Tense and Aspects in Tyap and English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Economic Origins of Constraints on Women's Sexuality

On the Economic Origins of Constraints on Women’s Sexuality Anke Becker* November 5, 2018 Abstract This paper studies the economic origins of customs aimed at constraining female sexuality, such as a particularly invasive form of female genital cutting, restrictions on women’s mobility, and norms about female sexual behavior. The analysis tests the anthropological theory that a particular form of pre-industrial economic pro- duction – subsisting on pastoralism – favored the adoption of such customs. Pas- toralism was characterized by heightened paternity uncertainty due to frequent and often extended periods of male absence from the settlement, implying larger payoffs to imposing constraints on women’s sexuality. Using within-country vari- ation across 500,000 women in 34 countries, the paper shows that women from historically more pastoral societies (i) are significantly more likely to have under- gone infibulation, the most invasive form of female genital cutting; (ii) are more restricted in their mobility, and hold more tolerant views towards domestic vio- lence as a sanctioning device for ignoring such constraints; and (iii) adhere to more restrictive norms about virginity and promiscuity. Instrumental variable es- timations that make use of the ecological determinants of pastoralism support a causal interpretation of the results. The paper further shows that the mechanism behind these patterns is indeed male absenteeism, rather than male dominance per se. JEL classification: I15, N30, Z13 Keywords: Infibulation; female sexuality; paternity uncertainty; cultural persistence. *Harvard University, Department of Economics and Department of Human Evolutionary Biology; [email protected]. 1 Introduction Customs, norms, and attitudes regarding the appropriate behavior and role of women in soci- ety vary widely across societies and individuals. -

Evaluation of the Performance of Ginger (Zingiber Officinale Rosc.) Germplasm in Kaduna State, Nigeria

Science World Journal Vol. 15(No 3) 2020 www.scienceworldjournal.org ISSN 1597-6343 Published by Faculty of Science, Kaduna State University https://doi.org/10.47514/swj/15.03.2020.019 EVALUATION OF THE PERFORMANCE OF GINGER (ZINGIBER OFFICINALE ROSC.) GERMPLASM IN KADUNA STATE, NIGERIA Sodangi, I. A. Full Length Research Article Department of Crop Science Kaduna State University *Corresponding Author’s Email Address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Although Nigeria is the largest producer and exporter of ginger in Studies were conducted in the wet season of 2018 to evaluate the Africa (FAO, 2008), the level of production is generally low performance of three ginger cultivars in five Local Government compared to other export crops. The yield is low but of high Areas of Kaduna State, Nigeria. The treatments consisted of three quality that has high demand in the world market. 80% of cultivars of ginger (UG1, UG2 and “China”) planted in five locations Nigeria’s ginger comes from the southern part of Kaduna State (Kafanchan in Jema’a LGA, Kagoro in Kaura LGA, Samaru in where, according to Momber (1942), it has been in production Zangon Kataf LGA, Kubatcha in Kagarko LGA and Kwoi in Jaba since 1927. Several farms in Southern Kaduna could only LGA).The results showed significant effects of location and produce about 2–5 t/ha and the average yield of ginger under cultivar on some of the parameters evaluated. The “China” farmer management conditions in Nigeria is reported to be about cultivar at Kafanchan, Kubatcha and Kwoi as well as UG1 at 2.5 - 5 t/ha which is far short of yield currently obtained in most Kubatcha produced statistically similar yields of ginger by dry parts of the world. -

NIGERIA | Attacks Kill 22

7.13.2020 NIGERIA | Attacks Kill 22 At least 22 people were killed and an unknown number injured and displaced in a series of attacks between July 10 and 12 by armed assailants of Fulani ethnicity on remote communities in southern Kaduna state. The attacks occurred despite a substantial security presence in the area and a 24-hour curfew that has been in place since the murder of a church leader’s son on June 10. On July 10, nine people were killed and many more were injured during an attack on the Chibwob community in Gora Ward, Zangon Kataf Local Government Area (LGA) in the Atyap Chiefdom, which occurred at 1.30 a.m. Most of the victims were women and children. The assailants also burned down over 20 homes, several motorcycles, and a car. They destroyed farms, stole livestock, and looted property and food stocks. On July 11, armed Fulani assailants attacked several settlements close to Chibwob, including the Kigudu community on the boundary between Zangon Kataf and Kauru LGAs, where 10 women, one infant and an elderly man were burned to death inside a house in which they had taken refuge. On July 12, the militia launched a morning attack on Ungwan Audu village in the Gora Ward of Zangon Kataf LGA, killing one person and looting the entire village before burning it down entirely. The weekend’s violence displaced 163 households, consisting of 1,013 people and including 11 pregnant women. They are currently sheltering in an emergency camp at an Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA) educational facility in Zangon Kataf LGA. -

Lexicalization of Property Concepts: Evidence for Language Contact on the Southern Jos Plateau (Central Nigeria)?

Lexicalization of property concepts: Evidence for language contact on the southern Jos Plateau (Central Nigeria)? Birgit Hellwig Abstract This paper discusses issues of language contact within the Jos Plateau sprach- bund of Central Nigeria. It is known that the non-related Chadic and Benue- Congo languages of this region share numerous lexical and structural simi- larities, but it is largely unknown whether they also share similarities in their semantics and lexicalization patterns. This paper explores convergences in one such area: the lexicalization of property — or adjectival — concepts in the Chadic (Angas-Goemai and Ron groups) and Benue-Congo (Jukunoid, Tarok and Fyem) languages of the southern part of this sprachbund. It presents evi- dence that these non-related languages share a common lexicalization pattern: the predominant coding of property concepts in state-change verbs. This pat- tern is probably not of Chadic origin, and it is possible that it has entered the Chadic languages of the Jos Plateau through language contact. 1. Introduction The Jos Plateau region of Central Nigeria constitutes a linguistic area or sprachbund. Language contact has shaped the non-related Chadic and Benue- Congo languages of this region to the extent that they now share numerous similarities in their lexical forms, phonotactics, (frozen) morphology, and syn- tactic patterns. It is an empirical question as to whether they also share seman- tic structures and lexicalization patterns. This paper traces convergences in one such area: the lexicalization -

An Atlas of Nigerian Languages

AN ATLAS OF NIGERIAN LANGUAGES 3rd. Edition Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road, Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone 00-44-(0)1223-560687 Mobile 00-44-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Skype 2.0 identity: roger blench i Introduction The present electronic is a fully revised and amended edition of ‘An Index of Nigerian Languages’ by David Crozier and Roger Blench (1992), which replaced Keir Hansford, John Bendor-Samuel and Ron Stanford (1976), a pioneering attempt to synthesize what was known at the time about the languages of Nigeria and their classification. Definition of a Language The preparation of a listing of Nigerian languages inevitably begs the question of the definition of a language. The terms 'language' and 'dialect' have rather different meanings in informal speech from the more rigorous definitions that must be attempted by linguists. Dialect, in particular, is a somewhat pejorative term suggesting it is merely a local variant of a 'central' language. In linguistic terms, however, dialect is merely a regional, social or occupational variant of another speech-form. There is no presupposition about its importance or otherwise. Because of these problems, the more neutral term 'lect' is coming into increasing use to describe any type of distinctive speech-form. However, the Index inevitably must have head entries and this involves selecting some terms from the thousands of names recorded and using them to cover a particular linguistic nucleus. In general, the choice of a particular lect name as a head-entry should ideally be made solely on linguistic grounds. -

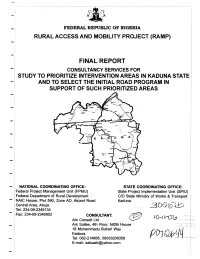

Final Report

-, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA RURAL ACCESS AND MOBILITY PROJECT (RAMP) FINAL REPORT CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR STUDY TO PRIORITIZE INTERVENTION AREAS IN KADUNA STATE - 1AND TO SELECT THE INITIAL ROAD PROGRAM IN SUPPORT OF SUCH PRIORITIZED AREAS STATE COORDINATING OFFICE: - NATIONAL COORDINATING OFFICE: Federal Project Management Unit (FPMU) State Project Implementation Unit (SPIU) 'Federal Department of Rural Development C/O State Ministry of Works & Transport Kaduna. - NAIC House, Plot 590, Zone AO, Airport Road Central Area, Abuja. 3O Q5 L Tel: 234-09-2349134 Fax: 234-09-2340802 CONSULTANT:. -~L Ark Consult Ltd Ark Suites, 4th Floor, NIDB House 18 Muhammadu Buhari Way Kaduna.p +Q q Tel: 062-2 14868, 08033206358 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction 1 Scope and Procedures of the Study 1 Deliverables of the Study 1 Methodology 2 Outcome of the Study 2 Conclusion 5 CHAPTER 1: PREAMBLE 1.0 Introduction 6 1.1 About Ark Consult 6 1.2 The Rural Access and Mobility Project (RAMP) 7 1.3 Terms of Reference 10 1.3.1 Scope of Consultancy Services 10 1.3.2 Criteria for Prioritization of Intervention Areas 13 1.4 About the Report 13 CHAPTER 2: KADUNA STATE 2.0 Brief About Kaduna State 15 2.1 The Kaduna State Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy 34 (KADSEEDS) 2.1.1 Roads Development 35 2.1.2 Rural and Community Development 36 2.1.3 Administrative Structure for Roads Development & Maintenance 36 CHAPTER 3: IDENTIFICATION & PRIORITIZATION OF INTERVENTION AREAS 3.0 Introduction 40 3.1 Approach to Studies 40 -

List of Community Banks Converted to Microfinance Banks As at 31St

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA IMPORTANT NOTICE LIST OF COMMUNITY BANKS THAT HAVE SUCESSFULLY CONVERTED TO MICROFINANCE BANKS AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2007 Following the expiration of December 31, 2007 deadline for all existing community banks to re-capitalize to a minimum of N20 million shareholders’ fund, unimpaired by losses, and consequently convert to microfinance banks (MFB), it is imperative to publish the outcome of the conversion exercise for the guidance of the general public. Accordingly, the attached list represents 607 erstwhile community banks that have successfully converted to microfinance banks with either final licence or provisional approval. This list does not, however, include new investors that have been granted Final Licences or Approvals-In- Principle to operate as microfinance banks since the launch of Microfinance Policy on December 15, 2005. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) hereby states categorically that only the community banks on this list that have successfully converted to microfinance banks shall continue to be supervised by the CBN. Members of the public are hereby advised not to transact business with any community bank which is not on the list of these successfully converted microfinance banks. Any member of the public, who transacts business with any community bank that failed to convert to MFB does so at his/her own risk. Members of the public are also to note that the operating licences of community banks that failed to re-capitalize and consequently do not appear on this list, have automatically been revoked pursuant to Section 12 of BOFIA, 1991 (as amended). For the avoidance of the doubt, new applications either as a Unit or State Microfinance Banks from potential investors or promoters shall continue to be received and processed for licensing by the Central Bank of Nigeria. -

Southern Kaduna: Democracy and the Struggle for Identity and Independence by Non-Muslim Communities in Northern Nigeria 1999- 2011

Presented at the 34th AFSAAP Conference Flinders University 2011 M. D. Suleiman, History Department, Bayero University, Kano Southern Kaduna: Democracy and the struggle for identity and Independence by Non-Muslim Communities in Northern Nigeria 1999- 2011 ABSTRACT Many non- Muslim communities were compelled to live under Muslim administration in both the pre-colonial, colonial and post colonial era in Nigeria While colonialism brought with it Christianity and western education, both of which were employed by the non-Muslims in their struggle for a new identity and independence, the exigencies of colonial administration and post- independence struggle made it difficult for non-Muslim communities to fully assert their independence. However, Nigeria’s new democratic dispensation ( i.e. Nigeria’s third republic 1999-to 2011 ) provided great opportunities and marked a turning point in the fortune of Southern Kaduna: first, in his 2003-2007 tenure, Governor Makarfi created chiefdoms ( in Southern Kaduna) which are fully controlled by the non-Muslim communities themselves as a means of guaranteeing political independence and strengthening of social-political identity of the non-Muslim communities, and secondly, the death of President ‘Yar’adua led to the emergence and subsequent election of Governor Patrick Ibrahim Yakowa in April 2011 as the first non-Muslim civilian Governor of Kaduna State. How has democracy brought a radical change in the power equation of Kaduna state in 2011? INTRODUCTION In 1914, heterogeneous and culturally diverse people and regions were amalgamated and brought together into one nation known as Nigeria by the British colonial power. In the next three years or so therefore, i.e., in 2014, the Nigerian nation will be one hundred years old. -

Kafachan Peace Declaration, the Southern Kaduna State Inter

PREAMBLE We, the parties to this Declaration are: development/cultural associations, Traditional Councils, youth, women, religious and respected opinion leaders and elders brought together by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD), with our consent, because of our history of Inter-communal, farmer and grazer and religious violence. Southern Kaduna has had a number of experiences of violent conflict that constitute a major threat to peace and security. Electoral disputes, farmer and grazer differences in particular, have caused violence, deaths, injuries, loss of property, trauma, widows and orphans, poverty and massive displacements. The stakeholders in this Declaration are convinced that a necessary condition for establishing lasting peace in our State is the resort to dialogue to resolve conflicts. This Declaration covers content from a multi- ethnic and farmer and grazer context of communities of five Local Government Areas (LGA’s) of Southern Kaduna; Sanga, Kachia, Kaura, Zangon Kataf and Jema’a. This Declaration records agreements arrived at as a first step towards achieving lasting peace. The Southern Kaduna State Inter-Communal Dialogue: Convinced that without peace, Kaduna State, cannot consolidate unity and promote democracy and development; Convinced that dialogue and the non-resort to violence can lead to a lasting solution for Kaduna State’s Inter-communal conflicts; Reaffirms that respect for human rights is indispensable for the maintenance of peace and security in Kaduna State and that it constitutes one of the fundamental blocks for sustainable development; Further reaffirms the principles enshrined in the 1999 Nigeria constitution as amended, in particular Chapter 4, section 33, subsection 1, which says “each person has a right to life, and no one shall be deprived intentionally of his life, save in execution of the sentence of the court in respect of a criminal offence of which he has been found guilty in Nigeria”. -

The Kafanchan Peace Declaration

THE KAFANCHAN PEACE DECLARATION March 23rd, 2016 Kafanchan, Kaduna State, Nigeria 1 CONTENTS The Kafanchan Peace Declaration I. Purpose II. Acknowledgement of causes and consequences of violence III. Acknowledgement of previous efforts to find a solution to the violence IV. Code of conduct V. Follow up actions VI. Dispute resolution VII. Requests to other processes and institutions The farmers and grazers Declaration VIII. Commitments and claims of grazers IX. Commitments and claims of farmers X. Policy recommendations for State Government of Kaduna and Federal Government of Nigeria XI. Recommendations for the international community, civil society and other stakeholders working in Kaduna State XII. Establishment of a monitoring committee XIII. Shared stipulations XIV. Review of this declaration XV. Walking forward together XVI. Public apology 2 PREAMBLE We, the parties to this Declaration are: development/cultural associations, Traditional Councils, youth, women, religious and respected opinion leaders and elders brought together by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD), with our consent, because of our history of Inter-communal, farmer and grazer and religious violence. Southern Kaduna has had a number of experiences of violent conflict that constitute a major threat to peace and security. Electoral disputes, farmer and grazer differences in particular, have caused violence, deaths, injuries, loss of property, trauma, widows and orphans, poverty and massive displacements. The stakeholders in this Declaration are convinced that a necessary condition for establishing lasting peace in our State is the resort to dialogue to resolve conflicts. This Declaration covers content from a multi- ethnic and farmer and grazer context of communities of five Local Government Areas (LGA’s) of Southern Kaduna; Sanga, Kachia, Kaura, Zangon Kataf and Jema’a. -

Reconstructing Benue-Congo Person Marking II

Kirill Babaev Russian State University for the Humanities Reconstructing Benue-Congo person marking II This paper is the second and last part of a comparative analysis of person marking systems in Benue-Congo (BC) languages, started in (Babaev 2008, available online for reference). The first part of the paper containing sections 1–2 gave an overview of the linguistic studies on the issue to date and presented a tentative reconstruction of person marking in the Proto- Bantoid language. In the second part of the paper, this work is continued by collecting data from all the other branches of BC and making the first step towards a reconstruction of the Proto-BC system of person marking. Keywords: Niger-Congo, Benue-Congo, personal pronouns, comparative research, recon- struction, person marking. The comparative outlook of person marking systems in the language families lying to the west of the Bantoid-speaking area is a challenge. These language stocks (the East BC families of Cross River, Plateau, Kainji and Jukunoid, and the West BC including Edoid, Nupoid, Defoid, Idomoid, Igboid and a few genetically isolated languages of Nigeria) are still far from being sufficiently studied or even described, and the amount of linguistic data for many of them re- mains quite scarce. In comparison with the Bantu family which has enjoyed much attention from comparative linguists within the last decades, there are very few papers researching the other subfamilies of BC from a comparative standpoint. This is especially true for studies in morphology, including person marking. The aim here is therefore to make the very first step towards the comparative analysis and reconstruction of person markers in BC. -

In Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria

HUMAN “Leave Everything to God” RIGHTS Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence WATCH in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria “Leave Everything to God” Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0855 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0855 “Leave Everything to God” Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria Summary and Recommendations ....................................................................................................