Exploring the Stigmatization of Anorexia: a Focus on the Structural, Interpersonal, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

Deinstitutionalization: Its Impact on Community Mental Health Centers and the Seriously Mentally Ill Stephen P

Page 40 Deinstitutionalization: Its Impact on Community Mental Health Centers and the Seriously Mentally Ill Stephen P. Kliewer Melissa McNally Robyn L. Trippany Walden University Abstract Deinstitutionalization has had a significant impact on the mental health system, including the client, the agency, and the counselor. For clients with serious mental illness, learning to live in a community setting poses challenges that are often difficult to overcome. Community mental health agencies must respond to these specific needs, thus requiring a shift in how services are delivered and how mental health counselors need to be trained. The focus of this article is to explore the dynamics and challenges specific to deinstitution- alization, discuss implications for counselors, and identify solutions to respond to the identified challenges and resulting needs. State run psychiatric hospitals have traditionally been the primary component in the treatment of people with severe and persistent mental illness. For many years, individuals with severe mental illness (SMI) were kept out of the community setting. This isolation occurred for many reasons: a) the attitude of the public about people with mental illness, b) a belief that the mentally ill could only be helped in such settings, and c) a lack of resources at the community level (Patrick, Smith, Schleifer, Morris & McClennon, 2006). However, the institutional approach was not without its problems. A primary problem was the absence of hope and expecta- tion that patients would recover (Patrick, et al., 2006). In short, institutions seemed to become warehouses where mentally ill were kept for long periods of time with little expectation of improvement. -

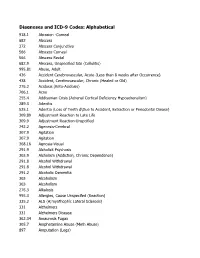

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings. -

Why Do We Need a Social Psychiatry? Antonio Ventriglio, Susham Gupta and Dinesh Bhugra

The British Journal of Psychiatry (2016) 209, 1–2. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.175349 Editorial Why do we need a social psychiatry? Antonio Ventriglio, Susham Gupta and Dinesh Bhugra Summary interventions in psychiatry should be considered in the Human beings are social animals, and familial or social framework of social context where patients live and factors relationships can cause a variety of difficulties as well as they face on a daily basis. providing support in our social functioning. The traditional way of looking at mental illness has focused on abnormal Declaration of interest thoughts, actions and behaviours in response to internal D.B. is President of the World Psychiatric Association. causes (such as biological factors) as well as external ones such as social determinants and social stressors. We Copyright and usage contend that psychiatry is social. Mental illness and B The Royal College of Psychiatrists 2016. and difficulties at these levels can lead to psychopathological Antonio Ventriglio (pictured) is an honorary researcher at the Department of and behavioural dysfunctions. Social stressors can lead to changes Clinical and Experimental Medicine at the University of Foggia, Italy. Susham 5 Gupta is a consultant psychiatrist at the East London Mental Health in the cerebral structure and affect neuro-hormonal pathways. Foundation NHS Trust. Dinesh Bhugra is Emeritus Professor of Mental Health Even organic conditions such as dementia are said to be related to & Cultural Diversity at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, life events and social factors such as economic and educational status.5 King’s College London and is President of the World Psychiatric Association. -

Standpoints on Psychiatric Deinstitutionalization Alix Rule Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre

Standpoints on Psychiatric Deinstitutionalization Alix Rule Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Alix Rule All rights reserved ABSTRACT Standpoints on Psychiatric Deinstitutionalization Alix Rule Between 1955 and 1985 the United States reduced the population confined in its public mental hospitals from around 600,000 to less than 110,000. This dissertation provides a novel analysis of the movement that advocated for psychiatric deinstitutionalization. To do so, it reconstructs the unfolding setting of the movement’s activity historically, at a number of levels: namely, (1) the growth of private markets in the care of mental illness and the role of federal welfare policy; (2) the contested role of states as actors in driving the process by which these developments effected changes in the mental health system; and (3) the context of relevant events visible to contemporaries. Methods of computational text analysis help to reconstruct this social context, and thus to identify the closure of key opportunities for movement action. In so doing, the dissertation introduces an original method for compiling textual corpora, based on a word-embedding model of ledes published by The New York Times from 1945 to the present. The approach enables researchers to achieve distinct, but equally consistent, actor-oriented descriptions of the social world spanning long periods of time, the forms of which are illustrated here. Substantively, I find that by the early 1970s, the mental health system had disappeared from public view as a part of the field of general medicine — and with it a target around which the existing movement on behalf of the mentally ill might have effectively reorganized itself. -

Dsm-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Eating Disorders Anorexia Nervosa

DSM-5 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR EATING DISORDERS ANOREXIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA To be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa according to the DSM-5, the following criteria must be met: 1. Restriction of energy intaKe relative to requirements leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. 2. Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even though underweight. 3. Disturbance in the way in which one's body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or denial of the seriousness of the current low body weight. Even if all the DSM-5 criteria for anorexia are not met, a serious eating disorder can still be present. Atypical anorexia includes those individuals who meet the criteria for anorexia but who are not underweight despite significant weight loss. Research studies have not found a difference in the medical and psychological impacts of anorexia and atypical anorexia. BULIMIA NERVOSA DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA According to the DSM-5, the official diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa are: • Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: o Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. within any 2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during a similar period of time and under similar circumstances. o A sense of lacK of control over eating during the episode (e.g. a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). -

Reading List

Psychiatric Epidemiology Dr. William W. Eaton Textbook Tsuang MT & Tohen M. Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, Wiley-Liss, 2002. Available online at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/booktoc/104527540 Session 1 Topic: Introduction, Nosology, and History of Psychiatric Epidemiology Assigned Readings: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). 4th ed. Washington, DC, APA Introduction, XV-XXV. Use of the manual, 1-11. Multiaxial Assessment, 25-35. Available online at: http://online.statref.com/TOC.aspx?grpalias=JHU&FxId=37 Recommended Additional Readings: o Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). 4th ed. Washington, DC, APA. o Choose any other single chapter on mental disorders. Session 2 Topic: Measurement of Psychopathology in Populations Assigned Readings: Tsuang, M.T.& Cohen, M. (2002). Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Wiley- Liss. Ch12. Murphy JM. Symptom scales and diagnostic schedules in adult psychiatry. 273-332. Recommended Additional Readings: Choose one Tsuang, M.T.& Cohen, M. (2002). Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Wiley- Liss. o Ch 9. Eaton, WW. Studying the Natural History of Psychopathology. 215-238. o Ch 11. Robins, LN. Birth and development of psychiatric interviews. 257-272. o Ch 14. Kessler RC and Walters E. The National Comorbidity Survey. 343-362. Session 3 Topic: Epidemiology of Anxiety Disorders Assigned Readings: Tsuang, M.T.& Cohen, M. (2002). Textbook in Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Wiley- Liss. Ch16. Horwath E, Cohen RS, Weissman MM. Epidemiology of depressive and anxiety disorders. 389-426 Recommended Additional Readings: Choose one o Eaton, W.W. (1995) Progress in the epidemiology of anxiety disorders. -

Patients' and Carers' Perspectives of Psychopharmacological

Chapter Patients’ and Carers’ Perspectives of Psychopharmacological Interventions Targeting Anorexia Nervosa Symptoms Amabel Dessain, Jessica Bentley, Janet Treasure, Ulrike Schmidt and Hubertus Himmerich Abstract In clinical practice, patients with anorexia nervosa (AN), their carers and clini- cians often disagree about psychopharmacological treatment. We developed two corresponding questionnaires to survey the perspectives of patients with AN and their carers on psychopharmacological treatment. These questionnaires were dis- tributed to 36 patients and 37 carers as a quality improvement project on a specialist unit for eating disorders at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Although most patients did not believe that medication could help with AN, the majority thought that medication for AN should help with anxiety (61.1%), con- centration (52.8%), sleep problems (52.8%) and anorexic thoughts (55.6%). Most of the carers shared the view that drug treatment for AN should help with anxiety (54%) and anorexic thoughts (64.8%). Most patients had concerns about potential weight gain, increased appetite, changes in body shape and metabolism during psychopharmacological treatment. By contrast, the majority of carers were not concerned about these specific side effects. Some of the concerns expressed by the patients seem to be AN-related. However, their desire for help with anxiety and anorexic thoughts, which is shared by their carers, should be taken seriously by clinicians when choosing a medication or planning psychopharmacological studies. Keywords: anorexia nervosa, psychopharmacological treatment, treatment effects, side effects, opinion survey, patients, carers 1. Introduction 1.1 Anorexia nervosa Anorexia nervosa (AN) is an eating disorder. According to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1], its diagnostic criteria are significantly low body weight, intense fear of weight gain, and disturbed body perception. -

Clinically Useful Brain Imaging for Neuropsychiatry: How Can We Get There?

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/115097; this version posted March 9, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Clinically Useful Brain Imaging for Neuropsychiatry: How Can We Get There? Michael P. Milham1,2, R. Cameron Craddock1,2 and Arno Klein1 1Center for the Developing Brain, Child Mind Institute, New York, NY 2Center for Biomedical Imaging and Neuromodulation, Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, New York, NY Corresponding Author: Michael P. Milham, MD, PhD Phyllis Green and Randolph Cowen Scholar Child Mind Institute 445 Park Avenue New York, NY 10022 [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/115097; this version posted March 9, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Despite decades of research, visions of transforming neuropsychiatry through the development of brain imaging-based ‘growth charts’ or ‘lab tests’ have remained out of reach. In recent years, there is renewed enthusiasm about the prospect of achieving clinically useful tools capable of aiding the diagnosis and management of neuropsychiatric disorders. The present work explores the basis for this enthusiasm. We assert that there is no single advance that currently has the potential to drive the field of clinical brain imaging forward. -

(Tdcs) for Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder White Paper

White paper Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for treatment of major depressive disorder Mode of action Brain stimulation with tDCS can be used to induce chang- In brief es in neuronal excitability in a polarity-dependent manner: positive anodal stimulus increases cortical excitability (de- • Non-invasive tDCS relieves symptoms in polarization) without triggering action potentials, whereas depressed patients by modulating cortical negative cathodal stimulus decreases excitability (hyperpo- excitability through a weak current larization)4 (Figure 1). To date, several studies have demon- strated hypoactivity of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex • tDCS can be used both as a monotherapy (DLPFC) in depressed patients.7,8 Accordingly, the antide- or as an adjunct to antidepressant pressant effects of tDCS may be due to the increased excit- medication and psychotherapy ability of the DLPFC, which further balances the left-right prefrontal activity and subsequently leads to symptom relief • Meta-analyses have found active tDCS in depressed patients.3 treatment to be significantly superior to sham tDCS in depressed patients Neurobiological studies have demonstrated that tDCS me- diates a cascade of events at a cellular and molecular level, • tDCS is well tolerated, and no serious including effects on the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors.9,10 side effects have been reported In addition to acute transient membrane potential chang- es that can last up to one hour, tDCS is associated with longer-lasting synaptic changes.11–12 Further studies eluci- dating the detailed mechanism of tDCS in therapeutic neu- romodulation are currently ongoing. Major depressive disorder (MDD) has an estimated life- time prevalence of 8–12% and is associated with signifi- cant morbidity and mortality.1 Standard treatments for Cathodal Anodal MDD include psychological therapies and antidepressant electrode (-) electrode (+) medication, which are often only moderately effective and Decreased neuronal Increased neuronal may have adverse effects.