Jonathan Littell's the Kindly Ones (2010) and Martin Amis' the Zone of Interest (2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bennett V. Spear and the Past and Future of Standing in Environmental Cases

STANDING ON ITS LAST LEGS: BENNETT V. SPEAR AND THE PAST AND FUTURE OF STANDING IN ENVIRONMENTAL CASES STANDING ON ITS LAST LEGS: BENNETT V. SPEAR AND THE PAST AND FUTURE OF STANDING IN ENVIRONMENTAL CASES SAM KALEN[*] Copyright © 1997 Florida State University Journal of Land Use & Environmental Law No man is an IIand, intire of itselfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a Clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.[1] BLOCKQUOTE> I. INTRODUCTION The law of "standing" in environmental disputes appears to be resting on its last legs, and well it should be. Arguably, standing's fate has been sealed since its conception in the 1970s.[2] Now, approximately a quarter of a century later, standing is on the verge of collapsing onto its weak intellectual foundation. The standing doctrine is that part of the "law of judicial jurisdiction" that "determines whom a court may hear make arguments about the legality of an official decision."[3] Almost twenty years ago, Joseph Vining viewed standing with "a sense of intellectual crisis."[4] In the years since, that intellectual crisis has grown. The Supreme Court's recent decision in Bennett v. Spear[5] reflects one aspect of how this crisis has become too unwieldy. -

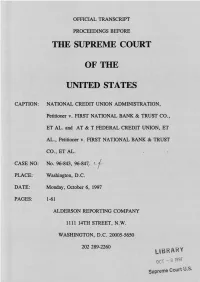

96-843

OFFICIAL TRANSCRIPT PROCEEDINGS BEFORE THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES CAPTION: NATIONAL CREDIT UNION ADMINISTRATION, Petitioner v. FIRST NATIONAL BANK & TRUST CO., ET AL. and AT & T FEDERAL CREDIT UNION, ET AL., Petitioner v. FIRST NATIONAL BANK & TRUST CO., ET AL. CASE NO: No. 96-843, 96-847, l <L PLACE: Washington, D.C. DATE: Monday, October 6, 1997 PAGES: 1-61 ALDERSON REPORTING COMPANY 1111 14TH STREET, N.W. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-5650 202 289-2260 , v LIBRARY OCT ~ 8 1997 Supreme Court U. RECEIVED SUPREME COURT. U.S MARSHAL'S Of F ICE *97 OCT -7 All 22 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 2 X 3 NATIONAL CREDIT UNION : 4 ADMINISTRATION, : 5 Petitioner : 6 v. : No. 96-843 7 FIRST NATIONAL BANK & TRUST CO., : 8 ET AL.; : 9 and : CONSOLIDATED 10 AT&T FEDERAL CREDIT UNION, ET AL., : 11 Petitioner : 12 v. : No. 96-847 13 FIRST NATIONAL BANK & TRUST CO., : 14 ET AL. : 15 ----------------- -X 16 Washington, D.C. 17 Monday, October 6, 1997 18 The above-entitled matter came on for oral 19 argument before the Supreme Court of the United States at 20 10:05 a.m. 21 APPEARANCES: 22 SETH P. WAXMAN, ESQ., Acting Solicitor General, Department 23 of Justice, Washington, D.C.; on behalf of the Federal 24 Petitioner. 25 JOHN G. ROBERTS, JR., ESQ., Washington, D.C.; on behalf of 1 ALDERSON REPORTING COMPANY, INC. 1111 FOURTEENTH STREET, N.W. SUITE 400 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 (202)289-2260 (800) FOR DEPO 1 the Private Petitioners. -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS New (4) Copia

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS KEYNOTE LECTURES • CHEYETTE, BRYAN [email protected] University of Reading (UK) “The Contemporary Novel, Reality Hunger and the Memory Boom” This lecture will explore the tensions between historical understanding and memory studies with particular reference to the Holocaust and decolonization (under the sign of the post- 1990s “memory boom”). After the exhaustion of “postmodernism” and “postcolonialism” as master signifiers of the contemporary, recent influential narratives —such as David Shields’ “reality hunger” or Michael Rothberg’s “multidirectional memory”— may, I will argue, unwittingly reinforce long-standing binaries between memory and history, fluidity and rigidity, subjectivity and objectivity, the real and the imagined. The lecture will be illustrated from the fiction, memoirs and histories of a wide range of imaginative writers, memoirists, and intellectuals in a bid to both bring together new comparative histories and show how the “memory boom” has made such comparative work particularly challenging. • EAGLESTONE, ROBERT [email protected] Royal Holloway, University of London (UK) “Telos and Trauma” The cluster of ideas around trauma, violence and testimony mark one connection between literature, the past and ethics. Recent research in the field has explored both the frequent elision of the world outside Europe in these debates and the ways in which “memories are mobile … [and] histories are implicated in each other” (Rothberg). The aim of this, in turn, has been the hope that these aspects -

The Zone of Interest Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE ZONE OF INTEREST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Amis | 320 pages | 21 Aug 2014 | Vintage Publishing | 9780224099745 | English | London, United Kingdom The Zone of Interest PDF Book There are many reasons to avoid this book. How are others finding it?. Play the game. The identical fear has brought many survivors to choose silence, and in silence they still live today. Thomsen becomes enamored with Doll's wife Hannah. About this book. This mirror didn't show you your reflection. I wonder if this isn't really a novel for future generations, which might perhaps join Tadeusz Borowski's This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen and a few other books as a concise introductory to the era's horrors. Instead, what is truly exceptional about this book is what it says about men and masculinity within those notions. Szmul though and the ethical and physical horror he undergoes every day, not surprisingly, eludes Amis. Caught doing something plainly disgusting. In some ways, I respect this approach. I will say that it was an interesting read as apart from The Reader i haven't read 'the other side of the story', but it's not for the faint hearted. Lastly, there is Szmul, a Jewish prisoner, who works at the ramp where the prisoners arrive on the trains and who is a witness to all the atrocities that happen around him. Granted, it would be very difficult for any writer, no matter how talented, to pull off a combination love story and office comedy set within the higher bureaucracy of a concentration camp. -

SVWC 2019 Reading List for Website

2019 Reading List Martin Amis The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump: Essays and Reportage, 1994-2017 (2018) The Zone of Interest (Vintage International) (2015)reprint Experience:A Memoir (2014) Kobe the Dread (2014) Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012) The Pregnant Widow (2011) Heavy Water and Other Stories (2011) Other People (2010) The Second Plane (2009) House of Meeting (2007) Vintage Amis (2007) Yellow Dog (2005) The War Against Cliche (2002) Experience (2000) Night Train (1999) The Information (1996) Visiting Mrs. Nabokov (1995) Times Arrow (1992) Dead Babies (1991) Success (1991) The Moronic Inferno (1991) Einstein’s Monsters (1990) London Fields (1989) Money:A Suicide Note (1984) Invasion of the Space Invaders (1992) The Rachel Papers (1973) Kwame Anthony Appiah The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity (2018) As If: Idealization and Ideals (2017) Lines of Descent (2014) The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen (2011) Cosmopolitanism:Ethics in a World of Strangers (2010) Encyclopedia of Africa (2010) Experiments in Ethics (2008) The Ethics of Identity (2005) Thinking It Through (2003) Color Conscious (1998) Nobody Likes Letina (1994) In My Father’s House (1993) Avenging Angel (1991) Necessary Questions(1989) Rick Atkinson The British Are Coming:The War for America, Lexington to Princeton (2019) The Guns at Last Night:The War in Western Europe 1944-1945 (2014) D-Day:The Invasion of Normandy 1944 (2014) The Long Gray Line:The American Journey of West Point’s Class of 1966 (2009) In the Company of Soldiers:A -

More Than Words Reflections on the Zone of Interest, the Sonderkommando, Testimony, and Liminality

More than Words Reflections on The Zone of Interest, the Sonderkommando, Testimony, and Liminality Juliette van Kesteren 4218078 Supervised by: Dr. L. Munteán, Radboud University Nijmegen Dr. J.A. Jordan, University of Southampton Radboud University Nijmegen A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree Master of Arts in English Literary Studies 8 November 2016 Abstract This MA thesis discusses Martin Amis’ 2014 novel The Zone of Interest and the way it portrays and represents the Sonderkommando through intertextual and historical references, the characterisation the main characters and the use of testimony. The zone of interest (German: Interessengebiet) was the area surrounding a concentration camp which was cleared of its native population and original structures. The novel was named after this area and tells the story of a concentration camp through four different characters: camp commandant Paul Doll and his wife Hannah, government liaison Angelus Thomsen and Sonderkommandoführer Szmul. The research question was: How is the Sonderkommando represented in The Zone of Interest and how does Martin Amis deal with this through intertextual and historical references, notions of liminality, and testimony? First, the novel and the Sonderkommando are introduced and the thesis is outlined in the introduction, and then three chapters discuss the novel and the Sonderkommando from various viewpoints. The conclusion was that the book paints an image of the Sonderkommando as moral, pained, thoughtful people, through Szmul’s narrative. This is in contrast with many views, including that of Primo Levi, whose work inspired Amis in writing this book. Through intertextual references, Amis engages in a critical conversation with Levi, Arendt and Bauman on various topics. -

SVWC 2019 Reading List Full.Xlsx

SVWC 2019 Master Reading List Martin Amis The Rub of Time: Bellow, Nabokov, Hitchens, Travolta, Trump: Essays and Reportage, 1994-2017 (2018) The Zone of Interest (2015) Experience: A Memoir (2014) Kobe the Dread (2014) Lionel Asbo: State of England (2012) The Pregnant Widow (2011) Heavy Water and Other Stories (2011) Other People (2010) The Second Plane (2009) House of Meeting (2007) Vintage Amis (2007) Yellow Dog (2005) The War Against Cliche (2002) Experience (2000) Night Train (1999) The Information (1996) Visiting Mrs. Nabokov (1995) Times Arrow (1992) Dead Babies (1991) Success (1991) The Moronic Inferno (1991) Einstein’s Monsters (1990) London Fields (1989) Money: A Suicide Note (1984) Invasion of the Space Invaders (1992) The Rachel Papers (1973) Kwame Anthony Appiah The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity (2018) As If: Idealization and Ideals (2017) Lines of Descent (2014) The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen (2011) Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers (2010) Encyclopedia of Africa (2010) Experiments in Ethics (2008) The Ethics of Identity (2005) Thinking It Through (2003) Color Conscious (1998) Nobody Likes Letina (1994) 1 In My Father’s House (1993) Avenging Angel (1991) Necessary Questions(1989) Rick Atkinson The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton (2019) The Guns at Last Night: The War in Western Europe 1944-1945 (2014) D-Day: The Invasion of Normandy 1944 (2014) The Long Gray Line: The American Journey of West Point’s Class of 1966 (2009) In the Company of Soldiers: A Chronicle -

Summer Reading List

Summer Reading List AP Literature 2015-2016 Contact information: All assignments and information are posted electronically on the blog: http://mrgiorgi.blogspot.com and the teacher site (https://sites.google.com/a/nhsd.org/nhsgiorgi/). I can also be reached by email: [email protected], [email protected] (in case there is problem with school email) Required Books—your responsibility You should read each of the following five (5) books during summer break. You should take notes on each in a journal, on note cards, or in a computer file you can easily reference when you return to school. Read the Thomas Foster book first For this book make notes on each chapter as he always gives you something to look for. Read the novels in any order you like For each of the five novels, it is suggested that you keep a record of the following using the attached Sample Reading Summer Sheet: Basic plot points Main characters and brief description of each Important symbols and explanations At least two important themes from each book with appropriate commentary on each Any additional information that will help you in class. Required Writing—your responsibility Write your College Essay (50 points) From the Common App: “Please write an essay (250 words minimum) on a topic of your choice or on one of the options listed below, and attach it to your application before submission. Please indicate your topic by checking the appropriate box. This personal essay helps us become acquainted with you as a person and student, apart from courses, grades, test scores, and other objective data. -

Jonathan Littell's the Kindly Ones (2010) and Martin Amis' the Zone of Interest (2014)

Lola Serraf Master of Arts in Advanced English Studies: Literature Narrative perspective in two contemporary perpetrator novels: Jonathan Littell's The Kindly Ones (2010) and Martin Amis' The Zone of Interest (2014) Supervised by Professor Andrew Monnickendam July 2015 Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Germanistica Lola Serraf Driven by thirst, I eyed a fine icicle outside the window, within hands reach. I opened the window and broke off the icicle but at once a large, heavy guard prowling outside brutally snatched it away from me. “Warum?” I asked him in my poor German. “Hier ist kein warum” (there is no why here), he replied, pushing me inside with a shove. (Levi 1996: 29) 1 Lola Serraf Acknowledgments This dissertation would not have been possible without the help of many people. I wish to thank in particular Professor Andrew Monnickendam, who is both an excellent teacher and an outstanding supervisor, for taking the time to read my countless drafts and always giving me invaluable advice and guidance. I also wish to thank Dr. Jordi Coral, whose classes on the MA course were I believe not only interesting but also extremely useful in terms of academic writing skills. Moreover, many thanks to Professor Aránzazu Usandizaga, Dr. Sara Martín, Dr. Cristina Pividori and Dr. David Owen, for reading my work and giving me constructive and useful feedback. I also want to express my deepest gratitude to my parents, Hugues Serraf and Caroline Lopez, who have encouraged and supported me throughout my research. 2 Lola Serraf Formatting This dissertation has been written in general agreement with the guidelines established by the 2009 MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (seventh edition) 3 Lola Serraf Contents Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. -

The Reception of the Zone of Interest by Martin Amis in the English, American, German and Polish Literary and Critical Circulation

Uniwersytet Humanistyczno - Przyrodniczy im. Jana Długosza w Częstoc h o w i e TRANSFER 2018, t. III, s. 183–199 Reception Studies http://dx.doi.org/10.16926/trs.2018.03.07 Paulina KASIŃSKA https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2393-5090 Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa (Częstochowa) The reception of The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis in the English, American, German and Polish literary and critical circulation Summary: The author, analysing the critical-literary discussions in online daily press, shows that Martin Amis’s The Zone of Interest received extremely mixed reviews. The novel was well received by English and American critics, but the reviews in Germany were rather negative. In Poland, The Zone of Interest received mixed reviews and the novel was hardly noticeable in the reading reception. According to the author, the reason for the polarized opinions of critics is the increased sensitivity of nations directly affected by the policy of the Third Reich to an unconventional approach to Holocaust literature, which aims to rework the trauma through breaking the Holocaust taboo. Keywords: Martin Amis, The Zone of Interest, literary criticism, Holocaust, novel, trauma. Although 72 years have passed since the end of the Second World War, Holocaust representation is still a matter of heated dispute. The events which took place between 1939 and 1945 were disastrous for humankind in so many respects that the question whether they should be represented in literature resurfaces continually. Thane Rosenbaum, an American writer whose both parents were prisoners of Nazi concentration camps, argues that only Holocaust survivors have the right to speak about those events as they experienced the war atrocities firsthand – their memories may be turned into testimonies or accurate literary representations. -

A Proletarian Comedy of Menace: Martin Amis's Lionel Asbo

85 SUSANNE PETERS A Proletarian Comedy of Menace: Martin Amis's Lionel Asbo 1. The Principle of Terrestrial Mediocrity One of the familiar and often controversially discussed topics of Amis criticism is to point out how, in his novels, everything is going to the dogs.1 Lionel Asbo: State of England,2 published shortly before Amis's relocation to New York in 2012, takes this bone of contention to new heights in both a literal and a metaphorical sense: dogs play a major role in the novel's configurations of anxiety, but our metaphor of course, and more importantly, also reflects Amis's idiosyncratic diagnosis of a decrepit, violently ignorant English society, as his novel's subtitle aptly flags out: Its eponymous protag- onist, a violent and ignorant criminal, assisted by his pair of pitbulls fed on Tabasco sauce and Cobra beer, is an allegory of the state of England. In this essay, I shall dis- cuss whether it is a humorous one. Martin Amis has found an intriguing phrase for what he thinks is happening in our Western societies today. It is "the principle of terrestrial mediocrity," (129) as the protagonist and writer Richard Tull (whom we can take as the ventriloquist Amis's dummy) assumes in Amis's 1995 novel The Information and it is further elaborated as guiding the development of human communities and the history of all art, especially literature: It inevitably leads to moral decay, and finds 20th-century culture in a state of exhaustion. Such downward spiralling history of humankind is aligned with the history of astronomical discoveries, in which man likewise seems to dwindle into insignificance – both processes of persistent humiliation.3 Perhaps the most character- istic (and often quoted) passage yet in this context can indeed be found in The Infor- mation, where Richard Tull is questioned by his editor about a new book project: 'What's this? The History of Increasing Humiliation. -

Legal Updates 2018

Legal Updates 2018 Program Moderator: Day One: Susan Damron, Director of Educational Programs (OKC), Susan Carey (Tulsa) and Day Two: Jim Calloway, Director, Management Assistance Programs OBA/CLE DEPARTMENT Susan Damron, Esq., Director of Educational Programs Jennifer Wynne, Program Manager Mark Schneidewent, Online Manager Renee Montgomery, Registrar Gary Berger, Production Specialist Table of Contents Legal Updates 2018 Day 1 A. Bar Ad B. General Seminar Information C. Biographies D. Bankruptcy Law Update Sam G. Bratton, II, Doerner Saunders Daniel & Anderson, Tulsa E. Labor and Employment Law Update Tulsa Program: Courtney Bru, McAfee & Taft, Tulsa Oklahoma City Program: Josh Solberg, McAfee & Taft, Oklahoma City F. Health Law Update Tulsa Program: David Hyman, Tulsa Oklahoma City Program: Karen S. Rieger, Crowe & Dunlevy, Oklahoma City G. Criminal Law Update Barry L. Derryberry, Assistant Federal Public Defender, Tulsa H. Oklahoma Tax Law Update Tulsa Program: Sheppard Miers, Gable Gotwals, Tulsa Oklahoma City Program: Kevin Ratliff, Ratliff Law Firm, Oklahoma City I. Insurance Law Update Rex Travis, Travis Law Office, Oklahoma City Legal Updates 2018 Tulsa Oklahoma City DATES & Thurs., Nov. 29 & Fri., Nov. 30, 2018 Thurs., Dec. 13 & Fri., Dec. 14, 2018 LOCATIONS: DoubleTree by Hilton Tulsa Warren Place Oklahoma Bar Center 6110 S Yale Ave, Tulsa, OK 74136 1901 N. Lincoln Blvd., OKC, OK 73105 CLE CREDIT: 12/1 Both Days: 6/0 Day One: 6/1 Day Two 5/0 Texas MCLE Day One: 5/.75 Texas MCLE Day Two DAY ONE Program Moderator Susan Carey, Tulsa Susan Damron, Director of Educational Programs, Oklahoma Bar Association (OKC) 8:30 a.m. Registration and Continental Breakfast 9:00 Bankruptcy Law Update Sam G.