Regional Integration in the Pacific .A W W W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter: Quarter 1, 2021

2021 TRANS-FORMTrans Pacific Union Newsletter 01, Jan-Mar Be a Transformer! On Easter weekend, I was sharing devotions for the youth camp that was held at Navesau Adventist High School in Fiji. What I saw really inspired me. These young people were not there just to have a good time, however were there to transform Navesau. They planted thousands of root crops, vegetables, painted railings and cleaned up the place. At the end of the camp, they donated many things for the school – from equipment for the computer lab, cooking utensils, fencing wire and even family household items. I am sure that it amounted to worth thousands of dollars. I literally saw our Vision Statement come alive. I saw ‘A Vibrant Adventist youth movement, living their hope in Jesus and transforming Navesau’. I know that there were many youth camps around the TPUM who also did similar things and I praise the Lord for the commitment our people have made to transform our Pacific. We can work together to transform our communities, and we can also do it individually. Jesus Christ illustrates this with this Parable in Matthew 13:33: “The kingdom of heaven is like yeast…mixed into…flour until it is worked all through the dough.” Jesus invites us to imagine the amazing properties of a little bit of yeast; it can make dough rise so that it bakes into wonderful bread. Like yeast, only a small expression of the kingdom of Jesus Christ in our lives can make an incredible impact on the lives and culture of people around us. -

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu

Vanuatu Mission, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. Photo courtesy of Nos Terry. Vanuatu Mission BARRY OLIVER Barry Oliver, Ph.D., retired in 2015 as president of the South Pacific Division of Seventh-day Adventists, Sydney, Australia. An Australian by birth Oliver has served the Church as a pastor, evangelist, college teacher, and administrator. In retirement, he is a conjoint associate professor at Avondale College of Higher Education. He has authored over 106 significant publications and 192 magazine articles. He is married to Julie with three adult sons and three grandchildren. The Vanuatu Mission is a growing mission in the territory of the Trans-Pacific Union Mission of the South Pacific Division. Its headquarters are in Port Vila, Vanuatu. Before independence the mission was known as the New Hebrides Mission. The Territory and Statistics of the Vanuatu Mission The territory of the Vanuatu Mission is “Vanuatu.”1 It is a part of, and reports to the Trans Pacific Union Mission which is based in Tamavua, Suva, Fiji Islands. The Trans Pacific Union comprises the Seventh-day Adventist Church entities in the countries of American Samoa, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Niue, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. The administrative office of the Vanuatu Mission is located on Maine Street, Nambatu, Vila, Vanuatu. The postal address is P.O. Box 85, Vila Vanuatu.2 Its real and intellectual property is held in trust by the Seventh-day Adventist Church (Vanuatu) Limited, an incorporated entity based at the headquarters office of the Vanuatu Mission Vila, Vanuatu. The mission operates under General Conference and South Pacific Division (SPD) operating policies. -

2Nd Quarter 2016

MissionCHILDREN’S 2016 • QUARTER 2 • SOUTH PACIFIC DIVISION www.AdventistMission.org Contents On the Cover: Eleven-year-old Ngatia started a children’s Sabbath School under the trees. When the group couldn’t meet there anymore, God provided a very unusual meeting place. COOK ISLANDS FIJI 4 Life on the Island/ April 2 22 The Mystery of the Matches | June 4 24 Praying for Parents | June 11 SOLOMON ISLANDS 6 The Snooker Hut Girl| April 9 NEW ZEALAND 8 Giving the Invitation, Part 1 | April 16 26 Working With Jesus | June 18 10 Giving the Invitation, Part 2 | April 23 RESOURCES 12 The Children of Ngalitatae | April 30 28 Thirteenth Sabbath Program | June 25 PAPUA NEW GUINEA 30 Future Thirteenth Sabbath Projects 14 The Early Bird | May 7 31 Flags 16 Helping People | May 14 32 Recipes and Activities 18 Angels Are Real! | May 21 35 Resources/Masthead 20 The Unexpected Church | May 29 36 Map Your Offerings at Work The first quarter 2013, Thirteenth Sabbath Offering helped to build three Isolated Medical Outpost clinics in some of the most remote areas of Papua New Guiena, Vanuatu, and the Solomon Islands. These clinics provide the only easily accessible medical service to thousands of people living in these areas and offer a Seventh- day Adventist presence into these previously unentered areas. Thank you for your generosity! Above: The Buhalu Medical Clinic and staff house in Papua New Guiena were made possible in part through the Thirteenth Sabbath Offering. South Pacific Division ISSION ©2016 General Conference of M Seventh-day Adventists®• All rights reserved 12501 Old Columbia Pike, DVENTIST Silver Spring, MD 20904-6601 A 800.648.5824 • www.AdventistMission.org 2 Dear Sabbath School Leader, This quarter features the South Pacific and seashells. -

Votes & Proceedings

Votes & Proceedings Of the Sixteenth Parliament No. 35 First Sitting of the Twenty-eighth Meeting 10.00 a.m. Friday, 22nd December 2006 1. The House met on Friday, 22nd December 2006 at 10 a.m. in accordance with the resolution made by the House on Thursday, 9th November 2006. 2. The Hon. Valdon K. Dowiyogo, M.P., Speaker of Parliament, took the Chair and read Prayers. 3. Statements from the Chair (i) ‘Members of the House, before we proceed with our normal business of the day, I have four statements to be made to this august House. As Members might be aware that the Parliament of Nauru has been provided with two Toyota Prado diesel four-wheel vehicles as a grant by the Government of India. These vehicles will serve the long term use of the Parliament in smoothening its work and facilitating the Members in their official duties. This project was taken by me with the then Minister for External Affairs who is also the Prime Minister of India and I am happy that they have acceded to my request. I have also regulated the use of the vehicle within the Parliament Secretariat in order to achieve the highest levels of efficiency and diligence. I would also like to state in no uncertain terms that this assistance would not have come without the endeavours of our Department of Foreign Affairs who had over the years strengthened the bilateral ties with India and the Minister, Hon. David Adeang, who talked to the Deputy Minister of External Affairs, Government of India, Hon. -

The Transilient Fiji- Indian Diaspora Engagement and Assimilation in Transnational Space

Transnational Indian Diaspora Engagement and development: The transilient Fiji- Indian diaspora engagement and assimilation in transnational space Manoranjan Mohanty The University of the South Pacific, Fiji Abstract The Indian immigrants or ‘girmitiyas’ under British indenture labour system have gradually transformed to Indian Diaspora in transnational space be it from Mauritius, British Guiana, Trinidad, South Africa, Fiji, Jamaica or Suriname. The onset of globalization has stimulated the contemporary diasporic movements and social and economic networking and in turn, a greater diasporic engagement... Cheaper means of communication and growth of mass media and ICT, have contributed much to diaspora movement across border, creating ‘transnational communities’, globally. Today, the diaspora has been emerged as a new resource and an agent of change and development. It has been a major source of remittance, investment, and human and social capital and has been emerging as an alternative development strategy. The role of diaspora in contemporary development of both country of origin and country of residence draws greater attention today than ever before. The ‘girmitiyas’ in Fiji that arrived between 1879-1916 have undergone generational changes, and gradually transformed to distinct Fijian-Indian Diaspora within Fiji and abroad. These ‘transient’ and ‘translient’ migrants, through a ‘double’ and ‘triple’ chain- migration have formed distinct transnational Fijian-Indian diaspora especially in the Pacific- Rim metropolitan countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and USA. They are deeply engaged in social, cultural and economic development and assimilated in transnational space. Bollywood films have helped binding Indian diaspora especially Fiji- Indians abroad who have maintained Indian cultural identity in the global space. -

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Update

The Dynamic Gravity Dataset: Technical Documentation Update Note Version 2.00 Abstract This document provides an update to the technical documentation for the Dynamic Gravity dataset, describing changes from Version 1.00 to Version 2.00. For full descrip- tion of the contents and construction of the dataset, see full technical documentation for Version 1.00 on the dataset page at https://www.usitc.gov/data/gravity/dgd.htm. This documentation is the result of ongoing professional research of USITC Staff and is solely meant to represent the opinions and professional research of individual authors. It is not meant to represent in any way the views of the U.S. International Trade Commission or any of its individual Commissioners. It is circulated to promote the active exchange of ideas between USITC Staff and recognized experts outside the USITC, professional development of Office Staff and increase data transparency by encouraging outside professional critique of staff research. Please address all correspondence to [email protected]. 1 1 Introduction The Dynamic Gravity dataset contains a collection of variables describing aspects of countries and territories as well as the ways in which they relate to one-another. Each record in the dataset is defined by a pair of countries or territories and a year. The records themselves are composed of three basic types of variables: identifiers, unilateral character- istics, and bilateral characteristics. The updated dataset spans the years 1948{2019 and reflects the dynamic nature of the globe by following the ways in which countries have changed during that period. The resulting dataset covers 285 countries and territories, some of which exist in the dataset for only a subset of covered years.1 1.1 Contents of the Documentation The updated note begins with a description of main changes to the dataset from Version 1.00 to Version 2.00 in section 1.2 and a table of variables available in Version 1.00 and Version 2.00 of the dataset in section 1.3. -

The Case of the Fiji Islands

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 12-13-2011 Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands Sudarsan Kant University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kant, Sudarsan, "Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands" (2011). Dissertations. 395. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/395 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Explaining Investment Policies in Microstates: The Case of the Fiji Islands By Sudarsan Kant A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Missouri-St. Louis In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy In Political Science November 15, 2011 Advisory Committee Kenneth Thomas, PhD., (Chair) Nancy Kinney, Ph.D. Eduardo Silva, Ph.D. Daniel Hellinger, Ph.D. Abstract . Prevailing theories have failed to take into account the development of policy and institutions in microstates that are engineered to attract investments in areas of comparative advantage as these small islands confront the challenges of globalization and instead have emphasized migration, remittances and foreign aid (MIRAB) as an explanation for the survival of microstates in the global economy. This dissertation challenges the MIRAB model as an adequate explanation of investment strategy in microstates and argues that comparative advantage is a better theory to explain policy behavior of microstates. -

History of the Pacific Islands Studies Program at the University of Hawaii: 1950-198

HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII: 1950-198 by AGNES QUIGG Workinq Paper Series Pacific Islands Studies Program canters for Asian cmd Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa EDITOR'S OOTE The Pacific Islands Studies Program. often referred to as PIP, at the University of Hawaii had its beginnings in 1950. These were pre-statehood days. The university was still a small territorial institution (statehood came in 1959), and it is an understatement to say that the program had very humble origins. Subsequently, it has had a very checkered history and has gone through several distinct phases. These and the program's overall history are clearly described and well analyzed by Ms. Agnes Quigg. This working paper was originally submitted by Ms. Quigg as her M.A. thesis in Pacific Islands Studies. Ms. Quigg' is a librarian in the serials division. Hamnlton Library, University of Hawaii. Earlier in this decade, she played a crucial role in the organization of the microfilming of the archives of the U.S. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, Office of the High CommiSSioner, Saipan, Northern Marianas. The archives are now on file at Hamilton Library. Formerly, Ms. Quigg was a librarian for the Kamehameha Schools in Honolulu. R. C. Kiste Director Center for Pacific Islands Studies THE HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES PROGRAM AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII: 1950-1986 By Agnes Quigg 1987 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a number of people who have helped me to complete my story. Judith Hamnett aided immeasurably in my knowledge of the early years of PIP, when she graciously turned over her work covering PIP's first decade. -

Wetlands of the Pacific Island Region

Wetlands Ecol Manage DOI 10.1007/s11273-008-9097-3 ORIGINAL PAPER Wetlands of the Pacific Island region Joanna C. Ellison Received: 1 August 2007 / Accepted: 19 April 2008 Ó Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008 Abstract The wetlands of 21 countries and territo- remain in this region. Only five countries are signato- ries of the Pacific Islands region are reviewed: ries to the Ramsar convention on wetlands, and this American Samoa, Cook Islands, Federated States of only recently with seven sites. Wetland managers have Micronesia, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Kiribati, identified the need for community education, baseline Marshall Islands, Nauru, New Caledonia, Niue, surveys and monitoring, better legislation and policy Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, for wetland management, and improved capacity of Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, local communities to allow the wise use of their Vanuatu, and Wallis and Futuna. The regions’ wet- wetlands. lands are classified into seven systems: coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangrove swamps, riverine, lacustrine, Keywords Oceania Á Wetland Á Pacific Islands Á freshwater swamp forests and marshes. The diversity Seagrass Á Mangrove Á Coral reef Á River Á Lake Á of species in each of these groups is at near global Freshwater swamp Á Marsh maxima at the west of the region, with decline towards the east with increasing isolation, and decreasing island size and age. The community structure is unique Introduction in each country, and many have endemic species with the habitat isolation that epitomises this island region. The Pacific Islands region (Fig. 1) while comprising There remain, however, some serious gaps in basic almost 38.5 million km2, supports less than 0.6 mil- inventory, particularly in freshwater biodiversity. -

Regional Strategy Paper and Regional Indicative Programme

EUROPEAN COMMUNITY - PACIFIC REGION Regional Strategy Paper and Regional Indicative Programme 2008-2013 The European Commission and the Pacific region, represented by the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, hereby agree as follows: (1) The European Commission (represented by Stefano Manservisi, Director-General for Development and Relations with ACP countries, Roberto Ridolfi and Wiepke Van der Goot, respectively former and present Head of the Delegation of the European Commission in the Pacific) and the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS) (represented by Greg Urwin and Tuiloma Neroni Slade, respectively former and present Secretary-General, Iosefa Maiawa, Feleti Teo and Peter Forau, Deputies Secretary-General), hereinafter referred to as the Parties, held discussions in Suva from March 2006 to September 2008 with a view to determining the general direction of cooperation for the period 2008-2013. The European Investment Bank, represented by David Crush, Head of Division, Pacific and Caribbean, was consulted. During these discussions, the Regional Strategy Paper, including an Indicative Progranune of Community Aid in favour of the Pacific, was drawn up in accordance with the provisions of Articles 8 and 10 of Annex IV to the ACP-EC Partnership Agreement, signed in Cotonou on 23 June 2000 and revised in Luxembourg on 25 June 2005. These discussions complete the progranuning process in the Pacific region. The Pacific region includes the following countries: Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Timor Leste, Tonga, Tuvalu and Vanuatu. The Regional Strategy Paper and the Indicative Progranune are attached to this document. (2) As regards the indicative progranunable financial resources which the Community intends to make available to the Pacific region for the period 2008-2013, an amount of €95 million is earmarked for the allocation referred to in Article 9 of Annex IV to the ACP-EC Partnership Agreement. -

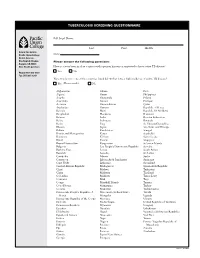

Tuberculosis Screening Questionnaire

TUBERCULOSIS SCREENING QUESTIONNAIRE Full Legal Name: Last First Middle Return this form to: Pacific Union College Date: Health Services One Angwin Avenue Please answer the following questions: Angwin, CA 94508 Attn: Health Services Have you ever been in close contact with a person known or suspected to have active TB disease? Yes No Phone (707) 965-6339 Fax (707) 965-6243 Were you born in one of the countries listed below that have a high incidence of active TB disease? Yes (Please circle) No Afghanistan Ghana Peru Algeria Guam Philippines Angola Guatemala Poland Argentina Guinea Portugal Armenia Guinea-Bissau Qatar Azerbaijan Guyana Republic of Korea Bahrain Haiti Republic Of Moldova Bangladesh Honduras Romania Belarus India Russian Federation Belize Indonesia Rwanda Benin Iraq St. Vincent/Grenadines Bhutan Japan Sao Tome and Principe Bolivia Kazakhstan Senegal Bosnia and Herzegovina Kenya Seychelles Botswana Kiribati Sierra Leone Brazil Kuwait Singapore Brunei Darussalam Kyrgyzstan Solomon Islands Bulgaria Lao People’s Democratic Republic Somalia Burkina Faso Latvia South Africa Burundi Lesotho Sri Lanka Cambodia Liberia Sudan Cameroon Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Suriname Cape Verde Lithuania Swaziland Central African Republic Madagascar Syrian Arab Republic Chad Malawi Tajikistan China Malaysia Thailand Colombia Maldives Timor-Leste Comoros Mali Togo Congo Marshall Islands Tunisia Cote d’Ivoire Mauritania Turkey Croatia Mauritius Turkmenistan Democratic People’s Republic of Micronesia (Federal State) Tuvalu Korea Mongolia Uganda Democratic -

Challenges, Perils, Rewards in Seven Pacific Island Countries

‘BACK TO THE SOURCE’ 6. Investigative journalism: Challenges, perils, rewards in seven Pacific Island countries ABSTRACT This article appraises the general state of investigative journalism in seven Pacific Island countries—Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu—and asserts that the trend is not encouraging. Journalism in general, and investigative journalism in particular, has struggled due to harsher legislation as in military-ruled Fiji; beatings and harassment of journalists as in Vanuatu; and false charges and lawsuits targeting journalists and the major newspaper company in the Cook Islands. Corruption, tied to all the major political upheavals in the region since independence, is also discussed. Threats to investigative journalism, like the ‘backfiring effect’ and ‘anti-whistleblower’ law are examined, along with some investigative journalism success case studies. SHAILENDRA SINGH University of the South Pacific HIS article explores investigative journalism practice and capacity in seven Pacific Island countries, namely Cook Islands, Fiji, Papua TNew Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu. It starts with a consideration of Fiji, which adopted stern media laws following the December 2006 coup. Fiji’s situation is the most drastic in the region, and is studied in greatest detail. The article then considers the other six countries. Unlike Fiji, these countries are democracies in one sense or another. But their journalists still face harassment, especially if they criticise government. Some of the more blatant cases of persecution are revisited. Aside from state pressure, certain structural, environmental and organisational factors pecu- liar to the region also hinder investigative journalism. These are discussed, with some suggestions for mitigation.