Background Meta and Vichada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meta River Report Card

Meta River 2016 Report Card c Casanare b Lower Meta Tame CASANARE RIVER Cravo Norte Hato Corozal Puerto Carreño d+ Upper Meta Paz de Ariporo Pore La Primavera Yopal Aguazul c Middle Meta Garagoa Maní META RIVER Villanueva Villavicencio Puerto Gaitán c+ Meta Manacacías Puerto López MANACACÍAS RIVER Human nutrition Mining in sensitive ecosystems Characteristics of the MAN & AG LE GOV E P RE ER M O TU N E E L A N P U N RI C T Meta River Basin C TA V / E ER E M B Water The Meta River originates in the Andes and is the largest I O quality index sub-basin of the Colombian portion of the Orinoco River D I R V E (1,250 km long and 10,673,344 ha in area). Due to its size E B C T R A H A Risks to S S T and varied land-uses, the Meta sub-basin has been split I I L W T N HEA water into five reporting regions for this assessment, the Upper River Y quality EC S dolphins & OSY TEM L S S Water supply Meta, Meta Manacacías, Middle Meta, Casanare and Lower ANDSCAPE Meta. The basin includes many ecosystem types such as & demand Ecosystem the Páramo, Andean forests, flooded savannas, and flooded Fire frequency services forests. Main threats to the sub-basin are from livestock expansion, pollution by urban areas and by the oil and gas Natural industry, natural habitat loss by mining and agro-industry, and land cover Terrestrial growing conflict between different sectors for water supply. -

Analysis of Streamflow Variability and Trends in the Meta River, Colombia

water Article Analysis of Streamflow Variability and Trends in the Meta River, Colombia Marco Arrieta-Castro 1, Adriana Donado-Rodríguez 1, Guillermo J. Acuña 2,3,* , Fausto A. Canales 1,* , Ramesh S. V. Teegavarapu 4 and Bartosz Ka´zmierczak 5 1 Department of Civil and Environmental, Universidad de la Costa, Calle 58 #55-66, Barranquilla 080002, Atlántico, Colombia; [email protected] (M.A.-C.); [email protected] (A.D.-R.) 2 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Instituto de Estudios Hidráulicos y Ambientales, Universidad del Norte, Km.5 Vía Puerto Colombia, Barranquilla 081007, Colombia 3 Programa de Ingeniería Ambiental, Universidad Sergio Arboleda, Escuela de Ciencias Exactas e Ingeniería (ECEI), Calle 74 #14-14, Bogotá D.C. 110221, Colombia 4 Department of Civil, Environmental and Geomatics Engineering, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Systems, Faculty of Environmental Engineering, Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, 50-370 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (F.A.C.); [email protected] (G.J.A.); Tel.: +57-5-3362252 (F.A.C.) Received: 29 March 2020; Accepted: 13 May 2020; Published: 20 May 2020 Abstract: The aim of this research is the detection and analysis of existing trends in the Meta River, Colombia, based on the streamflow records from seven gauging stations in its main course, for the period between June 1983 to July 2019. The Meta River is one of the principal branches of the Orinoco River, and it has a high environmental and economic value for this South American country. -

Asis) Vichada (Puerto Carreño, La Primavera Y Cumaribo

ANALISIS DE LA SITUACIÒN DE SALUD FRONTERIZO (ASIS) Secretaria Seccional de Salud DEL VICHADA. ANALISIS DE LA SITUACION DE SALUD DE FRONTERAS (ASIS) VICHADA (PUERTO CARREÑO, LA PRIMAVERA Y CUMARIBO) ELABORADO POR: JANETH CRISTINA ACEVEDO JAIMES EPIDEMIOLOGA SSSV JUNIO de 2012 1 ANALISIS DE LA SITUACIÒN DE SALUD FRONTERIZO (ASIS) Secretaria Seccional de Salud DEL VICHADA. PUNTOS FOCALES NACIONALES Y DEPARTAMENTALES PARTICIPANTES EN LA RECOLECCION, ANALISIS Y LA REDACCION DEL ASIS (VICHADA 2010) Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social Secretaria Seccional de Salud Dra. Iliana Martínez Hernández Dirección de Epidemiología y Demografía Dr. Juan Carlos Romero Bossa Convenio 485/10-OPS/MSMP Secretario Seccional de Salud Grupo Fronteras Jefe. Luz Helena Trujillo Dra. Luz Stella Ríos Marín Coordinadora Salud Pública Dirección de Epidemiología y Demografía Convenio 485/10-OPS/MSMP Dr. Francy Bermúdez Grupo Fronteras Secretaria de Planeación Secretaria de Planeación Departamental Jefe. Consuelo Sierra Coordinadora PAI Departamental Ing. Julio Cesar Flórez Orjuela Secretario de Planeación y Desarrollo Dra. Aide Devia Territorial Epidemióloga Secretaria de Educación Ing. Luis Chávez Sistemas de Información Dr. Luis Samuel Rodríguez Secretario de Educación Departamental Unidad Básica de Atención Nuestra Señora del Carmen Secretaria de Asuntos Indígenas Dr. Humberto Moreno Giraldo Dra. Nancy Mattar Gerente Interventor UBA Secretaria de Asuntos Indígenas Departamental 2 ANALISIS DE LA SITUACIÒN DE SALUD FRONTERIZO (ASIS) Secretaria Seccional de Salud DEL VICHADA. AGRADECIMIENTOS No habría sido posible elaborar este documento sin la valiosa colaboración de un grupo interdisciplinario a nivel departamental, sin embargo, resaltó el apoyo incondicional de la Doctora Iliana Martínez sin la cual no hubiera sido posible iniciar y culminar esta ardua labor. -

Cartografía Geológica Y Muestreo Geoquímico De Las Planchas 201 Bis, 201, 200 Y 199 Departamento De Vichada”

SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO COLOMBIANO “CARTOGRAFÍA GEOLÓGICA Y MUESTREO GEOQUÍMICO DE LAS PLANCHAS 201 BIS, 201, 200 Y 199 DEPARTAMENTO DE VICHADA” MEMORIA EXPLICATIVA Bogotá D.C., marzo de 2013 República de Colombia MINISTERIO DE MINAS Y ENERGÍA SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO COLOMBIANO REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA MINISTERIO DE MINAS Y ENERGÍA SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO COLOMBIANO PROYECTO SUBDIRECCIÓN DE CARTOGRAFIA BASICA “CARTOGRAFIA GEOLOGICA Y MUESTREO GEOQUIMICO DE LAS PLANCHAS 201 BIS, 201, 200 Y 199 DEPARTAMENTO DE VICHADA” MEMORIA EXPLICATIVA Por: Alberto Ochoa Y. Ing. Geólogo – Coordinador del Proyecto Geóloga Paula A. Ríos B. Geóloga Ana M. Cardozo O. Geóloga Juanita Rodríguez M. Geólogo Jorge A. Oviedo R. Geólogo Gersom D. García. Ingeniero Geólogo José V. Cubides T. Bogotá D. C., marzo de 2013 SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO COLOMBIANO CONTENIDO Pág. CONTENIDO ...................................................................................................... 2 LISTA DE FIGURAS .......................................................................................... 7 LISTA DE TABLAS ......................................................................................... 13 LISTA DE ANEXOS ......................................................................................... 15 RESUMEN…… ................................................................................................ 16 ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................... 20 1. GENERALIDADES ...................................................................... -

Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the Pan-Amazon Region

OAS/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 176 29 September 2019 Original: Spanish INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Situation of Human Rights of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the Pan-Amazon Region 2019 iachr.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Situation of human rights of the indigenous and tribal peoples of the Pan-Amazon region : Approved by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on September 29, 2019. p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.L/V/II) ISBN 978-0-8270-6931-2 1. Indigenous peoples--Civil rights--Amazon River Region. 2. Indigenous peoples-- Legal status, laws, etc.--Amazon River Region. 3. Human rights--Amazon River Region. I. Title. II. Series. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.176/19 INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Members Esmeralda Arosemena de Troitiño Joel Hernández García Antonia Urrejola Margarette May Macaulay Francisco José Eguiguren Praeli Luis Ernesto Vargas Silva Flávia Piovesan Executive Secretary Paulo Abrão Assistant Executive Secretary for Monitoring, Promotion and Technical Cooperation María Claudia Pulido Assistant Executive Secretary for the Case, Petition and Precautionary Measure System Marisol Blanchard a.i. Chief of Staff of the Executive Secretariat of the IACHR Fernanda Dos Anjos In collaboration with: Soledad García Muñoz, Special Rapporteurship on Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Rights (ESCER) Approved by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on September 29, 2019 INDEX EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 INTRODUCTION 19 CHAPTER 1 | INTER-AMERICAN STANDARDS ON INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES APPLICABLE TO THE PAN-AMAZON REGION 27 A. Inter-American Standards Applicable to Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in the Pan-Amazon Region 29 1. -

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian Tributaries of the Orinoco

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian tributaries of the Orinoco The Orinoco Basin Health Report Card was officially kicked-off in June 2015 with the first stakeholder engagement meeting in Puerto López, in the Orinoquía Region of Meta Department, Colombia. More than 40 representatives from 19 organizations attended the workshop aimed at identifying the environmental, social and economic indicators that will form the basis of the Meta River Report Card. Indicators were chosen based on the top values identified as key to the future sustainability of the Meta River basin. Participating institutions included the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Humboldt Institute, Corporinoquia, Omacha Foundation, Fundacion Orinoco, WWF, among others. The three-day interactive workshop also attracted positive media attention. Outcomes from the meeting included: 1. Identification, and ranking by importance, of environmental, social and economic values within the Meta River basin. 2. Identification, and ranking by importance, of threats to identified values within the Meta River basin. 3. Choice of indicators for measuring/reporting the status of these values and threats. 4. Assignment of key personnel to work on developing each indicator and defining benchmarks for scoring against. ? 5. A time line through to completion and public release in early next 2016. ? Reporting regions The 804 km length of the Meta River traverses a variety of elevations and ecosystem types ? from its origins in the Andes to it’s confluence with the Orinoco River, near Puerto Carreño in the east. Hence, it is anticipated that the river will be divided into three reporting regions, each being assessed and scored independently of each other. -

A New Species of Limatulichthys Isbrücker & Nijssen

Zootaxa 3884 (4): 360–370 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3884.4.5 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:70AC996B-0D18-4F0C-9650-150A58986F2C A new species of Limatulichthys Isbrücker & Nijssen (Loricariidae, Loricariinae) from the western Guiana Shield ALEJANDRO LONDOÑO-BURBANO1,2,3, STÉPHANIE L. LEFEBVRE2,3 & NATHAN K. LUJAN2,3,4 1Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Laboratório de Sistemática de Vertebrados, Avenida Ipiranga 6681, P. O. Box 1429, 90619-900 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Natural History, Royal Ontario Museum, 100 Queen’s Park, Toronto, ON, M5S 2C6, Canada. E-mail: stephanie.lefeb- [email protected], [email protected] 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, 25 Willcocks St., Toronto, ON, M5S 3B2, Canada. 4Current address: Center for Systematic Biology and Evolution, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA 19103, USA. Abstract Limatulichthys nasarcus n. sp. is described as a new species based on 15 specimens from the Ventuari and Caura Rivers in Southern Venezuela. The new species can be distinguished from its only congener, L. griseus, by the presence of ante- rior abdominal plates half the size of those at center of abdomen (vs. plates similar in size); distinct spots less than half of diameter of naris across entire dorsum, including snout and head (vs. indistinct dorsal spots larger or equal than diameter of naris); lateral portions of head and opercle with dark well-defined spots larger than those on dorsum (vs. -

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian Tributaries of the Orinoco

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian tributaries of the Orinoco The Orinoco Basin Health Report Card was officially kicked-off in June 2015 with the first stakeholder engagement meeting in Puerto López, Reporting regions in the Orinoquía Region of Meta Department, Colombia. The 804 km length of the Meta River traverses a More than 40 representatives from 19 organizations attended the variety of elevations and ecosystem types from it’s workshop. During the workshop the environmental, social and origins in the Andes to it’s confluence with the economic indicators that will form the basis of the Meta River Report Orinoco River, near Puerto Carreño in the east. Card were identified. Indicators were chosen based on the top values Hence, it is anticipated that the river will be divided identified as key to the future sustainability of the Meta River basin. into three reporting regions, each being assessed We appreciate the continued active participation of the following and scored independently of each other. organizations with environmental authorities that will enable the completion of the report: the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Preliminary discussions were held on how best to Development, the Von Humboldt Institute, Corporinoquia, Omacha define these regions and it was generally accepted Foundation, National Authority for Aquaculture and Fisheries, the to achieve this based on elevation changes. A Palmita Reserve Foundation, Javeriana University, University of the technical group has been established to define and Llanos, Palmarito Foundation, Ocelot Foundation, Calidris Foundation, document these regions. Foundation Orinoco Biodiversa, Federation National Cattlemen, Corpochivor, Nature Reserve The Pedregoza, Orinoquia Foundation, University of Maryland and WWF. -

9 Conclusion

9 Conclusion 1. The following conclusions have been drawn as a result of considering the objectives set forth for the study: 1.1 This Environmental Impact Study for Forest First’s forestry project in the municipality of Puerto Carreño, Vichada (Colombia), was based on the review of national and regional laws and related social, employment and environmental regulations, as well as on FSC’s Forestry Management Principles and Criteria and ILO’s conventions. 1.2 The base line for the forestry project’s establishment area was defined in accordance with social, environmental and economic factors from the field of forestry. 1.3 The identification attained of the main environmental and social impact (positive and negative) elements derived from forestry activities, and from Forest First´s operational activities has allowed for recommendations by way of prevention, mitigation and compensation measures, and for the formulation of a monitoring and follow-up plan. 1.4 Areas of high conservation value have been identified on the basis of primary and secondary data, leading to the definition of measures for the corresponding handling and monitoring activities implied. 2. The identification, assessment and analysis of the impact of Forest First’s forestry project called for the definition of a base line, given the fact that all information available on the Puerto Carreño municipality and the Vichada Department was dispersed, out of date and/or in bibliographical textbooks of institutions. The result of this task was a set of complete information on the referred municipality, which may be considered a full and up-to-date base for decision-making and planning in the municipality. -

A Surface Water Model for the Orinoco River Basin

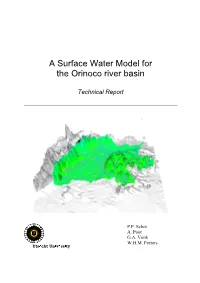

A Surface Water Model for the Orinoco river basin Technical Report P.P. Schot A. Poot G.A. Vonk W.H.M. Peeters 2 A Surface Water Model for the Orinoco river basin Technical Report P.P. Schot A. Poot G.A. Vonk W.H.M. Peeters Utrecht, March 2001 Department of Environmental Sciences Faculty of Geography Utrecht University P.O.Box 80.115 3508 TC Utrecht The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 3 4 Contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. 6 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................... 7 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 9 2 STUDY AREA ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1 General description................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Climate .................................................................................................................. 10 2.3 Hydrology.............................................................................................................. 12 3 GENERAL MODEL DESCRIPTION.......................................................................... 16 3.1 Model concept ....................................................................................................... 16 3.2 Model input .......................................................................................................... -

Guahibo ETHNONYMS: Goahibo, Goahiva, Guaigua, Guajibo, Guayba, “Sicuani”, “Sikuani”, Wahibo By: Alex Menz

Guahibo ETHNONYMS: Goahibo, Goahiva, Guaigua, Guajibo, Guayba, “Sicuani”, “Sikuani”, Wahibo By: Alex Menz 1. Description 1.1 Name of society, language, and language family: Amorua (Rio Tomo Guahibo), Guahibo (Sikuani), Tigrero, Vichadeño. Guahiban languages may not be within Arawakan; Guahibo; Guajiboan/Guajibo. (1) 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): GUH 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): “The Guahibo occupy almost all the Comisari'a of Vichada, Colombia, in a region centered approximately upon 50 north latitude and 680 west longitude. This is a zone bounded by the Meta River on the north, the Vichada River on the south, the Orinoco River on the east, and the Muco River on the west. Outside this area, marginal groups are found north of the Meta, in Boyaca and Arauca, and south of the Vichada, in the vicinity of the Mataveni River. In Venezuela a few have also been reported in the Apure region and south of the Orinoco in Amazonas Territory. The linguistically related Churoyan and Cunimian speakers are located within Colombia to the southwest, in the Department of Meta, along the upper Guaviare River and its affluents. Essentially, the Guahibo form an isolated linguistic unit geographically confined to the Colombian llanos, surrounded by various groups of Carib and Arawak speakers” (5, 16). In Colombia, Plains regions, Casanare, eastern Meta, Vichada, Guaviare, and Guainía departments. Also in Venezuela, Amazonas and Apure states, Orinoco river from Caicaro de Orinoco on the upper Orinoco. (1) “Beginning in the 1950s, some groups migrated toward the east, to the central Orinoco and the jungle areas of the Río Guaviare and to Amazonas in Venezuela” (2, Orientation). -

Annual Report 2019

\ \ / I / ~~ ----- \ I ' ' / CADASTRE, LAND REGISTRY AND MAPPING AGENCY I \ I I I ---~----~ I // \ I / / I / / /--"" \ I / I I \ I -------- -......._ I I I I I I I I I I \ 1 I I \ I I \ '--/ I \ \ \ I I I I / / I ' ,_ ' ' / / \ ' ----- / I I I I I / / --- ~~ ....... / ---- I " '- \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ~~-, \ I I \ I I I I I 1/ \_// / \ / / ' ' / / / ~--- / ----------- / I I ,.....,. ...... I ------------- I / / / / ------ / / / / / / / / / / / / I I I I I I / / ---~ / I I I I I / ' I I / ' \ I \ I ' ' \ I \ I ------- \ I I \ ~- I I \ I I \ I \ I ' I \ ' I \ I I ' I I \ ' ' \ I \ ' I I ' \ \ I \ I I \ / \ I I ' ' I ' ', I ' I \ ' I ' \ I ' \ \ ' \ I ,_ / --------- I ' I ~ / I I TIERRA EN PAZ ' ---- / I I / / I I I I I \ \ I I I ' ----- \ \ \ \ ' ....... _____ _ \ ' ' ' ,_ --~- C--ot.LABORATION COLOMBIA THE NETHERLANDS / \ / ' / ' / 1/ ~/--\ i ANNUAL PROJECT REPORT ' I I I 1 1 / ' \ I I \ I I I \ I \ '--/ I I PERIOD: FEB 2019 - FEB 2020 \ \ '-, /1 I \ I ' ' "' I ' ' / \ ----- / / / I I / I I ~---"' / \ \ / I \ / I / I I \ ' " I \ '----~-- ~--- / I /---- / I /---- ' ~~ 1 ' ' I 1 ' I ,-- " ' " ',, I I ,--._ " I I " \ ------ --- \ " \ ---~---- I I ', \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ) ~-- I / ' -----', \ \ ) I ' '--- I / " '-- I / ' ~~---,"' I "\ I " I / / /' \ I / '- \ " '-, / I / / I I I \ / /--, \ I I I 1 I I I I I --------- ......... ( I \ I I I I I \ ~~ ~~ I I I \ I I \ 1 I I I '- I" I '-,_1 I / I \ \ I ----- I \ / I I I I \ I \ I I " / I \ / I '-, ' / " --~-- / ', I \ I / , '- __ I / \ I \ I ~------ " I -- ---- " I " ' / ' / ----------- / ', ~~ '-, ) I ----- / ----....__ I " I ' \ \ \ \ \ \ I \ \ /--, \ " ------' \ ' \ " ' ' ' I I \ I " I " " \ I I I Colophon /'----, I ' / I \ I I " \ I I I I / " " / I ' I ' ' / \ ---- / ----- '----/ / / / " ' / / / ----------- ~~ This is the yearly report (February 2019 - February 2020) of ~ '-, / / ------ / -------------- the Land in Peace Project, a Colombian-Dutch collaboration / / / concerning land administration financed by the Netherlands ------- / / as support to the implementation of the Colombian Peace / / / Agreement.