Glacier National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peaks-Glacier

Glacier National Park Summit List ©2003, 2006 Glacier Mountaineering Society Page 1 Summit El Quadrangle Notes ❑ Adair Ridge 5,366 Camas Ridge West ❑ Ahern Peak 8,749 Ahern Pass ❑ Allen Mountain 9,376 Many Glacier ❑ Almost-A-Dog Mtn. 8,922 Mount Stimson ❑ Altyn Peak 7,947 Many Glacier ❑ Amphitheater Mountain 8,690 Cut Bank Pass ❑ Anaconda Peak 8,279 Mount Geduhn ❑ Angel Wing 7,430 Many Glacier ❑ Apgar Mountains 6,651 McGee Meadow ❑ Apikuni Mountain 9,068 Many Glacier ❑ Appistoki Peak 8,164 Squaw Mountain ❑ B-7 Pillar (3) 8,712 Ahern Pass ❑ Bad Marriage Mtn. 8,350 Cut Bank Pass ❑ Baring Point 7,306 Rising Sun ❑ Barrier Buttes 7,402 Mount Rockwell ❑ Basin Mountain 6,920 Kiowa ❑ Battlement Mountain 8,830 Mount Saint Nicholas ❑ Bear Mountain 8,841 Mount Cleveland ❑ Bear Mountain Point 6,300 Gable Mountain ❑ Bearhat Mountain 8,684 Mount Cannon ❑ Bearhead Mountain 8,406 Squaw Mountain ❑ Belton Hills 6,339 Lake McDonald West ❑ Bighorn Peak 7,185 Vulture Peak ❑ Bishops Cap 9,127 Logan Pass ❑ Bison Mountain 7,833 Squaw Mountain ❑ Blackfoot Mountain 9,574 Mount Jackson ❑ Blacktail Hills 6,092 Blacktail ❑ Boulder Peak 8,528 Mount Carter ❑ Boulder Ridge 6,415 Lake Sherburne ❑ Brave Dog Mountain 8,446 Blacktail ❑ Brown, Mount 8,565 Mount Cannon ❑ Bullhead Point 7,445 Many Glacier ❑ Calf Robe Mountain 7,920 Squaw Mountain ❑ Campbell Mountain 8,245 Porcupine Ridge ❑ Cannon, Mount 8,952 Mount Cannon ❑ Cannon, Mount, SW Pk. 8,716 Mount Cannon ❑ Caper Peak 8,310 Mount Rockwell ❑ Carter, Mount 9,843 Mount Carter ❑ Cataract Mountain 8,180 Logan Pass ❑ Cathedral -

Montana Official 2018-2019 Visitor Guide

KALISPELL MONTANA OFFICIAL 2018-2019 VISITOR GUIDE #DISCOVERKALISPELL 888-888-2308 DISCOVERKALISPELL.COM DISCOVER KALISPELL TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 DISCOVER KALISPELL 6 GETTING HERE 7 GLACIER NATIONAL PARK 10 DAY HIKES 11 SCENIC DRIVES 12 WILD & SCENIC 14 QUICK PICKS 23 FAMILY TIME 24 FLATHEAD LAKE 25 EVENTS 26 LODGING 28 EAT & DRINK 32 LOCAL FLAVOR 35 CULTURE 37 SHOPPING 39 PLAN A MEETING 41 COMMUNITY 44 RESOURCES CONNECTING WITH KALISPELL To help with your trip planning or to answer questions during your visit: Kalispell Visitor Information Center Photo: Tom Robertson, Foys To Blacktail Trails Robertson, Foys To Photo: Tom 15 Depot Park, Kalispell, MT 59901 406-758-2811or 888-888-2308 DiscoverKalispellMontana @visit_Kalispell DiscoverKalispellMontana Discover Kalispell View mobile friendly guide or request a mailed copy at: WWW.DISCOVERKALISPELL.COM Cover Photo: Tyrel Johnson, Glacier Park Boat Company’s Morning Eagle on Lake Josephine www.discoverkalispell.com | 888-888-2308 3 DISCOVER KALISPELL WELCOME TO KALISPELL Photos: Tom Robertson, Kalispell Chamber, Mike Chilcoat Robertson, Kalispell Chamber, Photos: Tom here the spirit of Northwest Montana lives. Where the mighty mountains of the Crown of the Continent soar. Where the cold, clear Flathead River snakes from wild lands in Glacier National Park and the Bob WMarshall Wilderness to the largest freshwater lake in the west. Where you can plan ahead for a trip of wonder—or let each new moment lead your adventures. Follow the open road to see what’s at the very end. Lay out the map and chart a course to its furthest corner. Or explore the galleries, museums, and shops in historic downtown Kalispell—and maybe let the bakery tempt you into an unexpected sweet treat. -

Going-To-The-Sun Road Historic District, Glacier National Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2002 Going-to-the-Sun Road Historic District Glacier National Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Going-to-the-Sun Road Historic District Glacier National Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national -

Glacier NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA

Glacier NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA, UNITED STATES SECTION WATERTON-GLACIER INTERNATIONAL PEACE PARK Divide in northwestern Montana, contains nearly 1,600 ivy. We suggest that you pack your lunch, leave your without being burdened with camping equipment, you may square miles of some of the most spectacular scenery and automobile in a parking area, and spend a day or as much hike to either Sperry Chalets or Granite Park Chalets, primitive wilderness in the entire Rocky Mountain region. time as you can spare in the out of doors. Intimacy with where meals and overnight accommodations are available. Glacier From the park, streams flow northward to Hudson Bay, nature is one of the priceless experiences offered in this There are shelter cabins at Gunsight Lake and Gunsight eastward to the Gulf of Mexico, and westward to the Pa mountain sanctuary. Surely a hike into the wilderness will Pass, Fifty Mountain, and Stoney Indian Pass. The shelter cific. It is a land of sharp, precipitous peaks and sheer be the highlight of your visit to the park and will provide cabins are equipped with beds and cooking stoves, but you NATIONAL PARK knife-edged ridges, girdled with forests. Alpine glaciers you with many vivid memories. will have to bring your own sleeping and cooking gear. lie in the shadow of towering walls at the head of great ice- Trail trips range in length from short, 15-minute walks For back-country travel, you will need a topographic map carved valleys. along self-guiding nature trails to hikes that may extend that shows trails, streams, lakes, mountains, and glaciers. -

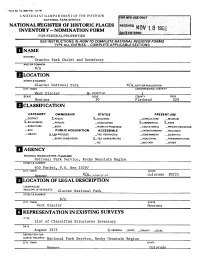

Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION

Form No. i0-306 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR lli|$|l;!tli:®pls NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES iliiiii: INVENTORY- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glacier National Park NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT West Glacier X- VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Montana 30 Flathead 029 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X.PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL X_RARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N/AN PR OCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY _OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (Happlicable) ______National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region STREET & NUMBER ____655 Parfet, P.O. Box 25287 CITY. TOWN STATE N/A _____Denver VICINITY OF Colorado 80225 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Qlacier National STREET & NUMBER N/A CITY. TOWN STATE West Glacier Montana REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE August 1975 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region CITY. TOWN STATE Colorado^ DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory are situated near the Swiftcurrent Pass in Glacier National Park at an elevation of 7,000 feet. -

NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM B

NFS Fbnn 10-900 'Oitntf* 024-0019 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service I * II b 1995 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM iNTERAGENCY RBOr- „ NATIONAL i3AR: 1. Name of Property fe NAllUNAL HhblbiLH d»vu,su historic name: Glacier National Park Tourist Trails: Inside Trail; South Circle; North Circle other name/site number Glacier National Park Circle Trails 2. Location street & number N/A not for publication: n/a vicinity: Glacier National Park (GLAC) city/town: N/A state: Montana code: MT county: Flathead; Glacier code: 29; 35 zip code: 59938 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1988, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant _ nationally X statewide _ locally. ( See continuation sheet for additional comments.) ) 9. STgnatuTBof 'certifying official/Title National Park Service State or Federal agency or bureau In my opinion, thejiuipKty. does not meet the National Register criteria. gj-^ 1B> 2 9 1995. Signature of commenting or other o Date Montana State Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service -

Agassiz Glacier Glacier National Park, MT

Agassiz Glacier Glacier National Park, MT W. C. Alden photo Greg Pederson photo 1913 courtesy of GNP archives 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Agassiz Glacier Glacier National Park, MT M. V. Walker photo Greg Pederson photo 1943 courtesy of GNP archives 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Blackfoot – Jackson Glacier Glacier National Park, MT E. C. Stebinger photo courtesy of GNP 1914 archives Lisa McKeon photo 2009 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Blackfoot and Jackson Glaciers Glacier National Park, MT 1911 EC Stebinger photo GNP Archives 2009 Lisa McKeon photo USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Boulder Glacier Glacier National Park, MT T. J. Hileman photo Jerry DeSanto photo 1932 courtesy of GNP archives 1988 K. Ross Toole Archives Mansfield Library, UM USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Boulder Glacier Glacier National Park, MT T. J. Hileman photo Greg Pederson photo 1932 courtesy of GNP archives 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Boulder Glacier Glacier National Park, MT Morton Elrod photo circa 1910 courtesy of GNP archives Fagre / Pederson photo 2007 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Chaney Glacier Glacier National Park, MT M.R. Campbell photo Blase Reardon photo 1911 USGS Photographic Library 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Chaney Glacier Glacier National Park, MT M.R. Campbell photo Blase Reardon photo 1911 USGS Photographic Library 2005 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Grant Glacier Glacier National Park, MT Morton Elrod photo Karen Holzer photo 1902 courtesy of GNP Archives 1998 USGS USGS Repeat Photography Project http://nrmsc.usgs.gov/repeatphoto/ Grinnell Glacier Glacier National Park, MT F. -

Geochemical Evidence of Anthropogenic Impacts on Swiftcurrent Lake, Glacier National Park, Mt

KECK GEOLOGY CONSORTIUM PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL KECK RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM IN GEOLOGY April 2011 Union College, Schenectady, NY Dr. Robert J. Varga, Editor Director, Keck Geology Consortium Pomona College Dr. Holli Frey Symposium Convenor Union College Carol Morgan Keck Geology Consortium Administrative Assistant Diane Kadyk Symposium Proceedings Layout & Design Department of Earth & Environment Franklin & Marshall College Keck Geology Consortium Geology Department, Pomona College 185 E. 6th St., Claremont, CA 91711 (909) 607-0651, [email protected], keckgeology.org ISSN# 1528-7491 The Consortium Colleges The National Science Foundation ExxonMobil Corporation KECK GEOLOGY CONSORTIUM PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWENTY-FOURTH ANNUAL KECK RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM IN GEOLOGY ISSN# 1528-7491 April 2011 Robert J. Varga Keck Geology Consortium Diane Kadyk Editor and Keck Director Pomona College Proceedings Layout & Design Pomona College 185 E 6th St., Claremont, CA Franklin & Marshall College 91711 Keck Geology Consortium Member Institutions: Amherst College, Beloit College, Carleton College, Colgate University, The College of Wooster, The Colorado College, Franklin & Marshall College, Macalester College, Mt Holyoke College, Oberlin College, Pomona College, Smith College, Trinity University, Union College, Washington & Lee University, Wesleyan University, Whitman College, Williams College 2010-2011 PROJECTS FORMATION OF BASEMENT-INVOLVED FORELAND ARCHES: INTEGRATED STRUCTURAL AND SEISMOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN THE BIGHORN MOUNTAINS, WYOMING Faculty: CHRISTINE SIDDOWAY, MEGAN ANDERSON, Colorado College, ERIC ERSLEV, University of Wyoming Students: MOLLY CHAMBERLIN, Texas A&M University, ELIZABETH DALLEY, Oberlin College, JOHN SPENCE HORNBUCKLE III, Washington and Lee University, BRYAN MCATEE, Lafayette College, DAVID OAKLEY, Williams College, DREW C. THAYER, Colorado College, CHAD TREXLER, Whitman College, TRIANA N. UFRET, University of Puerto Rico, BRENNAN YOUNG, Utah State University. -

Many Glacier Hotel Unveils 13 Years of Renovations

Many Glacier Hotel unveils 13 years of renovations https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=29&v=__-MuO5M-co GLACIER NATIONAL PARK - The Many Glacier Hotel, The biggest and possibly the most time-consuming one of the most historic structures in Glacier National project was the recreation of the helical stair case that Park was nearly closed down in 2004 before a group of was taken out in the 1950’s in order to make room for a architects and park enthusiasts began a renovation plan gift shop. that ended up lasting 13 years. Anderson says they had some help from the past The hotel was built by the Great Northern Railroad allowing them to recreate the staircase almost identical Company which was seen as a gateway to Asia for all the to what it was before. business they did overseas there. The Anderson Hallas “It presented some interesting challenges because the Architecture company has worked to renovate the hotel original was not build to Code, we have to design to while still holding onto the history of the 1920’s building. Code today, but the benefit was that we had the original One of those major projects was restoring the lighting in drawings, so we worked with those originals drawings the lobby and the main dining room. to create essentially almost exactly what was here historically,” Anderson said. The new light fixtures are modeled from the original Asian style paper lanterns that were in the original lobby Anderson added they are not fully done with the -- and architect Nan Anderson says they are her favorite renovations but said the most important thing is that part. -

Fire Frequency During the Last Millennium in the Grinnell Glacier and Swiftcurrent Valley Drainage Basins, Glacier National Park, Montana

Fire Frequency During the Last Millennium in the Grinnell Glacier and Swiftcurrent Valley Drainage Basins, Glacier National Park, Montana A Senior Thesis presented to The Faculty of the Department of Geology Bachelor of Arts Madison Evans Andres The Colorado College May 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Chapter 1-Introduction 1 Chapter 2-Previous Work 5 Fire as an Earth System Process 5 Fire Records 6 Fire in the northern Rocky Mountain region 7 Fire in Glacier National Park 9 Chapter 3-Study Area 11 Chapter 4-Methods 15 Field Methods 15 Laboratory Methods 15 Initial Core Descriptions 15 Charcoal Methods 16 Dating Techniques 17 Chapter 5-Results 20 Lithology 20 Chronology 20 Charcoal Results 21 Chapter 6-Discussion and Conclusions 27 References 34 Appendices Appendix 1: Initial Core Description Sheets 37 Appendix 2: Charcoal Count Sheets 40 ii List of Figures Figure 1: Geologic map of the Many Glacier region 3 Figure 2: Primary and secondary charcoal schematic diagram 8 Figure 3: Bathymetric data for Swiftcurrent Lake with core locations 10 Figure 4: Image of 3 drainage basins for Swiftcurrent Lake 13 Figure 5: Swiftcurrent lithologic results 22 Figure 6: Loss-on-ignition organic carbon comparison 24 Figure 7: Age-to-depth model based on LOI comparison 25 Figure 8: CHAR rates for ~1700 year record 25 Figure 9: Fire frequency for ~1700 year record 32 List of Tables Table 1: Monthly climate summary for Glacier National Park, MT 13 Table 2: Average annual visitation rate for Glacier National Park, MT 13 Table 3: Parameter file input for CharAnalysis computer program 19 Table 4: Comparison of factors contributing to CHAR rates 32 iii Acknowledgements It is important to acknowledge the incredible support that I have received throughout this yearlong process. -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Christmas in Glacier: an Anthology Also in This Issue: the 1936 Swiftcurrent Valley Forest Fire, Hiking the Nyack Valley, Gearjamming in the 1950’S, and More!

Voice of the Glacier Park Foundation ■ Fall 2001 ■ Volume XIV, No. 3 (Illustration by John Hagen.) Mount St. Nicholas. Christmas in Glacier: An Anthology Also in this issue: The 1936 Swiftcurrent Valley Forest Fire, Hiking the Nyack Valley, Gearjamming in the 1950’s, and more! The Inside Trail ◆ Fall 2001 ◆ 1 INSIDE NEWS of Glacier National Park Lewis Leaves for Yellowstone Lewis has been well-liked by the would cost less and take less time. Glacier National Park is losing its public and by park staff. She has This plan would involve closing superintendent for the second time presided over a key success for Gla- sections of the Road on alternat- in two years. Suzanne Lewis, who cier in facilitating the renovation of ing sides of Logan Pass, and could came to Glacier in April 2001, is the park’s red buses (see update, p. heavily impact local businesses. transferring to Yellowstone National 24). The committee also rejected slower- paced and more expensive options Park to assume the superintendency Sun Road Committee Reports there. Lewis’ predecessor, David (e.g., 20 years of work at $154 A 16-member Going-to-the-Sun Mihalic, transferred to Yosemite af- million). Road Citizens’ Advisory Commit- ter having been absent from Glacier tee issued recommendations to the The committee’s recommenda- for much of his last two years, pur- Park Service this fall. The com- tions are not binding on the Park suing a course of training for senior mittee had spent a year and a half Service. The Service will make a Park Service executives.