Historic Enclosures : Local Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest

2019 Status Report Palampur Palampur Forest Division Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Palampur Forest Division of Dharamshala Forest Circle, Himachal Pradesh Harish Bharti, Aditi Panatu, Kiran and Dr. S. S. Randhawa H. P. State Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan near Udyog Bhawan, Bemloe Shimla-01 0177-2656489 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Forests of Himachal Pradesh........................................................................................................................ 5 Study area and method ....................................................................................................................... 7 District Kangra A Background .................................................................................................................. 7 Location & Geographical– Area ................................................................................................................. 8 Palampur Forest Division- Forest Profile................................................................................................ 9 Name and Situation:- .................................................................................................................................. 9 Geology: ......................................................................................................................................................... 11 -

MMIW" 1. (8Iiira)

..nth Ser... , Vol. ru, No. 11 ...,. July 1., 200t , MMIW" 1. (8IIIra) LOK SABHA DEBATES (Engllah Version) Second Seulon (FourtMnth Lok Sabha) (;-. r r ' ':1" (Vol. III Nos. 11 to 20) .. contains il'- r .. .Ig A g r ~/1'~.~.~~: LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price : Rs. 50.00 EDITORIAL BOARD G.C. MalhotrII Secretary-General Lok Sabha Anand B. Kulkllrnl Joint Secretary Sharda Prued Principal Chief Editor telran Sahnl Chief Editor Parmnh Kumar Sharma Senior Editor AJIt Singh Yed8v Editor (ORIOINAL ENOUSH PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN ENGUSH VERSION AND ORIGINAL HINDI PROCEEDINGS INCLUDED IN HINDI VERSION WILL BE.TREATED AS AUTHORITA11VE AND NOT THE TRANSLATION THEREOF) CONTENTS ,.. (Fourteenth Serles. Vol. III. Second Session. 200411926 (Saka) No. 11. Monday. July 19. 2OO4IAudha, 28. 1121 CSU-) Sua.lECT OBITUARY REFERENCE ...... ...... .......... .... ..... ............................................ .......................... .................................... 1·2 WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS Starred Question No. 182-201 ................................................................. ................ ................... ...................... 2-36 Unstarred Question No. 1535-1735 .................... ..... ........ ........ ...... ........ ......... ................ ................. ........ ......... 36-364 ANNEXURE I Member-wise Index to Starred List of Ouestions ...... ............ .......... .... .......... ........................................ ........... 365 Member-wise Index to Unstarred Ust of Questions ........................................................................................ -

Burlington House

Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Contents Pages 2-5 Oral Programme Pages 6-7 Poster programme Pages 8-33 Oral presentation abstracts (in programme order) Pages 34-63 Poster presentations abstracts (in programme order) Pages 64-65 Conference sponsor information Pages 65-68 Notes 24-26 June 2014 Page 1 Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Oral Programme Tuesday 24 June 2014 09.00 Welcome 11.30 Student presentation from Leh School 11.45 A life in Ladakh Professor (ambassador) Phunchok Stobdan, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses 12.30 Lunch and posters 14.00 Mountaineering in the Himalaya Ang Rita Sherpa, Mountain Institute, Kathmandu, Nepal Session theme: The geological framework of the Himalaya 14.30 Geochemical and isotopic constraints on magmatic rocks – some constraints on collision based on new SHRIMP data Professor Talat Ahmed, University of Kashmir 15.15 Short subject presentations and panel discussion Moderators: Director, Geology & Mining, Jammu & Kashmir State & Director, Geological Survey of India Structural framework of the Himalayas with emphasis on balanced cross sections Professor Dilip Mukhopadhyay, IIT Roorkee Sedimentology Professor S. K. Tandon, Delhi University Petrogenesis and economic potential of the Early Permian Panjal Traps, Kashmir, India Mr Greg Shellnut, National Taiwan Normal University Precambrian Professor D. M. Banerjee, Delhi University 16.00 Tea and posters 16.40 Short subject presentations continued & panel discussion 18.00 Close of day 24-26 June 2014 Page 2 Sutainable Resource Development in the Himalaya Wednesday 25 June 2014 Session theme: Climate, Landscape Evolution & Environment 09.00 Climate Professor Harjeet Singh, JNU, New Delhi 09.30 Earth surface processes and landscape evolution in the Himalaya Professor Lewis Owen, Cincinnati University 10.00 Landscape & Vegetation Dr P. -

Bastar District Chhattisgarh 2012-13

For official use only Government of India Ministry of Water Resources Central Ground Water Board GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF BASTAR DISTRICT CHHATTISGARH 2012-13 Keshkal Baderajpur Pharasgaon Makri Kondagaon Bakawand Bastar Lohandiguda Tokapal Jagdalpur Bastanar Darbha Regional Director North Central Chhattisgarh Region Reena Apartment, II Floor, NH-43 Pachpedi Naka, Raipur (C.G.) 492001 Ph No. 0771-2413903, 2413689 Email- [email protected] GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF BASTAR DISTRICT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE I Location 1. Location : Located in the SSE part of Chhattisgarh State Latitude : 18°38’04”- 20°11’40” N Longitude : 81°17’35”- 82°14’50” E II General 1. Geographical area : 10577.7 sq.km 2. Villages : 1087 nos 3. Development blocks : 12 nos 4. Population : 1411644 Male : 697359 Female : 714285 5. Average annual rainfall : 1386.77mm 6. Major Physiographic unit : Predominantly Bastar plateau 7. Major Drainage : Indravati , Kotri and Narangi rivers 8. Forest area : 1997.68 sq. km ( Reserved) 390.38 sq. km ( Protected) 2588.75 sq. km (Revenue ) Total – 4976.77 sq.km. III Major Soil 1) Alfisols : Red gravelly, red sandy &red loamy 2) Ultisols : Lateritic,Red & yellow soil IV Principal crops 1) Rice : 2024 ha 2) Wheat : 667ha 3) Maize : 2250 ha V Irrigation 1) Net area sown : 315657 sq. km 2) Net and gross irrigated area : 9592 ha a) By dug wells : 2460 no (758 ha) b By tube wells : 1973 no (2184ha) c) By tank/Ponds : 102 no (1442ha) d) By canals : 15 no ( 421 ha) e) By other sources : 4391 ha VI Monitoring wells (by CGWB) 1) Dug wells -

Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (2020-21)

7 MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT & HIGHWAYS ESTIMATES AND FUNCTIONING OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY PROJECTS INCLUDING BHARATMALA PROJECTS COMMITTEE ON ESTIMATES (2020-21) SEVENTH REPORT ___________________________________________ (SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI SEVENTH REPORT COMMITTEE ON ESTIMATES (2020-21) (SEVENTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF ROAD TRANSPORT & HIGHWAYS ESTIMATES AND FUNCTIONING OF NATIONAL HIGHWAY PROJECTS INCLUDING BHARATMALA PROJECTS Presented to Lok Sabha on 09 February, 2021 _______ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI February, 2021/ Magha, 1942(S) ________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ON ESTIMATES (2019-20) (iii) COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE ON ESTIMATES (2020-21) (iv) INTRODUCTION (v) PART - I CHAPTER I Introductory 1 Associated Offices of MoRTH 1 Plan-wise increase in National Highway (NH) length 3 CHAPTER II Financial Performance 5 Financial Plan indicating the source of funds upto 2020-21 5 for Phase-I of Bharatmala Pariyojana and other schemes for development of roads/NHs Central Road and Infrastructure Fund (CRIF) 7 CHAPTER III Physical Performance 9 Details of physical performance of construction of NHs 9 Details of progress of other ongoing schemes apart from 10 Bharatmala Pariyojana/NHDP Reasons for delays NH projects and steps taken to expedite 10 the process Details of NHs included under Bharatmala Pariyojana 13 Consideration for approving State roads as new NHs 15 State-wise details of DPR works awarded for State roads 17 approved in-principle -

Reconciling Drainage and Receiving Basin Signatures of the Godavari River System

Biogeosciences, 15, 3357–3375, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-3357-2018 © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Reconciling drainage and receiving basin signatures of the Godavari River system Muhammed Ojoshogu Usman1, Frédérique Marie Sophie Anne Kirkels2, Huub Michel Zwart2, Sayak Basu3, Camilo Ponton4, Thomas Michael Blattmann1, Michael Ploetze5, Negar Haghipour1,6, Cameron McIntyre1,6,7, Francien Peterse2, Maarten Lupker1, Liviu Giosan8, and Timothy Ian Eglinton1 1Geological Institute, ETH Zürich, Sonneggstrasse 5, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland 2Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Heidelberglaan 2, 3584 CS Utrecht, the Netherlands 3Department of Earth Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Kolkata, 741246 Mohanpur, West Bengal, India 4Division of Geological and Planetary Science, California Institute of Technology, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, California 91125, USA 5Institute for Geotechnical Engineering, ETH Zürich, Stefano-Franscini-Platz 3, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 6Laboratory of Ion Beam Physics, ETH Zürich, Otto-Stern-Weg 5, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland 7Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre AMS Laboratory, Rankine Avenue, East Kilbride, G75 0QF Glasgow, Scotland 8Geology and Geophysics Department, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 86 Water Street, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543, USA Correspondence: Muhammed Ojoshogu Usman ([email protected]) Received: 12 January 2018 – Discussion started: 8 February 2018 Revised: 18 May 2018 – Accepted: 24 May 2018 – Published: 7 June 2018 Abstract. The modern-day Godavari River transports large sediment mineralogy, largely driven by provenance, plays an amounts of sediment (170 Tg per year) and terrestrial organic important role in the stabilization of OM during transport carbon (OCterr; 1.5 Tg per year) from peninsular India to the along the river axis, and in the preservation of OM exported Bay of Bengal. -

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Solan Forest Division of Nahan Circle, Himachal Pradesh Status Report

Temporal Change in Tree Species Composition in Solan Forest Division of Nahan Circle, Himachal Pradesh Status Report 02-Sep-19 Himachal Pradesh Centre on Climate Change (HIMCOSTE), Vigyan Bhawan Bemloe, Shimla-01 H.P. India Harish Bharti, KIran Lata and Aditi Panatu and Dr. S.S. Randhawa Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Forests of Himachal Pradesh .............................................................................................................. 4 Study area and method ............................................................................................................................ 6 District Solan – A Background ............................................................................................................ 6 Methods ................................................................................................................................................... 9 Solan Forest Division – ............................................................................................................................. 9 Assessment techniques .......................................................................................................................... 11 Tree Community-based Variations .................................................................................................. 11 Results & Findings ............................................................................................................................ -

GRMB Annual Report 2018-19 | 59

Government of India Ministry of Jal Shakti Department of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Godavari River Management Board GODAVARI RIVER Origin Brahmagiri near Trimbakeshwar, Nashik Dist., Maharashtra Geographical Area 9.50 % of Total Geographical Area of India Location Latitude – 16°19’ to 22°34’ North Longitude – 73°24’ to 83° 40’ East Boundaries West: Western Ghats North: Satmala hills, Ajanta range and the Mahadeo hills East: Eastern Ghats & Bay of Bengal South: Balaghat & Mahadeo ranges, stretching from eastern flank of Western Ghats & Anantgiri and other ranges of the hills. Ridges separate the Godavari basin from Krishna basin. Catchment Area 3,12,812 Sq.km. Length of the River 1465 km States Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Puducherry (Yanam). Length in AP & TS 772 km Major Tributaries Pravara, Manjira, Manair – Right side of River Purna, Pranhita, Indravati, Sabari – Left side of River Sub- basins Twelve (G1- G12) Select Dams/ Head works Gangapur Dam, Jayakwadi Dam, Srirama Sagar, Sripada across Main Godavari Yellampally, Kaleshwaram Projects (Medigadda, Annaram & Sundilla barrages), Dummugudem Anicut, Polavaram Dam (under construction), Dowleswaram Barrage. Hydro power stations Upper Indravati 600 MW Machkund 120 MW Balimela 510 MW Upper Sileru 240 MW Lower Sileru 460 MW Upper Kolab 320 MW Pench 160 MW Ghatghar pumped storage 250 MW Polavaram (under 960 MW construction) ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 GODAVARI RIVER MANAGEMENT BOARD 5th Floor, Jalasoudha, -

India Upper Indravati Irrigation Project Field Survey

India Upper Indravati Irrigation Project Field Survey: July 2003 1. Project Profile and Japan’s ODA Loan China New Delhi Nepal Bhutan Bangladesh Calcutta Myanmar India Bhubaneshwar Mumbai Project Site Site Map Indravati Main Canal 1.1 Background In India, expansion and improvement of irrigation facilities has been emphasized as a measure to alleviate repeatedly occurring drought damage, as a part of the country’s food self-sufficiency policy. Irrigation facilities are absolutely indispensable in low precipitation regions because the amount of rainfall in India is unpredictable and varies substantially by region, season, and year. Moreover even in heavy precipitation regions, irrigation facilities are extremely important for providing water for agricultural use during the summer season when demand for water is at its peak. The total land area under irrigation in India was scheduled to increase to approximately 57 million hectares by the conclusion of the sixth 5-year plan (March 1985) and to approximately 68 million hectares by the conclusion of the seventh plan (FY 1985- FY1989). The Orissa State Government launched the Upper Indravati Multipurpose Project in 1978 to promote the comprehensive development of the region, which tends to suffer from drought. The project was composed of three units, Unit I (dams and reservoirs), Unit II (irrigation), and Unit III (hydroelectric power). The purpose of this project was to construct a dam on the upper Indravati River, a branch of the Godavari River, discharge the water to the Mahanadi River basin, and produce 600 MW (four generators at 150 MW per generator) of hydroelectric power. In conjunction, the water used to generate the hydroelectric power would then be used for irrigation of approximately 109,000 ha. -

A Review of Methods of Hydrological Estimation at Ungauged Sites in India. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute

WORKING PAPER 130 A Review of Methods of Hydrological Estimation at Ungauged Sites in India Ramakar Jha and Vladimir Smakhtin Postal Address P O Box 2075 Colombo Sri Lanka Location 127, Sunil Mawatha Pelawatta Battaramulla Sri Lanka Telephone +94-11 2880000 Fax +94-11 2786854 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.iwmi.org SM International International Water Management IWMI isaFuture Harvest Center Water Management Institute supportedby the CGIAR ISBN: 978-92-9090-693-3 Institute Working Paper 130 A Review of Methods of Hydrological Estimation at Ungauged Sites in India Ramakar Jha and Vladimir Smakhtin International Water Management Institute IWMI receives its principal funding from 58 governments, private foundations and international and regional organizations known as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Support is also given by the Governments of Ghana, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The authors: Ramakar Jha is a Research Scientist at the National Institute of Hydrology (NIH), Roorkee, India. Vladimir Smakhtin is Principal Scientist in Hydrology and Water Resources at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Colombo, Sri Lanka. Jha, R.; Smakhtin, V. 2008. A review of methods of hydrological estimation at ungauged sites in India. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute. 24p. (IWMI Working Paper 130) / hydrology / models / river basins / runoff / flow / low flows/ flow duration curves/ estimation / flooding /unit hydrograph/ungauged basins/ India / ISBN 978-92-9090-693-3 Copyright © 2008, by IWMI. All rights reserved. Please direct inquiries and comments to: [email protected] ii Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................ v Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Estimating Low Flows and Duration Curves at Ungauged Sites .............................................. -

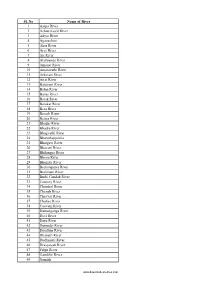

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90 -

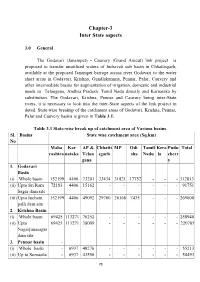

Chapter-3 Inter State Aspects

Chapter-3 Inter State aspects 3.0 General The Godavari (Janampet) - Cauvery (Grand Anicut) link project is proposed to transfer unutilised waters of Indravati sub basin in Chhattisgarh, available at the proposed Janampet barrage across river Godavari to the water short areas in Godavari, Krishna, Gundlakamma, Pennar, Palar, Cauvery and other intermediate basins for augmentation of irrigation, domestic and industrial needs in Telangana, Andhra Pradesh. Tamil Nadu directly and Karnataka by substitution. The Godavari, Krishna, Pennar and Cauvery being inter-State rivers, it is necessary to look into the inter-State aspects of the link project in detail. State-wise breakup of the catchment areas of Godavari, Krishna, Pennar, Palar and Cauvery basins is given in Table 3.1. Table 3.1 State-wise break up of catchment area of Various basins. Sl. Basins State wise catchment area (Sq.km) No Maha Kar AP & Chhatti MP Odi Tamil Kera Pudu Total rashtra nataka Telan sgarh sha Nadu la cherr gana y 1. Godavari Basin (i) Whole basin 152199 4406 73201 33434 31821 17752 - - - 312813 (ii) Upto Sri Ram 72183 4406 15162 - - - - - - 91751 Sagar dam site (iii) Upto Incham 152199 4406 49092 29700 26168 7435 - - - 269000 palli dam site 2. Krishna Basin (i) Whole basin 69425 113271 76252 - - - - - - 258948 (ii) Upto 69425 113271 38009 - - - - - - 220705 Nagarjunasagar dam site 3. Pennar basin - (i) Whole basin - 6937 48276 - - - - - - 55213 (ii) Up to Somasila - 6937 43556 - - - - - - 50493 78 Detailed Project Report of Godavari (Janampet) – Cauvery Grand Anicut) link project dam site 4. Cauvery basin (i) Whole basin - 34273 - - - - 43867 2866 149 81155 (ii) Up to Grand - 34273 - - - - 36008 2866 - 73147 Anicut site Source: Water balance studies of NWDA 3.1 Godavari basin Godavari is the largest river in South India and the second largest in India.