The Notion of the Vanishing of Regret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skim Or 1% Milk Gallons

Lenten Seafood Specials See Page 3.. ® Skim or 1% Save 60¢ Milk Gallons ® No Artificial rBST Excellent Source 99Not Valid In The State Growth Hormones Of Calcium Of Maine. SEAFOOD Wild • All Natural 1 Ocean Fresh Swordfish Fresh Veal Cutlets Steaks Thin Sliced Cut Save $1.00lb. Fresh Hand Trimmed Daily Instore $ 99 99 Save 4.50lb. 10 lb. lb. DELI ® Provolone 7 Brown Sorrento or Is Now Sugar Galbani Mozzarella Ham Cheese Save$1.00lb. Save $1.50lb. Sliced Fresh 99 99 At The Deli 3 lb. lb. A Good Source 2 PRODUCE Of Vitamins A,C Florida & Iron Tender 2-LB. Sweet Fresh Green CONT. Asparagus Strawberries Save 70¢ Pasta Save$1.00lb. Save$4.98 •Tortellini 99 99 •Ravioli 8-12 oz. $ •Gnocchi PKG. 1 lb. 3 2 for4 6 PACK 6 PACK 25 Happy Baby Assorted Cuts •Original •Lemon Poland •Organic •Strawberry •Black Cherry Spring •Orange •Lime Whole Milk •Raspberry Lime Sparkling Yogurt Pasta Water Save $5.76 Sale $ Save$1.25 Save 2.00 $ 10 oz. 4for5 $ 16 PROGRESSO $ 16.9 oz. BTLS. for Varieties 16 oz. PKG. for VEGETABLE 5 5 2 3 ® CLASSICS Hearty Steamfresh SOUPS Corn Breads Save Up To $1.24 Save $5.00 Save $1.00 •Peas •Vegetables With Rice ¢ $ •12 Grain •Hearty Nut $ •Oat Nut •100% Wheat FROZEN 10 oz. PKG. 18.5-19 oz. CAN for •Soft Oatmeal 24 oz. for Happy88 Valentine’s5 5 Day2 3 ™ 4 Inch ™ ™ Stick Balloons ™ ™ ™ % ™ ™ ™ ™ 10 Off ™ ¢ ™ ™ Choose From 4 Styles EACH ™ ™ 99 ™ These Select ™ 18 Inch ™ ™ Standard Size ™ Gift Cards ™ ™ Red or Assorted Colors ™ ™ ONE DOZEN With Baby’s Breath & Greens ™ 99™ ™ Choose From 5 Styles EACH ™ Long ™ 1 ™ ™ BAKERY Valentine ™ ™ Cupcakes ™ Stem ™ ™ 99 •Vanilla •Chocolate ™ ™ Roses ™ ™ The Perfect Valentine Gift While supplies last. -

Milk 101 a Discussion on Dairy Fat

milk 101 a discussion on dairy fat There are many different types of milk sold at the grocery store and one difference between them is the amount of fat they contain. The percentages included in the names of milk indicate how much fat is in the milk by weight. The different varieties match the wide range of consumer preferences. MILK 4% milk (whole milk) has the richest, thickest and creamiest taste. 4% It contains about 160 calories and 9 grams of fat per cup. MILK 2% milk (reduced-fat milk) still has a creamy taste but less so than 2% whole milk. It contains about 125 calories and 5 grams of fat per cup. 1% milk (low-fat milk) has a much less creamy taste and a thinner MILK mouthfeel and appearance. It contains about 100 calories and 2.5 1% grams of fat per cup. Fat-free milk (nonfat or skim milk) has no more than 0.2% milk fat, MILK FAT-FREE resulting in the thinnest mouthfeel and appearance. It contains about 80 calories and less than 1 gram of fat per cup. dairy fat science Research supports that whole-milk dairy is just as healthful as lower-fat options, despite its higher fat content. A recent review of the existing research on whole-milk dairy consumption published in the European Journal of Nutrition found that people who eat full-fat dairy are not more likely to develop cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes than people who stick to low-fat dairy. Additionally, in 11 of the 16 studies included in the review, people who consumed more high-fat dairy products either weighed less or gained less weight over time. -

Mongolica Pragensia ’16 9/2

Mongolica Pragensia ’16 9/2 Mongolica Pragensia ’16 Ethnolinguistics, Sociolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 9, No. 2 Publication of Charles University Faculty of Arts, Department of South and Central Asia Seminar of Mongolian and Tibetan Studies Prague 2016 ISSN 1803–5647 This journal is published as a part of the Programme for the Development of Fields of Study at Charles University, Oriental Studies, sub-programme “The process of transformation in the language and cultural differentness of the countries of South and Central Asia”, a project of the Faculty of Arts, Charles University. The publication of this Issue was supported by the TRITON Publishing House. Mongolica Pragensia ’16 Linguistics, Ethnolinguistics, Religion and Culture Volume 9, No. 2 (2016) © Editors Editors-in-chief: Veronika Kapišovská and Veronika Zikmundová Editorial Board: Daniel Berounský (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) Agata Bareja-Starzyńska (University of Warsaw, Poland) Katia Buffetrille (École pratique des Hautes-Études, Paris, France) J. Lubsangdorji (Charles University Prague, Czech Republic) Marie-Dominique Even (Centre National des Recherches Scientifiques, Paris, France) Veronika Kapišovská (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) Marek Mejor (University of Warsaw, Poland) Tsevel Shagdarsurung (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Domiin Tömörtogoo (National University of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia) Veronika Zikmundová (Charles University in Prague, Czech Republic) English correction: Dr. Mark Corner (HUB University, Brussels) Department of South and Central Asia, Seminar of Mongolian and Tibetan Studies Faculty of Arts, Charles University Celetná 20, 116 42 Praha 1, Czech Republic http://mongolistika.ff.cuni.cz Publisher: Stanislav Juhaňák – TRITON http://www.triton-books.cz Vykáňská 5, 100 00 Praha 10 IČ 18433499 Praha (Prague) 2016 Cover Renata Brtnická Typeset Studio Marvil Printed by Art D – Grafický ateliér Černý s. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

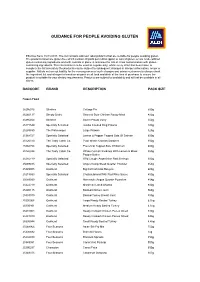

Guidance for People Avoiding Gluten

GUIDANCE FOR PEOPLE AVOIDING GLUTEN Effective from: 15/11/2017. The list contains Aldi own label products that are suitable for people avoiding gluten. The products listed are gluten free which contain 20 parts per million (ppm) or less of gluten, or are made without gluten-containing ingredients and with controls in place to minimise the risk of cross contamination with gluten- containing ingredients. This information is to be used as a guide only; whilst every effort has been taken to complete the list accurately the products may be subject to subsequent changes in allergen information, recipe or supplier. Aldi do not accept liability for the consequences of such changes and advise customers to always check the ingredient list and allergen information on pack on all food and drink at the time of purchase to ensure the product is suitable for your dietary requirements. Products are subject to availability and will not be available in all stores. BARCODE BRAND DESCRIPTION PACK SIZE Frozen Food 25295016 Slimfree Cottage Pie 500g 25260137 Simply Bistro Sweet & Sour Chicken Ready Meal 400g 25295054 Slimfree Sweet Potato Curry 550g 25171549 Specially Selected Jumbo Cooked King Prawns 180g 25288650 The Fishmonger Large Prawns 325g 25368727 Specially Selected Lemon & Pepper Topped Side Of Salmon 600g 25126310 The Tasty Catch Co. Plain Whole Cornish Sardines 350g 25368758 Specially Selected Provencal Topped Side Of Salmon 600g 25126334 The Tasty Catch Co. Whole Cornish Sardines With Lemon & Black 350g Pepper Butter 25282719 Specially Selected -

Gobi Desert & Karakorum Mongolia Land Cruiser Toyota 4X4

Gobi Desert & Karakorum Mongolia Land Cruiser Toyota 4X4 Expedition with Great Naadam Festival in Ulaanbaatar (July 1th-July 13th) Key Information: Trip Length: 13 days/12 nights. Trip Type: Easy to Moderate. Tour Code: SMT-NF1-13D Specialty Categories: Adventure Gobi Desert Expedition, Cultural Event Journey, Camel riding, Driving tour, Local Culture, Nature & Wildlife, and Sports. Meeting/Departure Points: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (excluding the flights). Naadam Festival Special Group Size: 2-9 people or more participants. Hot Season: July 1st-July 13th Total Distance: about +2500kms/1554miles. Airfare Included: No. Tour Customizable: Yes Tour Highlights: Upon your arrival in Ulaanbaatar (ULN or UB), capital of Authentic Mongolia, meet Samar Magic Tours team. Naadam is a traditional type of Festival in Mongolia. The festival is also locally term ed 'the three games of men'. The games are Mongolian wrestling, horse racing and archery and are held throughout the country. The three games of wrestling, horse racing, and archery had been recorded in the 13rd century book The Secret History of the Mongols. It formally commemorates the 1921 Revolution, when Mongolia declared itself independent of China. Women have started participating in the archery and girls in the horse-racing gam es, but not in Mongolian wrestling. The biggest festival is held in the Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar, during the National Holiday from July 11th - July 13th, in the National Sports Stadium. It begins with an elaborate introduction cerem ony featuring dancers, athletes, horse riders, and musicians. After the ceremony, the com petitions begin. Another popular Naadam activity is the playing of games using shagai, sheep knuckles that serve as gam e pieces and tokens of both divination and friendship. -

Ready for a Skyr Game Changer? Ready for a Skyr Game Changer?

INTERNATIONAL May 2020 PROCESSING INGREDIENTS PACKAGING IT LOGISTICS www.international-dairy.com Ready for a skyr game changer? Ready for a skyr game changer? Would you like to produce a skyr with a superior in-mouth experience on your separator processing line? At Arla Foods Ingredients, we have developed Nutrilac® YO-4575 which allows you to produce skyr effi ciently on your separator processing line. Based on natural whey proteins, our tailored ingredient delivers a delicious mouthfeel, texture and taste time aft er time. Editorial ¦ IDM Months are lost World dairy trade will continue to suffer At the moment this commentary is being written, everything revolves around how the world, people and, above all, economy can return to normal life from the rigidity of pandemic con- tainment without causing further damage. A further lockdown, which would undoubtedly be imposed if the infection figures were to flare up again, would in all probability be the death knell for large parts of industry and the economy. But even so, there will be enormous upheavals when the world awakens from isolation. The threat of millions of jobs being lost or already lost will not exactly encourage people to spend money. People will have to economize on consumption and, by force, on every- thing else. In addition, global milk exports will fall, because the oil-producing countries in Roland Sossna particular are short of money due to the drop in oil prices and will be unable to act develop Editor IDM significant demand for the time being. International Dairy Magazine [email protected] Incidentally, milk processors are affected by the pandemic in very different ways. -

Download the Guide

ONTARIO 2021 DAIRY GUIDE ONTARIO DAIRY GUIDE 1 Whether crafted by hand or at scale, Ontario dairy products are all inspired by a single delicious, sustainable and local ingredient: EVERYDAY MILK… DID YOU KNOW? • As a result of continuous investments in sustainability LOCAL MILK WHOLE MILK and production practices, 65% fewer cows produce Barista milk! Whole (3.25% milk fat) milk is lighter than cream but the same volume of milk needed to nourish all of Producing the fresh, local milk that elevates an incredible range of high-quality adds a luxurious smoothness to coffee beverages and dishes. Canada as compared with 50 years ago. Ontario dairy products is a tradition based on the values that have shaped dairy LOCAL MILK LOCAL farming for generations. While the know-how and craft have been preserved, the PARTLY-SKIMMED & SKIMMED MILK • It takes the same amount of land resources quality and potential of the ingredient has grown and evolved, making Ontario one Partly-skimmed (1-2% milk fat) milk perfectly versatile, used in (about 1.7 square metres) to produce either a litre of the most unique dairy regions in the country and around the world. baking, cooking or enjoyed on its own. Skimmed milk (0.1% milk fat) of milk or a loaf of bread. is nearly fat-free and extremely refreshing. • A single serving of milk contains more absorbable BUTTERMILK calcium than any other natural food. LOCAL BY NATURE. Perfected. Pasteurization eliminates bacteria and The inimitable tanginess of buttermilk is the result of a specialized Milk is a hyper local food, travelling from the farm to grocery homogenization ensures a smooth and consistent milk bacterial culture added to regular milk. -

Pluralist Universalism

Pluralist Universalism Pluralist Universalism An Asian Americanist Critique of U.S. and Chinese Multiculturalisms WEN JIN The Ohio State University Press | Columbus Copyright © 2012 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jin, Wen, 1977– Pluralist universalism : an Asian Americanist critique of U.S. and Chinese multiculturalisms / Wen Jin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1187-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-0-8142-9288-4 (cd) 1. Multiculturalism in literature. 2. Cultural pluralism in literature. 3. Ethnic relations in literature. 4. Cultural pluralism—China. 5. Cultural pluralism—United States. 6. Multicul- turalism—China. 7. Multiculturalism—United States. 8. China—Ethnic relations. 9. United States—Ethnic relations. 10. Kuo, Alexander—Criticism and interpretation. 11. Zhang, Chengzhi, 1948—Criticism and interpretation. 12. Alameddine, Rabih—Criticism and inter- pretation. 13. Yan, Geling—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. PN56.M8J56 2012 810.9'8951073—dc23 2011044160 Cover design by Mia Risberg Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Mate- rials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Jin Yiyu Zhou Huizhu With love and gratitude CONTENTS Preface ix Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Bridging the Chasm: A Survey -

Yogurt Consumption & Improved Lactose Digestion

Yogurt Consumption & Improved Lactose Digestion Yogurt, kefir and other fermented foods contain health promoting bacteria that influence the gut microbe and contribute to overall health.1 A systematic review published in Nutrition Reviews2 evaluated the impact of fermented dairy food consumption, specifically yogurt, kefir and other fermented milks, on gastrointestinal and cardiovascular health, cancer risk, weight management, diabetes and metabolic health, and bone density.* Among the positive findings, a direct and causal relationship was found between yogurt consumption and lactose digestion and tolerance. This review affirms the beneficial role of yogurt consumption on improved lactose digestion and tolerance. * The review included 47 clinical trials, 6 case control trials, 16 cross-sectional studies and 39 prospective studies (108 studies in total) published between 1979 and 2017. Fermented milk consumption was also consistently associated with: • Reduced risk of breast & colorectal cancer • Reduced risk of type 2 diabetes • Improved weight maintenance • Improved cardiovascular health • Improved bone health • Improved gastrointestinal health2 Did you know? • Yogurt provides 7 essential nutrients including: protein, calcium, phosphorus, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, riboflavin & zinc.3 • The live and active cultures found in yogurt helps to break down lactose, which may make it easier for people with lactose intolerance to digest yogurt.3 • Fermented foods like yogurt are a good sources of nutrients that are important for normal immune function and may help reduce chronic inflammation.3 National Dairy Council’s (NDC) mission it to bring to life the dairy community’s shared vision of a healthy, happy, sustainable world with science as our foundation. On behalf of America’s dairy farmers and importers, NDC strives to help people thrive across the lifespan through science-based information on dairy’s contributions to nutrition, health and sustainable food systems. -

Comparativ Heft 4-2018 Neu Ohne Rezensionen.Indd

The Mongol Peace and Global Medieval Eurasia1 Marie Favereau ABSTRACTS Der Mongolische Frieden (pax mongolica) bezieht sich auf die Zeit, in der die Nachfahren von Dschingis Khan den Großteil der eurasischen Landmasse beherrschten. Er war ein bedeuten- der Moment des globalen Mittelalters, denn er verwandelte die humane Landschaft Eurasiens und verband das Mittelmeer mit Indien und China. Die Mongolen stimulierten neue Formen des Fernhandels, indem sie Vereinbarungen mit den Mamluken, Byzantinern, Italienern und anderen abschlossen. Unter ihrer Herrschaft entstand eine neue Wirtschaftsordnung, die nicht als bloße Wiederbelebung der „Seidenstraßen“ der alten Welt angesehen werden kann. Die Forschung hat den Mongolischen Frieden als kontinentales Phänomen eingeordnet, aber nur wenige Historiker haben neuerdings versucht, dieses Phänomen über die Feststellung eines gegenseitigen Interesses der Mongolen und der Kaufleute hinaus zu analysieren. Dieser Arti- kel vertieft das Verständnis dieser Interdependenz, indem die praktischen Aspekte des ortaq- Systems genauer untersucht werden. Er soll, allgemeiner gesehen, das Konzept des Mongoli- schen Friedens durch einen neuen Ansatz wiederbeleben, der das Handeln der Nomaden in der kommerziellen Wirtschaft in den Blick nimmt. Dies schließt eine Neubewertung der „spiri- tuellen“ Motivationen der Mongolen und ihrer politischen und diplomatischen Fähigkeiten bei der Integration des nördlichen Eurasien in das größte ökonomische Netzwerk der Landmasse ein. 1 This study has benefited from the expertise and contributions of several readers. I thank especially Chris Hann for his support and very helpful comments, and the other members of the panel “Empires, exchange and civili- zational connectivity in Eurasia” (Fifth European Congress on World and Global History), as well as Ilya Afanasyev and Simon Yarrow for all their suggestions. -

Archaeology of Asia

BLACKWELL STUDIES IN GLOBAL ARCHAEOLOGY archaeology of asia Edited by Miriam T. Stark Archaeology of Asia BLACKWELL STUDIES IN GLOBAL ARCHAEOLOGY Series Editors: Lynn Meskell and Rosemary A. Joyce Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology is a series of contemporary texts, each care- fully designed to meet the needs of archaeology instructors and students seeking volumes that treat key regional and thematic areas of archaeological study. Each volume in the series, compiled by its own editor, includes 12–15 newly commis- sioned articles by top scholars within the volume’s thematic, regional, or temporal area of focus. What sets the Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology apart from other available texts is that their approach is accessible, yet does not sacrifice theoretical sophistication. The series editors are committed to the idea that usable teaching texts need not lack ambition. To the contrary, the Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology aim to immerse readers in fundamental archaeological ideas and concepts, but also to illu- minate more advanced concepts, thereby exposing readers to some of the most exciting contemporary developments in the field. Inasmuch, these volumes are designed not only as classic texts, but as guides to the vital and exciting nature of archaeology as a discipline. 1. Mesoamerican Archaeology: Theory and Practice Edited by Julia A. Hendon and Rosemary A. Joyce 2. Andean Archaeology Edited by Helaine Silverman 3. African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction Edited by Ann Brower Stahl 4. Archaeologies of the Middle East: Critical Perspectives Edited by Susan Pollock and Reinhard Bernbeck 5. North American Archaeology Edited by Timothy R. Pauketat and Diana DiPaolo Loren 6.