PAI O on the Connexion of Vegetation Dynamics with Climatic Changes In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest

2019 Status Report Palampur Palampur Forest Division Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest Division of Dharamshala Forest Circle, Himachal Pradesh Harish Bharti, Aditi Panatu, Kiran and Dr. S. S. Randhawa H. P. State Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan near Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe Shimla-01 0177-2656489 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Forests of Himachal Pradesh........................................................................................................................ 5 Study area and method ....................................................................................................................... 7 District Kangra A Background .................................................................................................................. 7 Location & Geographical– Area ................................................................................................................. 8 Palampur Forest Division- Forest Profile................................................................................................ 9 Name and Situation:- .................................................................................................................................. 9 Geology: ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 -

Burlington House

Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Contents Pages 2-5 Oral Programme Pages 6-7 Poster programme Pages 8-33 Oral presentation abstracts (in programme order) Pages 34-63 Poster presentations abstracts (in programme order) Pages 64-65 Conference sponsor information Pages 65-68 Notes 24-26 June 2014 Page 1 Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Oral Programme Tuesday 24 June 2014 09.00 Welcome 11.30 Student presentation from Leh School 11.45 A life in Ladakh Professor (ambassador) Phunchok Stobdan, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses 12.30 Lunch and posters 14.00 Mountaineering in the Himalaya Ang Rita Sherpa, Mountain Institute, Kathmandu, Nepal Session theme: The geological framework of the Himalaya 14.30 Geochemical and isotopic constraints on magmatic rocks – some constraints on collision based on new SHRIMP data Professor Talat Ahmed, University of Kashmir 15.15 Short subject presentations and panel discussion Moderators: Director, Geology & Mining, Jammu & Kashmir State & Director, Geological Survey of India Structural framework of the Himalayas with emphasis on balanced cross sections Professor Dilip Mukhopadhyay, IIT Roorkee Sedimentology Professor S. K. Tandon, Delhi University Petrogenesis and economic potential of the Early Permian Panjal Traps, Kashmir, India Mr Greg Shellnut, National Taiwan Normal University Precambrian Professor D. M. Banerjee, Delhi University 16.00 Tea and posters 16.40 Short subject presentations continued & panel discussion 18.00 Close of day 24-26 June 2014 Page 2 Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Wednesday 25 June 2014 Session theme: Climate, Landscape Evolution & Environment 09.00 Climate Professor Harjeet Singh, JNU, New Delhi 09.30 Earth surface processes and landscape evolution in the Himalaya Professor Lewis Owen, Cincinnati University 10.00 Landscape & Vegetation Dr P. -

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Solan Forest Division of Nahan Circle, Himachal Pradesh Status Report

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Solan Forest Division of Nahan Circle, Himachal Pradesh Status Report 02-Sep-19 Himachal Pradesh Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan Bemloe, Shimla-01 H.P. India Harish Bharti, KIran Lata and Aditi Panatu and Dr. S.S. Randhawa Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Forests of Himachal Pradesh .............................................................................................................. 4 Study area and method ............................................................................................................................ 6 District Solan – A Background ............................................................................................................ 6 Methods ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Solan Forest Division – ............................................................................................................................. 9 Assessment techniques .......................................................................................................................... 11 Tree Community-based Variations .................................................................................................. 11 Results & Findings ............................................................................................................................ -

2019 Fall Order Form UNITED STATES

2019 Fall Order Form UNITED STATES Expires: October 23, 2019 BILLING AND SHIPPING INFORMATION - A street address is required for delivery. Membership Number: _____________________________ E-mail address: _________________________________ Daytime Phone: __ __ __ - __ __ __ - __ __ __ - __ __ __ __ Fax Number: __ __ __ - __ __ __ - __ __ __ __ Country code + area code required Country code + area code required BILLING ADDRESS: _____ Residential _____ Business SHIP TO: (if different) _____Residential or _____Business Name:____________________________________________ Name:___________________________________________ Address:__________________________________________ Address:__________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ INSTRUCTIONS: Please read carefully and fill out this form completely. Incomplete or illegible orders cannot be processed. We suggest you mark your calendar and make a copy of this order form for your records. If you would like to pick up your plants at the RSBG, please mark below: _____ I will PICK UP my plants at the Garden office on Saturday, October 19, 2019. Pickup will be from 9am to 12 noon only. PLANT SHIPMENT: ALL shipments will be via UPS Ground Service unless otherwise instructed. CHECK YOUR PREFERENCE: _____ UPS Ground (Do not use if shipping east of the Mississippi) _____ UPS 3 Day Select _____ UPS 2nd Day Air _____ Monday, September 23 _____ Monday, September 30 _____ Monday, October 14 _____ Monday, October 28 Shipping and Handling Rates PAYMENT INFORMATION This chart is for cost estimation only. UPS frequently adds surcharges for fuel cost and delivery area. Actual shipping costs will be adjusted on your final invoice. As a service to RSBG Members, prepayment is not required. Zones # of Plants A B C ____ Bill me with plant shipment, or fill in credit card information below. -

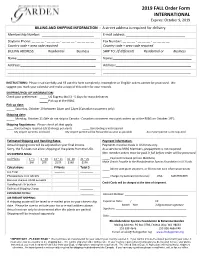

2019 FALL Order Form INTERNATIONAL

2019 FALL Order Form INTERNATIONAL Expires: October 9, 2019 BILLING AND SHIPPING INFORMATION - A street address is required for delivery. Membership Number: _____________________________ E-mail address: _________________________________ Daytime Phone: __ __ __ - __ __ __ - __ __ __ - __ __ __ __ Fax Number: __ __ __ - __ __ __ - __ __ __ __ Country code + area code required Country code + area code required BILLING ADDRESS: _____ Residential _____ Business SHIP TO: (if different) _____Residential or _____Business Name:____________________________________________ Name:____________________________________________ Address:__________________________________________ Address:__________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ INSTRUCTIONS: Please read carefully and fill out this form completely. Incomplete or illegible orders cannot be processed. We suggest you mark your calendar and make a copy of this order for your records. SHIPPING/PICK-UP INFORMATION: Check your preference: _____ US Express Mail 3 - 5 days for most deliveries _____ Pick up at the RSBG Pick up date: _____ Saturday, October 19 between 10am and 12pm (Canadian customers only) Shipping date: _____ Monday, October 21 (We do not ship to Canada - Canadian customers must pick orders up at the RSBG on October 19th) Shipping Regulations: Please check all that apply. _____ Barerooting is required (US $5 charge per plant) _____ Barerooting is not required _____ My import permit is enclosed _____ My import permit will be forwarded as soon as possible _____ An import permit is not required Estimated Shipping and Handling Rates: Payment Information: Actual shipping costs will be adjusted on your final invoice. Payments must be made in US funds only. Sorry, the EU does not allow shipping of live plants from the USA. -

Step-Two Lectotypification and Epitypification of Pentapterygium Sikkimense W.W

Panda, S. and J.L. Reveal. 2012. A step-two lectotypification and epitypification of Pentapterygium sikkimense W.W. Sm. (Ericaceae) with an amplified description. Phytoneuron 2012-8: 1–7. Published 1 February 2012. ISSN 2153 733X A STEP-TWO LECTOTYPIFICATION AND EPITYPIFICATION OF PENTAPTERYGIUM SIKKIMENSE W.W. SM. (ERICACEAE) WITH AN AMPLIFIED DESCRIPTION SUBHASIS PANDA Taxonomy & Biosystematics Laboratory Post-Graduate Department of Botany Darjeeling Government College P.O. North Point Darjeeling-734101, India e-mail: [email protected] JAMES L. REVEAL L.H. Bailey Hortorium Department of Plant Biology 412 Mann Library Building Cornell University Ithaca, New York 14853-4301 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT An epitype is selected for Pentapterygium sikkimense W.W. Sm., the basionym of Agapetes smithiana Sleumer, to augment the inadvertent lectotypification by Airy Shaw (1959) on a G.A. Gammie collection from Sikkim, India. A step-two lectotypfication on the specimen at Kew is designated here. An amplified description of var. smithiana is provided. Photographs of the lectotype, isolectotype, epitype, and live plants are provided to facilitate identification. KEY WORDS: typification, Sikkim, West Bengal, India. Pentapterygium sikkimense was described by William Wright Smith (1911 268) based on specimens collected by George Alexander Gammie in 1892 ( 1216 , K! [Fig. 1], CAL! [Fig. 2]) from Lachung Valley in the state of Sikkim, and by Charles Gilbert Rogers in 1899 (accession no. 264374, CAL!) from the lower Tonglu region of the Darjeeling Himalaya in the state of West Bengal, India. Sleumer (1939: 106) transferred P. sikkimense to Agapetes D. Don ex G. Don and proposed a new named, A. -

Management Plan 2006 - 2010

PHOBJIKHA LANDSCAPE CONSERVATION AREA Management Plan 2006 - 2010 The Royal Society for Protection of Nature The Royal Society for Protection of Nature Post Box 325 Thimphu, BHUTAN All Rights Reserved © 2005 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Royal Society for Protection of Nature (RSPN), the only non-governmental conservation organization in Bhutan, has been a key player in the conservation of the endangered Black-necked Cranes in Phobjikha valley. The survival of the Black – necked Cranes in Phobjikha, is linked with the humans. As residents of Phobjikha move down to the lower elevations of Ada to escape severe winter, their migration has safeguarded wintering cranes and their habitat in Phobjikha. Therefore, contributions to crane conservation from Ada as winter homes for several hundred households and their wetland farms, are of enormous values. To know more about Phobjikha valley, RSPN had completed two studies with vital information on how human experiences have shaped their natural surroundings including the survival of the Black-necked Cranes. Based on the occurrence of endangered species such as the Black-necked Cranes, White-bellied Heron, red panda and tigers, the preliminary boundary of the Phobjikha Landscape Conservation Area (PLCA) was delineated to include both Phobjikha and Ada. The boundary falls within 890 57’ 54” - 900 17’ 30” North and 270 13’ 50” - 270 31’ 27 East, with an area of 402.9 km2. Within the PLCA boundary, the Phobjikha valley (rim) was considered the crane area (161.9 km2 ; 900 5’ 55” – 900 17’ 30” North and 270 22’ 16” – 270 31’ 27” East). Seven major land-use were identified: agriculture, forest, scrub, marsh, water-bodies, pastures and settlements. -

U Niversity of Graz Samentauschverzeichnis

Instutute of Plant Sciences –University of Graz Pflanzenwissenschaften Institut für Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Samentauschverzeichnis Botanischer Garten - Seminum Index - 2015 SAMENTAUSCHVERZEICHNIS Index Seminum Seed list Catalogue de graines des Botanischen Gartens der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Ernte / Harvest / Récolte 2015 Herausgegeben von Christian BERG & Kurt MARQUART ebgconsortiumindexseminum2012 Institut für Pflanzenwissenschaften, Januar 2016 Botanical Garden, Institute of Plant Sciences, Karl- Franzens-Universität Graz 2 Botanischer Garten Institut für Pflanzenwissenschaften Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Holteigasse 6 A - 8010 Graz, Austria Fax: ++43-316-380-9883 Email- und Telefonkontakt: [email protected], Tel.: ++43-316-380-5651 [email protected], Tel.: ++43-316-380-5747 Webseite: http://garten.uni-graz.at/ Zitiervorschlag : BERG, C. & MARQUART, K. (2015): Samentauschverzeichnis – Index Seminum - des Botanischen Gartens der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Samenernte 2015. – 58 S., Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. Personalstand des Botanischen Gartens Graz: Institutsleiter: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Helmut MAYRHOFER Wissenschaftlicher Gartenleiter: Dr. Christian BERG Gartenverwalter: Jonathan WILFLING, B. Sc. Gärtnermeister: Friedrich STEFFAN GärtnerInnen: Doris ADAM-LACKNER Viola BONGERS Magarete HIDEN Franz HÖDL Kurt MARQUART Franz STIEBER Ulrike STRAUSSBERGER Gartenarbeiter: Herbert GRÜBLER / Philip FRIEDL René MICHALSKI Alfred PROBST / Oliver KROPIWNICKI Gärtnerlehrlinge: Bahram EMAMI (1. Lehrjahr) -

Social Impact Investment in Tourism Sustainable Tourism October15, 2014 UNWTO Themis Foundation George Washington University

Social Impact Investment in Tourism Sustainable Tourism October15, 2014 UNWTO Themis Foundation George Washington University Mary Andrade CFO/Operations www.ashoka.org Leadership Group Member of Ashoka 1 Table of Content Social Entrapreneurs Slide • Ashoka - about us 3 • Ashoka fellow wins Nobel Peace 4 Prize; Kailash Satyarthi – South Asia • What are Social Entrepreneurs 5 • Sustainable tourism – MEGH ALE- Nepal 6 - 12 – JADWIGA LOPATA – Poland – MANOJ BHATT – India – MARIA BARYAMUJURA – Uganda – SEBASTIáN GATICA – Chile – CECILIA ZANOTTI – Brazil 13 – 15 • Conclusion 16 - 29 • Appendix 2 About Us Ashoka envisions an Everyone A Changemaker™ world: one that responds quickly and effectively to social challenges, and where each individual has the freedom, confidence and societal support to address any social problem and drive change. 3 Ashoka fellow wins Nobel Peace Prize - 2014 Kailash Satyarthi, who was elected as an Ashoka fellow in 1993 for his work on child rights, has won this year’s Nobel Peace prize Kailash founded the grassroots movement Bachpan Bachao Andolan - Save the Childhood Movement and Rugmark - a rug trademarking organization that guaranteed fair practices and no child labor. These movements have rescued over 80,000 children from the scourge of bondage, trafficking and exploitative labour in the last three decades. Kailash Satyarthi is a renowned leader in the global movement against child labor. Today, in addition to his trademark organization Rugmark, Kailash heads the Global March Against Child Labor, a conglomeration -

Managing Public Lands in a Subsistence Economy: the Perspective from a Nepali Village

MANAGING PUBLIC LANDS IN A SUBSISTENCE ECONOMY: THE PERSPECTIVE FROM A NEPALI VILLAGE by JEFFERSON METZ FOX A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Development) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN—MADISON 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page THE PROBLEM, THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK, 1 AND OBJECTIVES A. The Problem B. Theoretical Framework A Brief History of Public Lands in Nepal Local Participation and Land Use Management 8 Constraints on Local Participation 11 Competition for Land 11 Present Needs 12 Distribution of Benefits 13 Labor Requirements 14 C. Objectives 15 D. Outline of this Thesis 17 II THE SETTING, METHODS, AND DEFINITONS 19 A. Setting 19 The Middle-Hills 19 The Daraundi Watershed 20 22 The Village Physical Features of the Village 24 Cultural Features of the Village 28 A Short Walk Through the Village 31 iv B. Methods • 35 The Physical Environment 35 Land Use and Land Area 35 Forest Inventory 37 Demands for Forest Products 37 Sample Population 37 Daily Recall Survey 38 Time Allocation Survey 38 Weight Survey 39 Census Survey 39 Assistants 40 C. Definitions • 40 Farm-Size 41 Forest-Type 42 III FIREWOOD 45 A. Introduction 45 B. Forest Resources 46 C. Firewood Collecting Patterns 56 D. Firewood Collecting Labor Patterns 62 E. Firewood Demand and Consumption Patterns 68 Firewood Consumption Rates 69 Factors Affecting Firewood Consumption Rates 71 Family Size 72 Caste 73 Farm Size 74 Season 76 F. Village Firewood Requirements 80 G. Firewood Supplies versus Firewood Demands 80 H. Conclusions 83 V IV FODDER AND GRAZING 86 A. -

Holy Cross Fax: Worcester, MA 01610-2395 UNITED STATES

NEH Application Cover Sheet Summer Seminars and Institutes PROJECT DIRECTOR Mr. Todd Thornton Lewis E-mail:[email protected] Professor of World Religions Phone(W): 508-793-3436 Box 139-A 425 Smith Hall Phone(H): College of the Holy Cross Fax: Worcester, MA 01610-2395 UNITED STATES Field of Expertise: Religion: Nonwestern Religion INSTITUTION College of the Holy Cross Worcester, MA UNITED STATES APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Literatures, Religions, and Arts of the Himalayan Region Grant Period: From 10/2014 to 12/2015 Field of Project: Religion: Nonwestern Religion Description of Project: The Institute will be centered on the Himalayan region (Nepal, Kashmir, Tibet) and focus on the religions and cultures there that have been especially important in Asian history. Basic Hinduism and Buddhism will be reviewed and explored as found in the region, as will shamanism, the impact of Christianity and Islam. Major cultural expressions in art history, music, and literature will be featured, especially those showing important connections between South Asian and Chinese civilizations. Emerging literatures from Tibet and Nepal will be covered by noted authors. This inter-disciplinary Institute will end with a survey of the modern ecological and political problems facing the peoples of the region. Institute workshops will survey K-12 classroom resources; all teachers will develop their own curriculum plans and learn web page design. These resources, along with scholar presentations, will be published on the web and made available for teachers worldwide. BUDGET Outright Request $199,380.00 Cost Sharing Matching Request Total Budget $199,380.00 Total NEH $199,380.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Ms. -

Samenkatalog Graz 2019 End.Pdf

SAMENTAUSCHVERZEICHNIS Index Seminum Seed list Catalogue de graines Botanischer Garten der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Ernte / Harvest / Récolte 2019 Herausgegeben von Christian BERG, Kurt MARQUART, Thomas GALIK & Jonathan WILFLING ebgconsortiumindexseminum2012 Institut für Biology, Januar 2020 Botanical Garden, Institute of Biology, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz 2 Botanischer Garten Institut für Biologie Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Holteigasse 6 A - 8010 Graz, Austria Fax: ++43-316-380-9883 Email- und Telefonkontakt: [email protected], Tel.: ++43-316-380-5651 [email protected], Tel.: ++43-316-380-5747 Webseite: http://garten.uni-graz.at/ Zitiervorschlag : BERG, C., MARQUART, K., GALIK, T. & Wilfling, J. (2020): Samentauschverzeichnis – Index Seminum – des Botanischen Gartens der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Samenernte 2019. – 44 S., Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz. Personalstand des Botanischen Gartens Graz: Institutsleiter: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Christian STURMBAUER Wissenschaftlicher Gartenleiter: Dr. Christian BERG Technischer Gartenleiter: Jonathan WILFLING, B. Sc. GärtnerInnen: Doris ADAM-LACKNER Viola BONGERS Thomas GALIK Margarete HIDEN Kurt MARQUART Franz STIEBER Ulrike STRAUSSBERGER Monika GABER René MICHALSKI Techn. MitarbeiterInnen: Oliver KROPIWNICKI Martina THALHAMMER Gärtnerlehrlinge: Sophia DAMBRICH (3. Lehrjahr) Wanja WIRTL-MÖLBACH (3. Lehrjahr) Jean KERSCHBAUMER (3. Lehrjahr) 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis / Contents / Table des matières Abkürzungen / List of abbreviations / Abréviations .................................................