Bridging the Centuries: a Brief Biography Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justifying Occupation?

Justifying Occupation? A strategic frame-analysis of the way India & Israel have rhetorically justified their military annexations (1961-1981) Abstract: Besides using military power to attain new territories, framing plays an important part in holding onto them, as it enables the occupier to ‘sell’ the idea of a new post- conflict reality. Using postcolonialism as background theory, this thesis researches what historical frames were used, and what the effect of these frames were on (1) the domestic audience of the occupying country, (2) the audience of the occupied territories, and (3) the international community. It looks at the annexation of Goa (1961) and the Golan Heights (1981) as similar design case studies, where the former was accepted by more audiences. Frames that refer to national identity and safeguarding the existential safety of the occupying country, proved to be most successful across the audiences to gather support, or avoid serious sanctions from the international community, during 1961-1981. Abdul Abdelaziz S 4211766 Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands. Master thesis International Relations Supervisor: prof. dr. Bertjan Verbeek 0 Date: June 28, 2020 Wordcount (excl. sources): 27661 “Occupation, curfew, settlements, closed military zone, administrative detention, siege, preventive strike, terrorist infrastructure, transfer. Their WAR destroys language. Speaks genocide with the words of a quiet technician. Occupation means that you cannot trust the OPEN SKY, or any open street near to the gates of a sniper’s tower. It means that you cannot trust the future or have faith that the past will always be there. Occupation means you live out your live under military rule, and the constant threat of death, a quick death from a sniper’s bullet or a rocket attack from an M16. -

If Goa Is Your Land, Which Are Your Stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home*

If Goa is your land, which are your stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home* Cielo Griselda Festinoa Abstract Goa, India, is a multicultural community with a broad archive of literary narratives in Konkani, Marathi, English and Portuguese. While Konkani in its Devanagari version, and not in the Roman script, has been Goa’s official language since 1987, there are many other narratives in Marathi, the neighbor state of Maharashtra, in Portuguese, legacy of the Portuguese presence in Goa since 1510 to 1961, and English, result of the British colonization of India until 1947. This situation already reveals that there is a relationship among these languages and cultures that at times is highly conflictive at a political, cultural and historical level. In turn, they are not separate units but are profoundly interrelated in the sense that histories told in one language are complemented or contested when narrated in the other languages of Goa. One way to relate them in a meaningful dialogue is through a common metaphor that, at one level, will help us expand our knowledge of the points in common and cultural and * This paper was carried out as part of literary differences among them all. In this article, the common the FAPESP thematic metaphor to better visualize the complex literary tradition from project "Pensando Goa" (proc. 2014/15657-8). The Goa will be that of the village since it is central to the social opinions, hypotheses structure not only of Goa but of India. Therefore, it is always and conclusions or recommendations present in the many Goan literary narratives in the different expressed herein are languages though from perspectives that both complement my sole responsibility and do not necessarily and contradict each other. -

Bowl Round 10 Bowl Round 10 First Quarter

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2015-2016 Bowl Round 10 Bowl Round 10 First Quarter (1) This country was the birthplace of the starting shortstop and first baseman for the 2015 Chicago White Sox, Alexei Ramirez and Jose Abreu. The names of players like Yunel Escobar and Yoenis Cespedes, begin with \Y," as inspired by this country's former ties with diplomats like Yuri Pavlov. For ten points, name this country from which Aroldis Chapman and Yasiel Puig defected, leaving behind the only Communist government in Latin America. ANSWER: Cuba (2) Potential violations of this law are considered using the \rule of reason" doctrine. The Danbury Hatters court case applied this law to labor unions, but it did not apply to manufacturing after the government failed in their suit against the E.C. Knight Company. The Standard Oil Company was broken up using, for ten points, what 1890 antitrust law, named for an Ohio senator and later modified by the Clayton Antitrust Act? ANSWER: Sherman Antitrust Act (3) This party engaged in frequent violent clashes against the Inkatha Freedom Party, and one leader defected from this party to form the Economic Freedom Fighters. This party's armed division, Umkhonto we Sizwe, was established in response to the Sharpeville massacre. This party first rose to power in 1994, defeating F.W. De Klerk's National Party. Jacob Zuma is the current leader of, for ten points, what anti-apartheid party in South Africa? ANSWER: African National Congress (accept Umkhonto we Sizwe before mentioned) (4) This artistic style dominates Frederick the Great's summer palace at Sanssouci. -

Indian Armed Forces:The Defence of Indian

INDIAN ARMED FORCES:THE DEFENCE OF INDIAN India a land of diversities as we all know which extends from various religions,regions,ethnicities,languages etc. And even has diversity in its topography such as the Himalayan ranges,the Indo-Gangetic plain,the Thar desert,the peninsular plateau,the coastal plains etc. To safeguard these various diversities of the Republic of India is the main role of the Armed Forces of India. Indian Armed Forces the stone pillars of India's defence. Armed forces consists of three professional uniformed services: the Indian army, the Indian air force and the Indian navy. And these services are supported by the Indian coastguards and the paramilitary forces such as CRPF,CISF,BSF,SSB,ITBP,NSG. The President of India is the formal supreme commander of the Armed Forces of India with its headquarters in New Delhi. The origin of the Indian Forces can be traced back from the British colonial periods. And the Royal Indian Navy was first being established. Indian contingents also take part in world wars along with the British army. In world war 2 Indian army become the largest volunteer army with 2.5 million men. Some of the notable officers during British colonial period were Kodandera M.Cariappa, S.M Shrinagesh and Kodandera Subayya Thimayya. After the Indian independence, the armed forces become a major player in safeguarding the national interest of Indians. Armed forces played a major role in 1961 annexation of goa through operation vijay. It also fought four major wars with Pakistan and China and also participated in various operations like operation Meghdoot, operation Pawan etc. -

Sr. II N O. 8 Ext. 2.Pmd

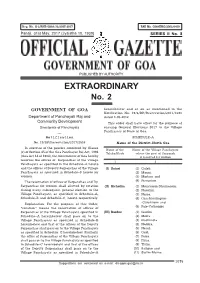

Reg. No. G-2/RNP/GOA/32/2015-2017 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 31st May, 2017 (Jyaistha 10, 1939) SERIES II No. 8 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY EXTRAORDINARY No. 2 GOVERNMENT OF GOA hereinbelow and so on as mentioned in the Notification No. 19/6/DP/Reservation/2011/1698 Department of Panchayati Raj and dated 8-05-2012. Community Development This order shall have effect for the purpose of Directorate of Panchayats ensuing General Elections 2017 to the Village __ Panchayats of State of Goa. Notification SCHEDULE–A No. 19/DP/Reservation/2017/2558 Name of the District–North Goa In exercise of the powers conferred by Clause Name of the Name of the Village Panchayats (c) of Section 45 of the Goa Panchayat Raj Act, 1994 Taluka/Block where the post of Sarpanch (Goa Act 14 of 1994), the Government of Goa hereby is reserved for women reserves the offices of Sarpanchas of the Village 12 Panchayats as specified in the Schedule–A hereto and the offices of Deputy Sarpanchas of the Village (I) Satari (1) Guleli. Panchayats as specified in Schedule–B hereto for (2) Mauxi. women. (3) Morlem and The reservation of offices of Sarpanchas and Dy. (4) Pissurlem. Sarpanchas for women shall allotted by rotation (II) Bicholim (1) Mencurem-Dhumacem. during every subsequent general election to the (2) Navelim. Village Panchayats, as specified in Schedule–A, (3) Naroa. Schedule–B and Schedule–C, hereto respectively. (4) Ona-Maulingem- -Curchirem and Explanation: For the purpose of this Order, (5) Pale-Cothombi. “rotation” means the reservation of offices of Sarpanchas of the Village Panchayats specified in (III) Bardez (1) Guirim. -

SSC CGL History PDF

SSC CGL History PDF 24 April 2018 TAKE CRACKU'S FREE SSC CGL MOCK Question 1: Who was the Governor General of India when the first war of Independence broke out in 1857? a) Lord Ripon b) Lord Napier c) Lord Lytton d) Lord Canning e) Lord Curzon Question 2: Whose quote is "Nehru is a patriot while Jinnah is a Politician."? a) Mahatma Gandhi b) Subhash Chandra Bose c) Abdul Gaffer Khan d) Mohammad Iqbal e) Sardar Vallabhai Patel Question 3: Who was the first to describe the 1857 mutiny as the first war of independence? a) Bal Gangadhar Tilak b) Lala Lajpat Rai c) Veer Savarkar d) Rabindranath Tagore e) Mahatma Gandhi Question 4: Who was the world’s first woman prime minister? a) Margaret Thatcher b) Indira Gandhi c) Sirimavo Bandaranaike d) Golda Meir e) Elisabeth Domitien SSC CGL Syllabus 2018 PDF SSC CGL Free Previous Papers Download Our App FREE PAST SSC CGL PAPERS Question 5: In which year did the first non-Cooperation Movement start in India? a) 1907 b) 1919 c) 1920 d) 1921 e) 1930 Question 6: In which year did Mahatma Gandhi go to South Africa for the first time? a) 1889 b) 1893 c) 1895 d) 1897 e) 1903 Question 7: Who was the first president of the Indian National Congress? a) WC Banerjee b) A.O. Hume c) Dadabhai Naoroji d) Gopal Krishna Gokhale e) Motilal Nehru Question 8: Who is the longest serving President of the Indian National Congress? a) Jawahar Lal Nehru b) U.N. Dhebar c) K. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Wonderful Goa - Golden sun, white sands and local cuisines The programme Come to Goa to unwind on its white sand beaches, simply relax and soak in the sun while tasting some bites of the delicious Goan cuisine and seafood. Don’t miss Old Goa with its stunning cathedrals and architecture that witness the glorious Portuguese past of Goa. The Experiences Explore the white sand beaches of Goa Enjoy water sports like boating, parasailing, banana rides and Jet Ski Explore the famous nightclubs of Goa Visit Dudhsagar waterfalls Tour the churches of Goa Discover Loutolim, an old town where Hindus and Christians live in harmony Visit the flea markets of Goa Wonderful Goa - Golden sun, white sands and local cuisines The Experiences | Day 01: Arrive Goa Welcome to India! On arrival at Goa Airport, you will be greeted by our tour representative in the arrival hall, who will escort you to your hotel and assist you in check-in. Kick off your holiday unwinding on the golden sand beaches of Goa. Laze around at Calangute Beach and Candolim Beach and enjoy the delightful Goan cuisine. Goa is famous for its seafood, including deliciously cooked crabs, prawns, squids, lobsters and oysters. The influence of Portuguese on Indian cuisine can best be explored here. As an ex-colony, Goa still retains Portuguese influences even today. Soak up the sunset panorama at Baga Beach - a crowded beach that comes to life at twilight. Spend a few hours by candle light and enjoy drinks and dinner with the sound of gushing waves in the background. -

CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction 1 2. Functions of the Directorate Of

I N D E X CONTENTS PAGE NO. 1. Introduction 1 2. Functions of the Directorate of Official Language 2 3. Steps initiated to implement the Official Language Act 3 – 4 4. Analysis & Recommendations 5 5. Plan Schemes 6 – 9 - 1 - 1. Introduction : In accordance with the Government of Goa, the Directorate of Official Language was established in 2004 as an independent Department of Government of Goa and entrusted with the nodal responsibility for all matters relating to the progressive use of Konkani as the Official Language of the State of Goa. As per the Government the Directorate adopted Konkani as the Official Language of the then Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu and accordingly the Goa, Daman and Diu Official Language Act 1987 (Act 5 of 1987) was enacted in pursuance of Section 34 of the Government of Union Territories Act, 1963 (Central Act 20 of 1963), Official Language Act 1987 which provides Konkani shall be the Official Language whereas, Marathi shall be used for all or any of the Official purposes. The Act envisaged the continuance of the English language of for official purposes in addition to Konkani & Marathi languages. - 2 - 2. Functions of the Directorate of Official Language : Its main functions include, inter-alia, the following : i. Enhancing the efficacy of Official language the Department releases recurring grants in aid to Goa Konkani Akademi. The Goa Konkani Akademi was established by the Government of Goa in the year 1984. ii. Recurring Grants in aid to Gomantak Marathi Academy for promoting Marathi language. The Gomantak Marathi Academy is an autonomous, sovereign Institution and was registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, bearing registration No. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

S Goesas Em Konkani Songs From

GOENCHIM KONKNI GAIONAM 1 CANÇO?S GOESAS EM KONKANI2 SONGS FROM GOA IN KONKANI 1 Konkani 2 Portuguese 1 Goans spoke Portuguese but sang in Konkani, a language brought to Goa by the Indian Arya. + A Goan way of expressing love: “Xiuntim mogrim ghe rê tuka, Sukh ani sontos dhi rê maka.” These Chrysanthemum and Jasmine flowers I give to thee, Joy and happiness give thou to me. 2 Bibliography3 A selection as background information Refer to Pereira, José / Martins, Micael. “Goa and its Music”, in: UUUUBoletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Nr.155 (1988) pp. 41-72 (Bibliography 43-55) for an extensive selection and to the Mando Festival Programmes published by the Konkani Bhasha Mandal in Panaji for recent compositions. Almeida, Mathew . 1988. Konkani Orthography. Panaji: Dalgado Konknni Akademi. Barreto, Lourdinho. 1984. Goemchem Git. Pustok 1 and 2. Panaji: Pedro Barreto, Printer. Barros de, Joseph. 1989. “The first Book to be printed in India”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 159. pp. 5-16. Barros de, Joseph. 1993. “The Clergy and the Revolt in Portuguese Goa”, in: Boletim do Instituto Menezes Bragança, Panaji. Tip. Rangel, Bastorá. Nr. 169. pp. 21-37. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). 2000. Goa and Portugal. History and Development. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Borges, Charles J. (ed.). Goa´s formost Nationalist: José Inácio Candido de Loyola. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. (Loyola is mentioned in the mando Setembrachê Ekvissavêru). Bragança, Alfred. 1964. “Song and Music”, in: The Discovery of Goa. Panaji: Casa J.D. Fernandes. pp. 41-53. Coelho, Victor A. -

The Denationalisation of Goans

Nishtha DESAI, Lusotopie 2000 : 469-476 The Denationalisation of Goans An Insight into the Construction of Cultural Identity* ristao de Braganza Cunha (1891-1958)1, henceforth referred to as Cunha, authored an essay, The Denationalization of Goans, published in T1944 as a booklet2. This essay gives a sharp critique of the psy- chological dominance of Portuguese culture over the educated people of Goa. It gives an insight into the construction of identities in the context of Portuguese colonial rule from the standpoint of an Indian nationalist. This is the subject matter of this presentation. Cunha, constructed a thesis of denationalisation, identifying it as the main obstacle for the development of nationalism in Goa. As a result of this essay, the term « denationalisation » entered the vocabulary of almost every freedom fighter in Goa. The Use of the Term « Denationalisation » It is not clear how Cunha came to use the term « denationalisation ». It was not a popularly used term, but one has come across being used in two different ways. Keshab Chandra Sen and Aurobindo Ghose have used the term to describe the efforts of the British to alienate the Indian people from their own culture3. The Portuguese state used it to denote those who expressed any dissent against it. In 1914, arguing in favour of imparting primary education in the mother-tongue, konkani, rather than Portuguese, Menezes Braganza asserted that it was the perceived « danger of * This paper contains ideas from my doctoral thesis, Tombat, Nishtha (alias Nishtha Desai), Tristao de Braganza-Cunha (1891-1958) and the Rise of Nationalist Consciousness in Goa, Dept of Sociology, Goa University, February 1995.