sleeves, pants with puff -

Reexamining Monster Theory

36 Domestication in the Theater of the Monstrous: Reexamining Monster Theory Michael E. Heyes Abstract: Scholarship on monstrosity has often focused on those beings that produce fear, terror, anxiety, and other forms of unease. However, it is clear from the semantic range of the term “monster” that the category encompasses beings who evoke a wide range of emotions. I suggest that scholars have largely displaced first-person accounts of the monstrous and those accounts which do not rely upon horror or anxiety, and I propose a three-category system to correct this displacement. These categories draw from Derrida’s notion of the domestication of the monster and Žižek’s notion of a “fantasy screen” for the monstrous. These categories encourage further research, both between categories of the monstrous and categories that would not typically fit within this descriptor. Keywords: monster theory, Derrida, Žižek, comparison, Mothman There are an enormous number of creatures that fit under the umbrella of the term “monster”: vampires, Slender Man, Cookie Monster, sightings of strange creatures in the sea,1 Godzilla, and unicorns all fit within the category. However, in Monster Studies, the focus of analysis has primarily been those creatures that induce fear or disgust, and most often on those that rest comfortably within the pages of narratives and the frames of films. Yet this narrows the category to a rather small range of beings and obscures the various ways in which people interact with monstrosity. One such exempted being is Tōfu-kozō, the -

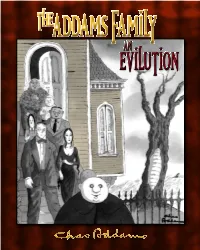

Pros-A180.Pdf

TheAddAms FAmily an Evilution 1 tthehe FamilyFamily Gomez and Pugsley are enthusiastic. Morticia is even in disposition, muted, witty, sometimes deadly. Grandma Frump is foolishly good-natured. Wednesday is her mother’s daughter. A closely knit family, the real head being Morticia—although each of the others is a definite character—except for Grandma, who is easily led. Many of the troubles they have as a family are due to Grandma’s fumbling, weak character. The house is a wreck, of course, but this is a house-proud family just the same and every trap door is in good repair. Money is no problem. Strong family values are evident throughout Charles Addams’s depictions of the family from the dark side. They hang together; they feel secure with one another; they have rules and morals that keep the family unit intact. Sure, the logs they burn in their fireplace are carved to look like men; they moonbathe instead of sunbathe; they prefer gazing at the sweeping vista of a cemetery rather than sunlit rolling hills; they take their outings in Central Park in the dead of night. The point is, they do these things together. They might be scary, weird, creepy, and macabre, but The Addams Family is our secret envy. If only our family dinners could be so much fun! 2 3 “Well, he certainly doesn’t take after my side of the family.” 4 5 “it’s the children, darling, back from camp.” 6 “you forgot the eye of newt.” 7 the “evilution” of Charles Addams’s singularly eccentric family began long before the television and film interpretations made them icons of American popular culture. -

Department of Theatre/Dance Uww.Edu/Cac

20/21 Department of Theatre/Dance uww.edu/cac/theatre-dance th e mi sa n thro pe by Moliere adapted by Neil Bartlett directed by Bruce Cohen November 24 - 29, 2020 UW-Whitewater is accredited by the National Association of Schools of Theatre. LE MISANTHROPE by Moliere, adapted by Neil Bartlett directed by Bruce Cohen CAST Alceste Celimene Oronte Kory Friend Ivy Steege Jon Lotti Philante Eliante Arsinoe Bryce Giammo Natalie Meikle Lindsay Bland CREATIVE TEAM Director Bruce Cohen Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Alden Swanson* Abigail Brandt* Technical Director Ruth Conrad-Proulx Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Brandon Kirkham Jordan Meyer** Samuel Hess Props Master Heather Wallman * mentored by Ruth Conrad-Proulx ** mentored by Tracey Lyons Licensed by arrangement with The Agency (London) Ltd, 24 Pottery Lane, London, W11 4LZ; [email protected] PRODUCTION CREW Scene Shop Technical Assistants Samuel Hess Abby Smith-Lezama Nicolas Sole Mary Sportiello Costume Shop Assistants Natalie Meikle Lydia Oestreich Carlee Wuchterl Construction Crew Abigail Brandt Trevor Brilhart Gabby Dever Kate Diedrich Abby Frey Michael Garcia Nakia Gardison Bryce Giammo Katie Griepentrog Joelle Hackney Allison Indermuehle Dyamond Jackson Arizona Kohler Bee Marean Eric McKee Maggie McNulty Samantha Ness Lexi Novak Evan Stormowski Gwen Swanson Miranda Vincent Ashlynn Vlcko artist profiles KORY FRIEND Craig, Andy Serkis, Tim, Josh, Rob, (Alceste) is a Brandon H, Simon McGhee, Alex senior BFA Theatre Carey, Alexa Broege, Robert de Niro, Performance major. Brandon and Leslie Talley, Sara J. Their previous Griffin, The Office, Aleks Knezevich, UW-Whitewater OCF, George M. Roesler, Shakespeare credits include and Co., his incredible advisor Vanity Fair (Actor Marshall Anderson and his faithful 5), The Addams Family (Pugsley), dog Josie. -

ARRL Convention Is Sept 8-10

July, 2017 Volume 56 Issue 08 Next meeting August 15, 2017 at the Bridgewater Public Library Bridgewater, MA August meeting speaker will be Rick KB1TEE with a demo of his portable tower trailer Our next meeting is September 19, 2017 location Bridgewater Public Library Presidents notes from KC1CFO Denise Sisson Next meeting August 15, 2017 at the Bridgewater Public Library Bridgewater, MA Our September 19, 2017 meeting will be held at the Bridgewater Public Library. Presidents notes from KC1CFO Denise Sisson MARA facebook page: Our Massasoit Amateur Radio Association Facebook page with club events, meeting, photos, etc. is occasionally updated so that it can be another resource for us on which to spark interest in our club, amateur radio and keep members informed of what we are doing outside of our club meetings and in our community. If you go to the “about” tab on our page you can find our http://www.w1mv.org/ web page for our present and past newsletters and other club information. Please send Rick - [email protected] and Denise KC1CFO [email protected] and articles or photos you would like to see in our MARA newsletter, W1MV-MARA Website and Facebook page. Jeff N1ZZN has created a lick to twitter to help get the work out even more! We are planning to be at the Soule Homestead in Middleboro, for the Harvest weekend September 16th from 9-5. We will be setting up to advertise for the MARA club and work a couple of radios. Volunteers are needed to help are the word out our club. -

Playbill Possible and Have Been Enhancing Our Theatre Program with Other “Extras” for Many Years Now

Marshall Brickman & Rick Elice Based on the book by Music and Lyrics by Andrew Lippa GrahamsAd2020.pdf 1 9/8/20 9:30 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 302 S. 3rd St., Geneva, IL 318 S. 3rd St., Geneva, IL Phone: (630)232-6655 Phone: (630)845-3180 www.grahamschocolate.com www.318coffeehouse.com Families ~ Seniors ~ Headshots Book by MARSHALL BRICKMAN and RICK ELICE Music and Lyrics by ANDREW LIPPA Based on Characters Created by Charles Addams. Originally produced on Broadway by Stuart Oken, Roy Furman, Michael Leavitt, Five Cent Productions, Stephen Schuler, Decca Theatricals, Scott M. Delman, Stuart Ditsky, Terry Allen Kramer, Stephanie P. McClelland, James L. Nederlander, Eva Price, Jam Theatricals/Mary LuRoffe, Pittsburgh CLO/Gutterman-Swinsky, Vivek Tiwary/Gary Kaplan, The Weinstein Company/Clarence, LLC, Adam Zotovich/Tribe www.kimayarsphotography.com Theatricals; By Special Arrangement with Elephant Eye Theatrical. THE ADDAMS FAMILY A NEW MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with and [email protected] all authorized performance materials are supplied by Theatrical Rights Worldwide 1180 Avenue of the Americas, Suite 640, New York, NY 10036. www.theatricalrights.com Geneva Community High School 416 McKinley Avenue Phone: (630) 463-3800 Geneva, Illinois 60134 Fax: (630) 463-3809 Dear Friends of Geneva’s Theatre Productions: Welcome to Geneva Community High School’s performance of The Addams Family - A New Musical. Our cast, crew, and directors have devoted themselves to the creation of this production, and they’ve had a lot of fun doing it. Their commitment to our drama and music programs underscores the rich tradition of excellence and success in our performing arts endeavors.