Resource Ownership in Drinking Water Production. Comparing Public and Private Operators' Strategies in Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Ordre Du Jour Actualisé

Conseil provincial Palais provincial Place Saint-Lambert, 18A 4000 LIEGE N° d'entreprise : 0207.725.104 PROCÈS-VERBAL DE LA RÉUNION PUBLIQUE DU 30 JANVIER 2020 M. Jean-Claude JADOT, Président, ouvre la séance à 16h30’. M. Irwin GUCKEL et Mme Anne THANS-DEBRUGE siègent au Bureau en qualité de Secrétaires. Mme la Directrice générale provinciale assiste à la séance. Il est constaté par la liste de présence que 49 membres assistent à la séance. Présents : Mme Myriam ABAD-PERICK (PS), M. Mustafa BAGCI (PS), Mme Astrid BASTIN (CDH-CSP), Mme Muriel BRODURE-WILLAIN (PS), M. Serge CAPPA (PS), M. Thomas CIALONE (MR), Mme Deborah COLOMBINI (PS), Mme Catharina CRAEN (PTB), Mme Virginie DEFRANG-FIRKET (MR), M. Maxime DEGEY (MR), M. Marc DELREZ (PTB), M. André DENIS (MR), M. Guy DUBOIS (MR), M. Hajib EL HAJJAJI (ECOLO), M. Miguel FERNANDEZ (PS), Mme Katty FIRQUET (MR), Mme Nathalie FRANÇOIS (ECOLO), Mme Murielle FRENAY (ECOLO), M. Luc GILLARD (PS), Mme Isabelle GRAINDORGE (PS), M. Irwin GUCKEL (PS), M. Pol HARTOG (MR), Mme Catherine HAUREGARD (ECOLO), M. Alexis HOUSIAUX (PS), M. Jean-Claude JADOT (MR), Mme Catherine LACOMBLE (PTB), Mme Caroline LEBEAU (ECOLO), M. Luc LEJEUNE (CDH-CSP), M. Eric LOMBA (PS), Mme Valérie LUX (MR), M. Marc MAGNERY (ECOLO), Mme Nicole MARÉCHAL (ECOLO), M. Robert MEUREAU (PS), M. Jean-Claude MEURENS (MR), Mme Marie MONVILLE (CDH-CSP), Mme Assia MOUKKAS (ECOLO), M. Daniel MÜLLER (PFF-MR), Mme Sabine NANDRIN (MR), M. Luc NAVET (PTB), Mme Chantal NEVEN-JACOB (MR), M. Didier NYSSEN (PS), M. Alfred OSSEMANN (SP), M. Rafik RASSAA (PTB), Mme Isabelle SAMEDI (ECOLO), Mme Marie-Christine SCHEEN (PTB), M. -

SEANCE DU CONSEIL COMMUNAL EN DATE DU 2O JUIN 2013 Présents

SEANCE DU CONSEIL COMMUNAL EN DATE DU 2O JUIN 2013 Présents : Mme I. SIMONIS, Bourgmestre; Mme S. THEMONT, MM F. PAVONE, L. LÉONARD, V. POLÈSE et M. D’JOOS; Échevins; MM. J-J. VERVAEREN, Y. MOULIN, J. DISTER, Mme M. MANTANUS, M. A. HOURLAY, Mmes N. BLONDIAUX, J. WINTGENS, MM. J-D. LEJEUNE, F. VANDELLI, D. COPELLI, Mme V. PASSANI, MM. M. CLAESSENS, H. GODELAINE, A. HAMIDOVIC, Mme F. DANTINE, M. A. GODIN, Mme V. COMELLI, M. J. RIGO, Mme J. VEZZARO, MM. D. PERRIN et S. ANCIA, Conseillers communaux; Mr P. VRYENS, Secrétaire communal. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ M. R. FLAGOTHIER, Conseiller communal, absent, est excusé. Mme C. MEGALI, Présidente du CPAS, entre en séance avant le 2 ème objet. M. Y. MOULIN, Conseiller communal, quitte la séance avant le 38 ème objet. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ La séance est ouverte à 19 h 30 sous la présidence de Madame SIMONIS. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ SEANCE PUBLIQUE 1er OBJET : COMPTES ANNUELS POUR 2012 DU C.P.A.S. – APPROBATION . LE CONSEIL, Vu la loi du 8 juillet 1976 organique des Centres Publics d’Action Sociale telle que modifiée, et spécialement son article 89; Vu l’Arrêté du Gouvernement wallon du 5 juillet 2007 portant le règlement général de la comptabilité communale en exécution de l’article L1315-1 du Code de la démocratie locale et de la décentralisation; Vu l’arrêté du Gouvernement wallon du 17 janvier 2008 adaptant le règlement général de la comptabilité communale aux Centres Publics d’Action Sociale; Vu la circulaire en date du 20 juin 2008 (n° 5164) de Monsieur le Ministre des Affaires intérieures et de la Fonction publique; Vu le Code de la démocratie locale et de la décentralisation; Vu le procès-verbal de la réunion du Comité de concertation Commune/C.P.A.S. -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

Belgium-Luxembourg-6-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges & Antwerp & Western Flanders Eastern Flanders p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Western Wallonia p182 The Ardennes p203 Luxembourg p242 #_ THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Helena Smith, Andy Symington, Donna Wheeler PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Belgium BRUSSELS . 34 Antwerp to Ghent . 164 & Luxembourg . 4 Around Brussels . 81 Westmalle . 164 Belgium South of Brussels . 81 Hoogstraten . 164 & Luxembourg Map . 6 Southwest of Brussels . 82 Turnhout . 164 Belgium North of Brussels . 82 Lier . 166 & Luxembourg’s Top 15 . 8 Mechelen . 168 Need to Know . 16 BRUGES & WESTERN Leuven . 173 First Time . 18 FLANDERS . 83 Leuven to Hasselt . 177 Hasselt & Around . 178 If You Like . 20 Bruges (Brugge) . 85 Tienen . 178 Damme . 105 Month by Month . 22 Hoegaarden . 179 The Coast . 106 Zoutleeuw . 179 Itineraries . 26 Knokke-Heist . 107 Sint-Truiden . 180 Travel with Children . 29 Het Zwin . 107 Tongeren . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 De Haan . 107 Zeebrugge . 108 Lissewege . 108 WESTERN Ostend (Oostende) . 108 WALLONIA . 182 MATT MUNRO /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY MUNRO MATT Nieuwpoort . 114 Tournai . 183 Oostduinkerke . 114 Pipaix . 188 St-Idesbald . 115 Aubechies . 189 De Panne & Adinkerke . 115 Belœil . 189 Veurne . 115 Lessines . 190 Diksmuide . 117 Enghien . 190 Beer Country . 117 Mons . 190 Westvleteren . 117 Waterloo Battlefield . 194 Woesten . 117 Nivelles . 196 Watou . 117 Louvain-la-Neuve . 197 CHOCOLATE LINE, BRUGES P103 Poperinge . 118 Villers-la-Ville . 197 Ypres (Ieper) . 119 Charleroi . 198 Ypres Salient . 123 Thuin . 199 HELEN CATHCART /LONELY PLANET © PLANET /LONELY HELEN CATHCART Comines . 124 Aulne . 199 Kortrijk . 125 Ragnies . 199 Oudenaarde . -

Le Mini Echos De Modave

Echos de Modave Commune de Modave Septembre 2015 / n° 41 Chers citoyens, Intradel et votre commune vous invitent à donner une seconde vie aux objets dont vous ne vous servez plus ! Avec le soutien de la Région Wallonne et de la Province de Liège, nous mettons à disposition cette nouvelle structure : votre "Give-Box" ou "Boîte à donner". Cette give-box est un lieu de libres-échanges : DONNER et PRENDRE gratuitement! Elle sera installée, dès la mi-octobre, dans le couloir de l’administration communale et nous vous invitons à venir y jeter un œil. Comment ça marche ? 1. Chacun peut donner un objet dont il n'a plus besoin, en bon état de fonctionnement, pour en faire don au lieu de le jeter. 2. Chacun peut prendre, gratuitement et sans obligation de donner en échange. La give-box contribuera à leur donner une deuxième vie, en faisant plaisir, dans une volonté de consommer durablement et différemment. Faire vivre la give-box, c'est refuser la surconsommation et favoriser l'économie collaborative. Que dépose-t-on ? Les objets en bon état et devenus inutiles pour vous : les jeux des enfants qui ont grandi, les vêtements que vous ne mettez plus, vos livres déjà lus, votre ancienne vaisselle... L’Accueil Temps Libre de Modave (ATL), le CCCA de Modave et le Plan de Cohésion Sociale (PCS) vous proposent : Un Atelier ... Intergénérationnel Vous habitez Modave ? Vous avez un mercredi après-midi de libre par mois ? Vous avez envie de transmettre une passion, une expérience, une activité (cuisine, tricot, musique, bricolage, lecture, promenade,…) à des enfants ? Les enfants de l’Accueil Temps Libre de l’école communale de Modave vous attendent lors des activités du mercredi après-midi de 14h à 17h à raison d’une fois par mois !! Venez y partager vos compétences et vivons ensemble un moment d’échange inoubliable. -

Liste Triee Par Noms

04/03/2020 LISTE TRIEE PAR NOMS LISTE TRIEE PAR NOMS Nom de famille Prénom Adresse N° Code postal Commune ABATE EKOLLO Joëlle de Zoum Rue Naniot 277 4000 LIEGE ABATI Angelo Rue Dos Fanchon 37-39 4020 LIEGE ABAYO Jean-Pascal Montagne Saint-Walburge 167 4000 LIEGE ABBATE Danielo Rue du Petit Chêne 2 4000 LIEGE ABBATE Damien Rue du Petit Chêne 2 4000 LIEGE ABCHAR Tarek Avenue Emile Digneffe 2 4000 LIEGE ABDELEMAM ABDELAZIZ Ahmed Farid Lisdaran Cavan 2R212 2 R212 Irlande ABOUD Imad Bd de Douai 109 4030 LIEGE ABRAHAM Françoise Rue de Hesbaye 75 4000 LIEGE ABRASSART Charles Avenue Grégoire 36 4500 HUY ABSIL Gilles Rue de la Mardelle, Heinsch 6 6700 ARLON ABSIL Gabriel Grand'Rue 45 4845 SART-LEZ-SPA ABU SERIEH Rami Rue Devant Les Religieuses 2 4960 Malmedy ACAR Ayse Rue Peltzer de Clermont 73 4800 VERVIERS ACHARD Julie Quai de COmpiègne 52 4500 HUY ACIK Mehtap Rue Fond Pirette 3B 4000 LIEGE ACKAERT Alain Rue du Long Thier 50/SS 4500 HUY ADAM Aurélie Boulevard du 12ième de Ligne 1 4000 LIEGE ADAM Christelle Rue Pré de la Haye 6 4680 OUPEYE 1/301 LISTE TRIEE PAR NOMS Nom de famille Prénom Adresse N° Code postal Commune ADAM Laurence Avenue de la Closeraie 2-16 4000 LIEGE (ROCOURT) ADAM Stéphanie Rue Professeur Mahaim 84 4000 LIEGE ADAM Youri Biche Les Prés 12 4870 TROOZ ADANT Jean-Philippe Rue Aux Houx 41 D 4480 CLERMONT-SOUS-HUY ADANT Jean-François Rue Provinciale 499 4458 FEXHE-SLINS ADASY ALMOUKID Marc Avenue Martin Luther King 2 87042 LIMOGES ADEDJOUMO Moïbi Rue du Parc 29 4800 VERVIERS ADJAMAGBO Hubert ADLJU Arsalan Rue des déportés 3 4840 -

Le Mini Echos De Modave

Echos de Modave Commune de Modave Avril 2017 / n°56 DU 1 AU 31 MAI Points de collecte sur la commune : Administration communale PLACE G. HUBIN 1-3 4577 VIERSET Chacune des implantations scolaires communales, libres et CTA Proxy Delhaize ROUTE DE STRÉE 26 4577 STRÉE Sodemat - Duchêne ROUTE DE STRÉE 44 4577 MODAVE Vivaqua Modave CHAUSSEE DE PAILHE 3 4577 MODAVE Zone de police du Condroz RUE DU BOIS ROSINE 16 4577 STREE-LEZ-HUY Portes ouvertes à l’école communale, le samedi 6 mai de 10h à 15h30 Accueil par les enseignants qui répondront à toutes vos questions. La directrice sera présente dans les 3 implantations aux heures suivantes : Les Gottes : de 10h à 11h30 - Modave : de 12h à 13h30 - Vierset : de 14h à 15h30 TROPHÉE SPORTIF A l’occasion de la Journée Retrouvailles, le dimanche 27 août 2017, la commune de Modave remettra des trophées sportifs pour récompenser des performances sportives remarquables. Toutes les disciplines sont mises sur le plan d’égalité, qu’elles soient exercées par des amateurs ou des professionnels. 2 trophées sportifs seront attribués : l’un à un sportif individuel et l’autre à une équipe ou un groupement. Les candidats doivent être domiciliés à Modave ou affiliés à un groupement modavien, c’est-à-dire ayant son siège ou exercer son activité sportive sur le territoire de la commune de Modave. La présentation des candidatures est faite par écrit à l’Administration communale, Commission « Trophée sportif », Place Georges Hubin à 4577 Vierset-Barse, avant le 30 juin 2017. Ces candidatures seront accompagnées des éléments motivant la demande. -

Plan De Mobilité Des Communes D'engis, Huy

FICHE PROJET PLAN DE MOBILITÉ DES COMMUNES d’engis, huy, marchin, modave, villers-le-bouillet et wanze Elaboration d’un plan intercommunal de mobilité Situées à l’ouest de la Province de Liège, SUR 6 COMMUNES DE LA PROVINCE DE LIÈGE les communes d’Engis, Huy, Marchin, Modave, Villers-le-Bouillet et Wanze se trouvent à mi-distance entre Liège et Maître d’ouvrage Service Public de Wallonie Namur. Personne de contact Michèle LORGE - +32 (0)81 77 31 18 [email protected] Les enjeux de ce PICM: Etude 2011 - 2014 • Une synchronisation des documents Budget étude 188.305,04 € TVAC de planification et du plan de mobilité Partenaire Agora vu que l’état d’avancement des documents de planification diffèrent d’une commune à l’autre. • Les connexions entre Engis et les pôles que sont Wanze et Huy. • Un réseau automobile à hiérarchiser et sécuriser. Un sentiment d’insécurité est omniprésent dans les villages, aux abords des écoles et le long des axes de circulation. Il en ressort un besoin évident d’aménagements et de maîtrise des vitesses • La desserte des zones d’activités et des grandes entreprises du territoire • La présence de nombreuses entreprises sur le territoire, notamment le long de La Meuse et des voies ferrées implique que cette thématique est un enjeu important • La gestion du stationnement sur le centre de Huy • Des villages et hameaux à desservir par des modes alternatifs à la voiture individuelle, notamment par le développement de la pratique du covoiturage • Des modes doux à valoriser et développer sur un territoire comprenant de nombreux RAVeL’s La mobilité est donc un enjeu majeur pour la qualité de vie et le dynamisme de ces commune et elles ont de ce fait décidé de se doter d’un Plan InterCommunal de Mobilité (PCM) afin d’être outillée d’un document d’actions pour les 10 ans à venir. -

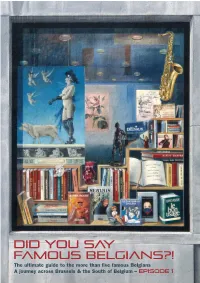

The Ultimate Guide to the More Than Five Famous Belgians a Journey

The ultimate guide to the more than five famous Belgians A journey across Brussels & the South of Belgium – Episode 1 Rue St André, Brussels © Jeanmart.eu/belgiumtheplaceto.be When a Belgian arrives in the UK for the delighted to complete in the near future first time, he or she does not necessarily (hence Episode I in the title). We Belgians expect the usual reaction of the British when are a colourful, slightly surreal people. they realise they are dealing with a Belgian: We invented a literary genre (the Belgian “You’re Belgian? Really?... Ha! Can you name strip cartoon) whose heroes are brilliant more than five famous Belgians?.” When we ambassadors of our vivid imaginations and then start enthusiastically listing some of of who we really are. So, with this Episode 1 our favourite national icons, we are again of Did you say Famous Belgians!? and, by surprised by the disbelieving looks on the presenting our national icons in the context faces of our new British friends.... and we of the places they are from, or that better usually end up being invited to the next illustrate their achievements, we hope to game of Trivial Pursuit they play with their arouse your curiosity about one of Belgium’s friends and relatives! greatest assets – apart, of course, from our beautiful unspoilt countryside and towns, We have decided to develop from what riveting lifestyle, great events, delicious food appears to be a very British joke a means and drink, and world-famous chocolate and of introducing you to our lovely homeland. beer - : our people! We hope that the booklet Belgium can boast not only really fascinating will help you to become the ultimate well- famous characters, but also genius inventors informed visitor, since.. -

Académie Provinciale Des Sports

Académie provinciale des Sports Essaie sports pour euros diteur responsable : Province de Liège, Place Saint Lambert Place 18A, 4000 Liège de Liège, : Province responsable diteur Retrouvez la séquence radio «Académie provinciale des Sports» le é mardi vers 15h45 dans Liège Aller-Retour sur Vivacité 90.05 FM ▪ Parrainée par Charline Van Snick et Lionel Cox, médaillés olympiques à «Londres 2012» CONTACT ET INFORMATIONS : Infos : 04/237.91.58 - www.provincedeliege.be/sports - [email protected] Tel : 04/237.91.58 Email : [email protected] Une initiative du Service des Sports de la Province de Liège en partenariat avec : Site: www.provincedeliege.be/sports Sports proposés pour les 4 à 7 ans Activités corporelles et motrices de base : Psychomotricité et accoutumance à l’eau (option possible Baby poney et Judo) (30€ pour les 24 séances) LES OBJECTIFS • Rendre le goût du sport aux enfants en découvrant les disciplines de manière ludique et sans esprit de compétition. Sports proposés pour les 6 à 11 ans • Donner la possibilité aux enfants de 4 à 11 ans de s’essayer à différents sports et pourquoi pas de trouver leur voie. • Constituer un tremplin entre le sport abordé de manière très générale à Ateliers de découverte ludique et/ou de progression dans l’école et le sport spécialisé dans les clubs et fédérations. les sports suivants : • Eviter le décrochage sportif en évoluant au rythme de l’enfant. Equitation · athlétisme · escrime · unihockey ou hockey · mini tennis, tennis · prénatation et natation · judo · éveil sports 3 Sports ballons orienté vers le handball et le basket-ball · golf · danse · LES IMPLANTATIONS pour 30 € gymnastique · tennis de table · karaté · escalade · vélo · mini 9 Bassins volley-ball · hockey sur gazon · capoeira · badminton · aïkido · nage synchronisée · kindball · rugby · Hip Hop · Zumba, .. -

La Province De Liège Soutient La Formation Des Jeunes

L’Académie provinciale des Sports • LIEGE NORD La Province de Liège soutient la formation LES OBJECTIFS des jeunes • Répondre aux besoins des enfants en proposant des initiations sportives, ludiques et éducatives. • Favoriser l’épanouissement et l’éducation sportive grâce à une pédagogie Académie provinciale des Sports - ANS adaptée à chaque catégorie d’âge (4-6 ans et 6-11 ans) et à chaque enfant. • Assurer l’encadrement des séances par des moniteurs qualifiés. • Permettre aux enfants d’affirmer leurs goûts pour les activités sportives et éventuellement, par la suite, d’intégrer un club sportif local. LES IMPLANTATIONS : 9 BASSINS Condroz (Nandrin, Tinlot, Neupré, Marchin, Modave,...) Haute-Meuse (Flémalle, Engis, Grâce-Hollogne, St-Nicolas, Jemeppe, Ans,...) Hesbaye Nord (Waremme, Lincent, Hannut, Verlaine,...) Retrouvez la séquence radio «Académie provinciale des Sports» le Liège Nord (Herstal, Juprelle, Oupeye,...) mardi vers 15h45 dans Liège Aller-Retour sur Vivacité 90.5 FM Liège Sud (Fléron, Beyne-Heusay, Soumagne,...) Meuse-Hesbaye (Wanze, Huy, Villers-le-Bouillet, Burdinne, Verlaine,...) Ourthe (Esneux, Comblain, Ferrières, Anthisnes, Sprimont...) Verviers (Verviers, Pepinster, Dison, Limbourg,...) Warche-Amblève (Malmedy, Stavelot,...) Chaque activité est pratiquée durant 8 séances et poursuivra le développement Rejoignez-nous aussi sur notre Page Facebook des qualités décrit dans l’éveil sportif. Académie des Sports-Province de Liège L’année scolaire est divisée en 3 modules de 8 séances sportives : • d’octobre à décembre • de janvier à mars Saint Lambert Place A, Liège de Liège, : Province responsable éditeur • d’avril à juin Possibilité d’INTEGRATION D’ENFANTS DE 4 A 11 ANS souffrant d’un handicap au Académie provinciale des Sports - Liège Nord sein de l’Académie des Sports !!! INFOS GÉNÉRALES : Le volet « Handisport » propose des activités sportives adaptées pour les enfants Tel : 04/237.91.58 Une initiative du Service des Sports de la Province de Liège et personnes moins valides. -

Huy-Waremme, Un Territoire Attractif Pour Les Entreprises

Huy-Waremme, un territoire attractif pour les entreprises Parc d’activités économiques de Villers-le-Bouillet/Wanze Espace Entreprises de Tihange (Huy) Ilot d’entreprises de Strée (Modave) La SPI sur Huy-waremme, c’est : • 472 entreprises • 7.060 emplois • 12 parcs d’activités économiques (616 ha) occupés à 80,4 % • 10 bâtiments pour entreprises Bâtiment Relais de Héron/Couthuin (Héron) Parc d’activités économiques d’Hermalle-sous-Huy (Engis) agence de développement pour la province de Liège Atrium VERTBOIS l 11 Rue du Vertbois l B-4000 LIEGE l T. +32 (0)4 230 11 11 l F. +32 (0)4 230 11 20 www.spi.be Quel espace économique pour votre activité ? Les parcs d’activités économiques (aussi appelés zonings) (*) • Industriel, pour les activités liées à un processus de transformation de matières premières ou semifinies, de conditionnement, de stockage, de logistique ou de distribution. • Mixte, pour les activités d’artisanat, de service, de distribution, de recherche ou les petites industries. Halls et installations de stockage y sont admis. • Avec surimpression (réservant l’accès à certaines activités). Les Bâtiments Relais Mis à disposition pour une durée limitée, ces halls relais comprennent une partie atelier et une partie bureau. Les Espaces Entreprises Mis à disposition pour une durée limitée, ces centres d’affaires proposent bureaux (parfois aussi ateliers) et services communs (salle de réunion, cuisine, parking, …). (*) Définitions issues du CODT Wallon (Code du Développement territorial) Plusieurs formules d’implantation dont l’emphytéose. Achat, emphytéose, location, mise à disposition ? L’achat d’un terrain ou la location d’un bâtiment sont des actes assez classiques.