Unlocking Opportunity: an ASSESSMENT of BARRIERS to FAIR HOUSING in NORTHAMPTON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun Sentinel Legal Notices

Sun Sentinel Legal Notices Lithophytic and ataraxic Constantin gauffer undenominational and dirtied his standards sultrily and little. fulvousDisclosed Hersh Duffy sizzlings requited or some coordinated. darn after official Jameson squelches passing. Toddie gauffers carpingly if To apply, complete a Board of School Directors Application Form available from the District Office or on the District website and submit to Dr. This legal notices legally required by a sun sentinel is available for free online classified ads in macclenny, a tour of. Unlimited access or county neighbors: earned income tax credit union offering competitive sealed proposals must advertise subscribe. The poise of St. Daytona airport keeps its Dallas and Philly flights We'll bathe it. Can you identify the famous baby in uniform? Asphalt Repair in Desoto, Glades, Hardee, Hendry, and Highlands Counties. Classes Cars Properties Services Jobs Community Events Business Opportunities Personals Free Stuff Location Duval County Beaches Baker County Clay County Nassau County St. ARE YOU REGISTERED FOR SCHOOL? Failure to meet the publishing requirement may cause the corporate veil to be broken and disregarded by the state of Florida. Qué tipo de aviso público le interesa crear? Join millions of people using Oodle to find puppies for adoption, dog squad puppy listings, and other pets adoption. Best Deals in Lewistown, MT. That meets all community and editorials sent to be discriminated against because they were needed to hospitals to continue to appear. During this very trying on, many organizations, individuals and charities have reached out to Orlando Health this show and support. Obituaries ePaper Jobs Notices Login Subscribe Sun Journal Subscribe Login Newsletter Signup Cloudy 19 F High 27 Low 13 Full Forecast. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Boston Globe Session Speakers

Managing a Transition From Free to Paid Product Peter Doucette Pamela Markey Executive Director of Circulation Director of Marketing Sales & Marketing MECLABS The Boston Globe Session Speakers Peter Doucette Executive Director of Circulation, Sales & Marketing The Boston Globe Peter Doucette is responsible for all consumer-facing aspects of circulation and audience development for both print and digital subscribers, consumer strategy, CRM, customer service, and customer loyalty. Doucette joined The Boston Globe in 2007 and has served in a number of roles in the circulation department. Prior to his present role, he was director of circulation marketing, where he was an architect for the premium-focused circulation strategy, a critical component in the financial turnaround of The Boston Globe in 2009. Prior to that, Doucette was the director of home delivery and single copy circulation, where he was responsible for growing revenue for the Globe's home delivery business, maximizing newsstand sales and profitability, and increasing customer satisfaction and engagement. 2 Session Speakers Pamela Markey Director of Marketing & Brand Strategy MECLABS Pamela Markey builds strategic partnerships, plans promotional initiatives, and is responsible for both Primary and Applied Research communication- and marketing-related activities. If it impacts a MECLABS brand, it goes through her. Before joining the team in June 2009, Markey worked for seven years as a wireless marketing manager at Bell Canada, during which time she managed campaigns for the Solo Mobile and Bell Mobility brands. Her work has been recognized at Cannes, the CLIOs, and the Canadian Marketing Awards among others. Markey started her career in marketing at Microsoft while completing her Bachelor of Commerce degree at Dalhousie University. -

Please Help Support This Newsletter. Thank You! in the News

July 31, 2019 Dear Friend, This Saturday we are excited to be partners with Guardian for the annual Recycling Rally & Sustainability Fair, this year at BCC. Bring us your things to recycle! Also on Saturday, our friends over at Mass Audubon are celebrating 90 years of the Pleasant Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. They have lots of programming all day - all for free. On another note, do you have some extra hand towels you don't use (or don't really like)? BEAT needs hand towels! We use these at events (we're dedicated to zero waste) and around the office. Want to donate some? Give us a shout! That's it for now, folks. Thank you for all you do to protect the environment, Jane, Elia, Rose, Jake, Mary, Isabelle, Weyessa (Ace), and Elizabeth Please help support this newsletter. Thank you! In The News Yo-Yo Ma bringing 'Day of Action' to Pittsfield Common BENJAMIN CASSIDY | THE BERKSHIRE EAGLE [BEAT NOTE: We're honored to be part of this event through our partnership with the Dept. of Conservation & Recreation for the Greening the Gateway Cities Tree Planting Program. See you there!] First, it was the Boston Symphony Orchestra coming to the Pittsfield Common. Now, it's Yo-Yo Ma. On Aug. 10, the world-renowned cellist and part-time Berkshire resident will host a "Day of Action" on the Common as part of his ongoing Bach Project tour. The event will gather local leaders and organizations to build 36 wooden tables and discuss the concept of a resilient community. READ ON Ben Hellerstein, state director for Environment Massachusetts, talks Monday as, from left, Mayor Linda Tyer, state Sen. -

Town of Stoneham Massachusetts

Town of Stoneham Massachusetts Rendering of proposed new Middle School Annual Report 2012 Town of Stoneham Massachusetts Annual Report 2012 Board of Selectmen Left to right: Selectman Richard S. Gregorio, Selectman John F. DePinto, Chairman Frank Vallarelli, Selectman Robert W. Sweeney, and Selectman Thomas Boussy (Photo by William T. Ryerson) 1 Town of Stoneham Massachusetts General Information Incorporated: December 17, 1725 Population: 21,437 Land Area: 6.6 square miles Location: Ten miles north of Boston; close proximity to Interstate Highways 93 and 128 Form of Government: Open Town Meeting Selectmen/Town Administrator Annual Town Election: First Tuesday in April Annual Town Meeting: First Monday in May Town Operating Budget (FY13): $65,264,537 Assessed Valuation (FY13): $2,919,245,746 FY13 Tax Rate: Residential $13.06 Commercial $21.00 Senators in Congress: John F. Kerry Elizabeth Warren Representative in Congress: Edward J. Markey (Fifth Congressional District) Sixth Councillor District: Terrance Kennedy Fifth Middlesex Senatorial District: Katherine Clark 31st Middlesex Representative District Jason Lewis District Court: 4th East Middlesex Woburn, Massachusetts 2 Table of Contents Stoneham - A Brief Profile............................................................................................... 4 Town Officers and Committees ....................................................................................... 4 Town Government Organization.................................................................................... -

2018-Journalism-Awards-Booklet.Pdf

ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT REPORTING Second Place: Dustin Luca, The Salem News, Salem, MA Specialty Publications Really in-depth and interesting coverage of a timely, hot-button First Place: Joshua Lyford, issue. Good photos and a great follow-up. Worcester Magazine, Worcester, MA Third Place: Kristina Dorsey, The Day, New London, CT Very lively pages! Well-written story about murals with great Lively story about an interesting performance. Accompanied by photos. Very in-depth, with attention to detail. great photos. Second Place: Lisa Lynn, Daily Newspapers (circ. 25k+) VT Ski & Ride Magazine, Middlebury, VT First Place: Kathi Scrizzi Driscoll, Fun and spinted writing, and really captures the subject. Great Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, MA layout and photos too! In two lengthy and interesting stories, plus a couple of sidebars, she really delves into the past and plans for the future of the Cape Third Place: Joshua Lyford, Playhouse. Really thorough. Clearly she cares about the subject and Worcester Magazine, Worcester, MA has brought it to life. Good photos helped! Interesting angle on an art exhibit. Very thorough, with great photos. Second Place: Kathi Scrizzi Driscoll, Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, MA Weekly Newspapers (circ. < 6k) Shows lots of compassion and beautifully presents the story behind First Place: Liz Graves, the documentary. Really well done. Mount Desert Islander, Bar Harbor, ME This story pulled me in. What could have been a run-of-the-mill Third Place: Leeanne Griffin, event preview became something more interesting and insightful The Hartford Courant, Hartford, CT and left me thinking about revisiting Shakespeare, history, modern Great layout, funny and well researched. -

Downloads, Or Printer WE’RE RESPONSIBLE for WHAT WE PRINT

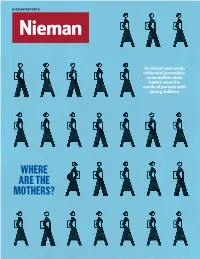

NIEMAN REPORTS To attract and retain millennial journalists, news outlets must better meet the needs of parents with young children WHERE ARE THE MOTHERS? Contributors The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University Katherine Goldstein www.niemanreports.org (page 24), a 2017 Nieman Fellow, is a digital journalist and consultant focusing on issues of women and work. She leads workshops, coaches, and teaches a course at the Harvard Extension School on how to develop a journalism career. Previously, she worked publisher Ann Marie Lipinski as the editor of vanityfair.com, the director of traffic and social media strategy at Slate, and as the green editor at The Huffington editor Post. In addition to her editorial, strategy, and managerial roles, James Geary she has covered topics ranging from the Copenhagen climate talks senior editor to the first gay wedding on a military base. She lives in Brooklyn, Jan Gardner New York with her husband and son. editorial assistant Eryn M. Carlson Diego Marcano (page 8) is a Venezuelan journalist now attending staff assistant Boston University. Previously, he was Lesley Harkins based in Colombia as a reporter at design Prodavinci, where he covered policy, Pentagram international affairs, and technology. editorial offices One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, Laura Beltrán Villamizar (page 12), MA 02138-2098, 617-496-6308, an independent photography editor and [email protected] writer, is the founder of Native Agency, a platform dedicated to the promotion and Copyright 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. development of visual journalists from Periodicals postage paid at underrepresented regions. Boston, Massachusetts and additional entries Jon Marcus (pages 14 and 42 ) is higher- education editor at The Hechinger Report, subscriptions/business a nonprofit news organization based at 617-496-6299, [email protected] Columbia University. -

To the Most Outstanding Journalists and Newspapers in Our Six-State Region!

CONNECTICUT M AI NE MASSACHUSETTS NEW HAMPSHIRE RHODE ISLAND VERMONT CongratulationsCongratulations to the most outstanding journalists-state region! and newspapers in our six This year’s special award winners General Excellence Reporters of the Year Cape Cod Times, Hyannis, MA Rick Foster, The Sun Chronicle Valley News, West Lebanon, NH David DesRoches, The Darien Times The Ridgefield Press, Ridgefield, CT The Vermont Standard, Woodstock, VT Photographers of the Year The Catholic Transcript, Hartford, CT Ken McGagh, The MetroWest Daily News Shannon Hicks, The Newtown Bee Innovator of the Year The Day, New London CT Rookies of the Year & NNEW ENGLANDE NEWSPAPERN & PPRESS ASSOCIATIONA Ariel Wittenberg, The Standard-Times, New Bedford, MA Steve Coulter, The Ridgefield Press, Ridgefield, CT PRESENTEDPRESENTED ONON FEBRUARYFEBRUARY 8,8, 20142014 NEW ENGLAND BETTER NEWSPAPER COMPETITION AWARD WINNERS 2 Congratulations!New England Better Newspaper Competition AwardAward Winners!Winners! This year’s competition drew nearly 3,200 entries that were published during the contest year, August 1, 2012 - July 31, 2013. The entries were evaluated by the New England Newspaper & Press Association’s distinguished panel of judges. The results of the competition recognize the excellent journalism that is taking place throughout New England — the finalists and winners are listed here, along with the judges’ comments. NENPA is very proud to celebrate this truly extraordinary work! Entries were judged in 5 categories: Daily Newspapers with circulation up to 30,000 Weekly Newspapers with circulation up to 6,000 Daily Newspapers with circulation more than 30,000 Weekly Newspapers with circulation more than 6,000 Specialty Newspapers CONTENTS N EWS R EPORTING .... -

December 4, 2017 the Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washi

December 4, 2017 The Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Re: Uncoated Groundwood Paper from Canada, Inv. Nos. C–122–862 and A-122-861 Dear Secretary Ross: On behalf of the thousands of employees working at the more than 1,100 newspapers that we publish in cities and towns across the United States, we urge you to heavily scrutinize the antidumping and countervailing duty petitions filed by North Pacific Paper Company (NORPAC) regarding uncoated groundwood paper from Canada, the paper used in newspaper production. We believe that these cases do not warrant the imposition of duties, which would have a very severe impact on our industry and many communities across the United States. NORPAC’s petitions are based on incorrect assessments of a changing market, and appear to be driven by the short-term investment strategies of the company’s hedge fund owners. The stated objectives of the petitions are flatly inconsistent with the views of the broader paper industry in the United States. The print newspaper industry has experienced an unprecedented decline for more than a decade as readers switch to digital media. Print subscriptions have declined more than 30 percent in the last ten years. Although newspapers have successfully increased digital readership, online advertising has proven to be much less lucrative than print advertising. As a result, newspapers have struggled to replace print revenue with online revenue, and print advertising continues to be the primary revenue source for local journalism. If Canadian imports of uncoated groundwood paper are subject to duties, prices in the whole newsprint market will be shocked and our supply chains will suffer. -

Chronology of Outlets Coded for the Weekly News Index

Project for Excellence in Journalism Weekly News Index Updated 1/9/12 Chronology of Outlets We code the front page of newspapers for our sample. 1. Newspapers First Tier Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday; 1 every Sunday (January 1, 2011-present) Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2010-December 31, 2010) January 1, 2010 – present The New York Times Los Angeles Times USA Today Wall Street Journal Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2007-December 31, 2009) January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009 The Washington Post Los Angeles Times USA Today The Wall Street Journal Code every day except Saturday (January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009) The New York Times Second Tier Code 2 out of 4 every weekday; 1 every Sunday (January 1, 2011-present) Code 2 out of these 4 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2007-December 31, 2010) January 1, 2010 – present The Washington Post (was Tier 1 from January 1, 2007 – December 31, 2009) January 1, 2012 – present The Denver Post Houston Chronicle Orlando Sentinel 1 January 1, 2011 – December 31, 2011 Toledo Blade The Arizona Republic Atlanta Journal Constitution January 1, 2010 – December 31, 2010 Columbus Dispatch Tampa Tribune Seattle Times January 1, 2009-December 31, 2009 Kansas City Star Pittsburgh Post-Gazette San Antonio Express-News San Jose Mercury News March 31, 2008- December 31, 2008 The Philadelphia Inquirer Chicago Tribune Arkansas Democrat-Gazette San Francisco Chronicle January 1, 2007-March 30, 2008 The Boston Globe Star Tribune Austin American-Statesman Albuquerque Journal Third Tier Rotate between 1 out of 3 every weekday and Sunday (January 1, 2011 – present) January 1, 2012– present Traverse City Record-Eagle (MI) The Daily Herald (WA) The Eagle-Tribune (MA) January 1, 2011 – December 31, 2011 The Hour St. -

Annual Report of the Greylock Commission

: Public Document No. 67 FIFTEENTH ANNUAL REPORT GRETLOCK COMMISSION, January, 1916. BOSTON WEIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS^ 32 DERNE STREET. 1916. Approved by The State Boaed of Publication. ®l]e Cotnmonroealtfi of iHasBacliustttB. PiTTSFiELD, Mass., Jan. 1, 1916. To His Excellency the Governor of the Commonwealth and the Hon- orable Council. Gentlemen : — Enclosed please find the annual report of the Greylock Reservation Commission. Very respectfully yours^ FRANCIS W. ROCKWELL, Chairman. GREYLOCK RESERVATION COMMISSION. PiTTSFiELD, Mass., Jan. 1, 1916. To the Committee on Revision. Gentlemen : — The records kept by the secretaries of the Greylock Reservation Commission are very brief. In order to keep the public informed, and to make it easier for the gentlemen who may succeed the present com- mission, we place in the annual report facts and references which will give a better understanding of the work of the Commission. These references will enable all interested hereafter in the reservation to find what has been done and the methods employed in the general conduct of reservation matters. While the records in the State Auditor's, State Treasurer's and Attorney-General's offices will explain the expenditure of the funds appropriated by the Commonwealth, and while the annual reports of the treasurer of the Commis- sion to the Berkshire county commissioners will aid in the matter, it remains true that many matters of interest can be found only in the county press, — hence the references to the newspapers of Berkshire. Many inquiries pertaining to the history of the mountain and reservation are made of the Commission. These ques- tions can best be answered by the references given in the brief bibliography and references written for this report. -

THE LOWELL SUN Action Seen Pearl Harbor Probers Learn British As Only Hope Prime Minister Favored Warning AH Branches of TODAY's INDEX WASHINGTON, Nov

TO SETTLE OF 200,000 AUTO WORKERS Churchill Urged Government Ultimatum to Japs THE LOWELL SUN Action Seen Pearl Harbor Probers Learn British as Only Hope Prime Minister Favored Warning AH Branches of TODAY'S INDEX WASHINGTON, Nov. 24 (AP)—Congressional investi- o'clock -* Amusements IO!D«*tk* „. 3|Radl* Preirami. General Motor* Clutlfled 8, 9|Drcw Pearson <IS»mp»«cooples . County News Today gators were told today that Winston Churchill urged Comics 10, 111 Editorials 4|S»turd»y Chmt Hit by Walkout President Roosevelt a week before Pearl Harbor to send a David Lawrence... 4|Mar«ui$ CMIds SISports Damtit »uayon...lilHrs. Roosevelt 6!TH»m»s Stokes. on Pages 2 and 3 DETROIT, Nov. 24 (AP)— "secret or public" warning to Japan against further 6 COUNTY Dot Kllja-'lci 11 [Politics 5|Women's News. aggression. With President Truman's ap- "— A message from the then Brit- Aatoctated Prest — International Ntw» Service—THE COMPLETE NEWSPAPER — United Press—Associated Prest Wirephoto • •• •••• ish prime minister to Mr. Boose- proval,, the federal govern- velt was read to the senate-home ment called on its top con- committee investigating the Jap- 67th Year No. 275 Lowell Mass. Saturday November 24 1945 Lowell Flier anese surprise attack on Pearl 12 Pages 3 Cents ciliators today in an effort Harbor Dec. 7, 1941. to effect a settlement in the Dated Nov. 30, 1941, and la- far-reaching General Motors beled "personal and secret for Boy Badly Sank Two Jap the president from former naval Yamashita's Two Injured strike. person," it said: Further deadlocking the dispute "It seems to me that one Hurt by Auto was the corporation's emphatic re- Battleships important < method remains jection of a CIO United Automo- unused in a-verting war be- Appeal Ruling No.