Church of Saint Lawrence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art & Architecture of the Basilica of Saint Lawrence

Chapel of Our Lady Exterior Rafael Guastavino The Art & Architecture of The style, chosen by the architect, is Guastavino (1842-1908) an architect and builder of To the left of the main altar is the Chapel of Our Lady. Spanish origin, emigrated to the United States from The white marble statue depicts Our Lady of the Spanish Renaissance. The central figure Barcelona in 1881. There he The Basilica of Assumption, patterned after the famous painting by on the main facade is that of our patron, had been a successful Murillo. Inserted in the upper part of the altar is a faience the 3"I century archdeacon, St. The Guastavino architect and builder, D.M. entitled The Crucifixion, which is attributed to an old Lawrence, holding in one hand a palm system represents a Saint Lawrence, renowned pottery in Capo di Monte, Italy. On either side designing large factories and unique architectural A Roman Catholic Church frond and in the other a gridiron, the homes for the industrialists of the tabernacle are niches containing statues of the treatment that has instrument of his torture. On the left of of the region of Catalan. He following: from the extreme left, Sts. Margaret, Lucia, given America some Cecilia, Catherine of Alexandria, Barbara, Agnes, Agatha, St. Lawrence is the first martyr, St. was also credited there with and Rose of Lima. Framing the base of the altar is a series Stephen, holding a stone, the method of being responsible for the of its most of tiles with some titles his martyrdom. He also holds a palm. -

Structural Assessment of the Guastavino Masonry Dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine

Structural Assessment of the Guastavino Masonry Dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine by Hussam Dugum Bachelor of Engineering in Civil Engineering and Applied Mechanics McGill University, Montreal, 2012 Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2013 c 2013 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of the Author: Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 10, 2013 Certified by: John A. Ochsendorf Professor of Building Technology and Civil and Environmental Engineering Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Heidi M. Nepf Chair, Departmental Committee for Graduate Students Structural Assessment of the Guastavino Masonry Dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine by Hussam Dugum Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 10, 2013 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering Abstract Historic masonry structures have survived many centuries so far, yet there is a need to better understand their history and structural safety. This thesis applies structural analysis techniques to assess the Guastavino masonry dome of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. This dome is incredibly thin with a L/t ratio of 200. Thus, it is important to assess this dome and its supporting arches, and confirm they are within adequate safety limits. This thesis gives an overview of the basic principles of masonry structural analysis methods, including equilibrium and elastic methods. Equilibrium methods are well suited to assess masonry structures as their stability is typically a matter of geometry and equilibrium rather than material strength. -

Descriptive Memory

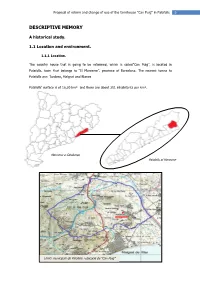

Proposal of reform and change of use of the farmhouse "Can Puig" in Palafolls 9 DESCRIPTIVE MEMORY A historical study. 1.1 Location and environment. 1.1.1 Location. The country house that is going to be reformed, which is called"Can Puig", is located in Palafolls, town that belongs to “El Maresme”, province of Barcelona. The nearest towns to Palafolls are: Tordera, Malgrat and Blanes Palafolls’ surface is of 16,20 km² and there are about 251 inhabitants per km². Maresme a Catalunya Palafolls al Maresme Límits municipals de Palafolls i ubicació de “Can Puig” 10 Proposal for reform and change of use of the house "Can Puig" in Palafolls FIXED AND LOCATION OF SITE Name of the farmhouse Can Puig The Building Typology Isolated Region Maresme Municipality Palafolls Geographical height 16 m above the sea level Seismicity Low City Limits Tordera limited to the north, to the North for spite, east to Blanes (I) to the North West Santa Susana County boundaries Bounded to the north by Valles to the Eastern Mediterranean by sea, by Barcelona to the South and West-east forest. 1.1.2 Geography Relief: Palafolls is located to the northeastern border in the Maresme region (Barcelona) by Tordera limit of frontier with the region of La Selva and while the province of Girona. The Municipal term is 3.16 km ², and it’s 16 m above the sea level.. The first of December of 2006 population was 8,102 inhabitants. The most popular occupation in Palafoll is teh tourism industry. The central core is called Ferreries and two of the main neirhborhoods are Sta. -

Art and Politics at the Neapolitan Court of Ferrante I, 1458-1494

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: KING OF THE RENAISSANCE: ART AND POLITICS AT THE NEAPOLITAN COURT OF FERRANTE I, 1458-1494 Nicole Riesenberger, Doctor of Philosophy, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Department of Art History and Archaeology In the second half of the fifteenth century, King Ferrante I of Naples (r. 1458-1494) dominated the political and cultural life of the Mediterranean world. His court was home to artists, writers, musicians, and ambassadors from England to Egypt and everywhere in between. Yet, despite its historical importance, Ferrante’s court has been neglected in the scholarship. This dissertation provides a long-overdue analysis of Ferrante’s artistic patronage and attempts to explicate the king’s specific role in the process of art production at the Neapolitan court, as well as the experiences of artists employed therein. By situating Ferrante and the material culture of his court within the broader discourse of Early Modern art history for the first time, my project broadens our understanding of the function of art in Early Modern Europe. I demonstrate that, contrary to traditional assumptions, King Ferrante was a sophisticated patron of the visual arts whose political circumstances and shifting alliances were the most influential factors contributing to his artistic patronage. Unlike his father, Alfonso the Magnanimous, whose court was dominated by artists and courtiers from Spain, France, and elsewhere, Ferrante differentiated himself as a truly Neapolitan king. Yet Ferrante’s court was by no means provincial. His residence, the Castel Nuovo in Naples, became the physical embodiment of his commercial and political network, revealing the accretion of local and foreign visual vocabularies that characterizes Neapolitan visual culture. -

Guastavino Structural Tile Vaulting in Pittsburgh Spring Semester 2021

The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute University of Pittsburgh, College of General Studies Guastavino Structural Tile Vaulting in Pittsburgh Spring Semester 2021 Instructor: Matthew Schlueb Program Format: Five week course, 90 minute academic lectures and guided tour, with time for questions. Course Objective: To offer a master level survey of the Pittsburgh architectural works by Rafael Guastavino and his son, drawn from their Catalan traditions in masonry vaulting, as interpreted by a practicing architect and author of architecture. Course Description: Architect Rafael Guastavino and his son Rafael Jr. emigrated to the United States in 1881, bringing the traditional construction method of structural tile vaulting from their Catalan homeland, thereby transforming the architectural landscape from Boston to San Francisco. This course will examine their works in Pittsburgh, illustrating the vaults and domes made with structural tiles, innovations in thin shell construction, fire-proofing, metal reinforcing, herringbone patterns, skylighting, acoustical and polychromatic tiles. Lectures supplemented with a guided tour of these local structures, provided logistics and health safety measures permit. Course Outline: Lecture 1: From Valencia to New York [Tuesday, March 16, 2021 3pm-4:30pm] Convent of Santo Domingo Refectory (arches and vaults; Mudéjar style; Zaragoza, Spain; 1283) Monastery of Santo Domingo Refectory (bóveda tabicadas / maó de pla; Juan Franch; Valencia, Spain; 1382) Batlló Textile Factory (vaulted arcade atop metal columns; Rafael Guastavino; Barcelona, Spain; 1868) La Massa Theater (shallow dome vault; Rafael Guastavino; Vilassar de Dalt, Spain; 1880) Boston Public Library (structural tile vaults; Charles McKim; Boston, Massachusetts; 1889-1895) St. Paul’s Chapel (dome; Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes; Columbia University, New York; 1907) Lecture 2: Material Innovations in Building Science [Tuesday, March 23, 2021 3pm-4:30pm] Cathedral of St. -

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO Inventiveness in 19Th Century Architecture by Jaume Rosell Colomina

RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO Inventiveness in 19th century architecture by Jaume Rosell Colomina This article was published in Catalan in pa. 494-522 by CAMARASA, Josep M.; ROCA, Antoni (dir.): Ciència i Tècnica als Països Catalans : una aproximació biogràfica (2v). Fundació Catalana per a la Recerca. Barcelona, 1995. The English version, revised by the author, was translated by Edward Krasny. An English version of this text was published in pp. 45-49 by TARRAGÓ, Salvador (editor): Guastavino Co. (1885-1962) : Catalogue of works in Catalonia and America. Col·legi d'Arquitectes de Catalunya. Barcelona, 2002. (ISBN 84-88258-65-8). Revised version, January 2010. Catalan and Spanish version in: https://upcommons.upc.edu/e-prints/browse?type=author&value=Rosell%2C+Jaume In memory of my father, Pere Rosell i Millach RAFAEL GUASTAVINO MORENO València, 1842 – Black Mountains, North Carolina, 1908 Key words: architecture, industrial architecture, cement, construction, cohesive construction, iron, brick, flat brick masonry, master builders, Modernisme, fire resistance, vaults. The contribution of Valencian Rafael Guastavino Moreno to Architecture was especially important in the technical area. He was the leading moderniser of an ancient building technique using flat brick masonry techniques, above all to erect vaults. Guastavino would later transfer these techniques from Catalonia to the United States of America, where he founded a family company that built, over two generations, more than one thousand buildings, many of them of great importance. These two accomplishments represent a notable contribution to contemporary Architecture: more so if we take into account a series of technological reflections and proposals that also constitute a contribution to the modernisation of construction, insofar as they entail an effort to understand the behaviour of and ways in which the new materials worked. -

Architectural Renovation Using Traditional Technologies, Local Materials and Artisan’S Labor in Catalonia

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIV-M-1-2020, 2020 HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, 9–12 September 2020, Valencia, Spain ARCHITECTURAL RENOVATION USING TRADITIONAL TECHNOLOGIES, LOCAL MATERIALS AND ARTISAN’S LABOR IN CATALONIA. O. Roselló 1, * 1 Architect Founder of www.bangolo.com and member co-founder of www.projectegreta.cat C.Pau Claris 154 Planta 4 Barcelona 08009 - [email protected] Commission II - WG II/8 KEY WORDS: Masia, Artisans, Vernacular, Architectural refurbish, Traditional technologies. ABSTRACT: The use of traditional techniques when restoring a masia is always the primary consideration in the preliminary phase of the project and during the site work. The virtues of traditional techniques compared to industrial production systems are described from multiple points of view: as a sustainable contemporary strategy, as generators of healthy spaces , as virtues of social and territorial scale, as a better formal contextualisation due to the limitations of pre-industrial materials. These are virtues that the industrial system has forgotten. The purpose of the Can Buch project (a masia in Northen Catalonia, Spain) was to restore the main house, some sheds and a barn, to enable rural ecotourism and to create a residence for the owner and future manager of the property. The promoter of the project intended to apply the values of permaculture. Maximising the use of Km0 materials from the start emphasised this intention. If we understand the traditional farmhouse as the site's resource map, applying this reality to the present work means recovering original representative principles. Currently, the project is in the last phase of works, but the results of applying this philosophy are already visible. -

Finite Element Modeling of Guastavino Tiled Arches

Transactions on the Built Environment vol 66, © 2003 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 Finite element modeling of Guastavino tiled arches E. P. Saliklis, S. J. Kurtz & S. V.Furnbach Dept. of Civil and Environmental. Engineering, Lafayette College, USA Abstract An investigation of Rafael Guastavino's arches has been conducted by means of finite element modeling and laboratory experimentation. A novel method of modeling laminated masonry tile construction via the finite element method has been devised. This technique takes advantage of the layered shell element features found in commercially available finite element programs. Historical Guastavino tiles have been tested to obtain material properties. These modem techniques have been employed in conjunction with Guastavino's original empirical design criteria to provide a better understanding of these historically significant structures. 1 Introduction Rafael Guastavino, born in 1842, emigrated to the United States to establish the Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company. The fascinating architectural legacy of Guastavino and his son (also Rafael Guastavino) has received scholarly attention [1],[2] but the mechanics of his designs have not garnered similar attention from structural engineers. The thin laminated tile construction that the elder Guastavino used in hundreds of structures in the Eastern United States had its roots in his native Catalan's indigenous vaulting badition. Before emigrating to the United States, Rafael Guastavino designed such laminated vaulting in Barcelona [3]. While it has been suggested that Guastavino came to the United States to utilize superior cements in his mortars [4], others claim it is more feasible to say that he emigrated because of his faith in the American construction industry and its ability to produce consistent and high quality materials [5]. -

Columbia University Visitors Center

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK Morningside Heights Self-Guided Walking Tour Welcome to Columbia University. Maps and other materials for self-guided tours are available in the Visitors Center, located in room 213 of Low Memorial Library. The Visitors Center is open 01 Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. A current Columbia I.D. is required to enter all buildings except Low Library and St. Paul’s Chapel unless accompanied by a University tour guide. A virtual tour and podcast are also available online. Columbia University was founded in 1754 as King's College by royal charter of King George II of England. It is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state of New York and the fifth oldest in the United States. Founded in 1754 as King's College, Columbia University is today an international center of scholarship, with a pioneering undergraduate curriculum and renowned graduate and professional programs. Among the earliest students and trustees of King's College were John Jay, the first chief justice of the United States; Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury; Gouverneur Morris, the author of the final draft of the U.S. Constitution; and Robert R. Livingston, a member of the five-man committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. After the American Revolution, the University reopened in 1784 with a new name—Columbia—that embodied the patriotic fervor that had inspired the nation's quest for independence. In 1897, the university moved from Forty-ninth Street and Madison Avenue, where it had stood for fifty years, to its present location on Morningside Heights at 116th Street and Broadway. -

Seismic Performance Assessment of Masonry Tile Domes Through Nonlinear Finite-Element Analysis

Seismic Performance Assessment of Masonry Tile Domes through Nonlinear Finite-Element Analysis S. Atamturktur, M.ASCE1; and B. Sevim2 Abstract: This article discusses a combined analytical and experimental study on the nonlinear seismic performance of two Guastavino-style masonry domes located in the United States. The seismic performance of these masonry domes is simulated with nonlinear finite-element (FE) models. To support the assumptions and decisions established during the development of the FE models, the vibration response of the domes is measured on-site and systematically compared against the numerical model predictions. Linear FE models are developed that are in close agreement with the measured natural frequencies and in visual agreement with the measured mode shapes. Next, these linear models are extended into the nonlinear range by incorporating the Drucker-Prager damage criterion. Finally, nonlinear FE models are used to assess the performance of these two domes under seismic loadings obtained from the 1940 El Centro earthquake acceleration records. The predicted displacements and internal tensile stress levels are used to make inferences about the potential behavior of these two buildings under the selected earthquake load. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0000243. © 2012 American Society of Civil Engineers. CE Database subject headings: Experimentation; Modal analysis; Finite element method; Nondestructive tests; Earthquakes; Masonry; Seismic effects. Author keywords: Experimental modal analysis; Nonlinear finite element analysis; Nondestructive testing; Earthquake performance; Masonry tile domes; Timbrel vaulting; Catalan vault. Introduction to ensure the structural safety of existing Guastavino tile domed and vaulted structures, particularly during extreme events such The inherent rigidity of the dome enabled early builders to achieve as earthquakes and high winds. -

Vertical Access

TECHNICAL VERTICAL TECHNICALPast Past Projects Projects and and Current Current Research Research on on Guastavino Guastavino Tile Ceilings,Ceilings, Domes Domes and and Vaults Vaults VERTICAL HIGHLIGHTACCESS HIGHLIGHT access P AST P ROJECTS P AST PUniversitatROJECTS Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona, Spain. B IBBILIOGRAB LIOGRAP HYP HY Kent coordinated the construction of a full-size Guastavino As part of our work inspecting and documenting historic s part of our work inspecting and documenting historic ThThee following following is a selectedis a selected bibliography bibliography of general of resourcesgeneral resourcesuseful in the buildings, Vertical Access (VA) has been involved with veral vaultbuildings, as part Vertical of a hands-on Access (VA) workshop has been for involved the APTI with annual studyuseful and inevaluation the study of and structures evaluation incorporating of structures Guastavino incorporating construc- projects investigating original Guastavino tile ceilings, vaults conference several projects held investigating in 2013. original Guastavino tile tionGuastavino systems: construction systems: and domes. Notable buildings constructed with Guastavino ceilings, vaults and domes. Notable buildings constructed ◗ ◗ Collins, George R. “The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting Kelly Streeter, a licensed structural engineer with VA, has Collins, George R. “The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting tile surveyed by VA in New York City include Cram and Awith Guastavino tile surveyed by VA in New York City include Cram fromfrom Spain Spain to toAmerica.” America.” Journal Journal of the of Societythe Society of Architectural of Architec - undertaken a testing and research program to define and Goodhue’s St. Thomas Church and Bertram Goodhue’s St.and Goodhue’s St. Thomas Church and Bertram Goodhue’s St. -

Past Projects and Current Research on Guastavino Tile Ceilings, Domes and Vaults ACCESS HIGHLIGHT

VERTICAL TECHNICAL Past Projects and Current Research on Guastavino Tile Ceilings, Domes and Vaults ACCESS HIGHLIGHT P AST P ROJECTS B I B LIOGRA P HY s part of our work inspecting and documenting historic The following is a selected bibliography of general resources useful in the buildings, Vertical Access (VA) has been involved with study and evaluation of structures incorporating Guastavino construc- several projects investigating original Guastavino tile tion systems: ceilings, vaults and domes. Notable buildings constructed ◗ Collins, George R. “The Transfer of Thin Masonry Vaulting Awith Guastavino tile surveyed by VA in New York City include Cram from Spain to America.” Journal of the Society of Architectural and Goodhue’s St. Thomas Church and Bertram Goodhue’s St. Historians 27 (October 1968): 176-201. Appendices I and II of Bartholomew’s Church, St. Paul’s Chapel at Columbia University, the article include further bibliographic references. Oyster Bar in Grand Central Terminal, the Battery Maritime Building ◗ The Guastavino Fireproof Construction Company/George and the Federal Reserve Bank. Outside of New York City, VA has Collins Architectural records and drawings. Drawings and performed survey work on All Saints Cathedral in Albany, NY, designed Archives. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia by Robert W. Gibson, and Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson’s Cadet University. Chapel at the United States Military Academy. In the fall of 2006, VA performed a comprehensive investigation of St. Francis de Sales Church ◗ Guastavino, Rafael. Essay on the Theory and History of Cohesive in Philadelphia, a Byzantine Revival structure designed by Henry D. Construction. Boston: Ticknor, 1892.