From the Department of Physiology, University of Aberdeen 1. in Cats, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anatomy of Th-E Blood Vascular System of the Fox ,Squirrel

THE ANATOMY OF TH-E BLOOD VASCULAR SYSTEM OF THE FOX ,SQUIRREL. §CIURUS NlGER. .RUFIVENTEB (OEOEEROY) Thai: for the 009m of M. S. MICHIGAN STATE COLLEGE Thomas William Jenkins 1950 THulS' ifliillifllfllilllljllljIi\Ill\ljilllHliLlilHlLHl This is to certifg that the thesis entitled The Anatomy of the Blood Vascular System of the Fox Squirrel. Sciurus niger rufiventer (Geoffroy) presented by Thomas William Jenkins has been accepted towards fulfillment of the requirements for A degree in MEL Major professor Date May 23’ 19500 0-169 q/m Np” THE ANATOMY OF THE BLOOD VASCULAR SYSTEM OF THE FOX SQUIRREL, SCIURUS NIGER RUFIVENTER (GEOFFROY) By THOMAS WILLIAM JENKINS w L-Ooffi A THESIS Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of Michigan State College of Agriculture and Applied Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Zoology 1950 \ THESlSfi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following persons of the Zoology Department: Dr. R. A. Fennell, under whose guidence this study was completed; Mr. P. A. Caraway, for his invaluable assistance in photography; Dr. D. W. Hayne and Mr. Poff, for their assistance in trapping; Dr. K. A. Stiles and Dr. R. H. Manville, for their helpful suggestions on various occasions; Mrs. Bernadette Henderson (Miss Mac), for her pleasant words of encouragement and advice; Dr. H. R. Hunt, head of the Zoology Department, for approval of the research problem; and Mr. N. J. Mizeres, for critically reading the manuscript. Special thanks is given to my wife for her assistance with the drawings and constant encouragement throughout the many months of work. -

Vessels and Circulation

CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM OUTLINE 23.1 Anatomy of Blood Vessels 684 23.1a Blood Vessel Tunics 684 23.1b Arteries 685 23.1c Capillaries 688 23 23.1d Veins 689 23.2 Blood Pressure 691 23.3 Systemic Circulation 692 Vessels and 23.3a General Arterial Flow Out of the Heart 693 23.3b General Venous Return to the Heart 693 23.3c Blood Flow Through the Head and Neck 693 23.3d Blood Flow Through the Thoracic and Abdominal Walls 697 23.3e Blood Flow Through the Thoracic Organs 700 Circulation 23.3f Blood Flow Through the Gastrointestinal Tract 701 23.3g Blood Flow Through the Posterior Abdominal Organs, Pelvis, and Perineum 705 23.3h Blood Flow Through the Upper Limb 705 23.3i Blood Flow Through the Lower Limb 709 23.4 Pulmonary Circulation 712 23.5 Review of Heart, Systemic, and Pulmonary Circulation 714 23.6 Aging and the Cardiovascular System 715 23.7 Blood Vessel Development 716 23.7a Artery Development 716 23.7b Vein Development 717 23.7c Comparison of Fetal and Postnatal Circulation 718 MODULE 9: CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM mck78097_ch23_683-723.indd 683 2/14/11 4:31 PM 684 Chapter Twenty-Three Vessels and Circulation lood vessels are analogous to highways—they are an efficient larger as they merge and come closer to the heart. The site where B mode of transport for oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, hor- two or more arteries (or two or more veins) converge to supply the mones, and waste products to and from body tissues. The heart is same body region is called an anastomosis (ă-nas ′tō -mō′ sis; pl., the mechanical pump that propels the blood through the vessels. -

The Cardiovascular System

11 The Cardiovascular System WHAT The cardiovascular system delivers oxygen and HOW nutrients to the body tissues The heart pumps and carries away wastes blood throughout the body such as carbon dioxide in blood vessels. Blood flow via blood. requires both the pumping action of the heart and changes in blood pressure. WHY If the cardiovascular system cannot perform its functions, wastes build up in tissues. INSTRUCTORS Body organs fail to function properly, New Building Vocabulary and then, once oxygen becomes Coaching Activities for this depleted, they will die. chapter are assignable in hen most people hear the term cardio- only with the interstitial fluid in their immediate Wvascular system, they immediately think vicinity. Thus, some means of changing and of the heart. We have all felt our own “refreshing” these fluids is necessary to renew the heart “pound” from time to time when we are ner- nutrients and prevent pollution caused by vous. The crucial importance of the heart has been the buildup of wastes. Like a bustling factory, the recognized for ages. However, the cardiovascular body must have a transportation system to carry system is much more than just the heart, and its various “cargoes” back and forth. Instead of from a scientific and medical standpoint, it is roads, railway tracks, and subways, the body’s important to understand why this system is so vital delivery routes are its hollow blood vessels. to life. Most simply stated, the major function of the Night and day, minute after minute, our tril- cardiovascular system is transportation. Using lions of cells take up nutrients and excrete wastes. -

Blood Vessels and Circulation

19 Blood Vessels and Circulation Lecture Presentation by Lori Garrett © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Section 1: Functional Anatomy of Blood Vessels Learning Outcomes 19.1 Distinguish between the pulmonary and systemic circuits, and identify afferent and efferent blood vessels. 19.2 Distinguish among the types of blood vessels on the basis of their structure and function. 19.3 Describe the structures of capillaries and their functions in the exchange of dissolved materials between blood and interstitial fluid. 19.4 Describe the venous system, and indicate the distribution of blood within the cardiovascular system. © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 19.1: The heart pumps blood, in sequence, through the arteries, capillaries, and veins of the pulmonary and systemic circuits Blood vessels . Blood vessels conduct blood between the heart and peripheral tissues . Arteries (carry blood away from the heart) • Also called efferent vessels . Veins (carry blood to the heart) • Also called afferent vessels . Capillaries (exchange substances between blood and tissues) • Interconnect smallest arteries and smallest veins © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 19.1: Blood vessels and circuits Two circuits 1. Pulmonary circuit • To and from gas exchange surfaces in the lungs 2. Systemic circuit • To and from rest of body © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 19.1: Blood vessels and circuits Circulation pathway through circuits 1. Right atrium (entry chamber) • Collects blood from systemic circuit • To right ventricle to pulmonary circuit 2. Pulmonary circuit • Pulmonary arteries to pulmonary capillaries to pulmonary veins © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. Module 19.1: Blood vessels and circuits Circulation pathway through circuits (continued) 3. Left atrium • Receives blood from pulmonary circuit • To left ventricle to systemic circuit 4. -

A Case of the Bilateral Superior Venae Cavae with Some Other Anomalous Veins

Okaiimas Fol. anat. jap., 48: 413-426, 1972 A Case of the Bilateral Superior Venae Cavae With Some Other Anomalous Veins By Yasumichi Fujimoto, Hitoshi Okuda and Mihoko Yamamoto Department of Anatomy, Osaka Dental University, Osaka (Director : Prof. Y. Ohta) With 8 Figures in 2 Plates and 2 Tables -Received for Publication, July 24, 1971- A case of the so-called bilateral superior venae cavae after the persistence of the left superior vena cava has appeared relatively frequent. The present authors would like to make a report on such a persistence of the left superior vena cava, which was found in a routine dissection cadaver of their school. This case is accompanied by other anomalies on the venous system ; a complete pair of the azygos veins, the double subclavian veins of the right side and the ring-formation in the left external iliac vein. Findings Cadaver : Mediiim nourished male (Japanese), about 157 cm in stature. No other anomaly in the heart as well as in the great arteries is recognized. The extracted heart is about 350 gm in weight and about 380 ml in volume. A. Bilateral superior venae cavae 1) Right superior vena cava (figs. 1, 2, 4) It measures about 23 mm in width at origin, about 25 mm at the pericardiac end, and about 31 mm at the opening to the right atrium ; about 55 mm in length up to the pericardium and about 80 mm to the opening. The vein is formed in the usual way by the union of the right This report was announced at the forty-sixth meeting of Kinki-district of the Japanese Association of Anatomists, February, 1971,Kyoto. -

Blood Vessels, Flow, and Regulation Overview of Circulation

Circulation: Blood Vessels, Flow, and Regulation Adapted From: Textbook Of Medical Physiology, 11th Ed. Arthur C. Guyton, John E. Hall Chapters 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, & 19 John P. Fisher © Copyright 2012, John P. Fisher, All Rights Reserved Overview of Circulation Introduction • Circulation allows transport of nutrients to the tissues, transport of waste away from the tissues, the movement of hormones, and the maintenance of fluid environment for overall survival and function of the cells • Overall circulation is divided into two portions • Systemic circulation • Pulmonary circulation © Copyright 2012, John P. Fisher, All Rights Reserved 1 Overview of Circulation Functional Parts of the Circulation • Arteries • Transport blood under high pressure • Arterioles • Acts as control valves through which blood is transported into the capillaries • Capillaries • Allows exchange of fluid, nutrients, electrolytes, hormones, and other substances • Venules • Collect blood from the capillaries • Veins • Conduits for transport of blood from tissues Guyton & Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology, back to the heart and reservoir of blood 11th Edition © Copyright 2012, John P. Fisher, All Rights Reserved Overview of Circulation Functional Parts of the Circulation Vessel CSA V RT Aorta 2.5 cm2 33 cm/sec Small arteries 20.0 cm2 Arterioles 40.0 cm2 Capillaries 2500.0 cm2 0.3 mm/sec 1 - 3 sec Venules 250.0 cm2 Small Veins 80.0 cm2 Venae cavae 8.0 cm2 Guyton & Hall. Textbook of Medical Physiology, 11th Edition © Copyright 2012, John P. Fisher, All Rights Reserved -

Cardiovascular System

Cardiovascular system Dr.jyoti kiran kohli • vascular system is transport system of body, through which nutrients are conveyed to places where they are utilized and waste products are then conveyed to appropriate place from where they are excreted. • it is a closed system of tubes made up of parts: • Heart, • Arteries, • veins & capilleries. • Heart—four chambered muscular organ which pumps blood to various parts of the body. • each half has a receiving chamber called atrium and a pumping chamber called ventricle. • arteries- distributing channels which carry blood away from heart, • they branch like trees on their way to different parts of the body. • the large arteries are rich in elastic tissue but as branching progress there is smooth muscle in their walls.the minute branches visible to naked eye are called arterioles. • veins—draining channels which carry blood from different parts of body to heart. • The venules( small veins ) join together to form larger veins which In turn unite to form great veins called venae cavae. • Capilleries—network of microscopic vessels which connect arterioles with venules.,they are in intimate contact with tissues for a free exchange of nutrients and metabolites across their walls b/w the blood and tissue fluid.,they are replaced by sinusoids in liver and spleen. • functionally classified into five groups: • distributing vessels—arteries • resistance vessels—arterioles, precapillary sphincters, • exchange vessels—capilleries, sinusoids, post capillery venules. • reservoir vessels—large venules,veins • shunts—various type of anastamosis. Types of circulation • systemic circulation • pulmonary circulation • Portal circulation Systemic circulation • left atrium ---- left ventricle ---to remote capilleries of body through aorta & its branches.-----------------------as nutrition & oxygen pass from blood to tissues ----through them waste products and co2 return from tissues to blood.-----------blood is then returned to heart through venules, vein, superior vena cava and inferior vena cava. -

S E C T I O N 9 . C a R D I O V a S C U L a R S Y S T

Section 9. Cardiovascular system 1 The heart (cor): is a hollow muscular organ possesses two atria possesses two ventricles is a parenchymatous organ is covered with adventitia 2 The human heart (cor) presents: apex (apex cordis) base (basis cordis) sternocostal surface (facies sternocostalis) pulmonary surface (facies pulmonalis) vertebral surface (facies vertebralis) 3 The grooves on the heart surface: coronary sulcus (sulcus coronarius) posterior interventricular sulcus (sulcus interventricularis posterior) anterior interventricular sulcus (sulcus interventricularis anterior) costal sulcus (sulcus costalis) anterior median sulcus(sulcus medianus anterior) 4 Coronary sulcus of the heart (sulcus coronarius): serves to be the outer border between atria (atria cordis) and ventricles (ventriculi cordis) contains the coronary vessels serves to be the outer border between the right and left atria (аtrium cordis dextrum/sinistrum) serves to be the outer border between the right and left ventricles (ventriculus cordis dexter/sinister) is proper to the pulmonary surface of heart (facies pulmonalis) 5 Heart auricles (auriculae): are constituent components of the right and left atrium (atrium dexter/sinister) are constituent components of the right and left ventricles (ventriculus dexter/ sinister) contain the papillary muscles contain the pectinate muscles participate in the base of heart 6 Anterior and posterior interventricular sulcuses (sulcus interventricularis anterior/posterior): connect at the apex of heart (apex cordis) connect at the -

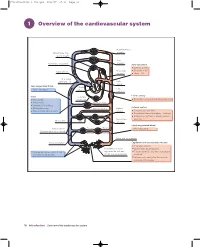

1 Overview of the Cardiovascular System

97814051150446_4_001.qxd 8/21/07 17:36 Page 10 1 Overview of the cardiovascular system Head and neck arteries Blood loses CO2, gains oxygen Arm arteries Pulmonary circulation Aortic pressure Systolic = 120 Diastolic = 80 Right atrium Bronchial arteries Mean = 93 Vena caval pressure = 0 Left atrium Less oxygenated blood Right Left ~70% saturated ventricle ventricle Elastic artery Veins Coronary Thin walled circulation Recoil helps propel blood during diastole Distensible Trunk arteries Contain 70% of blood Arterial system Blood reservoirs Hepatic artery Splenic Return blood to the heart artery Contains 17% of blood Distributes blood throughout the body Dampens pulsations in blood pressure Mesenteric and flow Portal vein Liver arteries Highly oxygenated blood Venous valves Efferent Afferent ~98% saturated (prevent backflux of blood) arterioles arterioles Pelvic and leg arteries Renal circulation Capillaries and postcapillary venules Exchange vessels Resistance arteries Blood loses O2 to tissues Venules and veins collect blood regulate flow of blood Tissues lose CO2 and waste products from exchange vessels to the exchange vessels to blood Immune cells can enter tissues via postcapillary venules 10 Introduction Overview of the cardiovascular system 97814051150446_4_001.qxd 8/21/07 17:36 Page 11 The cardiovascular system is composed of the heart, blood vessels and layer of overlapping endothelial cells, with no smooth muscle cells. The blood. In simple terms, its main functions are: pressure in the capillaries ranges from about 25 mmHg on the arterial 1 distribution of O2 and nutrients (e.g. glucose, amino acids) to all body side to 15 mmHg at the venous end. The capillaries converge into small tissues venules, which also have thin walls of mainly endothelial cells. -

Blood Vessels and Circulation

C h a p t e r 13 Blood Vessels and Circulation PowerPoint® Lecture Slides prepared by Jason LaPres Lone Star College - North Harris Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. 13-1 Arteries, arterioles, capillaries, venules, and veins differ in size, structure, and function Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Classes of Blood Vessels • Arteries – Carry blood away from the heart • Arterioles – Are the smallest branches of arteries • Capillaries – Are the smallest blood vessels – Location of exchange between blood and interstitial fluid • Venules – Collect blood from capillaries • Veins – Return blood to heart Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. The Structure of Vessel Walls • Tunica Intima – Innermost endothelial lining and connective tissue • Tunica Media – Is the middle layer – Contains concentric sheets of smooth muscle in loose connective tissue • Tunica Externa – Contains connective tissue sheath Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Typical Artery and a Typical Vein Figure 13-1 Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Arteries • From heart to capillaries, arteries change – From elastic arteries – To muscular arteries – To arterioles Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Arteries • Elastic Arteries – Also called conducting arteries – Large vessels (e.g., pulmonary trunk and aorta) – Tunica media has many elastic fibers and few muscle cells – Elasticity evens out pulse force Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Arteries • Muscular Arteries – Also called distribution arteries – Are medium sized (most arteries) – Tunica media has many muscle cells Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Arteries • Arterioles – Are small – Have little or no tunica externa – Have thin or incomplete tunica media Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. Blood Vessels Figure 13-2 Copyright © 2010 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Superior Vena Cava Pulmonary Trunk Aorta Parietal Pleura (Cut) Left Lung

Superior Aorta vena cava Parietal pleura (cut) Pulmonary Left lung trunk Pericardium (cut) Apex of heart Diaphragm (a) © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 1 Midsternal line 2nd rib Sternum Diaphragm Point of maximal intensity (PMI) (b) © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 Mediastinum Heart Right lung (c) Posterior © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 3 Pulmonary Fibrous trunk pericardium Parietal layer of serous pericardium Pericardium Pericardial cavity Visceral layer of serous pericardium Epicardium Myocardium Heart wall Endocardium Heart chamber © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 4 Superior vena cava Aorta Left pulmonary artery Right pulmonary artery Left atrium Right atrium Left pulmonary veins Right pulmonary veins Pulmonary semilunar valve Left atrioventricular valve Fossa ovalis (bicuspid valve) Aortic semilunar valve Right atrioventricular valve (tricuspid valve) Left ventricle Right ventricle Chordae tendineae Interventricular septum Inferior vena cava Myocardium Visceral pericardium (epicardium) (b) Frontal section showing interior chambers and valves © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 5 Left ventricle Right ventricle Muscular interventricular septum © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 6 Capillary beds of lungs where gas exchange occurs Pulmonary Circuit Pulmonary arteries Pulmonary veins Venae Aorta and cavae branches Left atrium Left Right ventricle atrium Heart Right ventricle Systemic Circuit Capillary beds of all body tissues where gas exchange occurs KEY: Oxygen-rich, CO2-poor blood Oxygen-poor, CO2-rich blood © 2018 Pearson Education, Inc. 7 (a) Operation of the AV valves 1 Blood returning 4 Ventricles contract, to the atria puts forcing blood against pressure against AV valve cusps. AV valves; the AV valves are forced open. 5 AV valves close. 2 As the ventricles 6 Chordae tendineae fill, AV valve cusps tighten, preventing hang limply into valve cusps from ventricles. -

Relationship Between Carcinoma and Thrombosis

CARCINOMA AND VENOUS THROMBOSIS: THE FREQUENCY OF ASSOCIATION OF CARCINOMA IN THE BODY OR TAIL OF THE PANCREAS WITH MULTIPLE VENOUS THROMBOSIS E. E. SPROUL, M.D. (Frm the Deportment of Pathology, Cohgs of Phyddwu ad Surgeons, Colvrnbh Udvsrdty) RELATIONSHIPBETWEEN CARCINOMAAND THROMBOSIS Text-books of medicine and of pathology often refer to the coincidence of a malignant tumor of epithelial origin and venous thrombosis. One of the earliest observers to stress this relationship was Trousseau (1) in 1865. He was especially interested in the frequency with which thrombosis of one or more peripheral veins was the first indication of the presence of a malignant tumor. Since his series of patients included those with tumors arising in the stomach, uterus, and testis, he concluded that the tendency to thrombosis was a characteristic of carcinoma in general and not dependent upon its origin in any particular organ. Recently Thomson @) quoted extensively from Trous- seau's original article and added a description of three cases in which the presenting disability was thrombosis of the veins of the leg. Examination after death showed a carcinoma arising in the tail of the pancreas in one of the patients, and of uncertain origin in another, A tumor of the stomach wall was demonstrated by x-ray studies in the third. Again emphasis was placed on the absence of any sign of internal disorder when the venous thrombosis was first apparent. In citing somewhat similar cases, James and Matheson (3) regarded thrombosis as an incident of the advanced stages of'a variety of debilitating diseases such as chronic infections, anemias, and malignant.