Studying the Snow Leopard: Reconceptualizing Conservation Across the China–India Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest

2019 Status Report Palampur Palampur Forest Division Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest Division of Dharamshala Forest Circle, Himachal Pradesh Harish Bharti, Aditi Panatu, Kiran and Dr. S. S. Randhawa H. P. State Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan near Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe Shimla-01 0177-2656489 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Forests of Himachal Pradesh........................................................................................................................ 5 Study area and method ....................................................................................................................... 7 District Kangra A Background .................................................................................................................. 7 Location & Geographical– Area ................................................................................................................. 8 Palampur Forest Division- Forest Profile................................................................................................ 9 Name and Situation:- .................................................................................................................................. 9 Geology: ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 -

©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - Saveagorilla.Org 1847 Thomas Savage Discovers a Gorilla Skull and Recognizes It As a New Species

1847-2013 GORILLA TIMELINE ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1847 Thomas Savage discovers a gorilla skull and recognizes it as a new species. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1902 Captain Robert von Beringe from Germany was the first European to identify the Mountain Gorilla on the Sabinyo volcano. Because of him, the Mountain Gorilla is classified as Gorilla gorilla beringei. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1904 Cross River gorilla identified from discovery of skull bones. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1925 The Albert National Park established as a gorilla sanctuary, later renamed the Virunga National Park. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1933 “King Kong”, the movie, is released and the killing of gorillas for sport increases. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1956 The first ever gorilla is born in a zoo, named Colo. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1959 George Schaller, American zoologist, studied the mountain gorillas. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1967 Dian Fossey, founder of Karisoke Research Center, begins her study of gorillas. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1983 Dian Fossey releases her famous book, "Gorillas in the Mist", which was later turned into a film. Gorilla Timeline ©2013 Mountain Gorilla Conservation Fund - saveAgorilla.org 1985 Dian Fossey asks Ruth Morris Keesling to help her save the mountain gorillas and provide veterinary care. Fossey was later murdered on December 26 in her cabin at Karisoke Research Center, 248 mountain gorillas are alive and none are in captivity. -

Burlington House

Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Contents Pages 2-5 Oral Programme Pages 6-7 Poster programme Pages 8-33 Oral presentation abstracts (in programme order) Pages 34-63 Poster presentations abstracts (in programme order) Pages 64-65 Conference sponsor information Pages 65-68 Notes 24-26 June 2014 Page 1 Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Oral Programme Tuesday 24 June 2014 09.00 Welcome 11.30 Student presentation from Leh School 11.45 A life in Ladakh Professor (ambassador) Phunchok Stobdan, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses 12.30 Lunch and posters 14.00 Mountaineering in the Himalaya Ang Rita Sherpa, Mountain Institute, Kathmandu, Nepal Session theme: The geological framework of the Himalaya 14.30 Geochemical and isotopic constraints on magmatic rocks – some constraints on collision based on new SHRIMP data Professor Talat Ahmed, University of Kashmir 15.15 Short subject presentations and panel discussion Moderators: Director, Geology & Mining, Jammu & Kashmir State & Director, Geological Survey of India Structural framework of the Himalayas with emphasis on balanced cross sections Professor Dilip Mukhopadhyay, IIT Roorkee Sedimentology Professor S. K. Tandon, Delhi University Petrogenesis and economic potential of the Early Permian Panjal Traps, Kashmir, India Mr Greg Shellnut, National Taiwan Normal University Precambrian Professor D. M. Banerjee, Delhi University 16.00 Tea and posters 16.40 Short subject presentations continued & panel discussion 18.00 Close of day 24-26 June 2014 Page 2 Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Wednesday 25 June 2014 Session theme: Climate, Landscape Evolution & Environment 09.00 Climate Professor Harjeet Singh, JNU, New Delhi 09.30 Earth surface processes and landscape evolution in the Himalaya Professor Lewis Owen, Cincinnati University 10.00 Landscape & Vegetation Dr P. -

Who Knows What About Gorillas? Indigenous Knowledge, Global Justice, and Human-Gorilla Relations Volume: 5 Adam Pérou Hermans Amir, Ph.D

IK: Other Ways of Knowing Peer Reviewed Who Knows What About Gorillas? Indigenous Knowledge, Global Justice, and Human-Gorilla Relations Volume: 5 Adam Pérou Hermans Amir, Ph.D. Pg. 1-40 Communications Coordinator, Tahltan Central Government The gorillas of Africa are known around the world, but African stories of gorillas are not. Indigenous knowledge of gorillas is almost entirely absent from the global canon. The absence of African accounts reflects a history of colonial exclusion, inadequate opportunity, and epistemic injustice. Discounting indigenous knowledge limits understanding of gorillas and creates challenges for justifying gorilla conservation. To be just, conservation efforts must be endorsed by those most affected: the indigenous communities neighboring gorilla habitats. As indigenous ways of knowing are underrepresented in the very knowledge from which conservationists rationalize their efforts, adequate justification will require seeking out and amplifying African knowledge of gorillas. In engaging indigenous knowledge, outsiders must reflect on their own ways of knowing and be open to a dramatically different understanding. In the context of gorillas, this means learning other ways to know the apes and indigenous knowledge in order to inform and guide modern relationships between humans and gorillas. Keywords: Conservation, Epistemic Justice, Ethnoprimatology, Gorilla, Local Knowledge, Taboos 1.0 Introduction In the Lebialem Highlands of Southwestern Cameroon, folk stories tell of totems shared between gorillas and certain people. Totems are spiritual counterparts. Herbalists use totems to gather medicinal plants; hunting gorillas puts them in doi 10.26209/ik560158 danger. If the gorilla dies, the connected person dies as well (Etiendem 2008). In Lebialem, killing a gorilla risks killing a friend, elder, or even a chief (fon). -

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Solan Forest Division of Nahan Circle, Himachal Pradesh Status Report

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Solan Forest Division of Nahan Circle, Himachal Pradesh Status Report 02-Sep-19 Himachal Pradesh Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan Bemloe, Shimla-01 H.P. India Harish Bharti, KIran Lata and Aditi Panatu and Dr. S.S. Randhawa Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Forests of Himachal Pradesh .............................................................................................................. 4 Study area and method ............................................................................................................................ 6 District Solan – A Background ............................................................................................................ 6 Methods ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Solan Forest Division – ............................................................................................................................. 9 Assessment techniques .......................................................................................................................... 11 Tree Community-based Variations .................................................................................................. 11 Results & Findings ............................................................................................................................ -

Download Tibet Wild: a Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World PDF

Download: Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World PDF Free [138.Book] Download Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World PDF By George B. Schaller Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World you can download free book and read Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World for free here. Do you want to search free download Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Tibet Wild: A Naturalist's Journeys on the Roof of the World | #2409549 in Books | 2014-02-25 | Original language: English | PDF # 1 | 9.00 x 1.10 x 6.00l, 1.20 | File type: PDF | 384 pages | |6 of 6 people found the following review helpful.| Great book from a superstar of conservation | By Yeti |Tibet, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, western China, Nepal and restive north-east India all have one thing in common when it comes to making big news around the world: violence. That is unfortunate, but this is the area where the great Dr. Schaller has done fantastic work from surveys to helping establish new reserves for | From Booklist | *Starred * Field biologist and National Book Award–winner Schaller is a guiding light in global wildlife conservation. In this richly textured chronicle of five decades of world travels, he co As one of the world’s leading field biologists, George Schaller has spent much of his life traversing wild and isolated places in his quest to understand and conserve threatened species—from mountain gorillas in the Virunga to pandas in the Wolong and snow leopards in the Himalaya. -

Dian Fossey's Gorillas 50 Years On

Dian Fossey’s gorillas 50 years on: research, conservation, and lessons learned Stacy Rosenbaum Institute for Mind and Biology University of Chicago An Outline 1. A brief history (natural and human) 2. The mission today àProtect, educate, develop, learn 3. My role: ongoing research 4. Successes, lessons learned, and why it all matters Two gorilla species: western & eastern Uganda Democratic Republic of Congo Rwanda KARISOKE History of mountain gorillas in western science • 1901- Western science ‘discovers’ mountain gorillas • 1920s - Carl Akeley expeditions lead to Albert National Park • 1960 - George Schaller writes first scientific articles • 1967 – Dian Fossey establishes Karisoke Research Center • 2016 – 70+ scientists contributed to knowledge of behavior, ecology 1963: Dian Fossey meets renowned anthropologist Dr. Louis Leakey She encounters mountain gorillas for the first time, and persuades Leakey to hire her Karisoke Research Center 1967-ongoing… Observing behavior • Habituated groups for study • Fossey learned to observe individuals KarisokeKarisoke Research Research Center Center 1967-ongoing…1967-ongoing… Karisoke’s central objectives • Protection • Education • Community Development • Research* Protection & conservation historically Protection & conservation today Illegal activities Habitat Loss Direct poaching Disease transmission Gorilla protection & monitoring • Protection and monitoring for habituated gorilla groups • Assistance to national park authorities Democratic Republic Uganda of Congo Rwanda Education Sites of engagement: • Primary classrooms • Zoos (USA) • Social media • National University of Rwanda “Citizen science” project Community development Combating poverty = improved conservation outcomes Hospital building Toilet facilities Water tanks Treating intestinal parasites Solar generators Gorilla Research Program Key Karisoke research findings • Gorillas aren’t King Kong! • Socioecological principles • Male and female dispersal • Population census Ongoing project #1: Mountain gorilla stress physiology Stress: causes & consequences Drs. -

Remembering a Conservation Champion - the Life and Legacy of Art Ortenberg

Remembering a Conservation Champion - The Life and Legacy of Art Ortenberg The wildlife conservation world has lost a champion. On February 3rd, 2014, Art Ortenberg, the brilliant business partner behind the legendary... Read More A New York Times Op-Ed by Panthera's George Schaller: Saving More Than Just Snow Leopards On Sunday, the New York Times published an op-ed by Panthera's Vice President, Dr. George Schaller, and the Wildlife Conservation Society's... Read More A Day in Belize with Glenn Close and the Jaguars of Cockscomb - Part 1 Nestled in the Central American country of Belize, Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary exists as a sacred refuge - a home and passageway for the jaguars of Central America... Read More Lion Conservationist Shivani Bhalla Awarded 2013 Rabinowitz-Kaplan Prize for the Next Generation in Wild Cat Conservation Panthera is excited to announce that lion conservationist and PhD candidate, Shivani... Read More First Ever Photos of Wild Snow Leopards Taken in Uzbekistan In November and December of 2013, a team of rangers and biologists led by Bakhtiyor Aromov and Yelizaveta Protas, in collaboration with Panthera and WWF Central Asia Program... Read More The Silver Lining for the Lions of West Africa In a press release published last month, Panthera outlined the results of a new report confirming that lions are now Critically Endangered and face extinction across the entire region of... Read More World's Rarest Otter Photographed in Sumatra by Tiger Team Home to hundreds of mammal and bird species, the Indonesian island of Sumatra is most often renowned for its magnificent mega fauna, including the Sumatran tiger, rhino, elephant and orangutan.. -

Nomadic Skies Expeditions

NOMADIC SKIES EXPEDITIONS EXCLUSIVE ONE-OFF EXPEDITION In the Footsteps of Matthiessen’s Snow Leopard A UNIQUE LITERARY JOURNEY INTO THE LANDSCAPES, CULTURE & PEOPLE OF REMOTE NEPAL A 23-day camp trekking expedition into remote and hidden Dolpo in North West Nepal to the monastery of the sacred Crystal Mountain. Peter Matthiessen’s book, The Snow Leopard, was first published in 1978 and has since became a classic piece of travel literature, winning the National Book Award twice. The book charts the author’s journey to the sacred Crystal Mountain in remote High Himalayan NW Nepal with field naturalist George Schaller. Matthiessen was seeking the illusive snow leopard but also undertaking a spiritual journey, while George Schaller was aiming to complete field research into the Mountain Bharal (blue sheep) of the high Himalaya. The publication of The Snow Leopard was the first major book to bring the remote Dolpo area into international focus. Not long after Matthiessen and Schaller visited, the area was closed to visitors for decades, and though it is now open again, the area remains little visited and remote, retaining its vibrant Tibetan culture. Photos - original archive from the 1973 expedition, courtesy of George Schaller. TRUE NATURE: THE ODYSSEY OF PETER MATTHIESSEN Asked to define himself, Peter Matthiessen liked to say, simply, that he was “a fiction writer.” But he was also a journalist and naturalist, an ornithologist and ichthyologist, a fisherman, explorer, and labor rights activist — not to mention a fleeing CIA agent who co-founded the Paris Review as his cover. As a seeker, restlessly searching, Matthiessen was attuned to both science and mysticism, which made him, in the words of one admirer, “a kind of Thoreau-on-the-Road.” At the start of the 1970s, he traded psychedelics for Zen Buddhism; he eventually attained the rank of Zen roshi. -

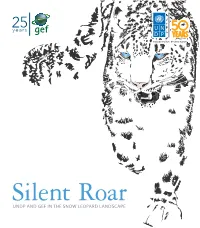

Silent Roar | UNDP and GEF in the Snow Leopard Landscape

25years Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Silent Roar UNDP AND GEF IN THE SNOW LEOPARD LANDSCAPE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS Managing Editors: Midori Paxton, Tim Scott, Yoko Watanabe Compilation and Editing: Erin Charles INTRODUCTION 2 CO-MANAGEMENT ON THE ROOF 21 CONCLUSION 44 OF THE WORLD—CHINA Core Writing Team: Erin Charles, Midori Paxton, Tim Scott, Doley Tshering, Inela Weeks SNOW LEOPARD RANGE MAP 4 PARTNER SPOTLIGHT: 23 We wish to acknowledge the UNDP and GEF staff, consultants, and partners who contributed to this publication: GOVERNMENTS AND GOVERNANCE Tehmina Akhtar, Ana Maria Currea, Adriana Dinu, Lisa Farroway, Gustavo Fonseca, Uyanga Gankhuyag, Christian LESSONS LEARNED: RUSSIA, 23 ART AND CULTURE Hofer, Daniar Ibragimov, Kyle Kaufman, Khurshed Kholov, Fan Longqing, Cathy Maize, Ruchi Pant, Pakamon MONGOLIA, AND KAZAKHSTAN Pinprayoon, Evgeniia Postnova, Ajiniyaz Reimov, Olga Romanova, Nadisha Sidhu, Nargizakhon Usmanova, SNOW LEOPARDS IN LITERATURE 19 SECTION 1: WHY SNOW LEOPARDS? 6 STRENGTHENING AND EXPANDING 24 Maxim Vergeichik, Katerina Yushenko, Yuqiong Zhou, with special thanks to Marc Foggin and John MacKinnon WHY PROTECT THE HIGH 8 PROTECTED AREAS—KAZAKHSTAN SNOW LEOPARDS AND 21 for generously permitting the extensive use of their photographs. TIBETAN BUDDHISM MOUNTAIN LANDSCAPES? PARTNER SPOTLIGHT: TRAINING 25 We wish to acknowledge the central role of the GSLEP Secretariat: Hamid Zahid (Chair), Abdykalyk Rustamov CULTURAL-POLITICAL SYMBOLS 37 UNIQUE BIODIVERSITY 8 OF TRAINERS (Co-chair), Kyial Alygulova, Yash Veer Bhatnagar, Chyngyz Kochorov, Andrey Kushlin, Keshav Varma, with special LAND USE PLANNING & BIOLOGICAL 26 SACRED BELIEFS, MYTHS 40 ASIA'S WATER TOWER 9 thanks to Koustubh Sharma and Matthias Fiechter for their technical review of this document, contributions CORRIDORS— KYRGYZSTAN AND LEGENDS of text, photographs, maps and invaluable feedback on all aspects of the publication; and the Permanent CULTURAL HERITAGE 9 LESSONS LEARNED: BHUTAN 27 Mission of the Kyrgyz Republic to the UN in New York: Madina Karabaeva. -

Social Impact Investment in Tourism Sustainable Tourism October15, 2014 UNWTO Themis Foundation George Washington University

Social Impact Investment in Tourism Sustainable Tourism October15, 2014 UNWTO Themis Foundation George Washington University Mary Andrade CFO/Operations www.ashoka.org Leadership Group Member of Ashoka 1 Table of Content Social Entrapreneurs Slide • Ashoka - about us 3 • Ashoka fellow wins Nobel Peace 4 Prize; Kailash Satyarthi – South Asia • What are Social Entrepreneurs 5 • Sustainable tourism – MEGH ALE- Nepal 6 - 12 – JADWIGA LOPATA – Poland – MANOJ BHATT – India – MARIA BARYAMUJURA – Uganda – SEBASTIáN GATICA – Chile – CECILIA ZANOTTI – Brazil 13 – 15 • Conclusion 16 - 29 • Appendix 2 About Us Ashoka envisions an Everyone A Changemaker™ world: one that responds quickly and effectively to social challenges, and where each individual has the freedom, confidence and societal support to address any social problem and drive change. 3 Ashoka fellow wins Nobel Peace Prize - 2014 Kailash Satyarthi, who was elected as an Ashoka fellow in 1993 for his work on child rights, has won this year’s Nobel Peace prize Kailash founded the grassroots movement Bachpan Bachao Andolan - Save the Childhood Movement and Rugmark - a rug trademarking organization that guaranteed fair practices and no child labor. These movements have rescued over 80,000 children from the scourge of bondage, trafficking and exploitative labour in the last three decades. Kailash Satyarthi is a renowned leader in the global movement against child labor. Today, in addition to his trademark organization Rugmark, Kailash heads the Global March Against Child Labor, a conglomeration -

HIMALAYAN KINGDOMS Ere Is a Brief Selection of Favorite, New and Hard-To-Find Books, Prepared for Your Journey

READING GUIDE HIMALAYAN KINGDOMS ere is a brief selection of favorite, new and hard-to-find books, prepared for your journey. For your convenience, you may call (800) 342-2164 to order these books directly from Longitude, a specialty mail- Horder book service. To order online, and to get the latest, most comprehensive selection of books for your voyage, go directly to reading.longitudebooks.com/D923075. Nelles ESSENTIAL Himalaya Map 2011, MAP, PAGES, $13.95 Item EXHML82. Buy these 5 items as a set for $109 A colorful regional map of the Himalayas at a including shipping, 15% off the retail price. With free scale of 1:1,500,000, including Nepal, Bhutan, shipping on anything else you order. Tibet and Sikkim. (Item HML09) Barbara Crossette So Close to Heaven, The Vanishing ALSO RECOMMENDED Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas 1996, PAPER, 297 PAGES, $16.95 Asia correspondent for the New York Times Michael Buckley Crossette portrays Bhutan and neighboring Shangri-la: A Practical Guide to the Ladakh and Sikkim as strongholds of Tantric Himalayan Dream Buddhism in an increasingly homogenized 2008, PAPER, 191 PAGES, $25.99 world. (Item NPL04) With marvelous chapters on the many meanings and myths surrounding Shangri- Broughton Coburn (Editor) La, Buckley’s practical guide covers the Himalaya contenders for this mythical Himalayan 2006, HARD COVER, 256 PAGES, $35.00 paradise in Southwest China, Tibet, Nepal, This beautifully photographed overview of the Sikkim and Bhutan. With many maps and color geology, history and people of the Himalayas photographs. (Item HML84) includes contributions by several Nat Geo photographers, plus introductions by Jimmy Peter Harrison Carter and the Dalai Lama.