Awareness Itself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Ajaan-Goeff-Retreat

Bellingham Insight Meditation Society One Day Online Retreat Clinging and the End of Clinging A One Day Online Retreat with Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Ajaan Geoff) September 12th, 2020 9 am to 4 pm (PDT) When the Buddha formulated the first noble truth — the truth of suffering — he didn’t say something useless like “Life is Suffering,” and he didn’t say something vague and obvious like “There is suffering.” Instead, he said something more useful and insightful: suffering is the five clinging aggregates. As he explained, the problem isn’t with the aggregates, it’s with the clinging. So when he described the focus of his teaching as suffering and the end of suffering, he was basically saying that it was focused on clinging and the end of clinging. If we want to understand his teaching, we have to understand what clinging is, why it’s suffering, and how clinging can be used to put an end to clinging. This is the purpose of this two-part class. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff) has been a Theravada Buddhist monk since 1976. After studying in Thailand with Ajaan Fuang Jotiko for ten years, he returned to the U.S. in 1991 to help found Metta Forest Monastery in the mountains north of San Diego where he is currently Abbot. Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s writing includes The Paradox of Becoming, The Mind Like Fire Unbound, The Wings to Awakening Straight from the Heart (Venerable Acariya Boowa), Right Mindfulness, and The Craft of the Heart (Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo). He has also translated many meditation guides by Thai forest masters as well as numerous scriptural texts from the Pali canon. -

RIGHTVIEW Quarterly Dharma in Practice Fall 2007

RIGHTVIEW Quarterly Dharma in Practice fall 2007 Master Ji Ru, Editor-in-Chief Xianyang Carl Jerome, Editor Carol Corey, Layout and Artwork Will Holcomb, Production Assistance Subscribe at no cost at www.rightviewonline.org or by filling out the form on the back page. We welcome letters and comments. Write to: [email protected] or the address below RIGHTVIEW QUARTERLY is published at no cost to the subscriber by the Mid-America Buddhist Association (MABA) 299 Heger Lane Augusta, Missouri 63332-1445 USA The authors of their respective articles retain all copyrights More artwork by Carol Corey may be seen at www.visualzen.net Our deepest gratitude to Concept Press in New York City, and Mr. King Au for their efforts and generosity in printing and distributing Rightview Quarterly. VISIT www.RightviewOnline.org ABOUT THE COVER: This Japanese handscroll from the mid-12th century records in opulent gold calligraphy the text of the Heart Sutra. The scroll originally came from a large set of the Buddhist scriptural canon, probably numbering more than 5,000 scrolls, that were dedicated to Chuson-ji Temple in present-day Iwate Prefecture. Chuson-ji was founded in 1105 and the Northern Fujiwara warriors lavishly patronized the temple until their demise at the end of that century. Copyright, The British Museum, published with permission. P r e s e n t V i e w Editor Xianyang Carl Jerome explains here that reconciliation is our practice, and addresses this idea again in the context of Buddhist social engagement in the article Those Pictures on page 24. -

La Tradition De La Forêt

Page 1 sur 20 Version provisoire [Claude Le Ninan, septembre 2010] La tradition de la forêt Quelques repères [attente autre photo forêt Thaïlande] Photos Historique de la tradition de la forêt en Thaïlande et en occident Moines et nonnes de la tradition de la forêt Sources et liens Page 2 sur 20 Photos Anciennes Récentes [attente autres photos Thaïlande] Page 3 sur 20 Historique de la tradition de la forêt en Thaïlande et en occident Les coutumes des Etres Nobles Thanissaro Bhikkhu - 1999 - A travers son histoire, le bouddhisme a fonctionné comme une force civilisatrice. Par exemple, ses enseignements sur le karma - le principe selon lequel toutes les actions intentionnelles ont des conséquences - ont enseigné la moralité et la compassion à de nombreuses sociétés. Mais à un niveau plus profond, le bouddhisme a toujours chevauché la ligne de partage entre la civilisation et les étendues sauvages. Le Bouddha lui-même a réalisé l'Eveil dans une forêt, a donné son premier sermon dans une forêt, et est décédé dans une forêt. Les qualités d'esprit dont il avait besoin afin de survivre physiquement et mentalement alors qu'il allait, sans arme, dans les étendues sauvages jouèrent un rôle clé dans sa découverte du Dhamma. Elles incluaient la résistance, la détermination, être en attitude d'alerte ; l'honnêteté vis-à-vis de soi-même et la circonspection, la volonté indéfectible face à la solitude ; le courage et l'ingéniosité face aux dangers extérieurs ; la compassion et le respect pour les autres habitants de la forêt. Ces qualités ont formé la culture originelle du Dhamma. -

Tilburg University Buddhist Psychology in the Workplace

Tilburg University Buddhist psychology in the workplace Marques, J.F.; Dhiman, S.K. Publication date: 2011 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Marques, J. F., & Dhiman, S. K. (2011). Buddhist psychology in the workplace: A relational perspective. Prismaprint. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. sep. 2021 Buddhist Psychology in the Workplace: A Relational Perspective Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnifi cus, prof. dr. Ph. Eijlander, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in zaal AZ 17 van de Universiteit LOW-RES PDF op maandag 7 november 2011 om 14.15 uur NOT PRINT-READYdoor Joan Francisca Marques geboren op 7 februari 1960 te Paramaribo, Suriname en om 15.15 uur door Satinder Kumar Dhiman geboren op 5 april 1957 te India Promotores: Prof. -

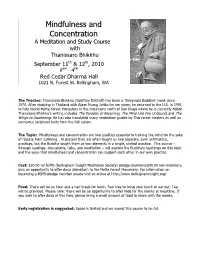

Mindfulness and Concentration a Meditation and Study Course with Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Mindfulness and Concentration A Meditation and Study Course with Thanissaro Bhikkhu September 11 th & 12 th , 2010 9AM - 4 PM Red Cedar Dharma Hall 1021 N. Forest St. Bellingham, WA The Teacher: Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff) has been a Theravada Buddhist monk since 1976. After studying in Thailand with Ajaan Fuang Jotiko for ten years, he returned to the U.S. in 1991 to help found Metta Forest Monastery in the mountains north of San Diego where he is currently Abbot. Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s writing includes The Paradox of Becoming, The Mind Like Fire Unbound , and The Wings to Awakening. He has also translated many meditation guides by Thai forest masters as well as numerous scriptural texts from the Pali canon. The Topic: Mindfulness and concentration are two qualities essential to training the mind for the sake of release from suffering. At present they are often taught as two separate, even antithetical, practices, but the Buddha taught them as two elements in a single, unified practice. This course – through readings, discussions, talks, and meditation – will explore the Buddha's teachings on this topic and the ways that mindfulness and concentration can support each other in our own practice. Cost: $30.00 for BIMS (Bellingham Insight Meditation Society) pledge-members/$40.00 non-members, plus an opportunity to offer dana (donation) to the Metta Forest Monastery. For information on becoming a BIMS-pledge member please visit us online at http://www.bellinghaminsight.org/ Food: There will be an hour and a half break for lunch. Feel free to bring your lunch or eat out. -

A Study of Physical Cleanliness Management in Theravāda Buddhism

A STUDY OF PHYSICAL CLEANLINESS MANAGEMENT IN THERAVĀDA BUDDHISM Ashin Sandimar A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 A Study of Physical Cleanliness Management in Theravāda Buddhism Ashin Sandimar A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2017 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalay University) 24 Thesis Title : A Study of Physical Cleanliness Management in Theravāda Buddhism Researcher : Ven. San Di Mar Degree : Master of Arts (Buddhist Studies) Thesis Supervisory Committee : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Adver tising), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Dr. Veerachart Nimanong, Pāḷi VI, B.A. (Buddhist Studies & Philosophy), M.A. (Philosophy), Ph.D. (Philosophy) Date of Graduation : March 14, 2018 Abstract This dissertation is entitled “A Study of Physical Cleanliness Management in Theravāda Buddhism.” 1) To study the concept of physical cleanliness in Theravada Buddhism.2) To analyze the Buddhist cleanliness management with the monastic life. 3) To apply the teachings on the Buddhist physical cleanliness management in the modern monastic Society. The results of the study indicate how the general concept of physical cleanliness correlates to other sources appearing in Buddhist texts; either in the Buddhist Canonical texts or in the other Buddhist texts. These were analyzed for a better understanding in a systematic and academic way. The research studies in detail how practitioners’ practice can be affected and provides an introduction to Theravāda Buddhist teachings. Those who follow the various practices associated with the Buddha’s teaching not only cultivated moral strength and selflessness, but also perform the highest service to their fellow human beings. -

AWARENESS ITSELF: the TEACHING of AJAAN FUANG JOTIKO Compiled and Translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey Degraff) Mind W

AWARENESS ITSELF: THE TEACHING OF AJAAN FUANG JOTIKO Compiled and Translated by Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff) Mind what you Say *** Normally, Ajaan Fuang was a man of few words who spoke in response to circumstances: If the circumstances warranted it, he could give long, detailed explanations. If not, he'd say only a word or two--or sometimes nothing at all. He held by Ajaan Lee's dictum: "If you're going to teach the Dhamma to people, but they're not intent on listening, or not ready for what you have to say, then no matter how fantastic the Dhamma you're trying to teach, it still counts as idle chatter, because it doesn't serve any purpose." *** I was constantly amazed at his willingness--sometimes eagerness--to teach meditation even when he was ill. He explained to me once, "If people are really intent on listening, I find that I'm intent on teaching, and no matter how much I have to say, it doesn't tire me out. In fact, I usually end up with more energy than when I started. But if they're not intent on listening, then I get worn out after the second or third word." *** "Before you say anything, ask yourself whether it's necessary or not. If it's not, don't say it. This is the first step in training the mind--for if you can't have any control over your mouth, how can you expect to have any control over your mind?" *** Sometimes his way of being kind was to be cross--although he had his own way of doing it. -

Lending Library

ITEM AUTHOR STATUS Mind of Clover: Essays in Zen Buddhist Ethics, The Aitken, Robert Available Women of Wisdom (Arkana) Allione, Tsultrim Available Freeing the Heart Dhamma Teachings from the Nuns Community at Amaravati & Amaro, Ajahn; Kovida, Sister; Roseborough, Jane; Surakomol, Cittaviveka Buddist Monasteries (Copy 1) Suliporn Available Freeing the Heart Dhamma Teachings from the Nuns Community at Amaravati & Amaro, Ajahn; Kovida, Sister; Roseborough, Jane; Surakomol, Cittaviveka Buddist Monasteries (Copy 2) Suliporn Available Buddha Armstrong, Karen Available Meditation and the Art of Dying Arya, Pandit Usharbudh, Ph.D. Available Awakening Joy: 10 Steps That Will Put You on the Road to Real Happiness (Copy 1) Baraz; James; Alexander; Shoshana Available Awakening Joy: 10 Steps That Will Put You on the Road to Real Happiness (Copy 2) Baraz; James; Alexander; Shoshana Available Path of Compassion: The Bodhisattva Precepts (Sacred Literature Series), The Batchelor, Martine Available Women in Korean Zen: Lives and Practices (Women and Gender in Religion) Batchelor, Martine Available Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening Batchelor, Stephen Available Confession of a Buddhist Atheist Batchelor, Stephen Available Living with the Devil: A Meditation on Good and Evil Batchelor, Stephen Available Verses from the Center: A Buddhist Vision of the Sublime (Copy 1) Batchelor, Stephen Available Verses from the Center: A Buddhist Vision of the Sublime (Copy 2) Batchelor, Stephen Available In the Himalayas: Journeys Through Nepal, -

Meditation Retreat With

Meditation retreat with Ajaan Thanissaro from 22 – 30 April 2017 Thanissaro Bhikkhu (Geoffrey DeGraff)–Ajaan Geoff for his students–is an American Buddhist monk of the Thai forest tradition. After graduating from Oberlin College in 1971 with a degree in European Intellectual History, he traveled to Thailand, where he studied meditation under Ajaan Fuang Jotiko, a student of the late Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo, one of the foremost teachers of the Thai forest tradition, and a student of its founder Ajaan Mun Bhuridatto. He ordained in 1976 and lived at Wat Dhammasathit, where he remained following his teacher's death in 1986. In 1991 he traveled to the hills of San Diego County, USA, where he helped Ajaan Suwat Suvaco establish Metta Forest Monastery. He was made abbot of the monastery in 1993. He has written numerous books: The Buddhist Monastic Code, Dhamma talks, Study Guides...He is also the translator of an anthology of the Pali Canon, together with a number of teachings from masters of the Thai forest tradition. All of his books are published on http://www.dhammatalks.org/index.html Ajaan Geoff came to France in 2011 at the invitation of Le Refuge. He then conducted a retreat which main theme was Self and Not-Self. And in 2015 on the theme “ Sati and Kamma” THEME OF THE RETREAT “ The five faculties ” The five faculties – conviction, persistence, mindfulness, concentration and discernment – are the qualities of the heart and mind that can be developed in meditation as well as in daily life, and lead to awakening. LOCATION Located in Haute Provence, Moustiers Sainte-Marie is titled Un Des Plus Beaux Village de France (one of The Most Beautiful Villages of France). -

Enseignements II

Les Livrets du Refuge Enseignements II Thanissaro Bhikkhu Textes Choisis n° 12 Enseignements II Les Livrets du Refuge sont disponibles au Centre Bouddhiste Le Refuge ainsi que dans certains monastères de la Tradition de la Forêt. Ils sont mis gracieusement à disposition sur le site : www.refugebouddhique.com Ils ne peuvent en aucun cas être utilisés à des fins commerciales. La distribution gratuite de ces livrets est rendue possible grâce à des dons individuels ou collectifs spécialement affectés à la publication des enseignements bouddhistes. La mise en page est de Jean-Yves Delarbre. © Les Éditions du Refuge Première édition - Juillet 2010 « Qu’une personne qui est observatrice vienne à moi, quelqu’un qui n’est pas faux, qui n’est pas fourbe, mais dont la nature est honnête. Je lui enseignerai le Dhamma. De sorte que, pratiquant selon les instructions, en peu de temps, il saura et verra par lui-même : « Ainsi, voilà comment il y a libération juste de l’esclavage, c’est-à-dire libération de l’ignorance. » MN 80 Avec notre gratitude pour Thanissaro Bhikkhu, qui a autorisé les Éditions du Refuge à traduire et publier ces enseignements. « Le Don du Dhamma surpasse tout autre Don. » Dhammapada 354 Nos remerciements vont aux personnes dont la générosité a permis la publication de ces enseignements. Kingdao Bellair, Thida Boontharm, Myriam Bourgeois, Lionel, Philippe et Watanee Cortey-Dumont, Nicha Dab-Ngoen, Aure Laviolette, Nasaran Leesirisern, Ananda, Chandhana et Claude Le Ninan, Sébastien Leroy, Sudarat Sereewat, Phairin Siri-angoon, Vipasie Smithiphong, Phasinee Sornhiran. La générosité est la première des dix perfections. -

Thinking Like a Thief.Pdf

Thinking like a Thief Thanissaro Bhikkhu In Theravada, the relationship between teacher and student is like that between a master craftsman and his apprentice. The Dharma is a skill, like carpentry, archery, or cooking. The duty of the teacher is to pass on the skill not only by word and example, but also by creating situations to foster the ingenuity and powers of observation the student will need in order to become skillful. The duty of the student is to choose a reliable master—someone whose skills are solid and whose intentions can be trusted—and to be as observant as possible. After all, there’s no way you can become a skilled craftsman by passively watching the master or merely obeying his words. You can’t abdicate responsibility for your own actions. You have to pay attention both to your actions and to their results, at the same time using your ingenuity and discernment to correct mistakes and overcome obstacles as they arise. This requires that you combine respect for your teacher with respect for the principle of cause and effect as it plays out in your own thoughts, words, and deeds. Shortly before my ordination, my teacher—Ajaan Fuang Jotiko—told me: “If you want to learn, you’ll have to think like a thief and figure out how to steal your knowledge.” And soon I learned what he meant. During my first years with him, he had no one to attend to his needs: cleaning his hut, boiling the water for his bath, looking after him when he was sick, etc.