LD5655.V855 1990.M454.Pdf (4.748Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2010 Newsletter

May 2010 I Salute The Confederate Flag With Affection, Reverence, and Undying Devotion to the Cause for Which It Stands. Commander : David Allen 1st Lieutenant Cdr : From The Adjutant John Harris 2nd Lieutenant Cdr & Gen. RE Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, will meet at 7 PM Thursday Adjutant : night, May 13th, 2010, at the Tuscaloosa Public Library. Frank Delbridge Our speaker for the evening will be the Editor-in-Chief of the magazine "Southern Times Color Sergeant : of Greater Tuscaloosa", Mr. James Crawford II. For 15 years the Southern Times published Clyde Biggs the stories and reminisces of people from all walks of Tuscaloosa's unique Southern lifestyle. Chaplain : Mr. Crawford will tell how the new management team of the publication intends to pub- Dr. Wiley Hales lish it under a bi-monthly schedule. He will speak on the importance of preserving the "truly Newsletter : southern art of storytelling", the basic tenets of passing heritage and family values from one James Simms generation to another and some of the techniques for engaging the younger generation. Let's [email protected] have a good turnout for this event. Website : Brad Smith We had a good turn-out for our Confederate Memorial Day ceremony at Nazareth Primi- [email protected] tive Baptist Church, many of the church members who had Confederate ancestors buried there came to the ceremony and spoke about their ancestors when given the opportunity to do INSIDE THIS so. We need to think about finding another historic church with Confederate soldiers buried in ISSUE its cemetery for a future ceremony. -

Record of the Organizations Engaged in the Campaign, Siege, And

College ILttirarjj FROM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ' THROUGH £> VICKSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK COMMISSION. RECORD OF THE ORGANIZATIONS ENGAGED IN THE CAMPAIGN, SIEGE, AND DEFENSE OF VICKSBURG. COMPILED FROM THE OFFICIAL RECORDS BY jomsr s. KOUNTZ, SECRETARY AND HISTORIAN OF THE COMMISSION. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1901. PREFACE. The Vicksburg campaign opened March 29, 1863, with General Grant's order for the advance of General Osterhaus' division from Millikens Bend, and closed July 4^, 1863, with the surrender of Pem- berton's army and the city of Vicksburg. Its course was determined by General Grant's plan of campaign. This plan contemplated the march of his active army from Millikens Bend, La. , to a point on the river below Vicksburg, the running of the batteries at Vicksburg by a sufficient number of gunboats and transports, and the transfer of his army to the Mississippi side. These points were successfully accomplished and, May 1, the first battle of the campaign was fought near Port Gibson. Up to this time General Grant had contemplated the probability of uniting the army of General Banks with his. He then decided not to await the arrival of Banks, but to make the cam paign with his own army. May 12, at Raymond, Logan's division of Grant's army, with Crocker's division in reserve, was engaged with Gregg's brigade of Pemberton's army. Gregg was largely outnum bered and, after a stout fight, fell back to Jackson. The same day the left of Grant's army, under McClernand, skirmished at Fourteen- mile Creek with the cavalry and mounted infantry of Pemberton's army, supported by Bowen's division and two brigades of Loring's division. -

Congressional Record-House. 3835

1886. CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE. 3835 died and where there are the best facilities for handling it cheaper than may not within 10 miles of the city of New York charge the same rate it can be done at a place where there is very little business done and or double the rate that it charges all the way from Chicago to New no facilities for handling it. Now, I will hear the Senator from Ten York. nessee. Mr. WILSON, of Iowa. That is a difficulty which has occurred to Mr. HARRIS. Under the provisions of the bill as it stands, taking my mind. Undoubtedly if the language of the bill is left as it now the illustration from Chicago to New York, every shipment made from stands the implication iB unavoidable that a common carrier within the Chicago, whether to New York or any intermediate point on the line of terms of the bill may charge a rate as great for 500 miles as for a thou· road, is subject to this provision, and the shorter haul can not be forced sand miles. to pay more than the aggregate amount paid on the longer; but if you Mr. HARRIS. Yes; or for 11 miles. take up a shipment midway between Chicago and New York, at a way Mr. WILSON, of Iowa. ·That would be the legitim~tte and necessa.ry station, of one or fifty car-loads of freight, that shipment is not in any implication arising upon the language of the bill. Therefore I desite wise subject to the provisions of the bill. -

May 2011 Newsletter

May 2011 I Salute The Confederate Flag With Affection, Reverence, and Undying Devotion to the Cause for Which It Stands. From The Adjutant Commander : David Allen 1st Lieutenant Cdr : Gen. RE Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, will meet Thursday night, John Harris May 12, 2011, at 7 PM in the Tuscaloosa Public Library. 2nd Lieutenant Cdr & Adjutant : Members who have not yet paid their dues are reminded that re-instatement fees of Frank Delbridge $7.50 are added , and their total dues are now $67.50. Color Sergeant : Clyde Biggs Chaplain : Dr. Wiley Hales Newsletter : James Simms [email protected] Website : Brad Smith [email protected] INSIDE THIS ISSUE 2 General Rodes 5 Local Reenactment Dates 6 Historical Marker 6 Website Report 7 Confederate Gen'ls Birthdays 8 AL Civil War Units Upcoming Events 10 CWT News 13 Homesick For Eden 15 Robert E. Lee 16 North Celebrations 12 May - Camp Meeting 18 BattleFlag 18 Confederate Veterans 9 June - Camp Meeting 14 July - Camp Meeting August - Summer Bivouac / Stand Down 8 September - Camp Meeting 13 October - Camp Meeting 23 October - Thisldu - TBD 2 The Robert E. Rodes Camp #262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, wish to express sincere condolences and sorrow to the people of Tuscaloosa who have lost loved ones or property in their recent tragedy. 3 The Rodes Brigade Report is a monthly publication by the Robert E. Rodes SCV Camp #262 to preserve the history and legacy of the citizen-soldiers who, in fighting for the Confederacy, personified the best qualities of America. The preservation of liberty and freedom was the motivating factor in the South's decision to fight the Second American Revolution. -

The Family Bible Preservation Project Has Compiled a List of Family Bible Records Associated with Persons by the Following Surname

The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry THE FAMILY BIBLE PRESERVATION PROJECT HAS COMPILED A LIST OF FAMILY BIBLE RECORDS ASSOCIATED WITH PERSONS BY THE FOLLOWING SURNAME: BAKER Scroll Forward, page by page, to review each bible below. Also be sure and see the very last page to see other possible sources. For more information about the Project contact: EMAIL: [email protected] Or please visit the following web site: LINK: THE FAMILY BIBLE INDEX Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: BAKER UNDER THIS SURNAME - A FAMILY BIBLE RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: FAMILY OF: BAKER, A SPOUSE: EAS OEHLER MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS BIBLE - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: E. C. SLAYOR FAMILY BIBLE TRANSCRIPTION COLLECTION PAGE: FILE/RECD: RECORD OF: BAKER, A THE FOLLOWING INTERNET HYPERLINKS CAN BE HELPFUL IN FINDING MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THIS FAMILY BIBLE: LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK LINK: CLICK HERE TO ACCESS LINK GROUP CODE: 31 Copyright - The Family Bible Preservation Project The Family Bible Preservation Project's - Family Bible Surname Index - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Page Forward to see each Bible entry SURNAME: BAKER UNDER THIS SURNAME - A FAMILY BIBLE RECORD EXISTS ASSOCIATED WITH THE FOLLOWING FAMILY/PERSON: FAMILY OF: BAKER, AARON (1810-1897) SPOUSE: MARY HEARTLEY MORE INFORMATION CAN BE FOUND IN RELATION TO THIS BIBLE - AT THE FOLLOWING SOURCE: SOURCE: ONLINE INDEX: D.A.R. -

Conflict and Controversy in the Confederate High Command: Johnston, Davis, Hood, and the Atlanta Campaign of 1864

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-1-2013 Conflict and Controversy in the Confederate High Command: Johnston, Davis, Hood, and the Atlanta Campaign of 1864 Dennis Blair Conklin II University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Conklin, Dennis Blair II, "Conflict and Controversy in the Confederate High Command: Johnston, Davis, Hood, and the Atlanta Campaign of 1864" (2013). Dissertations. 574. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/574 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi CONFLICT AND CONTROVERSY IN THE CONFEDERATE HIGH COMMAND: JOHNSTON, DAVIS, HOOD, AND THE ATLANTA CAMPAIGN OF 1864 by Dennis Blair Conklin II Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ABSTRACT CONFLICT AND CONTROVERSY IN THE CONFEDERATE HIGH COMMAND: JOHNSTON, DAVIS, HOOD, AND THE ATLANTA CAMPAIGN OF 1864 by Dennis Blair Conklin II May 2013 The Union capture of Atlanta on September 2, 1864 all but assured Abraham Lincoln's reelection in November and the ultimate collapse of the Confederacy. This dissertation argues that Jefferson Davis's failure as commander-in-chief played the principal role in Confederate defeat in the war's most pivotal campaign. Davis had not learned three important lessons prior to the campaign season in 1864. -

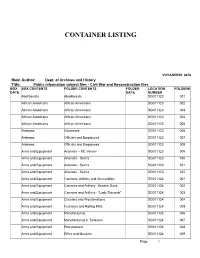

Container Listing

CONTAINER LISTING VOYAGERID: 6478 Main Author: Dept. of Archives and History Title: Public information subject files - Civil War and Reconstruction files BOX BOX CONTENTS FOLDER CONTENTS FOLDER LOCATION FOLDER# DATE DATE NUMBER Abolitionists Abolitionists SG011123 001 African Americans African Americans SG011123 002 African Americans African Americans SG011123 003 African Americans African Americans SG011123 004 African Americans African Americans SG011123 005 Alabama Governors SG011123 006 Alabama Officials and Employees SG011123 007 Alabama Officials and Employees SG011123 008 Arms and Equipment Arsenals -- Mt. Vernon SG011123 009 Arms and Equipment Arsenals - Selma SG011123 010 Arms and Equipment Arsenals - Selma SG011123 011 Arms and Equipment Arsenals - Selma SG011123 012 Arms and Equipment Cannons. Artillery and Ammunition SG011124 001 Arms and Equipment Cannons and Artillery - Brooke Guns SG011124 002 Arms and Equipment Cannons and Artillery - "Lady Slocomb" SG011124 003 Arms and Equipment Circulars and Proclamations SG011124 004 Arms and Equipment Furnaces and Rolling Mills SG011124 005 Arms and Equipment Manufacturing SG011124 006 Arms and Equipment Manufacturing in Tallassee SG011124 007 Arms and Equipment Procurement SG011124 008 Arms and Equipment Rifles and Muskets SG011124 009 Page: 1 Arms and Equipment Small Arms (inc. Pistols, Sabers and SG011124 010 Pikes) Army (General information) SG011124 011 Army (General information) SG011124 012 Army Alabama Generals and Aide-de-Camps SG011124 013 Army Alabama Troops - Local Designations SG011125 001 Army Appointments by Gov. Moore - 1861 SG011125 002 Army Balloon Service SG011125 003 Army Provost Marshalls SG011125 004 Army Recruitment SG011125 005 Army Secret Service SG011125 006 Bibliography Alabama in the War SG011125 007 Biography ADAH Correspondence SG011125 008 Biography Adams - Bunting SG011125 009 Biography Cleburne - Griffen SG011125 010 Biography Hannon - Kelly SG011125 011 Biography Law - Nott SG011125 012 Biography O'Neal - Tracy SG011125 013 Biography Webb - Wood SG011125 014 Biography Allen. -

This Page Intentionally Left Blank. History of the 3D, 7Th, 8Th and 12Th Kentucky

This page intentionally left blank. History of the 3d, 7th, 8th and 12th Kentucky BY • HENRY GEORGE May, 1911 p. T. DlEARIN G PRINTI I4G CO. IHCORPORATCD LO UISVILLE, K Y. III:M."I i.i.i ii:i.i CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE Constitutional Rights to Secede, incjucling the Origin of the Negro Traffic ...'................: n CHAPTER n. Organization of the Third and Eighth Kentnckv; Their Move ment up to and IncUiding the Battle of Fort Donalson and Shiloh 19 CHAPTER HI. Organization of the Seventh Kentucky; Their Movement up to and' Including the Battle of Shiloh 2^ CHAPTER IV. Operations About Corinth; Movement Back' to Tupelo and on to Vicksburg 33 CHAPTER V. Movement South Under John C. Breckinridge; Battle of Baton Rouge, and Occupancy of Port Hudson 36 CHAPTER VI. Movement in the North Mississippi under Van Dorn. Price and Van Dorn Unite Their Commands and Make an l^nsuccessful Attack on the Federals under Rosecrans at Corinth 47 CHAPTER VII. Movement in Front of Grant; Holly Springs, Grenada and Talla hatchie, Back to Vicksburg; Big Black and to the Battle of Baker's Creek 54 CHAPTER VIII. Mistakes of Pemberton. General Joseph E. Johnston, at Jackson, Movfid to Big Black in Rear of Grant; Fell Back to Jackson, Where There Was Some Fighting; Moved Back to Meridian; Moved to Canton, Where They Remained During the Winter. Organization of the Twelfth Kentucky, and the Battle of Okolona 64 CHAPTER IX, Kentuckians Mounted and Put Under Forrest; Moved North Through Tennessee; Captured Union City and Attacked Pa- ducah. Command Visited Their.Homes First Time in Three Years or Since the War Commenced 74 CHAPTER X. -

The Confederate Defense of Mobile, 1861-1865. (Volume I and Volume Ii)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 The onfedeC rate Defense of Mobile, 1861-1865. (Volumes I-Ii). Arthur William Bergeron Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Bergeron, Arthur William Jr, "The onfeC derate Defense of Mobile, 1861-1865. (Volumes I-Ii)." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3511. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3511 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. -

“Between Two Fires”: War and Reunion in Middle America, 1860-1899

“Between Two Fires”: War and Reunion in Middle America, 1860-1899 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2013 By Matthew E. Stanley M.A., University of Louisville, 2007 B.A., University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 2005 Committee Chair: Professor Christopher Phillips Abstract From its post-Revolutionary position as the First West to its current status as a political bellwether, the Ohio Valley has always been a liminal space in American history. This dissertation centers on the Civil War, Reconstruction, and sectional reconciliation in the Lower Middle West, with particular emphases on identity, memory, and race. Indeed, if the antebellum West acted as balance between North and South, then the Lower Middle West, a nominally free region dominated by conservative upland Southern political culture, represented a median with the median. The Lower Middle West—part of a vast border area stretching from southern Pennsylvania and northern Virginia along the Ohio River Valley and into Missouri and Kansas that I term ‘Middle America’—was a political and cultural middle space typified by white conservative Unionism. Wartime conservative Unionists—those whites who supported compromise measures, desired only the political restoration of the Union, and who persisted rather than embraced emancipation—are central to understanding the dissent (Copperhead) movement, the Northern white backlash against liberalizing war measures, the Northern rejection of Congressional Reconstruction, the national movement toward sectional reconciliation among whites, and the legacies of white supremacy in the Middle West (labor violence, exclusion laws, sundown towns, lynching, the second incarnation of the KKK). -

The Buford Expedition to Kansas

THE BUFORD EXPEDITION TO KANSAS BY the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed by Congress in I854, the Territories of Kansas and Nebraska were organized and thrown open to settlement with the proviso that all questions relating to slavery were to be decided by the people of each territory when it should be ready for admission into the Union as a state. The South conceded and the North was sure of the admission of Ne- braska as a free state. In the case of Kansas it was doubtful if the anti-slavery party would ever be strong enough to control the elec- tions, but the leaders at the North intended to make a fight to secure Kansas. Consequently there was great excitement in differ- ent sections of the country, especially at the North, where, almost before the bill became a law, Emigrant Aid Societies were formed whose object was to assist emigrants opposed to the institution of slavery to go to the territory and settle in order to be ready to vote at the proper time. In this movement of importing men the North had nearly two years the start, the South being confident that no exertion would be necessary in order to secure Kansas as a slave state. So there was very little pro-slavery emigration into this " debatable land " before late in I855 except from the neighboring state of Missouri. The first territorial elections were in favor of the Southern party, but the Emigrant Aid Societies in the Northern states kept pouring men and arms into the territory until late in I855 the outlook was gloomy for the pro-slavery cause. -

The Confederate Surrender at Tiptonville and the Conclusion of the Island No. 10 Campaign

The Confederate Surrender at Tiptonville and the Conclusion of the Island No. 10 Campaign Dieter C. Ullrich In the early morning hours of April 7, 1862, the skies above the headquarters of Brigadier General John Pope near New Madrid, Missouri flashed with lightning, rumbled with thunder, and rain poured down in sheers. Pope, unable to sleep, paced anxio usly inside a modest single-story clap board ho use thar served as the command center for the recently created Army of the Mississippi. Though the severity of the weather concerned him, he could wa it no lo nger and gave the final order to proceeJ at daylight with the bombardment of the Confederate batteries o n the Kentucky shore. Afte r the long-range artillery softened the rebel defenses, two ironclad gunboats would steam down river and shell what remained of the enemy batteries at close range. When the batteries were silenced four tran sports loaded with a division of infantry, a w mpany of sharpshooters, two companies of cavalry and a battery of light artillery wo uld cross the river, form a perimeter and dig in. Wirh a foothold o n Kentucky soil, Pope could land bis entire force and dislodge the enemy from Madrid Bend and Island No. 10. At least that was the plan, but no Army had ever attempted to traverse a rapid and high rising river over a mile wide, under enemy fire, and dislodge an entTenchcd foe of over an estimated 7,500 men. Pope, no netheless, was confident of success. 1 Pope later in the w;1r became a contentious figu re, but at that moment he was a rising star in the Union Army out to make his mark.