Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing the 2021 Class of Karen EDGE Fellows Emille Davie

Introducing the 2021 Class of Karen EDGE Fellows The EDGE Foundation is delighted to announce the 2021 Class of Karen EDGE Fellows. The Karen EDGE Fellowship Program was established with a generous gift from Karen Uhlenbeck on the occasion of her 2019 Abel Prize. The Fellowships are designed to support and enhance the research programs and collaborations of mid- career mathematicians who are members of an underrepresented minority group. The 2021 Fellows were selected on the basis of their excellent research programs and their plans to use the funds for enhancing those programs through collaboration and travel. The Karen EDGE Fellows for 2021 are Emille Davie Lawrence, University of San Francisco, and Manuel Rivera, Purdue University. Emille Davie Lawrence Manuel Rivera Emille Davie Lawrence received her Ph.D. in Mathematics from the University of Georgia in 2007, under the direction of Will Kazez and Clint McCrory. She was an undergraduate at Spelman College. She was a postdoctoral fellow at the Univer- sity of California, Santa Barbara, taught at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, and subsequently joined the faculty of University of San Francisco, where she has taught since 2011. She is currently Term Associate Professor and serves as Department Chair. Emille's research is in spatial graph theory, a branch of geometric topology in the intersection of knot theory and graph theory. Specifically, spatial graph theory is the study of embeddings of graphs in manifolds, with the manifold S3 being of particular interest. Her most recent research centers around classifying all groups which can occur as the topological symmetry group for some embedding of an abstract graph or family of graphs. -

Mathematics People

NEWS Mathematics People currently holds a Packard Fellowship and an NSF CAREER Wood Receives NSF grant. In high school, Wood won silver medals at the 1998 and 1999 International Mathematical Olympiad as the first Waterman Award US female in the competition. In 2001, she was awarded the Melanie Matchett Wood of Harvard Elizabeth Lowell Putnam Prize in the Putnam Mathemati- University has been named a co- cal Competition; in 2002 she became a Putnam Fellow. Her recipient of the 2021 National Science honors include the Alice T. Schafer Prize of the Association Foundation (NSF) Alan T. Waterman for Women in Mathematics (2002), the AMS–MAA–SIAM Award for “fundamental contribu- Morgan Prize (2003), a Clay Mathematics Institute Liftoff tions in number theory, algebraic Fellowship (2009), and the AWM–Microsoft Research Prize geometry, topology, and probability.” in Algebra and Number Theory (2018). She was named an She is the first woman mathemati- Inaugural Fellow of the AMS in 2012. cian to receive the honor. The Waterman Award annually recognizes an outstand- ing young researcher in any field of science or engineering Melanie Matchett The NSF statement reads in part: Wood “Throughout her scientific career, supported by NSF. Researchers forty years of age or younger, Wood has worked on some of the or up to ten years post-PhD, are eligible. Awardees receive most difficult problems in mathematics and has developed US$1 million distributed over five years. methods that combine ideas from across mathematics. Wood studies the statistical behavior of how factorization —Elaine Kehoe, from NSF and Harvard University announcements works in different systems of numbers, aiming to answer questions posed 200 years ago by Gauss.” Her work is aimed at understanding the distribution of number fields Akhtari Awarded and their fundamental structures, including class groups, p-class tower groups, and the Galois groups of their max- Michler Memorial Prize imal unramified extensions. -

2007-2008 Catalog Until the Catalog Expires (Six Years)

Oakland FINAL 5/3/07 4:22 PM Page 1 OAKLAND UNIVERSITY 2007–2008 UNDERGRADUATE CATALOG May 2007 Volume XLVII Published by Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan All data in this catalog reflect information as it was available at the publication date. Oakland University reserves the right to revise all announcements contained in this publication at its discretion and to make reasonable changes in requirements to improve or upgrade academic and non-academic programs. The academic requirements described in this catalog are in effect fall semester 2007 through summer session 2014. Undergraduate students admitted to a degree-granting program may use provisions in this catalog to meet requirements within that time frame. Oakland FINAL 5/3/07 4:22 PM Page 2 Oakland University is a legally autonomous state institution of higher learning. Legislation creating Oakland University as an independent institution, separate from Michigan State University, was established under Act No. 35, Public Acts of 1970. The university is governed by an eight member board of trustees appointed by the governor with the advice and consent of the Michigan Senate. As an equal opportunity and affirmative action institution, Oakland University is committed to compliance with federal and state laws prohibiting discrimination, including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Americans with Disabilities Act. It is the policy of Oakland University that there shall be no unlawful discrimination against any person on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, color, religion, creed, national origin or ancestry, age, height, weight, mar- ital status, handicap, familial status, veteran status or other prohibited factors in employment, admissions, educational programs or activities. -

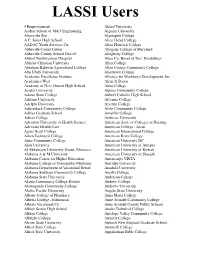

LASSI Users Master List

LASSI Users 4 Empowerment Alfred University Aarhus School of M&T Engineering Algoma University Above the Bar Algonquin College A.C. Jones High School Alice Lloyd College AADAC Youth Services Ctr Allan Hancock College Abbeville Career Center Allegany College of Maryland Abbeville County School Dist 60 Allegheny College Abbott Northwestern Hospital Allen Co. Board of Dev. Disabilities Abilene Christian University Allen College Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Allen County Community College Abu Dhabi University Allentown College Academic Excellence Institute Alliance for Workforce Development, Inc. Academics West Allyn & Bacon Academy of New Church High School Alma College Acadia University Alpena Community College Adams State College Althoff Catholic High School Addams University Alvernia College Adelphi University Alverno College Adirondack Community College Alvin Community College Adizes Graduate School Amarillo College Adrian College Ambrose University Adventist University of Health Science American Assn. of Colleges of Nursing Advocate Health Care American College - Arcus Agnes Scott College American International College Aiken Technical College American River College Aims Community College American University DC Ajou University American University of Antigua Al Akhawayn University, Ifrane, Morocco American University of Kuwait Alabama A & M University American University of Sharjah Alabama Center for Higher Education Americorps VISTA Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine Amridge University Alabama Department of Vocational Rehab -

November–December 2020

Newsletter VOLUME 50, NO. 6 • NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2020 PRESIDENT’S REPORT By now it is obvious that our old lives are not returning anytime soon. For a mathematician, being holed up alone can be a great opportunity for good research. But even for the most head-in-theorems mathematicians, the underlying stress of these times is wearing. According to the CDC 40% of Americans were struggling with mental health or substance abuse in June—two to three times higher than The purpose of the Association for Women in Mathematics is normal (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6932a1.htm). So you are not alone (well, you are socially distanced, but you know what I mean). I ask of you • to encourage women and girls to two things in this extraordinary time: give yourself permission to not be quite the study and to have active careers in the mathematical sciences, and superwomen you usually are, and give others a little extra slack, too. • to promote equal opportunity and Actually, I hope we can do both of these things now and in the future, the equal treatment of women and beyond pandemics, climate calamities, glaring racism, and deep political and social girls in the mathematical sciences. divides. It is hard to always get it right, so I hope we will assume the best of ourselves and of each other. That means understanding that people we love may do things we do not like, but we still love them. And it means when people we don’t know do something we find problematic, we should not assume they are bad people. -

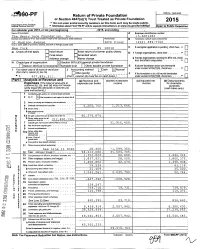

Form .790-PF 2015

OMB No 1545-0052 Form .790-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2015 Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury ► Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and Its separate instructions Is at www.trs.gov/form990pf. to Public Inspection For calendar year 2015, or tax year beginning , 2015 , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number Tho t-1 nrs, T.iii Pe-ii nntlatinn Tnr I 1 '3-Fi(1(11 7R7 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail Is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) 51 Madison Avenue 30th Floor ( 212 ) 489-7700 City or town, state or province , country , and ZIP or foreign postal code application Is pending , check here. New York NY 10 010 C If exemption ► LI G Check all that apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D I Foreign organizations , check here . ► Final return Amended return Address change Name change 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check q J here and attach computation . H Check type of organization : }{ Section 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation ► Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated q under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here . I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method Cash }( Accrual ► (from Part ll, column (c), line 16) FlOther (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 01. -

Murray Gell-Mann Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt687026tv No online items Finding Aid for the Murray Gell-Mann Papers 1931-2001, bulk 1955-1993 Processed by Charlotte E. Erwin, Loma Karklins, Kevin Knox, Nurit Lifshitz, and Elisa Piccio. Caltech Archives Archives California Institute of Technology 1200 East California Blvd. Mail Code 015A-74 Pasadena, CA 91125 Phone: (626) 395-2704 Fax: (626) 793-8756 Email: [email protected] URL: http://archives.caltech.edu/ ©2007 California Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Murray 10219-MS 1 Gell-Mann Papers 1931-2001, bulk 1955-1993 Descriptive Summary Title: Murray Gell-Mann Papers, Date (inclusive): 1931-2001, bulk 1955-1993 Collection number: 10219-MS Creator: Gell-Mann, Murray 1929- Extent: 54 linear feet Repository: California Institute of Technology. Caltech Archives Pasadena, California 91125 Abstract: The scientific and personal correspondence, organizational and government files, technical and teaching notes, writings and talks, civic and social action files, biographical and family papers, and a small collection of audiovisual material of Murray Gell-Mann (b. 1929) form the collection known as the Murray Gell-Mann Papers in the Archives of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Professor at Caltech beginning 1955, Gell-Mann won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1969 for his work on the theory of elementary particles. Gell-Mann is a founder of the Santa Fe Institute and writes on complex adaptive systems. He became emeritus from Caltech in 1993. Physical location: California Institute of Technology, Institute Archives Language of Material: Languages represented in the collection: English, Spanish, French Access The collection is open for research. -

CEOSE | Biennial Report to Congress

THE COMMITTEE ON EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES IN SCIENCE CEOSE AND ENGINEERING BIENNIAL REPORT TO CONGRESS 2017-2018 INVESTING IN DIVERSE COMMUNITY VOICES CEOSE MISSION & BACKGROUND The Committee on Equal Opportunities in Science and Engineering (CEOSE) advises the National Science Foundation (NSF) on policies and programs to encourage full participation by women, underrepresented minorities, and persons with disabilities within all levels of America’s science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) enterprise. The Committee on Equal Opportunities in Science and Engineering was established by the United States Congress through the Science and Engineering Equal Opportunities Act of 1980 to address the problems of growth and diversity in America’s STEM workforce. The legislation specifically provides that: There is established within the National Science Foundation a Committee on Equal Opportunities in Science and Engineering (hereinafter referred to as the “Committee”). The Committee shall provide advice to the Foundation concerning (1) the implementation of the provisions of sections 1885 and 1885d of this title and (2) other policies and activities of the Foundation to encourage full participation of women, minorities, and persons with disabilities in scientific, engineering, and professional fields [42 U.S.C.§1885(c)]. Every two years, the Committee shall prepare and transmit to the Director (of the Foundation) a report on its activities during the previous two years and proposed activities for the next two years. The Director shall transmit to Congress the report, unaltered, together with such comments as the Director deems appropriate [42U.S.C. §1885(e)]. The CEOSE is composed of between 12 and 16 individuals from diverse STEM disciplines, drawn from diverse institutions in higher education, industry, government, and the non-profit sectors. -

Candidate Biographies

Election Special Section FROM THE AMS SECRETARY Candidate Biographies Biographical information about the candidates has been supplied and verified by the candidates. Candidates have had the opportunity to make a statement of not more than 200 words on any subject matter with- out restriction and to list up to five of their research papers. Candidates have had the opportunity to supply a photograph to accompany their biographical information. Acronyms: AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science); AMS (American Mathematical Society); ASA (American Statistical Association); AWM (Association for Women in Mathematics); CBMS (Conference Board of the Mathematical Sciences); IAS (Institute for Advanced Study); ICM (International Congress of Mathematicians); IMA (Institute for Mathematics and Its Applications); IMU (International Mathematical Union); IPAM (Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics); LMS (London Mathematical Society); MAA (Mathematical Association of America); MSRI (Mathematical Sciences Research Institute); NAS (National Academy of Sciences); NRC (National Research Council); NSF (National Science Foundation); PIMS (Pacific Institute for the Mathematical Sciences); SIAM (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics); STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). President tional Committee for Mathematics, 2005–2008; Institute Ruth Charney for Advanced Study Program for Women, Advisory Board, Theodore and Evelyn Berenson Pro- 2007–2010; President of the AWM, 2013–2015; External fessor of Mathematics, Brandeis Uni- Review Committee, Banff International Research Station, versity. 2015; AWM Scientific Advisory Committee, 2015–2016; PhD: Princeton University, 1977. Centre de Recherches Mathématiques, Scientific Advisory AMS Offices: Member at large, 1992– Board, 2016–present. Fellow of the AMS, 2012; Fellow of 1995; Vice President, 2006–2009; the AWM, 2017. Member: AMS, AWM, MAA, SIAM. -

Fall Issue of the NAM Newsletter, fill Your Heart with Stories of the Devoted Work of the NAM Sincerely, Dr

1 Volume XLIX Number 3 The National Association of Mathematicians (NAM) publishes the NAM Newsletter four times per year. Editor workforce of mathematical scientists. Dr. Omayra Ortega (Sonoma State University) [email protected] NAM’s National Office: Dr. Leon Woodson, Executive www.omayraortega.com/ Secretary, Department of Mathematics, Morgan State Uni- versity, 1700 E Cold Spring Lane, Baltimore, MD 21251; Editorial Board e-mail: [email protected]. Dr. Mohammad K. Azarian (University of Evansville) [email protected] Subscription and membership questions should be di- http://faculty.evansville.edu/ma3/ rected to Dr. Roselyn E. Williams, Secretary-Treasurer, National Association of Mathematicians, P.O. Box 5766, Dr. Abba Gumel (Arizona State University) Tallahassee, Florida 32314-5766; (850) 412-5236; e-mail: [email protected] [email protected]. https://math.la.asu.edu/~gumel NAM’s Official Webpage: http://www.nam-math.org NAM’s History and Goals: The National Association of Mathematicians, Inc. (known as NAM) was founded Newsletter Website: The NAM website has a list in 1969. NAM, a nonprofit professional organization, has of employment as well as summer opportunities on the always had as its main objectives, the promotion of excel- Advertisements page. It also features past editions of the lence in the mathematical sciences and the promotion and Newsletter on the Archives page. mathematical development of under-represented minority mathematicians and mathematics students. It also aims to Letters to the editor and articles should be addressed address the issue of the serious shortage of minorities in the to Dr. Omayra Ortega via e-mail to [email protected]. -

Muddmath Newsletter

MUDDMATH VOLUME 14 = 2020 MUDDMATH | 2020 1 Letter From the Chair Dear Math Alumni, Families and Friends, I write at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has upended majors Forest Kobayashi ’20 and Savana Ammons ’20 our world, our beloved campus is nearly empty, and we each receiving a National Science Foundation Graduate meet each other mostly over Zoom. Had I written this Fellowship offer and math major Aria Beaupre ’21 letter in February, I would have been downright jubilant receiving a Goldwater Scholarship. about the incredible year our department was having. It is both humbling and thrilling to work in a At the top of my excitement would be the fact that we hired department with such amazing colleagues. As chair, three amazing new colleagues to join our department as my principal goal is to support our students, staff and assistant professors: Jamie Haddock (mathematical data faculty attain excellence in their teaching, learning and science), Haydee Lindo (commutative algebra) and Heather scholarship. Thanks to the generosity of several donors, Zinn-Brooks (nonlinear systems). One of these positions, including two gifts just last year to support research and at long last, is a growth position to enhance our course community building, I am now fortunate to be able to offerings and departmental vision for mathematical say “yes!” to more of these requests, and for that I am data science. The other two positions fill a vacancy left very grateful. With such talented students and faculty by Rachel Levy (who became deputy executive director we have many great ideas and activities to consider, and of the Mathematical Association of America in 2018) and we appreciate your continued interest and support of our a pending vacancy due to Nick Pippenger’s retirement at department. -

Current Newsletter: Summer 2021

1 Volume LII Number 2 The National Association of Mathematicians (NAM) publishes the NAM Newsletter four times per year. Editor always had as its main objectives, the promotion of excel- Dr. Haydee Lindo (Harvey Mudd College) lence in the mathematical sciences and the promotion and [email protected] mathematical development of under-represented minority https://www.linkedin.com/in/haydee-lindo-phd mathematicians and mathematics students. It also aims to address the issue of the serious shortage of minorities in the Editorial Board workforce of mathematical scientists. Dr. Mohammad K. Azarian (University of Evansville) [email protected] NAM’s National Office, subscriptions and mem- http://faculty.evansville.edu/ma3/ bership: National Association of Mathematicians, 2870 Peachtree Rd NW #915-8152, Atlanta, GA 30305; e-mail: Dr. Nadia Monrose Mills (University of the Virgin Islands) [email protected]. [email protected] www.uvi.edu/directory/profiles/faculty/mills-nadia-m.aspx NAM’s Official Webpage: http://www.nam-math.org Dr. Noelle Sawyer (Southwestern University) Newsletter Website: The NAM website has a list [email protected] of employment as well as summer opportunities on the https://noellesawyer.com Advertisements page. It also features past editions of the Newsletter on the Archives page. NAM’s History and Goals: The National Association of Mathematicians, Inc. (known as NAM) was founded Letters to the editor and articles should be addressed in 1969. NAM, a nonprofit professional organization, has to Dr. Omayra Ortega via e-mail to [email protected]. From the Editor Hello friends, ing the larger mathematical community for the bet- As I have been edit- ter.