Postmodern and Christian Expressions in the Matrix Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems Via Virtualization

Enter the Matrix: Safely Interruptible Autonomous Systems via Virtualization Mark O. Riedl Brent Harrison School of Interactive Computing Department of Computer Science Georgia Institute of Technology University of Kentucky [email protected] [email protected] Abstract • An autonomous system may have imperfect sensors and perceive the world incorrectly, causing it to perform the Autonomous systems that operate around humans will wrong behavior. likely always rely on kill switches that stop their exe- cution and allow them to be remote-controlled for the • An autonomous system may have imperfect actuators and safety of humans or to prevent damage to the system. It thus fail to achieve the intended effects even when it has is theoretically possible for an autonomous system with chosen the correct behavior. sufficient sensor and effector capability that learn on- • An autonomous system may be trained online meaning line using reinforcement learning to discover that the kill switch deprives it of long-term reward and thus it is learning as it is attempting to perform a task. Since learn to disable the switch or otherwise prevent a hu- learning will be incomplete, it may try to explore state- man operator from using the switch. This is referred to action spaces that result in dangerous situations. as the big red button problem. We present a technique Kill switches provide human operators with the final author- that prevents a reinforcement learning agent from learn- ing to disable the kill switch. We introduce an interrup- ity to interrupt an autonomous system and remote-control it tion process in which the agent’s sensors and effectors to safety. -

The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media LabCom Books 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-090-6 Título: The Anime Galaxy Autor: Herlander Elias Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice ABSTRACT & KEYWORDS3 INTRODUCTION5 Objectives............................... 15 Research Methodologies....................... 17 Materials............................... 18 Most Relevant Artworks....................... 19 Research Hypothesis......................... 26 Expected Results........................... 26 Theoretical Background........................ 27 Authors and Concepts...................... 27 Topics.............................. 39 Common Approaches...................... 41 1 FROM LITERARY TO CINEMATIC 45 1.1 MANGA COMICS....................... 52 1.1.1 Origin.......................... 52 1.1.2 Visual Style....................... 57 1.1.3 The Manga Reader................... 61 1.2 ANIME FILM.......................... 65 1.2.1 The History of Anime................. 65 1.2.2 Technique and Aesthetic................ 69 1.2.3 Anime Viewers..................... 75 1.3 DIGITAL MANGA....................... 82 1.3.1 Participation, Subjectivity And Transport....... 82 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: The Manga And Anime Con- vergence........................ 86 1.4 ANIME VIDEOGAMES.................... 90 1.4.1 Prolongament...................... 90 1.4.2 An Audience of Control................ 104 1.4.3 The Videogame-Film Symbiosis............ 106 1.5 COMMERCIALS AND VIDEOCLIPS............ 111 1.5.1 Advertisements Reconfigured............. 111 1.5.2 Anime Music Video And MTV Asia......... -

Believing in Fiction I

Believing in Fiction i The Rise of Hyper-Real Religion “What is real? How do you define real?” – Morpheus, in The Matrix “Television is reality, and reality is less than television.” - Dr. Brian O’Blivion, in Videodrome by Ian ‘Cat’ Vincent ver since the advent of modern mass communication and the resulting wide dissemination of popular culture, the nature and practice of religious belief has undergone a Econsiderable shift. Especially over the last fifty years, there has been an increasing tendency for pop culture to directly figure into the manifestation of belief: the older religious faiths have either had to partly embrace, or strenuously oppose, the deepening influence of books, comics, cinema, television and pop music. And, beyond this, new religious beliefs have arisen that happily partake of these media 94 DARKLORE Vol. 8 Believing in Fiction 95 – even to the point of entire belief systems arising that make no claim emphasises this particularly in his essay Simulacra and Simulation.6 to any historical origin. Here, he draws a distinction between Simulation – copies of an There are new gods in the world – and and they are being born imitation or symbol of something which actually exists – and from pure fiction. Simulacra – copies of something that either no longer has a physical- This is something that – as a lifelong fanboy of the science fiction, world equivalent, or never existed in the first place. His view was fantasy and horror genres and an exponent of a often pop-culture- that modern society is increasingly emphasising, or even completely derived occultism for nearly as long – is no shock to me. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

Document 273 5-5-2014 – Download

Case 2:07-cv-00552-DB-EJF Document 273 Filed 05/05/14 Page 1 of 46 PROSE 1 SOPHIA STEWART P.O. BOX 31725 2 Las Vegasl NV 89173 3 702-501-5900 (PH) 4 ... IN PROPRIA PERSONA v: ---;;:\-CQ\( 5 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT \l~YU I I "' 6 FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH 7 SOPHIA STEWART, HON. EVELYN J. FURSE 8 Plaintiff, v. HON. DEE BENSON 9 MICHAEL STOLLER, GARY BROWN, Case No.: 2:07CV552 DB-EJF 10 DEAN WEBB, AND JONATHAN 11 LUBELL OBJECTION TO COURT DENIAL Defendants. TO AWARD DAMAGES AGAINST 12 DEFENDANT LUBELL AND 13 DEMAND FOR EXPEDITED AWARD 14 15 16 COMES NOW1 PLAINTIFF SOPHIA STEWART1 bringing forth the Objection To the 17 Court's Denial To Award Damages Against All Defendants And Demand For 18 Expedited Award of Damages in the amount of One Billion Three Hundred and 19 Sixty Seven Million $1,367,000,000.00 dollars for The Matrix Trilogy damages and 20 Three point five Billion $3,580,000,000.00 dollars in damages for the Terminator 21 Franchise Series. 22 23 Plaintiff brings forth this objection against the court for violating the 24 Plaintiff's constitutional Sixth and fourth amendments "Due Process and Equal 25 Protection" rights and obstructing her from a jury trial and the ability to face the 26 defendants in court for more than 6 years while Jonathan Lubell was deceased, 27 thus constituting a violation of racial discrimination and fraud. Racial 28 discrimination by concerted action is a federal offense under 18 U.S.C. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

To Film Sound Maps: the Evolution of Live Tone’S Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-Ho

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Nottingham From ‘Screenwriting for Sound’ to Film Sound Maps: The Evolution of Live Tone’s Creative Alliance with Bong Joon-ho Nikki J. Y. Lee and Julian Stringer Abstract: In his article ‘Screenwriting for Sound’, Randy Thom makes a persuasive case that sound designers should be involved in film production ‘as early as the screenplay…early participation of sound can make a big difference’. Drawing on a critically neglected yet internationally significant example of a creative alliance between a director and post- production team, this article demonstrates that early participation happens in innovative ways in today’s globally competitive South Korean film industry. This key argument is presented through close analysis of the ongoing collaboration between Live Tone - the leading audio postproduction studio in South Korea – and internationally acclaimed director Bong Joon-ho, who has worked with the company on all six of his feature films to date. Their creative alliance has recently ventured into new and ambitious territory as audio studio and director have risen to the challenge of designing the sound for the two biggest films in Korean movie history, Snowpiercer and Okja. Both of these large-scale multi-language movies were planned at the screenplay stage via coordinated use of Live Tone’s singular development of ‘film sound maps’. It is this close and efficient interaction between audio company and client that has helped Bong and Live Tone bring to maturity their plans for the two films’ highly challenging soundscapes. -

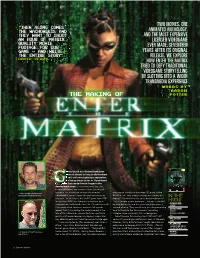

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Download Films / Movies Card Game (PDF)

Back to the Future Blade Runner ET 1985 / sci-fi 1982 / sci-fi 1982 / sci-fi Robert Zemeckis (director) Ridley Scott (director) Steven Spielberg (director) Michael J Fox Harrison Ford Dee Wallace Christopher Lloyd The Godfather Harry Potter and the The Exorcist 1972 / crime thriller Philosopher's Stone 1973 / horror Francis Ford Coppola (director) 2001 / fantasy William Friedkin (director) Maron Brando Chris Columbus (director) Ellen Burstyn Al Pacino Daniel Radcliffe Jaws Raiders of the Lost Ark Goldfinger 1975 / thriller 1981 / action / adventure 1964 / spy thriller Steven Spielberg (director) Steven Spielberg (director) Guy Hamilton (director) Roy Scheider Harrison Ford Sean Connery Robert Shaw Jurassic Park Mad Max The Lion King 1993 / sci-fi 1979 / action 1994 / cartoon / musical Steven Spielberg (director) George Miller (director) Roger Allers / Rob Minkoff Sam Neill Mel Gibson (directors) Laura Dern Joanne Samuel Mission Impossible Pirates of the Caribbean: 1996 / spy / action Pinocchio Dead Man's Chest Brian De Palma (director) 1940 2006 / fantasy adventure Tom Cruise cartoon / musical / fantasy Gore Verbinski (director) Paula Wagner Johnny Depp Apocalypse Now Schindler's List The Matrix 1979 / war film 1993 / historical drama 1999 / sci-fi / action Francis Ford Coppola (director) Steven Spielberg (director) The Wachowskis (directors) Marlon Brando Liam Neeson Keanu Reeves Martin Sheen Ralph Fiennes Carrie-Anne Moss Titanic Crazy Rich Asians The Lord of the Rings: The 1997 / disaster / romance 2018 / romantic comedy Fellowship of the Ring James Cameron (director) Jon M. Chu (director) 2001 / fantasy / adventure Leonardo DiCaprio Constance Wu Peter Jackson (director) Kate Winslet Gemma Chan Elijah Wood Ian McKellen Toy Story The Sound of Music The Dark Knight 1995 1965 / musical / drama 2008 / superhero computer-animated comedy Robert Wise (director) Christopher Nolan (director) John Lasseter (director) Julie Andrews Christian Bale Tom Hanks (voice) Christopher Plummer Michael Caine © ELTbase.com 2019. -

Bruno Mölder

ISSN 0234-8160 wmm KOIK ON KOKKU ... MATRIX? Bruno Mölder: Kas me oleme ajud purgis? Tanel Tammet: Kas me märkaksime endast targemat arvutitsivilisatsiooni? Jüri Eintalu: Kas filosoofia teab, mis homne toob? Slavoj Zižek: Meie tegelik passiivsus versus virtuaalne kõikvõimsus. Unenäod ja luupainajad Mehis Heinsaare ja Matt Barkeri novellides. Arvustuse all on Andres Herkeli, Aare Pilve ja Kadri Tüüri mõttemasinad. Katrin Kivimaa: maalikunstnik Alice Kask. Piret Bristoli ja Kirsti Oidekivi luulet. • Eesti Kirjanike Liidu ajakiri. Ilmub alates 1986. a. juulist. 18. aastakäik. September, 2003 Nr. 9. SISUKORD Robert Graves Läbi luupainaja 1 Slavoj Žižek Matrix: perversiooni kaks kulge 66 Mehis Heinsaar Vennad uneluses 2 Jüri Eintalu Matrix: filosoofial juhtmed Matt Barker Malmkurat 16 seinast väljät 87 Piret Bristol Luulet 29 Bruno Mölder Matrix purgis 95 Kirsti Oidekivi Luulet 34 Tansl Tammet Matrix, skynet ja sõda Jaak Rand Harilik pealkiri 39 teispoolsusega 106 Mart Kangur Jaak Rand 47 Eksinud... 49 Lotmanieux 53 Vaatenurk Ulo Mattheuis Mõttemasinaga sakraalajas 111 Katrin Kivimaa Meesaktid lõuendil j& Jaanus Adamson Ideaal ja iha 117 vineeril: Alice Kase viimaste maalide Märt Väljataga Subjektiga vastu tõlgendamise projekt 64 ideoloogiamüüri 125 Kujundus: Jüri Kaarma © "Vikerkaar", Fotod Alice Katse maalidest: Toomas Kohv 2003. Esikaanel: ALICE KASK. Kükitav Tagakaanel: ALICE KASK. Näoga mees. Oli, lõuend. 145x210 cm. 20Q2. mees. Õli, lõuend. 145x210 cm. 2003. ROBERT GRAVES Läbi luupainaja Inglise keelest tõlkinud Märt Väljatagu Ärgu sind kunagi lakaku lummamast Koht, kuhu sa ennast mõnikord unistad, Kaugel kõikidest unenägudest, Ega ka need, keda leiad sealt eest, kuigi harva Võid nende seltsi sa istet võtta - Nood taltsutamatud, elavad, õrnad. Kas pole sa kohanud neid? Keda? Nad aja On mähkinud nagu jõe ümber oma maja, Nii et ajaloo teed mööda sinna ei pääse Neid loendama või nimetama.