Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

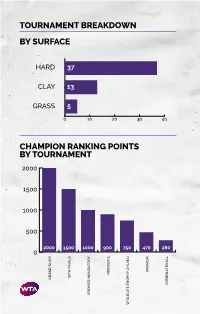

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

WTT . . . at a Glance

WTT . At a glance World TeamTennis Pro League presented by Advanta Dates: July 5-25, 2007 (regular season) Finals: July 27-29, 2007 – WTT Championship Weekend in Roseville, Calif. July 27 & 28 – Conference Championship matches July 29 – WTT Finals What: 11 co-ed teams comprised of professional tennis players and a coach. Where: Boston Lobsters................ Boston, Mass. Delaware Smash.............. Wilmington, Del. Houston Wranglers ........... Houston, Texas Kansas City Explorers....... Kansas City, Mo. Newport Beach Breakers.. Newport Beach, Calif. New York Buzz ................. Schenectady, N.Y. New York Sportimes ......... Mamaroneck, N.Y. Philadelphia Freedoms ..... Radnor, Pa. Sacramento Capitals.........Roseville, Calif. St. Louis Aces................... St. Louis, Mo. Springfield Lasers............. Springfield, Mo. Defending Champions: The Philadelphia Freedoms outlasted the Newport Beach Breakers 21-14 to win the King Trophy at the 2006 WTT Finals in Newport Beach, Calif. Format: Each team is comprised of two men, two women and a coach. Team matches consist of five events, with one set each of men's singles, women's singles, men's doubles, women's doubles and mixed doubles. The first team to reach five games wins each set. A nine-point tiebreaker is played if a set reaches four all. One point is awarded for each game won. If necessary, Overtime and a Supertiebreaker are played to determine the outright winner of the match. Live scoring: Live scoring from all WTT matches featured on WTT.com. Sponsors: Advanta is the presenting sponsor of the WTT Pro League and the official business credit card of WTT. Official sponsors of the WTT Pro League also include Bälle de Mätch, FirmGreen, Gatorade, Geico and Wilson Racquet Sports. -

Henri Leconte En Plein Doute

LES DÉBUTS DU STADE ROLAND-GARROS . En mai 1928, après cinq mois de travaux, le stade COUPE DAVIS Roland-Garros et son complexe sportif de quatre terrains de tennis sont terminés ! Cette coupe a été créée en 1900 par un jeune étudiant américain Dwight Filley Davis. La Coupe (un bol à es exploits des d’être à la hauteur de cette victoire et punch de 6,750 kg d’argent), à jamais Mousquetaires, Cochet, la faire fructifier. Comme le veut le surnommée « le saladier d’argent », Borotra, Brugnon et principe du Challenge Round, le vain- est donc à l’origine de la création du Lacoste, résonnent aux queur est qualifié directement pour la stade de tennis de la porte d’Auteuil. quatre coins du globe finale. La France doit donc organiser La radio, qui n’a que deux ans d’exis- cet événement et pour cela, elle doit Mais comment faire pour créer ce tence, relaie leurs performances. Au construire un stade à la hauteur de cet stade et trouver son financement : c’est point que tous les regards sont portés exploit pour accueillir la Coupe Davis la grande question ! Un véritable défi surL Paris pour savoir comment va 1928. Neuf mois, c’est le temps pour pour les organisateurs. Aucun club ne se dérouler la prochaine finale de la construire ce stade. La France du ten- peut recevoir cette finale, la plupart Coupe Davis. Ayant remporté l’édition nis a une mission difficile. Mais sont trop petits, leurs infrastructures précédente de 1927, la France se doit « Impossible n’est pas Français » ! existantes sont insuffisantes, même ème celles des prestigieux Racing Club de trouvaille anglaise. -

Tennis-NZ-Roll-Of-Honour V3.Pdf

Tennis New Zealand 2012 HonourRoll of Contents New Zealand Tennis Representatives at the Olympic Games 2 ROLL OF HONOUR New Zealand Players in the final 8 at Grand Slams 2 New Zealand Players in finals at Junior Grand Slams 3 New Zealand in Davis Cup 4 Tennis New Zealand New Zealand Davis Cup Statistics 8 honours the achievements of all New Zealand in Fed Cup 10 the players and administrators National Championships 13 listed here... New Zealand Indoor Championships 16 New Zealand Residential Championships 16 BP National Championships 17 Fernleaf Butter Classic 17 Heineken Open 17 ASB Classic 18 National Teams Event for the Wilding Shield and Nunneley Casket 19 New Zealand Junior Championships 18u 20 National Junior Championships 16u 23 National Junior Championships 14u 24 National Junior Championships 12u 26 National Junior Championships 15u 27 National Junior Championships 13u 27 New Zealand Masters Championships 27 National Senior Championships 28 National Primary/Intermediate Schools Championships 38 Secondary Schools Tennis Championships 39 National Teams Event 16u 40 National Teams Event 14u 40 National Teams Event 12u 41 National teams Event 18u 41 Past Presidents and Board Chairs 42 Life Members 42 Roll of Honour 1 New Zealand Tennis Representatives at the Olympic Games YEAR GAMES NAME EVENT MEDAL 1912 Games of the V A F Wilding Men’s Singles Bronze Olympiad, Stockholm (Australasian Team) (Covered Courts) 1988 Games of the XXIV B J Cordwell Women’s Singles Olympiad, Seoul B P Derlin Men’s Doubles (K Evernden & B Derlin) K G Evernden -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Dissertation As a Partial

Distribution Agreement In presenting this dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non- exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this dissertation. Signature: ____________________________ ______________ Michelle S. Hite Date Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. Hite Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts ___________________________________________________________ Rudolph P. Byrd, Ph.D. Advisor ___________________________________________________________ Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Ph.D. Committee Member ___________________________________________________________ Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Ph.D. Committee Member Accepted: ___________________________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School ____________________ Date Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. Hite M.Sc., University of Kentucky Rudolph P. Byrd, Ph.D. An abstract of A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Emory University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts 2009 Abstract Sisters, Rivals, and Citizens: Venus and Serena Williams as a Case Study of American Identity By Michelle S. -

Florida Women's Tennis

2013-14 Gators (back row, left-to-right): Head Coach Roland Thornqvist, Brianna Morgan, Kourtney Keegan, Stefani Stojic, Belinda Woolcock and Associate Head Coach Dave Balogh; (front row) Program Coordinator Kate Harte, Olivia Janowicz, Sofie Oyen, Alexandra Cercone and Graduate Assistant Athletic Trainer Kelly Needs FLORIDA WOMEN’S TENNIS 2013-14 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT FLORIDA WOMEN’S TENNIS 2013-14 MEDIA SUPPLEMENT CONTENTS / QUICK FACTS 2013-14 SEASON PREVIEW 2013-14 Gator Roster ......................................................3 FLORIDA TENNIS QUICK FACTS (as of Jan. 1, 2014) 2013-14 Gator Schedule ..................................................2 Perry Indoor Facility ........................................................93 G eneral Information SEC Academic Honor Roll (5): .... Alexandra Cercone, Lauren Embree, Caroline Hitimana, Olivia Janowicz, Sofie Oyen Ring Tennis Complex ......................................................91 Location: ......................... Gainesville, Florida UF Quick Facts ................................................................1 SEC Freshman Academic Honor Roll (1): .....Brianna Morgan Est. Population: .............................124,491 ITA Scholar-Athlete (min. 3.5 GPA): ...... Alexandra Cercone MEDIA INFORMATION Founded: ....................................1853 ITA All-Academic Team (minimum 3.2 team GPA): .......yes! Communications Directory, UF ..........................................4 Enrollment: ................................49,785 Directions to Tennis Complex ............................................6 -

Media Guide Template

MOST CHAMPIONSHIP TITLES T O Following are the records for championships achieved in all of the five major events constituting U R I N the U.S. championships since 1881. (Active players are in bold.) N F A O M E MOST TOTAL TITLES, ALL EVENTS N T MEN Name No. Years (first to last title) 1. Bill Tilden 16 1913-29 F G A 2. Richard Sears 13 1881-87 R C O I L T3. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 U I T N T3. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 Y D & T3. Neale Fraser 8 1957-60 S T3. Billy Talbert 8 1942-48 T3. George M. Lott Jr. 8 1928-34 T8. Jack Kramer 7 1940-47 T8. Vincent Richards 7 1918-26 T8. Bill Larned 7 1901-11 A E C V T T8. Holcombe Ward 7 1899-1906 E I N V T I T S I OPEN ERA E & T1. Bob Bryan 8 2003-12 S T1. John McEnroe 8 1979-89 T3. Todd Woodbridge 6 1990-2003 T3. Jimmy Connors 6 1974-83 T5. Roger Federer 5 2004-08 T5. Max Mirnyi 5 1998-2013 H I T5. Pete Sampras 5 1990-2002 S T T5. Marty Riessen 5 1969-80 O R Y C H A P M A P S I T O N S R S E T C A O T I R S D T I S C S & R P E L C A O Y R E D R Bill Tilden John McEnroe S * All Open Era records include only titles won in 1968 and beyond 169 WOMEN Name No. -

The Art of Lawn Tennis

.;.;' .- H41m -^nra usnffl«iHHnBnHmn HIHiSB lilll Hi iwi HH IHHHRhu MB __ EsyHNHRHQBS&F mmHHHHBn^^SP mm mwHw HlHiUliH Milffliilii.ror»» MIBBiiili HHHlllliil Class Book CopigM . COHRIGHT deposit THE ART OF LAWN TENNIS WILLIAM T. TILDEN KfSO PLATE I WILLIAM T. TILDE M- Champion of the world, in action. THE ART OF LAWN TENNIS BY WILLIAM TrTILDEN %» CHAMPION OF THE WORLD WITH THIBTY ILLUSTRATIONS NEW Xlir YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA APR -I 1921 _ ©CLA611413 « To E. D. K AND M. W. J. MY "BUDDIES" W. T. T. n INTRODUCTION Tennis is at once an art and a science. The game as played by such men as Norman E. Brookes, the late Anthony Wilding, William M. Johnston, and R. N. Williams is art. Yet like all true art, it has its basis in scientific methods that must be learned and learned thoroughly for a foundation before the artistic structure of a great tennis game can be con- structed. Every player who helps to attain a high degree of efficiency should have a clearly defined method of development and adhere to it. He should be certain that it is based on sound principles and, once assured of that, follow it, even though his progress seems slow and discouraging. I began tennis wrong. My strokes were wrong and my viewpoint clouded. I had no early training such as many of our American boys have at the pres- ent time. No one told me the importance of the fundamentals of the game, such as keeping the eye on the ball or correct body position and footwork. -

Nadal Revs for Roddick

53 OPINIONS 100 2004 U.S. OPEN BE OUR GUEST By ANDREW FRIEDMAN A very tough sell Scaffold law works – don’t Justine salutes Israeli Wooing voters isn’t easy for black GOPers BLACK ONLY he most elegant folk you ers to the GOP. undermine it Obziler shows some Zip ever saw were clinking Despite his minstrel-show Twine glasses at a swank re- clowning in and around Madi- Contractors want to cut ception of the National Black Re- son Square Garden, King re- publican Council, held yester- mains what the black communi- corners on worker safety in 2nd-round loss to No. 1 day at the Central Park Boat- ty always has known him to be: house. To this group falls the a career criminal from Ohio ast weekend, one immigrant By WAYNE COFFEY thankless task of selling the Re- who has been convicted of kill- died in Brooklyn and anoth- DAILY NEWS SPORTS WRITER ing two men and who served L er was injured — both just publican Party to a black com- A 31-YEAR-OLD VETERAN of the Israeli Army took Center Court munity in which 9 of every 10 years in prison for his offenses. doing their jobs. They worked in voters are almost certain to vote King swindled astring of construction, and their accidents at the U.S. Open yesterday, a Flushing Meadows rookie unlike any Democratic. black boxers and virtually happened on scaffolding at the other. She wore an outfit that was the color of a school bus, Black Republicans come in ruined the sport. -

26279 HON. JIM Mcdermott HON. SCOTT GARRETT

October 2, 2007 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 153, Pt. 19 26279 throughout America, Gibson made history tress Phylicia Rashad (first to win a Tony vertising services to numerous political cam- once again—this time in magnificent fash- for best performance in a play), Essence paigns, voter initiatives, and labor unions. ion—by winning the 1956 French Open to be- chairwoman Susan L. Taylor (first recipient Walt also wrote articles for the Seattle come the first Black to win a Grand Slam of the Henry Johnson Fisher award), and Weekly and was brought further into the event. The next year, she won Wimbledon businesswoman Sheila Crump Johnson (first public eye when he was hired to conduct bi- and the U.S. Championships, then success- to have a stake in three professional sports weekly ‘‘Point-Counterpoint’’ debates with fully defended both titles the following year. franchises). conservative activist John Carlson on KIRO- Gibson teamed with Angela Buxton, a Jewish ‘‘Althea Gibson dreamed the impossible TV News. player from Briton, to win the 1956 doubles and made it possible,’’ said Johnson, who But it was the history muse that inspired championships at the French and was a BET founder. ‘‘She was one of the first Walt’s greatest creative output. His intro- Wimbledon. Both women experienced dis- African-American women in sports to say, duction to historical research came when he crimination by their fellow players, but after ‘Why not me?’ She empowered generations was hired to write a history of the Rainier their triumph at the All-England tennis [of Black women] to believe in themselves, Club. -

Mixed Doubles

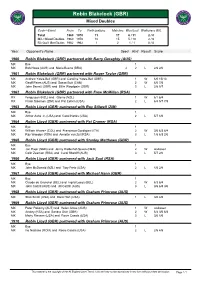

Robin Blakelock (GBR) Mixed Doubles Code->Event From To Participations Matches Won/Lost Walkovers W/L Total 1960 1970 11 17 6 / 11 2 / 0 MX->Mixed Doubles 1960 1970 10 15 5 / 10 2 / 0 RX->Qualif. Mixed Doubles 1962 1962 1 2 1 / 1 0 / 0 Year Opponent's Name Seed Rnd Result Score 1960 Robin Blakelock (GBR) partnered with Barry Geraghty (AUS) MX Bye 1 MX Bob Howe (AUS) and Maria Bueno (BRA) 2 2 L 2/6 2/6 1961 Robin Blakelock (GBR) partnered with Roger Taylor (GBR) MX Andrew Yates-Bell (GBR) and Caroline Yates-Bell (GBR) 1 W 6/0 15/13 MX Geoff Pares (AUS) and Susan Butt (CAN) 2 W 6/0 7/5 MX John Barrett (GBR) and Billie Woodgate (GBR) 3 L 2/6 5/7 1962 Robin Blakelock (GBR) partnered with Frew McMillan (RSA) RX Fergusson (NZL) and Glenie (NZL) 1 W 6/1 6/4 RX Frank Salomon (ZIM) and Pat Edrich (USA) 2 L 6/4 5/7 7/9 1963 Robin Lloyd (GBR) partnered with Roy Stilwell (ZIM) MX Bye 1 MX Arthur Ashe Jr. (USA) and Carol Hanks (USA) 2 L 5/7 1/6 1964 Robin Lloyd (GBR) partnered with Pat Cramer (RSA) MX Bye 1 MX William Alvarez (COL) and Francesca Gordigiani (ITA) 2 W 3/6 6/3 6/4 MX Ray Weedon (RSA) and Annette van Zyl (RSA) 3 L 1/6 6/3 2/6 1965 Robin Lloyd (GBR) partnered with Stanley Matthews (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Jan Hajer (NED) and Jenny Ridderhof-Seven (NED) 2 W walkover MX Colin Zeeman (RSA) and Carol Sherriff (AUS) 3 L 5/7 2/6 1966 Robin Lloyd (GBR) partnered with Jack Saul (RSA) MX Bye 1 MX John McDonald (NZL) and Tory Fretz (USA) 2 L 4/6 2/6 1967 Robin Lloyd (GBR) partnered with Michael Hann (GBR) MX Bye 1 MX Claude de Gronckel (BEL) and Ingrid -

AEGON Championships ORDER of PLAY Thursday, 14 June 2012

AEGON Championships ORDER OF PLAY Thursday, 14 June 2012 CENTRE COURT 1 COURT 2 COURT 9 Matches Start At: 12:30 pm Matches Start At: 12:30 pm Matches Start At: 12:30 pm Matches Start At: 12:30 pm Colin FLEMING (GBR) Robert LINDSTEDT (SWE) Nicolas MAHUT (FRA) Kevin ANDERSON (RSA) [9] Ross HUTCHINS (GBR) [6] Horia TECAU (ROU) [4] 1 vs vs vs vs Grigor DIMITROV (BUL) Feliciano LOPEZ (ESP) [5] [Alt] Steve DARCIS (BEL) Jonathan ERLICH (ISR) Olivier ROCHUS (BEL) Andy RAM (ISR) followed by followed by followed by followed by Marcos BAGHDATIS (CYP) Ivan DODIG (CRO) Julien BENNETEAU (FRA) [8] Jamie MURRAY (GBR) Simone BOLELLI (ITA) 2 vs vs vs vs Jo-Wilfried TSONGA (FRA) [2] Sam QUERREY (USA) Mahesh BHUPATHI (IND) Xavier MALISSE (BEL) Rohan BOPANNA (IND) [5] followed by followed by followed by followed by After suitable rest Kevin ANDERSON (RSA) Ivo KARLOVIC (CRO) Yen-Hsun LU (TPE) Marin CILIC (CRO) [6] Leander PAES (IND) Frank MOSER (GER) 3 vs vs vs vs Janko TIPSAREVIC (SRB) [3] Lukas ROSOL (CZE) Julien BENNETEAU (FRA) Eric BUTORAC (USA) Nicolas MAHUT (FRA) Paul HANLEY (AUS) [8] followed by followed by followed by Alex BOGOMOLOV JR. (RUS) Xavier MALISSE (BEL) David NALBANDIAN (ARG) [10] James CERRETANI (USA) Dick NORMAN (BEL) 4 vs vs vs Edouard ROGER-VASSELIN (FRA) Bob BRYAN (USA) Mariusz FYRSTENBERG (POL) Mike BRYAN (USA) [2] Marcin MATKOWSKI (POL) [3] followed by followed by TBA Max MIRNYI (BLR) Janko TIPSAREVIC (SRB) Daniel NESTOR (CAN) [1] Nenad ZIMONJIC (SRB) [7] 5 vs vs [WC] Lleyton HEWITT (AUS) Kevin ANDERSON (RSA)/Leander PAES (IND) or Andy RODDICK (USA) Julien BENNETEAU (FRA)/Nicolas MAHUT (FRA) Chris Kermode Konstantin Haerle/Miro Bratoev Jimmy Moore Mark Darby/Tom Barnes Tournament Director Tour Manager Referee ATP Supervisor Order of Play released : 13 June 2012 at 21:14 MATCHES WILL BE CALLED ANY MATCH ON ANY COURT Doubles Alternate Sign-in Deadline : 12:00 noon FROM THE PLAYERS' LOUNGE & MAY BE MOVED LOCKER-ROOM.