Dimensioning Rules

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles

NYS COMMON CORE MATHEMATICS CURRICULUM Lesson 3 M5 GEOMETRY Lesson 3: Rectangles Inscribed in Circles Student Outcomes . Inscribe a rectangle in a circle. Understand the symmetries of inscribed rectangles across a diameter. Lesson Notes Have students use a compass and straightedge to locate the center of the circle provided. If necessary, remind students of their work in Module 1 on constructing a perpendicular to a segment and of their work in Lesson 1 in this module on Thales’ theorem. Standards addressed with this lesson are G-C.A.2 and G-C.A.3. Students should be made aware that figures are not drawn to scale. Classwork Scaffolding: Opening Exercise (9 minutes) Display steps to construct a perpendicular line at a point. Students follow the steps provided and use a compass and straightedge to find the center of a circle. This exercise reminds students about constructions previously . Draw a segment through the studied that are needed in this lesson and later in this module. point, and, using a compass, mark a point equidistant on Opening Exercise each side of the point. Using only a compass and straightedge, find the location of the center of the circle below. Label the endpoints of the Follow the steps provided. segment 퐴 and 퐵. Draw chord 푨푩̅̅̅̅. Draw circle 퐴 with center 퐴 . Construct a chord perpendicular to 푨푩̅̅̅̅ at and radius ̅퐴퐵̅̅̅. endpoint 푩. Draw circle 퐵 with center 퐵 . Mark the point of intersection of the perpendicular chord and the circle as point and radius ̅퐵퐴̅̅̅. 푪. Label the points of intersection . -

Squaring the Circle a Case Study in the History of Mathematics the Problem

Squaring the Circle A Case Study in the History of Mathematics The Problem Using only a compass and straightedge, construct for any given circle, a square with the same area as the circle. The general problem of constructing a square with the same area as a given figure is known as the Quadrature of that figure. So, we seek a quadrature of the circle. The Answer It has been known since 1822 that the quadrature of a circle with straightedge and compass is impossible. Notes: First of all we are not saying that a square of equal area does not exist. If the circle has area A, then a square with side √A clearly has the same area. Secondly, we are not saying that a quadrature of a circle is impossible, since it is possible, but not under the restriction of using only a straightedge and compass. Precursors It has been written, in many places, that the quadrature problem appears in one of the earliest extant mathematical sources, the Rhind Papyrus (~ 1650 B.C.). This is not really an accurate statement. If one means by the “quadrature of the circle” simply a quadrature by any means, then one is just asking for the determination of the area of a circle. This problem does appear in the Rhind Papyrus, but I consider it as just a precursor to the construction problem we are examining. The Rhind Papyrus The papyrus was found in Thebes (Luxor) in the ruins of a small building near the Ramesseum.1 It was purchased in 1858 in Egypt by the Scottish Egyptologist A. -

P. 1 Math 490 Notes 7 Zero Dimensional Spaces for (SΩ,Τo)

p. 1 Math 490 Notes 7 Zero Dimensional Spaces For (SΩ, τo), discussed in our last set of notes, we can describe a basis B for τo as follows: B = {[λ, λ] ¯ λ is a non-limit ordinal } ∪ {[µ + 1, λ] ¯ λ is a limit ordinal and µ < λ}. ¯ ¯ The sets in B are τo-open, since they form a basis for the order topology, but they are also closed by the previous Prop N7.1 from our last set of notes. Sets which are simultaneously open and closed relative to the same topology are called clopen sets. A topology with a basis of clopen sets is defined to be zero-dimensional. As we have just discussed, (SΩ, τ0) is zero-dimensional, as are the discrete and indiscrete topologies on any set. It can also be shown that the Sorgenfrey line (R, τs) is zero-dimensional. Recall that a basis for τs is B = {[a, b) ¯ a, b ∈R and a < b}. It is easy to show that each set [a, b) is clopen relative to τs: ¯ each [a, b) itself is τs-open by definition of τs, and the complement of [a, b)is(−∞,a)∪[b, ∞), which can be written as [ ¡[a − n, a) ∪ [b, b + n)¢, and is therefore open. n∈N Closures and Interiors of Sets As you may know from studying analysis, subsets are frequently neither open nor closed. However, for any subset A in a topological space, there is a certain closed set A and a certain open set Ao associated with A in a natural way: Clτ A = A = \{B ¯ B is closed and A ⊆ B} (Closure of A) ¯ o Iτ A = A = [{U ¯ U is open and U ⊆ A}. -

Molecular Symmetry

Molecular Symmetry Symmetry helps us understand molecular structure, some chemical properties, and characteristics of physical properties (spectroscopy) – used with group theory to predict vibrational spectra for the identification of molecular shape, and as a tool for understanding electronic structure and bonding. Symmetrical : implies the species possesses a number of indistinguishable configurations. 1 Group Theory : mathematical treatment of symmetry. symmetry operation – an operation performed on an object which leaves it in a configuration that is indistinguishable from, and superimposable on, the original configuration. symmetry elements – the points, lines, or planes to which a symmetry operation is carried out. Element Operation Symbol Identity Identity E Symmetry plane Reflection in the plane σ Inversion center Inversion of a point x,y,z to -x,-y,-z i Proper axis Rotation by (360/n)° Cn 1. Rotation by (360/n)° Improper axis S 2. Reflection in plane perpendicular to rotation axis n Proper axes of rotation (C n) Rotation with respect to a line (axis of rotation). •Cn is a rotation of (360/n)°. •C2 = 180° rotation, C 3 = 120° rotation, C 4 = 90° rotation, C 5 = 72° rotation, C 6 = 60° rotation… •Each rotation brings you to an indistinguishable state from the original. However, rotation by 90° about the same axis does not give back the identical molecule. XeF 4 is square planar. Therefore H 2O does NOT possess It has four different C 2 axes. a C 4 symmetry axis. A C 4 axis out of the page is called the principle axis because it has the largest n . By convention, the principle axis is in the z-direction 2 3 Reflection through a planes of symmetry (mirror plane) If reflection of all parts of a molecule through a plane produced an indistinguishable configuration, the symmetry element is called a mirror plane or plane of symmetry . -

Descriptive Geometry Section 10.1 Basic Descriptive Geometry and Board Drafting Section 10.2 Solving Descriptive Geometry Problems with CAD

10 Descriptive Geometry Section 10.1 Basic Descriptive Geometry and Board Drafting Section 10.2 Solving Descriptive Geometry Problems with CAD Chapter Objectives • Locate points in three-dimensional (3D) space. • Identify and describe the three basic types of lines. • Identify and describe the three basic types of planes. • Solve descriptive geometry problems using board-drafting techniques. • Create points, lines, planes, and solids in 3D space using CAD. • Solve descriptive geometry problems using CAD. Plane Spoken Rutan’s unconventional 202 Boomerang aircraft has an asymmetrical design, with one engine on the fuselage and another mounted on a pod. What special allowances would need to be made for such a design? 328 Drafting Career Burt Rutan, Aeronautical Engineer Effi cient travel through space has become an ambi- tion of aeronautical engineer, Burt Rutan. “I want to go high,” he says, “because that’s where the view is.” His unconventional designs have included every- thing from crafts that can enter space twice within a two week period, to planes than can circle the Earth without stopping to refuel. Designed by Rutan and built at his company, Scaled Composites LLC, the 202 Boomerang aircraft is named for its forward-swept asymmetrical wing. The design allows the Boomerang to fl y faster and farther than conventional twin-engine aircraft, hav- ing corrected aerodynamic mistakes made previously in twin-engine design. It is hailed as one of the most beautiful aircraft ever built. Academic Skills and Abilities • Algebra, geometry, calculus • Biology, chemistry, physics • English • Social studies • Humanities • Computer use Career Pathways Engineers should be creative, inquisitive, ana- lytical, detail oriented, and able to work as part of a team and to communicate well. -

1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lines, and Planes

Understanding Points, 1-11-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Objectives Identify, name, and draw points, lines, segments, rays, and planes. Apply basic facts about points, lines, and planes. Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Vocabulary undefined term point line plane collinear coplanar segment endpoint ray opposite rays postulate Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes The most basic figures in geometry are undefined terms, which cannot be defined by using other figures. The undefined terms point, line, and plane are the building blocks of geometry. Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Points that lie on the same line are collinear. K, L, and M are collinear. K, L, and N are noncollinear. Points that lie on the same plane are coplanar. Otherwise they are noncoplanar. K L M N Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Example 1: Naming Points, Lines, and Planes A. Name four coplanar points. A, B, C, D B. Name three lines. Possible answer: AE, BE, CE Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Example 2: Drawing Segments and Rays Draw and label each of the following. A. a segment with endpoints M and N. N M B. opposite rays with a common endpoint T. T Holt Geometry 1-1 Understanding Points, Lines, and Planes Check It Out! Example 2 Draw and label a ray with endpoint M that contains N. -

Machine Drawing

2.4 LINES Lines of different types and thicknesses are used for graphical representation of objects. The types of lines and their applications are shown in Table 2.4. Typical applications of different types of lines are shown in Figs. 2.5 and 2.6. Table 2.4 Types of lines and their applications Line Description General Applications A Continuous thick A1 Visible outlines B Continuous thin B1 Imaginary lines of intersection (straight or curved) B2 Dimension lines B3 Projection lines B4 Leader lines B5 Hatching lines B6 Outlines of revolved sections in place B7 Short centre lines C Continuous thin, free-hand C1 Limits of partial or interrupted views and sections, if the limit is not a chain thin D Continuous thin (straight) D1 Line (see Fig. 2.5) with zigzags E Dashed thick E1 Hidden outlines G Chain thin G1 Centre lines G2 Lines of symmetry G3 Trajectories H Chain thin, thick at ends H1 Cutting planes and changes of direction J Chain thick J1 Indication of lines or surfaces to which a special requirement applies K Chain thin, double-dashed K1 Outlines of adjacent parts K2 Alternative and extreme positions of movable parts K3 Centroidal lines 2.4.2 Order of Priority of Coinciding Lines When two or more lines of different types coincide, the following order of priority should be observed: (i) Visible outlines and edges (Continuous thick lines, type A), (ii) Hidden outlines and edges (Dashed line, type E or F), (iii) Cutting planes (Chain thin, thick at ends and changes of cutting planes, type H), (iv) Centre lines and lines of symmetry (Chain thin line, type G), (v) Centroidal lines (Chain thin double dashed line, type K), (vi) Projection lines (Continuous thin line, type B). -

The Motion of Point Particles in Curved Spacetime

Living Rev. Relativity, 14, (2011), 7 LIVINGREVIEWS http://www.livingreviews.org/lrr-2011-7 (Update of lrr-2004-6) in relativity The Motion of Point Particles in Curved Spacetime Eric Poisson Department of Physics, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 email: [email protected] http://www.physics.uoguelph.ca/ Adam Pound Department of Physics, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 email: [email protected] Ian Vega Department of Physics, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 email: [email protected] Accepted on 23 August 2011 Published on 29 September 2011 Abstract This review is concerned with the motion of a point scalar charge, a point electric charge, and a point mass in a specified background spacetime. In each of the three cases the particle produces a field that behaves as outgoing radiation in the wave zone, and therefore removes energy from the particle. In the near zone the field acts on the particle and gives rise toa self-force that prevents the particle from moving on a geodesic of the background spacetime. The self-force contains both conservative and dissipative terms, and the latter are responsible for the radiation reaction. The work done by the self-force matches the energy radiated away by the particle. The field’s action on the particle is difficult to calculate because of its singular nature:the field diverges at the position of the particle. But it is possible to isolate the field’s singular part and show that it exerts no force on the particle { its only effect is to contribute to the particle's inertia. -

A Historical Introduction to Elementary Geometry

i MATH 119 – Fall 2012: A HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION TO ELEMENTARY GEOMETRY Geometry is an word derived from ancient Greek meaning “earth measure” ( ge = earth or land ) + ( metria = measure ) . Euclid wrote the Elements of geometry between 330 and 320 B.C. It was a compilation of the major theorems on plane and solid geometry presented in an axiomatic style. Near the beginning of the first of the thirteen books of the Elements, Euclid enumerated five fundamental assumptions called postulates or axioms which he used to prove many related propositions or theorems on the geometry of two and three dimensions. POSTULATE 1. Any two points can be joined by a straight line. POSTULATE 2. Any straight line segment can be extended indefinitely in a straight line. POSTULATE 3. Given any straight line segment, a circle can be drawn having the segment as radius and one endpoint as center. POSTULATE 4. All right angles are congruent. POSTULATE 5. (Parallel postulate) If two lines intersect a third in such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two right angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other on that side if extended far enough. The circle described in postulate 3 is tacitly unique. Postulates 3 and 5 hold only for plane geometry; in three dimensions, postulate 3 defines a sphere. Postulate 5 leads to the same geometry as the following statement, known as Playfair's axiom, which also holds only in the plane: Through a point not on a given straight line, one and only one line can be drawn that never meets the given line. -

Geometry Course Outline

GEOMETRY COURSE OUTLINE Content Area Formative Assessment # of Lessons Days G0 INTRO AND CONSTRUCTION 12 G-CO Congruence 12, 13 G1 BASIC DEFINITIONS AND RIGID MOTION Representing and 20 G-CO Congruence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Combining Transformations Analyzing Congruency Proofs G2 GEOMETRIC RELATIONSHIPS AND PROPERTIES Evaluating Statements 15 G-CO Congruence 9, 10, 11 About Length and Area G-C Circles 3 Inscribing and Circumscribing Right Triangles G3 SIMILARITY Geometry Problems: 20 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 1, 2, 3, Circles and Triangles 4, 5 Proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem M1 GEOMETRIC MODELING 1 Solving Geometry 7 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 Problems: Floodlights G4 COORDINATE GEOMETRY Finding Equations of 15 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 4, 5, Parallel and 6, 7 Perpendicular Lines G5 CIRCLES AND CONICS Equations of Circles 1 15 G-C Circles 1, 2, 5 Equations of Circles 2 G-GPE Expressing Geometric Properties with Equations 1, 2 Sectors of Circles G6 GEOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS AND DIMENSIONS Evaluating Statements 15 G-GMD 1, 3, 4 About Enlargements (2D & 3D) 2D Representations of 3D Objects G7 TRIONOMETRIC RATIOS Calculating Volumes of 15 G-SRT Similarity, Right Triangles, and Trigonometry 6, 7, 8 Compound Objects M2 GEOMETRIC MODELING 2 Modeling: Rolling Cups 10 G-MG Modeling with Geometry 1, 2, 3 TOTAL: 144 HIGH SCHOOL OVERVIEW Algebra 1 Geometry Algebra 2 A0 Introduction G0 Introduction and A0 Introduction Construction A1 Modeling With Functions G1 Basic Definitions and Rigid -

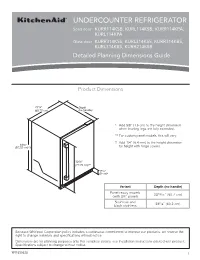

Dimension Guide

UNDERCOUNTER REFRIGERATOR Solid door KURR114KSB, KURL114KSB, KURR114KPA, KURL114KPA Glass door KURR314KSS, KURL314KSS, KURR314KBS, KURL314KBS, KURR214KSB Detailed Planning Dimensions Guide Product Dimensions 237/8” Depth (60.72 cm) (no handle) * Add 5/8” (1.6 cm) to the height dimension when leveling legs are fully extended. ** For custom panel models, this will vary. † Add 1/4” (6.4 mm) to the height dimension 343/8” (87.32 cm)*† for height with hinge covers. 305/8” (77.75 cm)** 39/16” (9 cm)* Variant Depth (no handle) Panel ready models 2313/16” (60.7 cm) (with 3/4” panel) Stainless and 235/8” (60.2 cm) black stainless Because Whirlpool Corporation policy includes a continuous commitment to improve our products, we reserve the right to change materials and specifications without notice. Dimensions are for planning purposes only. For complete details, see Installation Instructions packed with product. Specifications subject to change without notice. W11530525 1 Panel ready models Stainless and black Dimension Description (with 3/4” panel) stainless models A Width of door 233/4” (60.3 cm) 233/4” (60.3 cm) B Width of the grille 2313/16” (60.5 cm) 2313/16” (60.5 cm) C Height to top of handle ** 311/8” (78.85 cm) Width from side of refrigerator to 1 D handle – door open 90° ** 2 /3” (5.95 cm) E Depth without door 2111/16” (55.1 cm) 2111/16” (55.1 cm) F Depth with door 2313/16” (60.7 cm) 235/8” (60.2 cm) 7 G Depth with handle ** 26 /16” (67.15 cm) H Depth with door open 90° 4715/16” (121.8 cm) 4715/16” (121.8 cm) **For custom panel models, this will vary. -

13 Graphs 13.2D Lengths of Line Segments

MEP Pupil Text 13-19, Additional Material 13 Graphs 13.2D Lengths of Line Segments In a right-angled triangle the length of the hypotenuse may be calculated using Pythagoras' Theorem. c b cab222=+ a Worked Example 1 Determine the length of the line segment joining the points A (4, 1) and B (10, 9). Solution y (a) The diagram shows the two points and the line segment that joins them. 10 B A right-angled triangle has been 9 drawn under the line segment. The 8 length of the line segment AB (the 7 hypotenuse) may be found by using 6 Pythagoras' Theorem. 5 8 4 AB2 =+62 82 3 2 =+ 2 AB 36 64 A 6 1 AB2 = 100 0 12345678910 x AB = 100 AB = 10 Worked Example 2 y C Determine the length of the line 8 7 joining the points C (−48, ) 6 (−) and D 86, . 5 4 Solution 3 2 14 The diagram shows the two points 1 and a right-angled triangle that can –4 –3 –2 –1 0 12345678 x be used to determine the length of –1 the line segment CD. –2 –3 –4 –5 D –6 12 1 13.2D MEP Pupil Text 13-19, Additional Material Using Pythagoras' Theorem, CD2 =+142 122 CD2 =+196 144 CD2 = 340 CD = 340 CD = 18. 43908891 CD = 18. 4 (to 3 significant figures) Exercises 1. The diagram shows the three points y C A, B and C which are the vertices 11 of a triangle. 10 9 (a) State the length of the line 8 segment AB.