Orangutan Reintroduction and Protection Final Report 2001.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Cover Letter

PARC Prisoner Resource Directory - Last Updated April 2014 1 Core Volunteers B♀ (rita d. brown) Greetings, April 2014 Pat Foley Scott Nelson Welcome to the latest edition of the PARC Prisoner Resource Directory, which has been fully updated as of April 2014. We wish to thank those readers who have written back this past year with letters Sissy Pradier and stories and who have returned our evaluation form, as this allows us to get a better idea of the true Penny Schoner readership of the directory and let us know which direction to take when adding new categories or information. Special thanks again to those who pass on the directory – according to your reports, our Taeva Shefler resource directory is widely circulated and viewed by an average of 15 or more people. Mindy Stone Starting with this edition we have reorganized many resources that were formerly listed in individual categories into a state-by-state listing. Thus for instance, the former entries for Innocence Projects, Prison-Based College Programs, and Family & Visiting Resources are now listed in the Community corresponding state in which the organization is based or primarily offers its services. Our other categories Advisory Board with listings affecting prisoners on a nationwide basis will continue with their own sections, such as Women’s Organizations, Death Penalty Resources, and Religious Programs / Spiritual Resources. B♀ (rita d. brown) Rose Braz PARC also has been closely following the ongoing federal lawsuit over cruel and unusual conditions in California’s security housing units (Ashker v Brown, 4:09-cv-05796-CW), which was filed jointly Angela Davis by the nationally-recognized Center for Constitutional Rights, Oakland-based California Prison Focus, and San Francisco-based Legal Services for Prisoners with Children. -

Trial Iivaits Election

trial iivaits election Both sides get time to study thousands of secret papers... page 10 >• i« 4k. .4 <1% ■ *pVt- .4f|> 14- Dr. Crane’s Quiz UConn prof Wetlands error costs town $200,000 By Andrew Yurkovsky says Sound Manchester Herald be raised. ' 1. The phrase “ 2 x 4” involves the worker who Weiss would not say-what damages most likely also employs a It’s going to cost Manchester were originally sought by Brunoli k BLOW TORCH HOD MITER BOX BEEN Sons, the contractor. Town officials is improving $200,000— not counting legal expenses r iH H L HAMMER — to settle its dispute with the U.S. had said previously, however, that the 2. Which "back” usually involves a bundle of Arm y Corps of Engineers over the stoppage would cost from $12,000 to GROTON (AP) - The Long greenbacks? construction on wetlands of an addi $15,000 per day. Calculated on the Island Sound has been troubled n !. ^ CANVASBACK RAZORBACK KICKBACK tion to the town’s sewage treatment basis'of 28 lost work days, those SWflirBACK this summer by heavy rains, hot plant. damages i^ould Have ranged between 3. Which one of these is least likely to lower a temperatures and industrial The town Board of Directors, $338,000 and $420,000. woman’s bustline? waste but a University of Connec ending a lengthy and freQuently angry Work stopped June 23, but the town JOGGING TENNIS SWIMMING ICE SKATING ticut professor predicted Friday dispute with federal officials, unanim ‘ had been alloWed by the U.S. attorney 4.Which one of these is most likely to lower a the summer could end without a ously approved an agreement Friday to resume work for a four-day period woman’s bustline? major fish kill if nothing serious that w ill allow the town to expand the at the end of June. -

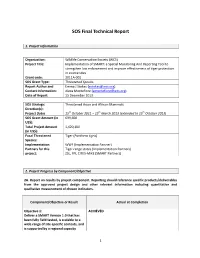

SOS Final Technical Report

SOS Final Technical Report 1. Project Information Organization: Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Project Title: Implementation of SMART: a Spatial Monitoring And Reporting Tool to strengthen law enforcement and improve effectiveness of tiger protection in source sites Grant code: 2011A-001 SOS Grant Type: Threatened Species Report Author and Emma J Stokes ([email protected]) Contact Information: Alexa Montefiore ([email protected]) Date of Report: 15 December 2013 SOS Strategic Threatened Asian and African Mammals Direction(s): Project Dates 15th October 2011 – 15th March 2013 (extended to 15th October 2013) SOS Grant Amount (in 699,600 US$): Total Project Amount 1,420,100 (in US$): Focal Threatened Tiger (Panthera tigris) Species: Implementation WWF (Implementation Partner) Partners for this Tiger range states (Implementation Partners) project: ZSL, FFI, CITES-MIKE (SMART Partners) 2. Project Progress by Component/Objective 2A. Report on results by project component. Reporting should reference specific products/deliverables from the approved project design and other relevant information including quantitative and qualitative measurement of chosen indicators. Component/Objective or Result Actual at Completion Objective 1: ACHIEVED Deliver a SMART Version 1.0 that has been fully field-tested, is scalable to a wide range of site-specific contexts, and is supported by a regional capacity 1 building strategy. Result 1.1: - SMART 1.0 publicly released Feb 2013. A SMART system that is scalable, fully - Two subsequent updates released based on early field-tested and supported by a regional field testing (current version 1.1.2) capacity building strategy is in place in 9 - Software translated into Thai, Vietnamese and implementation sites. -

Bako National Park S60 Gunung Mulu NP

TOTAL COMBINE AREA (ha) NO NAME OF TPA (As of Nov 2020) GAZETTE No. GAZETTEMENT DATE LAND MARINE Total 1 Bako National Park S60 1 May, 1957 2,727.00 0.00 2,727.00 Gunung Mulu NP (All) Gunong Mulu National Park 2853 1 August, 1974 2 85,671.00 0.00 85,671.00 Gunong Mulu National Park (Ext.I) 2621 9 February, 2012 Gunong Mulu National Park (Ext. II) 3161 4 May, 2011 3 Niah National Park 50 23 November, 1974 3,139.00 0.00 3,139.00 4 Lambir Hills National Park 1899 15 May, 1975 6,949.00 0.00 6,949.00 Similajau NP (All) Similajau National Park 1337 25 November, 1976 8,996.00 5 22,120.00 Similajau National Park (1st Ext.) 2248 5 April, 2000 Similajau National Park (Ext.II) 130 23 May, 2000 13,124.00 6 Gunung Gading National Park 3289 1 August, 1983 4,196.00 0.00 4,196.00 7 Kubah National Park 2220 17 November, 1988 2,230.00 0.00 2,230.00 8 Batang Ai National Park 1288 28 February, 1991 24,040.00 0.00 24,040.00 9 Loagan Bunut National Park 2790 25 June, 1990 10,736.00 0.00 10,736.00 10 Tanjung Datu National Park 1102 16 March, 1994 752.00 627.00 1,379.00 11 Talang Satang National Park 3565 27 September, 1999 0.00 19,414.00 19,414.00 Maludam NP 12 Maludam National Park 1997 30 March, 2000 53,568.00 0.00 53,568.00 Maludam National Park (Ext 1) 2337 13 March, 2013 13 Bukit Tiban National Park 1998 17 February, 2000 8,000.00 0.00 8,000.00 14 Rajang Mangroves National Park 2833 29 May, 2000 9,373.00 0.00 9,373.00 Gunung Buda National Park (All) Gunung Buda National Park 189 14 September, 2000 15 11,307.00 0.00 11,307.00 Gunung Buda National Park (1st Ext) 3163 17 March, 2011 16 Kuching Wetland National Park 3512 24 July, 2002 6,610.00 0.00 6,610.00 Pulong Tau NP (All) 17 Pulong Tau National Park 919 10 January, 2005 69,817.00 0.00 69,817.00 Pulong Tau National Park(ext I) 2472 6 January, 2013 18 Usun Apau National Park 3153 5 May, 2005 49,355.00 0.00 49,355.00 19 Miri-Sibuti Coral Reefs National Park 1144 16 March, 2007 0.00 186,930.00 186,930.00 Santubong National Park (All) 20 Santubong National Park 2303 28 May, 2007 1,641.00 2,165.00 3,806.00 Santubong NP (Ext. -

Texas Public Safety Threat Overview 2017 (PDF)

UNCLASSIFIED LAW ENFORCEMENT SEN Texas Public Safety Threat Overview A State Intelligence Estimate Produced by the Texas Department of Public Safety In collaboration with other law enforcement and homeland security agencies January 2017 1 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Executive Summary (U) Texas faces the full spectrum of threats, and the state’s vast size, geography, and large population present unique challenges to public safety and homeland security. Texas employs a systematic approach to detect, assess, and prioritize public safety threats within seven categories: terrorism, crime, motor vehicle crashes, natural disasters, public health threats, industrial accidents, and cyber threats. (U) Due to the recent actions of lone offenders or small groups affiliated with or inspired by the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and other foreign terrorist organizations, we assess that the current terrorism threat to Texas is elevated. We recognize that ISIS has had considerable success in inspiring and inciting lone offenders to attack targets in the United States and other Western countries using simple yet effective tactics that are difficult to detect and disrupt. We expect this heightened threat to persist over at least the next year, due in part to the relatively high number of recent terrorism-related arrests and thwarted plots inside the US, and the prevalence and effectiveness of ISIS’s online recruitment and incitement messaging, as the organization is slowly defeated on the battlefield. We are especially concerned about the potential for terrorist infiltration across the US-Mexico border, particularly as foreign terrorist fighters depart Syria and Iraq and enter global migration flows. We are concerned about the challenges associated with the security vetting of Syrian war refugees or asylum seekers who are resettled in Texas – namely, that derogatory security information about individuals is inaccessible or nonexistent. -

A 040909 Breeze Thursday

Post Comments, share Views, read Blogs on CaPe-Coral-daily-Breeze.Com Day three Little League CAPE CORAL county tourney continues DAILY BREEZE — SPORTS WEATHER: Partly Cloudy • Tonight: Mostly Clear • Wednesday: Sunny — 2A cape-coral-daily-breeze.com Vol. 48, No. 92 Tuesday, April 21, 2009 50 cents Man to serve life for home invasion shooting death Andrew Marcus told Lee Circuit Judge Mark Steinbeck Attorneys plan to appeal conviction during Morales’ sentencing hearing Monday, citing the use By CONNOR HOLMES der, two counts of attempted cutors. Two others were shot, of firearms to kill Gomez and [email protected] second-degree murder with a and another man was beaten injure two others. One of five defendants in the firearm and aggravated battery with a tire iron. Steinbeck sentenced Anibal 2005 home invasion shooting with a deadly weapon by a Lee Fort Myers police testified Morales to serve three manda- Morales death of Jose Gomez was sen- County jury in early February. they later found the murder tory life sentences and 15 years tenced to life in prison Monday Morales fatally shot Gomez weapon in Morales’ car during in prison consecutively for the afternoon in a Lee County through the heart during a rob- a traffic stop. charges of which he has been courtroom. bery at 18060 Nalle Road, “We believe this case calls convicted. Anibal Morales, 22, was North Fort Myers, in November for the maximum sentence ... ” convicted of first-degree mur- 2005, according to state prose- Assistant State Attorney See SENTENCE, page 6A Expert speaker City manager calls take-home vehicle audit report wrong Refuses to go into detail By GRAY ROHRER [email protected] “The finding that the city Cape Coral City Manager is paying insurance on Terry Stewart denied one of the more cars than it owns is more glaring contentions of the inaccurate.” city’s take-home vehicle audit report Monday, saying the city — City Manager is not paying insurance on Terry Stewart more vehicles than it owns. -

El Rodeo Staff Writer Munications with an Emphasis on Radio, TV, and Film from the California State at Only 42-Years-Old, Mr

Friday, September 30, 2016 www.elrodeonews.com El ElRodeo Rancho High School Volume 65, Issue 1 Music-loving Mr. Lyons looks to strike a chord at The Ranch BY NAYELI HERNANDEZ has a Bachelor’s Degree in Mass Com- EL RODEO STAFF WRITER munications with an emphasis on Radio, TV, and Film from the California State At only 42-years-old, Mr. Jonathan University, San Bernadino. His school- Lyons has done everything from dabbling ing quickly leads him to a career in the in the music business to teaching United music industry before he received his States History. His next stop in life is at teaching credential from California State our very own, El Rancho High School. University, Northridge and his Adminis- Mr. Lyons comes to us from Ga- tration Master’s Degree at the California brielino High School in San Gabriel, State Polytechnic University, Pomona. where he was an Assistant Principal for “At one point I worked for Ma- the last six years. The move to El Ran- donna’s record label (Maverick Studios),” cho wasn’t at all planned or expected. said Lyons, “I was in promotions so I can “Most people, if they’re looking actually lay claim to the fact that I have to move forward, they don’t spend that been in the same room as Madonna.” much time in one area,” said Mr. Ly- Growing up in San Bernadino and ons, “To be totally honest, this was a late working in the heart of the music indus- process. I had already started school, try, Lyons has quite a diverse taste. -

Trial by Fire F Orest F Ires and F Orestry P Olicy in I Ndonesia’ S E Ra of C Risis and R Eform

TRIAL BY FIRE F OREST F IRES AND F ORESTRY P OLICY IN I NDONESIA’ S E RA OF C RISIS AND R EFORM CHARLES VICTOR BARBER JAMES SCHWEITHELM WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE FOREST FRONTIERS INITIATIVE IN COLLABORATION WITH WWF-INDONESIA & TELAPAK INDONESIA FOUNDATION INDONESIA’S FOREST COVER Notes: (a) Hotspots, showing ground thermal activity detected with the NOAA AVHRR sensor, represent an area of approximately 1 square kilometer. Data from August - December 1997 were processed by IFFM-GTZ, FFPCP (b) Forest cover is from The Last Frontier Forests, Bryant, Nielsen, and Tangley, 1997. "Frontier forest" refers to large, ecologically intact and relatively undisturbed natural forests. "Non-frontier forests" are dominated by eventually degrade the ecosystem. See Bryant, Nielsen, and Tangley for detailed definitions. AND 1997-98 FIRE HOT SPOTS CA, and FFPMP-EU. ondary forests, plantations, degraded forest, and patches of primary forest not large enough to qualify as frontier forest. "Threatened frontier forests" are forests where ongoing or planned human activities will TRIAL BY FIRE F OREST F IRES AND F ORESTRY P OLICY IN I NDONESIA’ S E RA OF C RISIS AND R EFORM CHARLES VICTOR BARBER JAMES SCHWEITHELM WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE FOREST FRONTIERS INITIATIVE IN COLLABORATION WITH WWF-INDONESIA & TELAPAK INDONESIA FOUNDATION TO COME Publications Director Hyacinth Billings Production Manager Designed by: Papyrus Design Group, Washington, DC Each World Resources Institute report represents a timely, scholarly treatment of a subject of public concern. WRI takes responsibility for choosing the study topics and guaranteeing its authors and researchers freedom of inquiry. It also solicits and responds to the guidance of advisory panels and expert reviewers. -

Comparative Distribution and Diversity of Bats from Selected Localities in Sarawak

Borneo J. Resour. Sci. Tech. (2011) 1: 1-13 COMPARATIVE DISTRIBUTION AND DIVERSITY OF BATS FROM SELECTED LOCALITIES IN SARAWAK JAYARAJ VIJAYA KUMARAN*1, BESAR KETOL2, WAHAP MARNI2, ISA SAIT2, MOHAMAD JALANI MORTADA2, FAISAL ALI ANWARALI KHAN2, 3, FONG POOI HAR2, 4, LESLIE S. HALL5 & MOHD TAJUDDIN ABDULLAH2 1Faculty of Agro Industry and Natural Resources, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Locked bag 36, Pengkalan Chepa, 16100 Kota Bharu, Kelantan; 2Department of Zoology, Faculty of Resource Science and Technology, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, Malaysia; 3Department of Biological Sciences, Texas Tech University, Main and Flint, Lubbock, Texas 79409, USA; 4Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Applied Sciences, UCSI University, No.1, Jalan Menara Gading, UCSI Heights, 56000 Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 5Visiting Research Fellow, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Resource Science and Technology, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak ABSTRACT Surveys on the chiropteran diversity were conducted at eight different localities in Sarawak to document the bat diversity as well as to estimate the composition of bats in these areas. The major finding of bat surveys shows that montane areas have distinct chiropteran composition compared with those in lowland and logged areas. Disturbed habitats do pose a threat to the overall diversity of bats, with the generalist bats been more successful in colonising altered area than those with specialised habitat requirements. Sampling of bats targeted at different site and vegetation type from several protected areas in Sarawak have revealed the current record of bats in Sarawak and its diversity can be monitored for better management of biodiversity in this important region. Keywords: Diversity, chiroptera, forest types, montane, habitat disturbance, Borneo INTRODUCTION 1940, later revised by Ellerman & Morisson-Scott 1955). -

Appendices and Heferences

Section V Appendices and Heferences A sub-adult female Sumatran orang-utan cif the dark, Southern type. 417 Section V: appendices and references A sub-adult male Sumatran orang-utan, apparently of mixed descent. 418 APPENDIX 1 TABLEXXVII List of vernacular names of the orang-utan (after Yasuma, 1994 and pers. dos.). Vernacular name Ethnic or cultural identity; [region) Hirang (utan) Kayan He/ong lietiea Kayan and Kenyah; [Modang, Long Bleh] Kaheyu Ngadju; Southern groups, [east Central Kalimantan] Kahui Murut; [Northern west Kai. groups, south Sarawak] Keö, Ke'u, Keyu, or Ma'anyan and Bawo; Southern groups, [Kanowit, South-Kal. prov. Kuyuh. and east of S. Barito] Kihiyu Ot Danum; [north Centr. Kai. prov.] Kisau or Kog'iu Orang Sungai; Northern groups, [east-Sabah] Kogiu Kadazan; Northern groups, [north Sabah] Koju Punan: Northern groups, [S. Blayan] Kuyang, Kuye . Kenyah, Kayan and Punan: [Apo Kayan, Badung, Bakung, Lepok Jalan, Lepok Yau, S. Tubuh, S. Lurah, Melap, lower S. Kayan] Maias Bidayuh, lban and Lun Dayeh; [Sarawak north of G. Niut, north West or Mayas Kai. prov., north Sarawak and north East Kai prov.; also western Malayu; West-Kalimantan prov.] Dyang Dok Kenyah; [Badeng, 5. Lurah] Drang Hutan modern lndonesians, islamized dayaks; transmigrants [lndo-Malay or Drang-utan archipelago] and Dusun [North Sabah] Tjaului townspeople [Balikpapan, Samarinda] Ulan!Urang Utan islamized Dayaks and coastal Kenyah; [Tidung regency, northeast- Kalimantan] Uraagng Utatn Benuaq, Bahau and Tunjung; [S. Kedangpahu, along S. Mahakam] also transmigrants [western East-Kalimantan] Uyang Paya .. Kenyah; Apo Kayan, [north East Kai. prov.] Mawas Batak, Malays; [Sumatra] and the Batek [in W. -

Transboundary Conservation and Peace-Building: Lessons from Forest Projects

Transboundary Conservation and Peace-building: Lessons from forest projects International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) and United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies (UNU-IAS) This is the first version of the report. A final version is planned to be published in December 2010. The United Nations University Institute of Advanced Studies (UNU-IAS) is a global think tank whose mission is “to advance knowledge and promote learning for policy-making to meet the challenges of sustainable development”. UNU-IAS undertakes research and postgraduate education to identify and address strategic issues of concern for all humankind, for governments, decision-makers, and particularly, for developing countries. Established in 1996, the Institute convenes expertise from disciplines such as economics, law, social and natural sciences to better understand and contribute creative solutions to pressing global concerns, with research and programmatic activities related to current debates on sustainable development: . Biodiplomacy Initiative . Ecosystem Services Assessment . Satoyama Initiative . Sustainable Development Governance . Education for Sustainable Development . Marine Governance . Traditional Knowledge Initiative . Science and Technology for Sustainable Societies . Sustainable Urban Futures UNU-IAS, based in Yokohama, Japan, has two International Operating Units: the Operating Unit Ishikawa/ Kanazawa (OUIK) in Japan, and the Traditional Knowledge Initiative (TKI) in Australia. Transboundary Conservation and Peace-building: Lessons