Merced Vision 2030 General Plan SCH# 2008071069

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

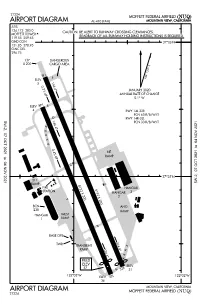

KNUQ Procedures

21224 MOFFETT FEDERAL AIRFIELD (NUQ) AIRPORT DIAGRAM AL-410 (FAA) MOUNTAIN VIEW, CALIFORNIA ATIS 124.175 283.0 CAUTION: BE ALERT TO RUNWAY CROSSING CLEARANCES. MOFFETT TOWER READBACK OF ALL RUNWAY HOLDING INSTRUCTIONS IS REQUIRED. 119.55 259.65 GND CON 37°26'N 121.85 278.95 CLNC DEL 296.75 137 DANGEROUS X 200 CARGO AREA E ° 3 . 3 14 1 L R F VA ELEV 144 5 0 . 3 4 % ° JANUARY 2020 U P ANNUAL RATE OF CHANGE 0.1° W 14 R ELEV E 4 RWY 14L-32R PCN 63 R/B/W/T D RWY 14R-32L SW-2, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV 144 PCN 33 R/B/W/T . 4 x ° x x x x 0 . 4 % NE U RAMP P C 37°25'N 211 Z SW-2, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV RAMP 8122 FIRE 9197 HANGAR STATION 3 X HANGAR 200 X 2 Y 200 BCN ANG 238 RAMP HANGAR WEST 1 RAMP B BASE OPS 324 TWR TRANSIENT x . 4 324 RAMP ° x . 4 x ° x FIELD ELEV ELEV 37 R A 32 31 122°03'W L 122°02'W ELEV 32 36 MOUNTAIN VIEW, CALIFORNIA AIRPORT DIAGRAM MOFFETT FEDERAL AIRFIELD (NUQ) 21224 (HOOKS2.HOOKS)21168 MOFFETT FEDERAL AIRFIELD (NUQ) HOOKS TWO DEPARTURE AL-410 (FAA) MOUNTAIN VIEW, CALIFORNIA ATIS TOP ALTITUDE: 124.175 283.0 ASSIGNED BY ATC CLNC DEL 296.75 GND CON 121.85 278.95 MOFFETT TOWER 119.55 (CTAF) 259.65 NORCAL DEP CON 120.1 290.25 MOFFETT Chan 123 NUQQUN (117.6) 141 ° SW-2, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV NOTE: TACAN required. -

United States of America Department of Transportation Office of the Secretary Washington, D.C

Order 2021-7-8 Served: July 16, 2021 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY WASHINGTON, D.C. Issued by the Department of Transportation On the 16th day of July, 2021 Essential Air Service at MERCED, CALIFORNIA DOCKET DOT-OST-1998-3521 (FAIN 69A3456021378)1 under 49 U.S.C. § 41731 et seq. ORDER EXTENDING CONTRACT Summary By this Order, the U.S. Department of Transportation (the Department) extends the terms of Order 2017-6-19 to the earlier of (i) December 31, 2021; or (ii) the conclusion of the current air carrier-selection case at Merced, California. Boutique Air, Inc. (Boutique Air) will continue to provide Essential Air Service (EAS) at Merced from August 1, 2021, through December 31, 2021. During the extension period, Boutique Air will continue to receive the existing annual subsidy rate and will operate the existing service pattern. Background By Order 2017-6-19 (June 26, 2017), the Department selected Boutique Air to provide EAS at Merced for the four-year period from August 1, 2017, through July 31, 2021. Under the terms of that Order, Boutique Air was selected to provide 19 nonstop round trips per week to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and 12 nonstop round trips per week to Oakland International Airport (OAK), using 8- or 9-seat Pilatus PC-12 aircraft, at the annual subsidy rates indicated below: Ye ar Subs idy Year 1$ 3,186,220 Year 2$ 3,249,944 Year 3$ 3,314,943 Year 4 $ 3,381,242 Total$ 13,132,349 1 Federal Award Identification Number (FAIN). -

Fishes As a Template for Reticulate Evolution

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America Max Russell Bangs University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Evolution Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Bangs, Max Russell, "Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1847. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1847 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fishes as a Template for Reticulate Evolution: A Case Study Involving Catostomus in the Colorado River Basin of Western North America A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biology by Max Russell Bangs University of South Carolina Bachelor of Science in Biological Sciences, 2009 University of South Carolina Master of Science in Integrative Biology, 2011 December 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _____________________________________ Dr. Michael E. Douglas Dissertation Director _____________________________________ ____________________________________ Dr. Marlis R. Douglas Dr. Andrew J. Alverson Dissertation Co-Director Committee Member _____________________________________ Dr. Thomas F. Turner Ex-Officio Member Abstract Hybridization is neither simplistic nor phylogenetically constrained, and post hoc introgression can have profound evolutionary effects. -

UNDERSTANDING REGIONAL CHARACTERISTICS California Adaptation Planning Guide

C A L I F O R N I A ADAPTATION PLANNING GUIDE UNDERSTANDING REGIONAL CHARACTERISTICS CALIFORNIA ADAPTATION PLANNING GUIDE Prepared by: California Emergency Management Agency 3650 Schriever Avenue Mather, CA 95655 www.calema.ca.gov California Natural Resources Agency 1416 Ninth Street, Suite 1311 Sacramento, CA 95814 resources.ca.gov WITH FUNDING Support From: Federal Emergency Management Agency 1111 Broadway, Suite 1200 Oakland, CA 94607-4052 California Energy Commission 1516 Ninth Street, MS-29 Sacramento, CA 95814-5512 WITH Technical Support From: California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 July 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Adaptation Planning Guide (APG) has benefited from the ideas, assessment, feedback, and support from members of the APG Advisory Committee, local governments, regional entities, members of the public, state and local non-governmental organizations, and participants in the APG pilot program. CALIFORNIA EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT AGENCY MARK GHILARDUCCI SECRETARY MIKE DAYTON UNDERSECRETARY CHRISTINA CURRY ASSISTANT SECRETARY PREPAREDNESS KATHY MCKEEVER DIRECTOR OFFICE OF INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION JOANNE BRANDANI CHIEF CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION DIVISION, HAZARD MITIGATION PLANNING DIVISION KEN WORMAN CHIEF HAZARD MITIGATION PLANNING DIVISION JULIE NORRIS SENIOR EMERGENCY SERVICES COORDINATOR HAZARD MITIGATION PLANNING DIVISION KAREN MCCREADY ASSOCIATE GOVERNMENT PROGRAM ANALYST HAZARD MITIGATION PLANNING DIVISION CALIFORNIA NATURAL RESOURCE AGENCY JOHN LAIRD SECRETARY JANELLE BELAND UNDERSECRETARY -

Lynchburg Regional Connectivity Study

Lynchburg Regional Connectivity Study Prepared for: Virginia Department of Transportation – Lynchburg District & Virginia Office of Intermodal Planning and Investment Prepared by: Economic Development Research Group, Inc. Michael Baker International and Renaissance Planning March 2, 2017 INSERT DUE DATE TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ 1 Approach .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Findings ............................................................................................................................................ 2 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 5 Motivation and Context ................................................................................................................... 5 Study Approach and Outcomes ....................................................................................................... 5 Report Organization ......................................................................................................................... 8 2. Lynchburg Regional Economy ................................................................................................. 9 Population Trends ........................................................................................................................... -

Lost River Sucker 5-Year Status Review

Lost River Sucker (Deltistes luxatus) 5-Year Review Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Klamath Falls Fish and Wildlife Office Klamath Falls, Oregon July 2007 5-YEAR REVIEW Lost River Sucker (Deltistes luxatus) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 GENERAL INFORMATION.......................................................................................... 1 1.1. Reviewers............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2. Methodology used to complete the review....................................................................... 1 1.3. Background ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 REVIEW ANALYSIS....................................................................................................... 2 2.1. Application of the 1996 Distinct Populations Segment (DPS) policy ............................ 2 2.2. Biology and Habitat ........................................................................................................... 3 2.3. Recovery Criteria............................................................................................................. 12 2.4. Five-Factor Analysis ........................................................................................................ 15 2.5. Synthesis............................................................................................................................ 29 3.0 RESULTS ....................................................................................................................... -

Introgressive Hybridization and the Evolution of Lake-Adapted Catostomid Fishes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Introgressive Hybridization and the Evolution of Lake-Adapted Catostomid Fishes Thomas E. Dowling1¤a*, Douglas F. Markle2, Greg J. Tranah3¤b, Evan W. Carson1¤c, David W. Wagman2¤d, Bernard P. May3 1 School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, United States of America, 2 Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, United States of America, 3 Department of Animal Science, University of California Davis, Davis, California, United States of America ¤a Current address: Department of Biological Sciences, Wayne State University, Detroit Michigan, United States of America ¤b Current address: California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States of America ¤c Current address: Biology Department and Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States of America ¤d Current address: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Newport, Oregon, United States of America * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Dowling TE, Markle DF, Tranah GJ, Carson EW, Wagman DW, May BP (2016) Introgressive Abstract Hybridization and the Evolution of Lake-Adapted Catostomid Fishes. PLoS ONE 11(3): e0149884. Hybridization has been identified as a significant factor in the evolution of plants as groups doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149884 of interbreeding species retain their phenotypic integrity despite gene exchange among Editor: Filippos A. Aravanopoulos, Aristotle forms. Recent studies have identified similar interactions in animals; however, the role of University of Thessaloniki, GREECE hybridization in the evolution of animals has been contested. Here we examine patterns of Received: October 15, 2015 gene flow among four species of catostomid fishes from the Klamath and Rogue rivers using molecular and morphological traits. -

PRESERVING MILITARY AVIATION HERITAGE Www

www.castleairmuseum.org CONTRAILS FALL 2019 - PRESERVING MILITARY AVIATION HERITAGE ON APPROACH By: Joe Pruzzo, CEO The Museum has been a beehive of activity thus far in 2019 on all fronts. Our beautiful Lockheed MC-130 P Hercules Aircraft was moved from the Castle Airport Tarmac area to the Museum this past July. As you can image this was quite an undertaking! Many Museum departments, plus municipalities and utility companies were involved to facilitate this move. Personally, and on behalf of the entire Museum thank you to all who participated to make this move a resounding success! The dedication of this aircraft was held on Saturday Oct. 26, 2019. While on the subject of grounds and facilities, they have never looked better! Thank you Tim, Larry, Ed, ADM-20 Quail Decoy Missle and Brian for all of your hard work and dedication. For the first time we took our television campaign North to the Sacramento market, while pouring more into our Fresno television campaign, which resulted in an Open Cockpit Day larger than ever experienced by the Museum! Aviation Pavilion to host events, both private and community Approximately 5,000 plus in attendance on Monday, yes events, along with the prospect of having the option of hosting Monday Memorial Day May 27. I must thank our exceptional traveling, cultural exhibits for our region and beyond. Our staff and volunteers for shifting the day from Sunday to marketing and promotion campaigns have been critical in the Monday, a mere 48 hours prior due to inclement weather. We growth of Museum awareness and getting more people to are diligently working towards our long desired goal of an come be amazed!! Hope to see you soon at the Museum! HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Moving the C130 HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH HANGAR HAPPENINGS By: Jeff Heyer, Restoration Manager all has welcomed us with some better weather, and a note I started in 2003 and restoration was a lot smaller group new set of 24 UC Merced inters for the semester. -

Merced County Regional Waste Management Authority Landfill-Gas-To-Energy Project

Initial Study/Proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration Merced County Regional Waste Management Authority Landfill-Gas-to-Energy Project June 2019 PREPARED FOR: Merced Regional Waste Management Authority Merced County Regional Waste Management Authority 7040 North Highway 59 Merced, California 95348 (209) 723-4481 Initial Study/Proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration for the Merced County Regional Waste Management Authority Landfill-Gas-to-Energy Project Prepared for: Merced Regional Waste Management Authority Merced County Regional Waste Management Authority 7040 North Highway 59 Merced, California 95348 (209) 723-4481 Contact: Jerry Lawrie, Environmental Resource Manager [email protected] Prepared By: Ascent Environmental, Inc. 455 Capitol Mall, Suite 300 Sacramento, California 95814 916/444-7301 Contact: Chris Mundhenk June 2019 18010098.02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................................................................................................... iii 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Introduction and Regulatory Guidance ................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Why this Document? .................................................................................................................................................... -

Intiial Study

UC MERCED DOWNTOWN CENTER PROJECT Final Initial Study and Mitigated Negative Declaration The following Initial Study has been prepared in compliance with CEQA. SCH NO. 2015041087 Prepared By: University of California, Merced 5200 North Lake Road Merced, CA 95343 June 2015 Contact: Phillip Woods, Director of Physical & Environmental Planning [email protected] Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Initial Study ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Public and Agency Review ......................................................................................................................... 1 Organization of the Initial Study ................................................................................................................ 2 1. PROJECT INFORMATION ......................................................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................ 5 2.1 Location ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Existing Conditions ....................................................................................................................... -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Oregon Fish and Wildlife Office 2600 SE 98th Avenue, Suite 100 Portland, Oregon 97266 Phone: (503) 231-6179 FAX: (503) 231-6195 Reply To: 8330.F0047(09) File Name: CREP BO 2009_final.doc TS Number: 09-314 TAILS: 13420-2009-F-0047 Doc Type: Final Don Howard, Acting State Executive Director U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Service Agency, Oregon State Office 7620 SW Mohawk St. Tualatin, OR 97062-8121 Dear Mr. Howard, This letter transmits the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (Service) Biological and Conference Opinion (BO) and includes our written concurrence based on our review of the proposed Oregon Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) to be administered by the Farm Service Agency (FSA) throughout the State of Oregon, and its effects on Federally-listed species in accordance with section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (Act) of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). Your November 24, 2008 request for informal and formal consultation with the Service, and associated Program Biological Assessment for the Oregon Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (BA), were received on November 24, 2008. We received your letter providing a 90-day extension on March 26, 2009 based on the scope and complexity of the program and the related species that are covered, which we appreciated. This Concurrence and BO covers a period of approximately 10 years, from the date of issuance through December 31, 2019. The BA also includes species that fall within the jurisdiction of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Fisheries Service (NOAA Fisheries Service). -

Chapter 2 - Draft October 2019

Delaware Aviation System Plan Chapter 2 - Draft October 2019 ANALYSIS OF EXISTING SYSTEM HE PURPOSE OF THIS CHAPTER IS TO provide the necessary database for subsequent phases of the System Plan. Pertinent data, regarding each airport/heliport and the area it serves was T collected from each airport and the appropriate State and local agencies. In addition to the data provided by these sources, information published by the Federal government and other sources required for comprehensive understanding of the existing aviation system was collected, tabulated, and reviewed. Maximum use was made of the existing system planning work, various existing airport master plans, and environmental studies that have been completed. From these data, the analysis of the existing system was developed. Inventory items included: Airport and Heliport Facilities Aeronautical Activity Fuel Sales by Airport Land Use Around System Airports Socioeconomic Base Statutes and Regulations Future Technology Of these items, the examination of State Aviation Regulations was used to determine whether an update is needed to accommodate funding for private airport development. 1. AIRPORT AND HELIPORT FACILITIES HE FACILITY INVENTORY RECORDS OF DELDOT (WHICH are used for the FAA Form 5010), were used as T one source of inventory data for airport and heliport facilities. Figure 2‐1 presents a map of Delaware showing the locations of each of the existing public‐use airports and heliports. Additional data and information were obtained through review of existing completed airport master plans, and those that are in progress. In addition to the data from published records, on‐site inspections of some of the system airports were necessary to inspect runway and taxiway pavement conditions.