Our Evolving Countryside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the Website

2008 Issue Number 1 SHTAV NEWS Journal of The Association of small Historic Towns and Villages of the UK above RICHMOND YORKSHIRE Understanding Market Towns The Village 1 some family lines to be followed down the centuries. The writing of this book grew out of a relatively simple request by the Atherstone Civic Society, in 2002/3, for funds to preserve an ancient animal pound. The Countryside Agency, and subsequently the Heritage Lottery Fund, insisted that a wider project be embarked upon, one that would involve the entire community. The HART project was born. Additional funding came from Nationwide (through the Countryside Agency), Advantage West Midlands and Atherstone & Polesworth Market Towns Programme. From the £35,000 in grants, funds were used to pay for the first professional historic building survey of Atherstone town centre. The services of a trained archivist were also employed. The town has benefited unexpectedly from the information these specialists were able to provide, for example by now having a survey of all the town's buildings of historic architectural significance. The size of the task undertaken by the HART group is reflected by the credits list of over 50 team members, helpers or professional advisers. The major sponsors required the initial book to be accessible and readable by ONCE UPON A TIME book is to be in an 'easy-reading format'. everyone in the community. Local educa- IN ATHERSTONE That has certainly been achieved. But that tionalist Margaret Hughes offered to write Author: Margaret Hughes term belies the depth of research and skill the history, so research information was Publisher: Atherstone Civic Society of presentation, which are what makes the passed to her as it came to light. -

East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate

East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove Local Aggregate Assessment December 2016 East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate Assessment, December 2016 Contents Executive Summary 2 1 Introduction 7 2 Geology and mineral uses 9 3 Demand 11 4 Supply 17 5 Environmental constraints 29 6 Balance 31 7 Conclusions 35 A Past and Future Development 37 B Imports into plan area 41 Map 1: Geological Plan including locations of aggregate wharves and railheads, and existing mineral sites 42 Map 2: Origin of aggregate imported, produced and consumed in East Sussex and Brighton & Hove during 2014 44 Map 3: Sand and gravel resources in the East English Channel and Thames Estuary (Source: Crown Estate) 46 Map 4: Recycled and secondary aggregates sites 48 2 East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove, Local Aggregate Assessment, December 2016 Executive Summary Executive Summary Executive Summary The first East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove Local Aggregate Assessment (LAA) was published in December 2013. The LAA has been updated annually and is based on the Plan Area for the East Sussex, South Downs and Brighton & Hove Waste & Minerals Plan which was adopted in February 2013. This document represents the fourth LAA for the mineral planning authorities of East Sussex County Council, Brighton & Hove City Council and the South Downs National Park Authority and examines updates to the position on aggregates supply and demand since the time of last reporting in 2015. The first three LAAs concluded that a significant proportion of local consumption was derived from either marine dredged material, crushed rock or land won aggregates extracted from outside the Plan Area. -

Roman Lead Sealings

Roman Lead Sealings VOLUME I MICHAEL CHARLES WILLIAM STILL SUBMITTED FOR TIlE DEGREE OF PILD. SEPTEMBER 1995 UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY (L n") '3 1. ABSTRACT This thesis is based on a catalogue of c. 1800 records, covering over 2000 examples of Roman lead sealings, many previously unpublished. The catalogue is provided with indices of inscriptions and of anepigraphic designs, and subsidiary indices of places, military units, private individuals and emperors mentioned on the scalings. The main part of the thesis commences with a history of the use of lead sealings outside of the Roman period, which is followed by a new typology (the first since c.1900) which puts special emphasis on the use of form as a guide to dating. The next group of chapters examine the evidence for use of the different categories of scalings, i.e. Imperial, Official, Taxation, Provincial, Civic, Military and Miscellaneous. This includes evidence from impressions, form, texture of reverse, association with findspot and any literary references which may help. The next chapter compares distances travelled by similar scalings and looks at the widespread distribution of identical scalings of which the origin is unknown. The first statistical chapter covers imperial sealings. These can be assigned to certain periods and can thus be subjected to the type of analysis usually reserved for coins. The second statistical chapter looks at the division of categories of scalings within each province. The scalings in each category within each province are calculated as percentages of the provincial total and are then compared with an adjusted percentage for that category in the whole of the empire. -

The Roman Fort at South Shields (Arbeia): a Study in the Spatial Patterning of the Faunal Remains

Durham E-Theses The roman fort at south shields (arbeia): a study in the spatial patterning of the faunal remains Stokes, Paul Robert George How to cite: Stokes, Paul Robert George (1996) The roman fort at south shields (arbeia): a study in the spatial patterning of the faunal remains, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5330/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Paul Robert George Stokes The Roman Fort at South Shields (Arbeia) A Study in the Spatial Patterning of the Faunal Remains Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts March 1996 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

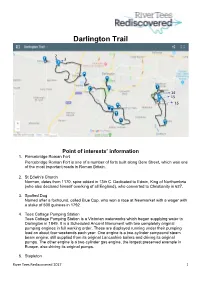

Darlington Trail

Darlington Trail 2 3 4 6 5 7 13 14 15 16 10 8 9 5 11 12 17 Point of interests’ information 1. Piercebridge Roman Fort Piercebridge Roman Fort is one of a number of forts built along Dere Street, which was one of the most important roads in Roman Britain. 2. St Edwin’s Church Norman, dates from 1170, spire added in 13th C. Dedicated to Edwin, King of Northumbria (who also declared himself overking of all England), who converted to Christianity in 627. 3. Spotted Dog Named after a foxhound, called Blue Cap, who won a race at Newmarket with a wager with a stake of 500 guineas in 1792. 4. Tees Cottage Pumping Station Tees Cottage Pumping Station is a Victorian waterworks which began supplying water to Darlington in 1849. It is a Scheduled Ancient Monument with two completely original pumping engines in full working order. These are displayed running under their pumping load on about four weekends each year. One engine is a two-cylinder compound steam beam engine, still supplied from its original Lancashire boilers and driving its original pumps. The other engine is a two-cylinder gas engine, the largest preserved example in Europe, also driving its original pumps. 5. Stapleton River Tees Rediscovered 2017 1 6. South Park It was known originally as Belasses Park, then the People’s Park. Eventually, it came to be called South Park, and currently extends to some 26 hectares (91 acres). It has always been a popular recreational venue and, after recent Heritage Lottery funding, is more attractive than ever – playing host to regular concerts and other events. -

Environmental Importance of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty

Debate on 3rd April: Environmental Importance of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty This Library Note outlines the origins and development of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It provides a brief summary of the current role and funding of these areas with more detailed coverage of recent evaluations of their environmental importance. Elizabeth Shepherd Date 31st March 2008 LLN 2008/010 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. 1. Introduction The aim of this paper is to provide a summary of the key milestones in the development of policy on Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) and to present the recent evidence available on their significance in environmental terms. It does not cover perceived threats to AONBs, such as wind farm and road developments. AONBs include “some of our finest countryside … [t]hey are living and working landscapes protected by law. They are inhabited by thousands of people and are loved and visited by many thousands more” (Countryside Agency Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plans: A Guide, 2001, p. 9). Their primary statutory purpose is to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the landscape: The statutory definition of ‘Natural Beauty’ includes flora, fauna and geological and physiographic features. -

May 2017 Student Association

May 2017 Student Association Formation of the QESFC Interact Club JUNE 2016 In June 2016, plans to set up the QESFC Interact Club were discussed and the club was officially formed on 17 November 2016 in association with the Darlington Rotary Club. The first board meeting took place in September 2016, where the Interact Club’s Constitution was discussed. This outlined expectations, guidelines and rules that the club must follow including the expectation that the group meets twice per month and organises two major projects annually, one designed to serve the College or community and the other to promote international understanding. It also outlined the structure of the club including a President, Vice President, Secretary and Treasurer plus other additional members. It seemed appropriate to ask the Student Association if they wanted to get involved and they were all very keen to participate. In November, Lewis Maddison (President); Charlotte Ferguson (Vice President); Beth MacNamara (Secretary); Nathan Johnson-Small (Marketing and Environmental Coordinator); Ebony Chaplin (Health Coordinator) and Sarah Currie (Common Room Coordinator) attended the Annual Rotary Ball as representatives of the QE Interact Club, which took place at the King’s Hotel. Charlotte said, “I thoroughly enjoyed the evening and it was great to socialise with the Rotarians and hear first-hand about all the amazing community work they get involved with.” Macmillan coffee morning SEPTEMBER 2016 In September, the Student Association sold a selection of home baked cakes, biscuits, Malteser tiffin and Krispy Kreme doughnuts in the Student Common Room to raise funds for Macmillan Cancer Support. For many years QE has taken part in the annual ‘World’s Biggest Coffee Morning’ and it was a really successful event with the Krispy Kreme doughnuts selling out by lunchtime, raising £108.38 in total. -

The Britons in Late Antiquity: Power, Identity And

THE BRITONS IN LATE ANTIQUITY: POWER, IDENTITY AND ETHNICITY EDWIN R. HUSTWIT Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Bangor University 2014 Summary This study focuses on the creation of both British ethnic or ‘national’ identity and Brittonic regional/dynastic identities in the Roman and early medieval periods. It is divided into two interrelated sections which deal with a broad range of textual and archaeological evidence. Its starting point is an examination of Roman views of the inhabitants of the island of Britain and how ethnographic images were created in order to define the population of Britain as 1 barbarians who required the civilising influence of imperial conquest. The discussion here seeks to elucidate, as far as possible, the extent to which the Britons were incorporated into the provincial framework and subsequently ordered and defined themselves as an imperial people. This first section culminates with discussion of Gildas’s De Excidio Britanniae. It seeks to illuminate how Gildas attempted to create a new identity for his contemporaries which, though to a certain extent based on the foundations of Roman-period Britishness, situated his gens uniquely amongst the peoples of late antique Europe as God’s familia. The second section of the thesis examines the creation of regional and dynastic identities and the emergence of kingship amongst the Britons in the late and immediately post-Roman periods. It is largely concerned to show how interaction with the Roman state played a key role in the creation of early kingships in northern and western Britain. The argument stresses that while there were claims of continuity in group identities in the late antique period, the socio-political units which emerged in the fifth and sixth centuries were new entities. -

Chichester District AONB Landscape Capacity Study for Chichester District Council

Landscape Architecture Masterplanning Ecology Chichester District AONB Landscape Capacity Study for Chichester District Council October 2009 hankinson duckett associates t 01491 838175 f 01491 838997 e [email protected] w www.hda-enviro.co.uk The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BA Hankinson Duckett Associates Limited Registered in England & Wales 3462810 Registered Office: The Stables, Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Wallingford, OX10 8BA Contents Page 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 6 2 Approach ................................................................................................................................ 7 3 Landscape Character Context ........................................................................................... 10 3.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 10 3.2 The Landscape of Chichester District ................................................................................... 10 3.3 Local Landscape Characterisation ........................................................................................ 11 4 Landscape Structure Analysis ........................................................................................... 13 4.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

The South Downs National Park Inspector's Report

Report to the Secretary of State The Planning Inspectorate Temple Quay House for Environment, Food and 2 The Square Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6PN Rural Affairs GTN 1371 8000 by Robert Neil Parry BA DIPTP MRTPI An Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Environment, Date: Food and Rural Affairs 28 November 2008 THE SOUTH DOWNS NATIONAL PARK INSPECTOR’S REPORT (2) Volume 1 Inquiry (2) held between 12 February 2008 and 4 July 2008 Inquiry held at The Chatsworth Hotel, Steyne, Worthing, BN11 3DU Temple Quay House 28 November 2008 2 The Square Temple Quay Bristol BS2 9DJ To the Right Honourable Hilary Benn MP Secretary of State for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Sir South Downs National Park (Designation) Order 2002 East Hampshire Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (Revocation) Order 2002 Sussex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (Revocation) Order 2002 South Downs National Park (Variation) Order 2004 The attached report relates to the re-opened inquiry into the above orders that I conducted at the Chatsworth Hotel, Worthing. The re-opened inquiry sat on 27 days between 12 February 2008 and 28 May 2008 and eventually closed on 4 July 2008. In addition to the inquiry sessions I spent about 10 days undertaking site visits. These were normally unaccompanied but when requested they were undertaken in the company of inquiry participants and other interested parties. I held a Pre- Inquiry meeting to discuss the administrative and procedural arrangements for the inquiry at Hove Town Hall on 12 December 2007. The attached report takes account of all of the evidence and submissions put forward at the re-opened inquiry together with all of the representations put forward in writing during the public consultation period. -

Publication Draft

DARLINGTON INFRASTRUCTURE DELIVERY PLAN: PUBLICATION DRAFT Darlington Local Development Framework July 2010 Publication Infrastructure Delivery Plan Darlington Local Development Framework July 2010 CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 5 Purpose of the Document 5 What is Infrastructure? 5 Policy Context 7 The Core Strategy 8 Local Context 9 Planning Obligations 9 Approach 10 2.0 PHYSICAL INFRASTRUCTURE 12 TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE 12 The Borough’s Road Network 12 Rail Based Transport 15 Cycling Walking and Other Public Transport Measures 18 Air Travel 19 UTILITIES INFRASTRUCTURE 21 Gas Supply 22 Electricity Supply 22 Water Supply, Waste Water Distribution and Sewerage Network 22 Telecommunications 23 Waste Management 24 Renewable Energy 24 Flood Management 24 3.0 SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY INFRASTRUCTURE 26 HEALTH CARE PROVISION 26 EDUCATION AND LIBRARIES 28 Early Years Provision 28 School Education 29 Further Education 32 Libraries 33 HOUSING 34 Affordable Housing 34 Improvements to Existing Housing 36 Older Persons Accommodation 37 ADULT AND CHILDREN SOCIAL CARE FACILITIES 38 ACCOMMODATING TRAVELLING GROUPS 38 SPORT AND RECREATION PROVISION 39 Playing Pitches 39 Indoor and Outdoor Sports Facilities 41 CULTURAL AND HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS 43 Hotel provision 44 EMERGENCY SERVICES 45 4.0 GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE 47 Green Corridors 47 Parks and Gardens 47 Cemeteries, Churchyards and Burial Grounds 48 Children and Young People’s Provision 49 Civic Spaces 50 Natural and Semi Natural Greenspace 50 Informal Open Space 51 Landscape Amenity 51 Urban Fringe 51 Allotments -

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plans a Guide

Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plans A guide Working for people and places in rural England The Countryside Agency The Countryside Agency is the statutory body working: • to conserve and enhance England’s countryside; • to spread social and economic opportunity for the people who live there; • to help everyone, wherever they live and whatever their background, to enjoy the countryside and share in this priceless national asset. The Countryside Agency will work to achieve the very best for the English countryside – its people and places, by: • influencing those whose decisions affect the countryside through our expertise, our research and by spreading good practice by showing what works; • implementing specific work programmes reflecting priorities set by Parliament, the Government and the Agency Board. To find out more about our work, and for information about the countryside, visit our website: www.countryside.gov.uk The Countryside Agency publications catalogue (CA2) includes a full listing of all our publications. Contact Countryside Agency Publications for a free copy. Cover photograph: Shropshire Hills AONB. CA/David Woodfall. Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plans A guide Distributed by: Countryside Agency Publications PO Box 125 Wetherby West Yorkshire LS23 7EP Telephone 0870 120 6466 Fax 0870 120 6467 Email: [email protected] Website www.countryside.gov.uk Minicom 0870 120 7405 (for the hard of hearing) © Countryside Agency November 2001 AONB Management Plans: A guide Foreword The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 created a new statutory duty/on AONB local authorities to publish AONB Management Plans. This requirement, alongside other new obligations on a wide range of bodies to have regard for AONB purposes, represents a great opportunity to develop and strengthen local partnerships that are the essence of positive AONB management.