The Trade in Native and Exotic Turtles in Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geographic Variation in the Matamata Turtle, Chelus Fimbriatus, with Observations on Its Shell Morphology and Morphometry

n*entilkilt ilil Biok,gr', 1995. l(-l):19: 1995 by CheloninD Research Foundltion Geographic Variation in the Matamata Turtle, Chelus fimbriatus, with Observations on its Shell Morphology and Morphometry MlncBLo R. SANcnnz-Vu,urcnAr, PnrER C.H. PnrrcHARD:, ArrnEro P.rorrLLo-r, aNn Onan J. LINlnBs3 tDepartment of Biological Anthropolog-,- and Anatomy, Duke lJniversin' Medical Cetter. Box 3170, Dtu'hcun, North Carolina277l0 USA IFat 919-684-8034]; 2Florida Audubotr Societ-t, 460 High,n;a,- 436, Suite 200, Casselberry, Florida 32707 USA: iDepartanento de Esttdios Anbientales, llniyersitlad Sinzrin Bolltnt", Caracas ]O80-A, APDO 89OOO l/enerte\a Ansrucr. - A sample of 126 specimens of Chelusftmbriatus was examined for geographic variation and morphology of the shell. A high degree of variation was found in the plastral formula and in the shape and size of the intergular scute. This study suggests that the Amazon population of matamatas is different from the Orinoco population in the following characters: shape ofthe carapace, plastral pigmentation, and coloration on the underside of the neck. Additionatly, a preliminary analysis indicates that the two populations could be separated on the basis of the allometric growth of the carapace in relation to the plastron. Kry Wonus. - Reptilia; Testudinesl Chelidae; Chelus fimbriatus; turtle; geographic variationl allometryl sexual dimorphism; morphology; morphometryl osteology; South America 'Ihe matamata turtle (Chelus fimbricttus) inhabits the scute morpholo..ey. Measured characters (in all cases straight- Amazon, Oyapoque. Essequibo. and Orinoco river systems line) were: maximum carapace len.-uth (CL). cArapace width of northern South America (Iverson. 1986). Despite a mod- at the ler,'el of the sixth marginal scute (CW). -

Buhlmann Etal 2009.Pdf

Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 2009, 8(2): 116–149 g 2009 Chelonian Research Foundation A Global Analysis of Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Distributions with Identification of Priority Conservation Areas 1 2 3 KURT A. BUHLMANN ,THOMAS S.B. AKRE ,JOHN B. IVERSON , 1,4 5 6 DENO KARAPATAKIS ,RUSSELL A. MITTERMEIER ,ARTHUR GEORGES , 7 5 1 ANDERS G.J. RHODIN ,PETER PAUL VAN DIJK , AND J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS 1University of Georgia, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Drawer E, Aiken, South Carolina 29802 USA [[email protected]; [email protected]]; 2Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Longwood University, 201 High Street, Farmville, Virginia 23909 USA [[email protected]]; 3Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana 47374 USA [[email protected]]; 4Savannah River National Laboratory, Savannah River Site, Building 773-42A, Aiken, South Carolina 29802 USA [[email protected]]; 5Conservation International, 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500, Arlington, Virginia 22202 USA [[email protected]; [email protected]]; 6Institute for Applied Ecology Research Group, University of Canberra, Australian Capitol Territory 2601, Canberra, Australia [[email protected]]; 7Chelonian Research Foundation, 168 Goodrich Street, Lunenburg, Massachusetts 01462 USA [[email protected]] ABSTRACT. – There are currently ca. 317 recognized species of turtles and tortoises in the world. Of those that have been assessed on the IUCN Red List, 63% are considered threatened, and 10% are critically endangered, with ca. 42% of all known turtle species threatened. Without directed strategic conservation planning, a significant portion of turtle diversity could be lost over the next century. Toward that conservation effort, we compiled museum and literature occurrence records for all of the world’s tortoises and freshwater turtle species to determine their distributions and identify priority regions for conservation. -

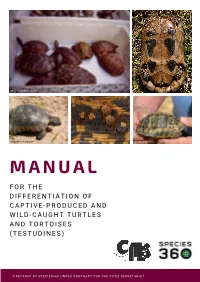

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Demographic Consequences of Superabundance in Krefft's River

i The comparative ecology of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii in Tropical North Queensland. By Dane F. Trembath B.Sc. (Zoology) Applied Ecology Research Group University of Canberra ACT, 2601 Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Applied Science (Resource Management). August 2005. ii Abstract An ecological study was undertaken on four populations of Krefft’s River Turtle Emydura krefftii inhabiting the Townsville Area of Tropical North Queensland. Two sites were located in the Ross River, which runs through the urban areas of Townsville, and two sites were in rural areas at Alligator Creek and Stuart Creek (known as the Townsville Creeks). Earlier studies of the populations in Ross River had determined that the turtles existed at an exceptionally high density, that is, they were superabundant, and so the Townsville Creek sites were chosen as low abundance sites for comparison. The first aim of this study was to determine if there had been any demographic consequences caused by the abundance of turtle populations of the Ross River. Secondly, the project aimed to determine if the impoundments in the Ross River had affected the freshwater turtle fauna. Specifically this study aimed to determine if there were any difference between the growth, size at maturity, sexual dimorphism, size distribution, and diet of Emydura krefftii inhabiting two very different populations. A mark-recapture program estimated the turtle population sizes at between 490 and 5350 turtles per hectare. Most populations exhibited a predominant female sex-bias over the sampling period. Growth rates were rapid in juveniles but slowed once sexual maturity was attained; in males, growth basically stopped at maturity, but in females, growth continued post-maturity, although at a slower rate. -

Can Unwanted Suburban Tortoises Rescue Native Hawaiian Plants?

CAN UNWANTED SUBURBAN TORTOISES RESCUE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS? by David A. Burney, James O. Juvik, Lida Pigott Burney, and Tomas Diagne 104 THE TORTOISE ・ 2012 hrough a series of coincidences, surplus pet tortoises in Hawaii may end up offering a partial solution to the seemingly insurmountable challenge posed by invasive plants in the Makauwahi Cave Reserve Ton Kaua`i. This has come about through a serendipitous intersection of events in Africa, the Mascarene Islands, North America, and Hawaii. The remote Hawaiian Islands were beyond the reach of naturally dispersing island tortoises, but the niches were apparently still there. Giant flightless ducks and geese evolved on these islands with tortoise-like beaks and other adaptations as terrestrial “meso-herbivores.” Dating of these remarkable fossil remains shows that they went extinct soon after the arrival of Polynesians at the beginning of the last millennium leaving the niches for large native herbivores entirely empty. Other native birds, including important plant pollinators, and some plant species have also suffered extinction in recent centuries. This trend accelerated after European settlement ecosystem services and a complex mix of often with the introduction of many invasive alien plants conflicting stakeholder interests clearly requires and the establishment of feral ungulate populations new paradigms and new tools. such as sheep, goats, cattle, and European swine, as Lacking any native mammalian herbivores, the well as other insidious invasives such as deer, rats, majority of the over 1,000 native Hawaiian plant mongoose, feral house cats, and even mosquitoes, species on the islands have been widely regarded which transmit avian malaria to a poorly resistant in the literature as singularly lacking in defensive native avifauna. -

(Geochelone Pardalis) on Farmland in the Nama-Karoo

THE STATUS AND ECOLOGY OF THE LEOPARD TORTOISE (GEOCHELONE PARDALIS) ON FARMLAND IN THE NAMA-KAROO MEGAN KAY McMASTER Submitted in fulfilment ofthe academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE School ofBotany and Zoology University ofNatal Pieterrnaritzburg March 2001 Preface The experimental work described in this dissertation was carried out in the School of Botany and Zoology, University ofNatal, Pietermaritzburg, from November 1997 to March 2001, under the supervision ofDr. Colleen T. Downs. This study is the original work ofthe author and has not been submitted in any form for any diploma or degree to another university. Where use has been made ofthe work of others, it is duly acknowledged in the text. Each chapter is written in the format ofthe journal it has been submitted to. ..fj~K'. Megan Kay McMaster Pietermaritzburg March 2001 11 This thesis is dedicated to myfather, the late Eric Ralph McMaster, for his constant encouragement and beliefin me, and to my brother, the late Gregory CIifton McMaster,for always making me smile. III Abstract The Family Testudinidae (Suborder Cryptodira) is represented by 40 species worldwide and reaches its greatest diversity in southern Africa, where 14 species occur (33%), ten of which are endemic to the subcontinent. Despite the strong representation ofterrestrial tortoise species in southern Africa, and the importance ofthe Karoo as a centre of endemism ofthese tortoise species, there is a paucity ofecological information for most tortoise species in South Africa. With chelonians being protected in < 15% ofall southern African reserves it is necessary to find out more about the ecological requirements, status, population dynamics and threats faced by South African tortoise species to enable the formulation ofeffective conservation measures. -

Recent Evolutionary History of the Australian Freshwater Turtles Chelodina Expansa and Chelodina Longicollis

Recent evolutionary history of the Australian freshwater turtles Chelodina expansa and Chelodina longicollis. by Kate Meredith Hodges B.Sc. (Hons) ANU, 2004 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences Department of Genetics and Evolution The University of Adelaide December, 2015 Kate Hodges with Chelodina (Macrochelodina) expansa from upper River Murray. Photo by David Thorpe, Border Mail. i Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library catalogue and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. -

Status Review, Disease Risk Analysis and Conservation Action Plan for The

Status Review, Disease Risk Analysis and Conservation Action Plan for the Bellinger River Snapping Turtle (Myuchelys georgesi) December, 2016 1 Workshop participants. Back row (l to r): Ricky Spencer, Bruce Chessman, Kristen Petrov, Caroline Lees, Gerald Kuchling, Jane Hall, Gerry McGilvray, Shane Ruming, Karrie Rose, Larry Vogelnest, Arthur Georges; Front row (l to r) Michael McFadden, Adam Skidmore, Sam Gilchrist, Bruno Ferronato, Richard Jakob-Hoff © Copyright 2017 CBSG IUCN encourages meetings, workshops and other fora for the consideration and analysis of issues related to conservation, and believes that reports of these meetings are most useful when broadly disseminated. The opinions and views expressed by the authors may not necessarily reflect the formal policies of IUCN, its Commissions, its Secretariat or its members. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Jakob-Hoff, R. Lees C. M., McGilvray G, Ruming S, Chessman B, Gilchrist S, Rose K, Spencer R, Hall J (Eds) (2017). Status Review, Disease Risk Analysis and Conservation Action Plan for the Bellinger River Snapping Turtle. IUCN SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Cover photo: Juvenile Bellinger River Snapping Turtle © 2016 Brett Vercoe This report can be downloaded from the CBSG website: www.cbsg.org. 2 Executive Summary The Bellinger River Snapping Turtle (BRST) (Myuchelys georgesi) is a freshwater turtle endemic to a 60 km stretch of the Bellinger River, and possibly a portion of the nearby Kalang River in coastal north eastern New South Wales (NSW). -

A Sulcata Here, a Sulcata There, a Sulcata Everywhere Text and Photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter

A Sulcata Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) emerging from a burrow in its enclosure. of the African Spurred Tortoise (Geochelone sulcata) A Sulcata Here, A Sulcata There, A Sulcata Everywhere text and photography by Dave Friend, President, CTTC, Santa Barbara-Ventura Chapter n 1986 my wife and I fell in The breeder said to feed them pumpkin All the stucco along the side of the house love with the Sulcata Tor- and alfalfa. There was not a lot of diet infor- as far as they could ram was broken. The toise and decided to purchase mation available then. We did not have good male more than the female did the greater a pair. Yes, purchase. Twenty-three years luck with the breeder’s diet. They preferred damage. Our youngest son had the outside ago there were not many Sulcatas available. the Bermuda grass, rose petals and hibis- corner bedroom upstairs, every night after We found a “BREEDER” in Riverside, CA. cus flowers in the back yard. We gave them he would go to bed I could here him holler- Made the contact and brought the pair home other treats once in a while: apples, squash, ing at that %#@* turtle. The Sulcata would toI Ventura, CA. So began an adventure that and other vegetables. Pumpkin never was start ramming the side of the house. I would we still enjoy today. high on their list of treats! They also loved to go down and move him, put things in his We were told they were about seven years drink from a running hose laid on the lawn. -

Resolving the Phylogenetic History of the Short-Necked Turtles, Genera

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 68 (2013) 251–258 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Resolving the phylogenetic history of the short-necked turtles, genera Elseya and Myuchelys (Testudines: Chelidae) from Australia and New Guinea ⇑ Minh Le a,b,c, , Brendan N. Reid d, William P. McCord e, Eugenia Naro-Maciel f, Christopher J. Raxworthy c, George Amato g, Arthur Georges h a Department of Environmental Ecology, Faculty of Environmental Science, Hanoi University of Science, VNU, 334 Nguyen Trai Road, Thanh Xuan District, Hanoi, Viet Nam b Centre for Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, VNU, 19 Le Thanh Tong Street, Hanoi, Viet Nam c Department of Herpetology, Division of Vertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA d Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA e East Fishkill Animal Hospital, 455 Route 82, Hopewell Junction, NY 12533, USA f Biology Department, College of Staten Island, City University of New York, Staten Island, NY 10314, USA g Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA h Institute for Applied Ecology, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia article info abstract Article history: Phylogenetic relationships and taxonomy of the short-necked turtles of the genera Elseya, Myuchelys, and Received 15 October 2012 Emydura in Australia and New Guinea have long been debated as a result of conflicting hypotheses sup- Revised 14 March 2013 ported by different data sets and phylogenetic analyses. To resolve this contentious issue, we analyzed Accepted 24 March 2013 sequences from two mitochondrial genes (cytochrome b and ND4) and one nuclear intron gene (R35) from Available online 4 April 2013 all species of the genera Elseya, Myuchelys, Emydura, and their relatives. -

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29