Gitlin Thesis 2018 FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acknowledgments 1 Background

NOTES Acknowledgments 1. Science and Science Policy in the Arab World , published by Centre for Arab Unity Studies 1979 and Croom Helm, 1980; and The Arab World and the Challenges of Science and Technology: Progress without Change , published by Centre for Arab Unity Studies, 1999. 1 Background 1. These numbers, as we shall see, are approximate. 2. “10 Emerging Technologies 2009,” Technology Review 102, 2 (April 2009), 37–54. 3. For a report on the ongoing debate in Germany on this issue, see Carter Dougherty, “Debate in Germany: Research or Manufacturing,” New York Times , August 12, 2009. 4. See Alvin and Heidi Toffler, Revolutionary Wealth (Currency Doubleday, 2006), 94. 5. Ibid., part 6, 146ff. 6. Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries: The Making of the Modern World (Grove Press, 2007). 7. It is speculated that the steam engine may have been invented earlier by Pharaonic priests and that knowledge of this invention was available to Hero of Alexandria at about 10 to 60 CE 8. It seems that cats became domesticated around 1450 BC and were used at that time to protect granaries in Egypt. See, for an interesting account of the cat in Egypt, Jaromir Malek, The Cat in Ancient Egypt (London: The British Museum Press, 2006), 54–55, Revised Edition. 9. Research concerning the conversion to steam shipping was already well under way. See Christine Macleod, Jeremy Stein, Jennifer Tann, and James Andrew, “Making Waves: The Royal Navy’s Management of Invention and Innovation in Steam Shipping, 1815–1832,” History and Technology , 16 (2000), 307–333. 10. Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (Allen Lane, 2007). -

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio Between the US and Syria

Song, State, Sawa Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Beau Bothwell All rights reserved ABSTRACT Song, State, Sawa: Music and Political Radio between the US and Syria Beau Bothwell This dissertation is a study of popular music and state-controlled radio broadcasting in the Arabic-speaking world, focusing on Syria and the Syrian radioscape, and a set of American stations named Radio Sawa. I examine American and Syrian politically directed broadcasts as multi-faceted objects around which broadcasters and listeners often differ not only in goals, operating assumptions, and political beliefs, but also in how they fundamentally conceptualize the practice of listening to the radio. Beginning with the history of international broadcasting in the Middle East, I analyze the institutional theories under which music is employed as a tool of American and Syrian policy, the imagined youths to whom the musical messages are addressed, and the actual sonic content tasked with political persuasion. At the reception side of the broadcaster-listener interaction, this dissertation addresses the auditory practices, histories of radio, and theories of music through which listeners in the sonic environment of Damascus, Syria create locally relevant meaning out of music and radio. Drawing on theories of listening and communication developed in historical musicology and ethnomusicology, science and technology studies, and recent transnational ethnographic and media studies, as well as on theories of listening developed in the Arabic public discourse about popular music, my dissertation outlines the intersection of the hypothetical listeners defined by the US and Syrian governments in their efforts to use music for political ends, and the actual people who turn on the radio to hear the music. -

A Comparison of Sawt Al-Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") and A1 Jazeera News Channel

The Development of Pan-Arab Broadcasting Under Authoritarian Regimes -A Comparison of Sawt al-Arab ("Voice of the Arabs") and A1 Jazeera News Channel Nawal Musleh-Motut Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of fistory O Nawal Musleh-Motut 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Approval Name: Nawal Musleh-Motut Degree: Master of Arts, History Title of Thesis: The Development of Pan-Arab Broadcasting Under Authoritarian Regimes - A Comparison of SdwzdArab ("Voice of the Arabs") and AI Jazeera News Channel Examining Committee: Chair: Paul Sedra Assistant Professor of History William L. Cleveland Senior Supervisor Professor of History - Derryl N. MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor of History Thomas Kiihn Supervisor Assistant Professor of History Shane Gunster External Examiner Assistant Professor of Communication Date Defended/Approved: fl\lovenh 6~ kg. 2006 UN~~ER~WISIMON FRASER I' brary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational -

Part of Imperial Communications: British-Governed Radio in the Middle East, 1934–1949

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Religious Studies 2013 Part of Imperial Communications: British-Governed Radio in the Middle East, 1934–1949 Andrea L. Stanton University of Denver, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/religious_studies_faculty Part of the Islamic World and Near East History Commons Recommended Citation Stanton, A. L. (2013). Part of imperial communications: British-governed radio in the Middle East, 1934-1949. Media History, 19(4), 421-435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2013.847141 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Part of Imperial Communications: British-Governed Radio in the Middle East, 1934–1949 Comments This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Media History on Oct. 15, 2013, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/13688804.2013.847141. Publication Statement Copyright held by the author or publisher. User is responsible for all copyright compliance. This article is available at Digital Commons @ DU: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/religious_studies_faculty/10 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Media History on Oct. 15, 2013, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/13688804.2013.847141. “Part of Imperial Communications”: British-Governed Radio in the Middle East, 1934-49 Abstract From 1934 to 1941, three British-governed radio stations were established in the Middle East: Egyptian State Broadcasting (ESB) in Cairo (1934), the Palestine Broadcasting Service (PBS) in Jerusalem (1936), and the Near East Broadcasting Service (NEBS) in Jaffa (1941). -

Pdf, (Consulted in June 2020)

Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique French Journal of British Studies XXVI-1 | 2021 The BBC and Public Service Broadcasting in the Twentieth Century BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad? Le Service arabe de la BBC, 1938-1995 : Soft Power ou pratique reithienne à l’étranger ? Houcine Msaddek Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/7056 DOI: 10.4000/rfcb.7056 ISSN: 2429-4373 Publisher CRECIB - Centre de recherche et d'études en civilisation britannique Electronic reference Houcine Msaddek, “BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad?”, Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique [Online], XXVI-1 | 2021, Online since 05 December 2020, connection on 05 January 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rfcb/7056 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ rfcb.7056 This text was automatically generated on 5 January 2021. Revue française de civilisation britannique est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad? 1 BBC Arabic (1938-1995): Soft Power or Reithian Practice Abroad? Le Service arabe de la BBC, 1938-1995 : Soft Power ou pratique reithienne à l’étranger ? Houcine Msaddek I dedicate this work in memory of my father who was a devoted listener of BBC Arabic in the nineteen-sixties and throughout the seventies. Introduction 1 BBC Arabic is both the largest and oldest of the British Broadcasting Corporation’s non- English language services. Launched in January 1938 in an almost direct response to Mussolini’s increasingly provocative anti-British Arabic language broadcasts aired from Bari, the Arabic Service of the BBC has constantly cultivated the loyalty of millions of listeners in the Middle East and North Africa ever since. -

The Origins of Kuwait's National Assembly

THE ORIGINS OF KUWAIT’S NATIONAL ASSEMBLY MICHAEL HERB LSE Kuwait Programme Paper Series | 39 About the Middle East Centre The LSE Middle East Centre opened in 2010. It builds on LSE’s long engagement with the Middle East and provides a central hub for the wide range of research on the region carried out at LSE. The Middle East Centre aims to enhance understanding and develop rigorous research on the societies, economies, polities, and international relations of the region. The Centre promotes both specialised knowledge and public understanding of this crucial area and has outstanding strengths in interdisciplinary research and in regional expertise. As one of the world’s leading social science institutions, LSE comprises departments covering all branches of the social sciences. The Middle East Centre harnesses this expertise to promote innovative research and training on the region. About the Kuwait Programme The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States is a multidisciplinary global research programme based in the LSE Middle East Centre and led by Professor Toby Dodge. The Programme currently funds a number of large scale col- laborative research projects including projects on healthcare in Kuwait led by LSE Health, urban form and infrastructure in Kuwait and other Asian cities led by LSE Cities, and Dr Steffen Hertog’s comparative work on the political economy of the MENA region. The Kuwait Programme organises public lectures, seminars and workshops, produces an acclaimed working paper series, supports post-doctoral researchers and PhD students and develops academic networks between LSE and Gulf institutions. The Programme is funded by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. -

The Italian Consulate in Jerusalem

The Italian unification is a long historical The Italian process that timidly started in 1815 after Consulate in the Congress of Vienna and culminated with the creation of the Kingdom of Italy Jerusalem: in 1861 and the capture of Rome in 1870.1 The Risorgimento followed a long and The History of a controversial path that brought together Forgotten Diplomatic people who shared history and culture, but also had been divided for centuries Mission, 1846–1940 and often involved in bitter disputes and Roberto Mazza, bloody wars. Diplomacy was at the heart of the creation of the Italian state that could Maria Chiara Rioli, and not have emerged on its own or throughout Stéphane Ancel war, however, Italian diplomatic missions outside Europe were fairly amateurish and often inconsequential. This article, divided in three sections, will discuss the establishment of an Italian consulate in Jerusalem, its activities and role from its opening to the end of the 1930s, prior to its temporary closure due to the outbreak of the Second World War. If the first part is substantially descriptive, the second part looks into the massive amount of archival material belonging to the Italian consulate in Jerusalem that was recently discovered and catalogued after having been misplaced for decades in the archives of the Italian Foreign Ministry. The last part briefly delves into a practical example of how this new material may be employed, looking at the Ethiopian community in Jerusalem. The overall aim of this relatively short piece is to bring back to life the history of the Italian consular mission in Jerusalem and, more importantly, to provide historians and researchers with a first overview on new perspectives from where investigating the recent past of the city and of Palestine. -

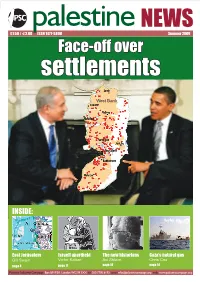

Face-Off Over Settlements

summer09 palestine NEWS 1 £1.50 / €2.00 ISSN 1477-5808 Summer 2009 Face-off over settlements West Bank INSIDE: East Jerusalem Israeli apartheid The new historians Gaza’s natural gas Gill Swain Victor Kattan Avi Shlaim Chris Cox page 4 page 11 page 14 page 18 Palestine Solidarity Campaign Box BM PSA London WC1N 3XX tel 020 7700 6192 email [email protected] web www.palestinecampaign.org 2 palestine NEWS summer09 Contents 3 Can Obama deliver? Betty Hunter examines the clash between Obama and Netanyahu over settlements 4 East Jerusalem — a stolen city Dramatic map reveals how settlements are spreading through Jerusalem 6 Q: Where are the Palestinian Ghandis? A: In Jail Bekah Wolf reports on a grassroots resistance movement — and the Israeli response 9 Trade unionists shocked and angry Kiri Tunks and Bernard Regan on a trade union delegation to the OPTs 10 BBC betrays Jeremy Bowen How the BBC Trust caved in to pressure and censured its Middle East editor Cover map: fmep_v18n1_map. pdf from the Foundation for 11 Israel guilty of colonialism and apartheid Middle East Peace. Victor Kattan on a hard-hitting South African report www.fmep.org 12 Dialogue with the Diaspora ISSN 1477 - 5808 Jeff Halper reflects on the reasons for the uproar he caused in Australia Also in this issue... 14 The ‘new history’ and the Nakba Gaza music school reopens Prof Avi Shlaim describes the impact of re-examining the past page 21 16 Operation ‘Hasbara’ Diane Langford examines how the Israeli propaganda machine manipulates the message 17 Between a rock and -

LILLY, EDWARD P.: Papers, 1928-1992

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS LILLY, EDWARD P.: Papers, 1928-1992 Accession: 01-10 and 02-15 Processed by: DJH Date Completed: November 2005 The Papers of Edward P. Lilly were deposited in the Eisenhower Library by his son Frank Lilly in two shipments in 2001 and 2002. The Library staff returned a small quantity of personal material to Mr. Frank Lilly at his request. Linear Feet: 24 Approximate Number of Pages: 46,100 Approximate Number of Items: 35,000 Mr. Frank Lilly signed an instrument of gift for the Papers of Edward P. Lilly on October 7, 1982. Literary rights in the unpublished writings of Edward P. Lilly in this collection and in any other collections of papers received by the United States government are given to the public. Under terms of the instrument of gift, the following classes of items are withheld from research use: 1. Papers and other historical materials the disclosure of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy of a living person. 2. Papers and other historical materials that are specifically authorized under criteria established by statute or executive order to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy, and are in fact properly classified pursuant to such statute or executive order. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Edward P. Lilly was born October 13, 1910 in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Joseph T. and Jennie Lilly. After graduating from Brooklyn Preparatory School in1928, Lilly attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts where he received a Bachelor’s of Arts degree with a major in philosophy and a minor in history. -

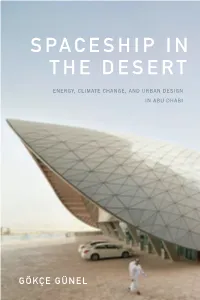

Spaceship in the Desert

SPACESHIP IN THE DESERT ENERGY, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND URBAN DESIGN IN ABU DHABI GÖKÇE GÜNEL SPACESHIP IN THE DESERT EXPERIMENTAL FUTURES Technological Lives, Scientifi c Arts, Anthropological Voices A series edited by Michael M. J. Fischer and Joseph Dumit Spaceship in the Desert Energy, Climate Change, and Urban Design in Abu Dhabi GÖKÇE GÜNEL Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro by Graphic Composition, Inc., Bogart, Georgia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Günel, Gökçe, [date] author. Title: Spaceship in the desert : energy, climate change, and urban design in Abu Dhabi / Gökçe Günel. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Series: Experimental futures | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifi ers: lccn 2018031276 (print) | lccn 2018041898 (ebook) isbn 9781478002406 (ebook) isbn 9781478000723 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478000914 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Sustainable urban development--United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) | City planning— Environmental aspects—United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) | Technological innovations— Environmental aspects—United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) | Urban ecology (Sociology) —United Arab Emirates—Abu Zaby (Emirate) Classifi cation: lcc ht243.u52 (ebook) | lcc ht243.u52 a28 2019 (print) ddc 307.1/16095357—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018031276 -

Britain and the Development of Professional Security Forces in the Gulf Arab States, 1921-71: Local Forces and Informal Empire

Britain and the Development of Professional Security Forces in the Gulf Arab States, 1921-71: Local Forces and Informal Empire by Ash Rossiter Submitted to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Arab and Islamic Studies February 2014 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Abstract Imperial powers have employed a range of strategies to establish and then maintain control over foreign territories and communities. As deploying military forces from the home country is often costly – not to mention logistically stretching when long distances are involved – many imperial powers have used indigenous forces to extend control or protect influence in overseas territories. This study charts the extent to which Britain employed this method in its informal empire among the small states of Eastern Arabia: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the seven Trucial States (modern day UAE), and Oman before 1971. Resolved in the defence of its imperial lines of communication to India and the protection of mercantile shipping, Britain first organised and enforced a set of maritime truces with the local Arab coastal shaikhs of Eastern Arabia in order to maintain peace on the sea. Throughout the first part of the nineteenth century, the primary concern in the Gulf for the British, operating through the Government of India, was therefore the cessation of piracy and maritime warfare. -

British Journal for Military History

British Journal for Military History Volume 6, Issue 3, November 2020 ‘Everybody to be armed’: Italian naval personnel and the Axis occupation of Bordeaux, 1940–1943 Alex Henry ISSN: 2057-0422 Date of Publication: 25 November 2020 Citation: Alex Henry, ‘‘Everybody to be armed’: Italian naval personnel and the Axis occupation of Bordeaux, 1940–1943’, British Journal for Military History, 6.3 (2020), pp. 23-41. www.bjmh.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The BJMH is produced with the support of ITALIAN NAVAL PERSONNEL AND THE AXIS OCCUPATION OF BORDEAUX ‘Everybody to be armed’: Italian naval personnel and the Axis occupation of Bordeaux, 1940– 1943 ALEX HENRY* The University of Nottingham, UK Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Bordeaux remains marked by ‘l’occupation’. Huge U-boat pens dominate the maritime districts of the city, an imposing reminder of the city's painful history. While such monuments maintain the memory of the German occupation, the Italian wartime presence in the city has been overlooked. Yet the Italian naval garrison had a huge influence on Bordeaux life. This article explores these relationships from the words of captured Italians, whose private conversations reveal how their actions were defined by violence and exploitation. This is a view of Italian soldiery that undermines the myth of the 'brava gente' – a people untainted by the brutality of war. There is an enduring popular perception of the Italian armed forces of