Electrophysiology Read-Out Tools for Brain-On-Chip Biotechnology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First Name Surname

To find your name, click 'ctrl' + 'F' and type your surname. If you entered after 20/02/20 you will not appear on this list, an updated version will be put online on or around the 28/02/20. Runners cannot move into an earlier wave, but you are welcome to move back to a later wave. You do NOT need to inform us of your decision to do this. If you have any problems, please get in touch by phoning 01522 699950. COLOUR RACE APPROX TO THE START WAVE NO. START TIME 1 BLUE A 09:10 2 RED A 09:10 3 PINK A 09:15 4 GREEN A 09:20 5 BLUE B 09:32 6 RED B 09:36 7 PINK B 09:40 8 GREEN B 09:44 9 BLUE C 09:48 10 RED C 09:52 11 PINK C 09:56 12 GREEN C 10:00 VIP BLACK Start Wave Race Colour Race No. First name Surname 11 Pink 1889 Rebecca Aarons Any Black 1890 Jakob Abada 2 Red 4 Susannah Abayomi 3 Pink 1891 Yassen Abbas 6 Red 1892 Nick Abbey 10 Red 1823 Hannah Abblitt 10 Red 1893 Clare Abbott 4 Green 1894 Jon Abbott 8 Green 1895 Jonny Abbott 12 Green 11043 Pamela Abbott 6 Red 11044 Rebecca Abbott 11 Pink 1896 Leanne Abbott-Jones 9 Blue 1897 Emilie Abby Any Black 1898 Jennifer Abecina 6 Red 1899 Philip Abel 7 Pink 1900 Jon Abell 10 Red 600 Kirsty Aberdein 6 Red 11045 Andrew Abery Any Black 1901 Erwann ABIVEN 11 Pink 1902 marie joan ablat 8 Green 1903 Teresa Ablewhite 9 Blue 1904 Ahid Abood 6 Red 1905 Alvin Abraham 9 Blue 1906 Deborah Abraham 6 Red 1907 Sophie Abraham 1 Blue 11046 Mitchell Abrams 4 Green 1908 David Abreu 11 Pink 11047 Kathleen Abuda 10 Red 11048 Annalisa Accascina 4 Green 1909 Luis Acedo 10 Red 11049 Vikas Acharya 11 Pink 11050 Catriona Ackermann -

Electrophysiology-Appnote.Pdf

Application Note: Electrophysiology Electrophysiology Introduction Electrophysiology is a field of research that deals with the electrical properties of cells and biological tissues. In some cases, it is used to test for nervous or cardiac diseases and abnormalities. In many research applications probes are used to measure the electrical activity of individual cells, tissues, and whole specimens. Measuring the activity of cells at various membrane potentials can give valuable information about ion transport mechanisms and cellular communication. Varying ionic strength and membrane potential on cell populations can be used to study contractile movements of muscle cells, and diseases affecting the normal propagation of impulses. Using various stimulation techniques along with a selection of quality equipment and setup design can give rise to a wealth of applications in electrophysiology. Electrophysiology Principle Researchers and clinicians use electrophysiology when studying the electrical properties of neural and muscle tissue. In the clinical laboratory, electroencephalograms are routinely performed as a test for neural disorders like epilepsy, brain tumor, stroke, encephalitis, and others by measuring the electrical activity of the brain through external electrodes. In the research laboratory, electrophysiology methods are used to measure the ion-channel activity of cell membranes in various electrical environments. Here, an extremely thin micropipette is used to make intimate contact with the cell membrane to study membrane potential. Neurons and other cell types derive their electrical properties from their lipid bilayer and the ion concentrations inside and outside of the cell. The ion concentration differences create a membrane potential difference on either side of the membrane. The flow of ions across the membrane generates a current that can be measured using Ohm’s law, where the change in voltage (V) is related to the current (I) and membrane resistance (R). -

Brain Slice Preparation in Electrophysiology

Brain Slice Preparation In structural integrity, unlike cell cultures or tissue homogenates. Electrophysiology Some of the limitations of these preparations are: 1) lack of certain inputs and outputs normally existing in the Avital Schurr, Ph.D. intact brain; 2) certain portions of the sliced tissue, Department of Anesthesiology, especially the top and bottom surfaces of the slice, are University of Louisville School of Medicine, damaged by the slicing action itself; 3) the life span of a Louisville, Kentucky 40292 brain slice is limited and the tissue gets "older" at a much faster rate than the whole animal; 4) the effects of Avital Schurr is currently an Associate Professor in the decapitation ischemia on the viability of the slice are not Department of Anesthesiology at the University of well understood; 5) Since blood-borne factors may be Louisville. He received his Ph.D. in 1977 from Ben- missing from the artificial bathing medium of the brain Gurion University in Beer Sheva, Israel. From 1977 slice, they cannot benefit the preparation and thus the through 1981, he held two postdoctoral positions, one optimal composition of the bathing solution is not yet at the Baylor College of Medicine and the second at established. the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. Brain slice preparations are becoming PREPARATION OF SLICES increasingly popular among neurobiologists for the In general, rodents are the animals of choice for the study of the mammalian central nervous system preparation of brain slices. Of those, the rat and the guinea pig are the most used. After decapitation, the (CNS) in general and synaptic phenomena in brain is removed rapidly from the skull and rinsed with particular. -

Characterization of Embryonic Stem Cell-Differentiated Cells As Mesenchymal Stem Cells

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Honors Theses Honors College Fall 12-2015 Characterization of Embryonic Stem Cell-Differentiated Cells as Mesenchymal Stem Cells Rachael N. Kuehn University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses Part of the Cell Biology Commons Recommended Citation Kuehn, Rachael N., "Characterization of Embryonic Stem Cell-Differentiated Cells as Mesenchymal Stem Cells" (2015). Honors Theses. 349. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/349 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi Characterization of Embryonic Stem Cell-Differentiated Cells as Mesenchymal Stem Cells by Rachael Nicole Kuehn A Thesis Submitted to the Honors College of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science in the Department of Biological Sciences December 2015 ii Approved by ______________________________ Yanlin Guo, Ph.D., Thesis Adviser Professor of Biological Sciences ______________________________ Shiao Y. Wang, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences ______________________________ Ellen Weinauer, Ph.D., Dean Honors College iii ABSTRACT Embryonic stem cells (ESCs), due to their ability to differentiate into different cell types while still maintaining a high proliferation capacity, have been considered as a potential cell source in regenerative medicine. However, current ESC differentiation methods are low yielding and create heterogeneous cell populations. -

Boosting the Cellular Potency of Embryonic Stem Cells by Spliceosome Targeting ✉ Wilfried A

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy www.nature.com/sigtrans RESEARCH HIGHLIGHT OPEN Boosting the cellular potency of embryonic stem cells by spliceosome targeting ✉ Wilfried A. Kues1 Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2021) 6:324; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00743-9 In recent work published in Cell, Shen et al.1 identified transfected ES cells with short interfering RNAs against different spliceosome inhibition in embryonic stem (ES) cells as a key spliceosome transcripts (the spliceosome consisted of 5 core and mechanism for the transition from pluri- to totipotency. Spliceo- several cofactor subunits, here 14 transcripts were targeted), some inhibition, achieved by RNA interference or the chemical respectively. Transient repression of 10 of the 14 splicing factors inhibitor pladienolide B, may gain widespread relevance to the resulted in ES cells, which maintained the typical colony culture of totipotent ES cells, in vitro differentiation of extra- morphology, however, pluripotent marker genes—Oct4 (Pou5f1), embryonal tissue and organoids, translation to the maintenance of Nanog, Sox2, Zfp42 and others—became down-regulated, at the pluripotent cells of other mammal species, including humans, and same time marker genes of totipotency—particularly Zscan4s and a better molecular understanding of cellular potency in stem cells MERVL—were up-regulated. Zscan4s (Zink finger and SCAN and cancer. domain containing 4) is a transcription factor and MERVL (murine The first successful isolation and maintenance of ES derived endogenous retrovirus L) an endogenous retrovirus with a usually fi 1234567890();,: from the inner cell mass (ICM) of murine blastocyst stages was restricted expression to 2-cell embryos. These results were veri ed described in 1981,2 and since then acted as game changer for by supplementing the culture medium with pladienolide B, a genetic studies in this mammalian model organism. -

Magazin Wirtschaft

www.stuttgart.ihk.de 07.2013 Stuttgart - Böblingen - Esslingen-Nürtingen - Göppingen - Ludwigsburg - Rems-Murr Magazin Wirtschaft Ein Service der IHK für Unternehmen in der Region Stuttgart Fachkräfte finden zwischen Alb und Gäu Seite 6 wer hat schon ein ganzes kabinett nur für diewirtschaft? Selbstverständlich wir. Damit die Betriebe gute Rahmenbedingungen haben, sind in unseren Gremien ausschließlich Wirtschaftexperten vertreten. www.stuttgart.ihk.de oder Infoline 0711 2005-0 EDITORIAL Handelskriege kennen keine Gewinner Ähnlich dem Frühjahrswetter in diesem weit kommen? China ist die zweitgrößte Wirt- Jahr ziehen nun auch Wolken über dem schaftsmacht der Welt. Daher sollte das Land Parkett des internationalen Handels beginnen, sich an internationale Spielregeln auf. Auslöser ist die vorläufige Erhebung von zu halten. Globalisierung benötigt faire Wett- EU-Strafzöllen auf chinesische Solarmodule. bewerbsbedingungen, an die sich China zu- China kontert mit einem Anti-Dumping-Ver- weilen jedoch nicht hält. Belegte Fälle von fahren gegen europäischen Wein. Immer Wettbewerbsverstößen gibt es genug. mehr Produkte treten in den Fokus der Dum- ping-Diskussion. Vernünftige Handelspolitik Die EU muss schnellstens sieht anders aus. Mangels Deeskalation wird Verhandlungen aufnehmen die Situation für China und Europa immer tassilo zywietz unangenehmer. Ein Handelskrieg droht. Europa darf davor die Augen nicht ver- Geschäftsführer International Globalisierung erfordert jedoch gegensei- schließen. Nachgiebigkeit ist keine Erfolg ver- der IHK Region Stuttgart tige Rücksichtnahme und Handeln im Sinne sprechende Strategie – damit würde die EU der immer stärker miteinander verbundenen erpressbar. Lässt man China gewähren, kann Volkswirtschaften: China und die EU haben die Methode künftig in der Chemiebranche letztes Jahr Waren und Dienstleistungen in und irgendwann im Autobau angewendet Höhe von über 400 Milliarden Euro ausge- werden. -

A Concise Review on the Classification and Nomenclature of Stem Cells Kök Hücrelerinin S›N›Fland›R›Lmas› Ve Isimlendirilmesine Iliflkin K›Sa Bir Derleme

Review 57 A concise review on the classification and nomenclature of stem cells Kök hücrelerinin s›n›fland›r›lmas› ve isimlendirilmesine iliflkin k›sa bir derleme Alp Can Ankara University Medical School, Department of Histology and Embryology, Ankara, Turkey Abstract Stem cell biology and regenerative medicine is a relatively young field. However, in recent years there has been a tremen- dous interest in stem cells possibly due to their therapeutic potential in disease states. As a classical definition, a stem cell is an undifferentiated cell that can produce daughter cells that can either remain a stem cell in a process called self-renew- al, or commit to a specific cell type via the initiation of a differentiation pathway leading to the production of mature progeny cells. Despite this acknowledged definition, the classification of stem cells has been a perplexing notion that may often raise misconception even among stem cell biologists. Therefore, the aim of this brief review is to give a conceptual approach to classifying the stem cells beginning from the early morula stage totipotent embryonic stem cells to the unipotent tissue-resident adult stem cells, also called tissue-specific stem cells. (Turk J Hematol 2008; 25: 57-9) Key words: Stem cells, embryonic stem cells, tissue-specific stem cells, classification, progeny. Özet Kök hücresi biyolojisi ve onar›msal t›p görece yeni alanlard›r. Buna karfl›n, son y›llarda çeflitli hastal›klarda tedavi amac›yla kullan›labilme potansiyelleri nedeniyle kök hücrelerine ola¤anüstü bir ilgi art›fl› vard›r. Klasik tan›m›yla kök hücresi, kendini yenileme ad› verilen mekanizmayla farkl›laflmadan kendini ço¤altan veya bir dizi farkl›laflma aflamas›ndan geçerek olgun hücrelere dönüflebilen hücrelerdir. -

2013 Kaiser Permanente-Authored Publications Alphabetical by Author

2013 Kaiser Permanente-Authored Publications Alphabetical by Author 1. Abbas MA, Cannom RR, Chiu VY, Burchette RJ, Radner GW, Haigh PI, Etzioni DA Triage of patients with acute diverticulitis: are some inpatients candidates for outpatient treatment? Colorectal Dis. 2013 Apr;15(4):451-7. Southern California 23061533 KP author(s): Abbas, Maher A; Chiu, Vicki Y; Burchette, Raoul J; Radner, Gary W; Haigh, Philip I 2. Abbass MA, Slezak JM, DiFronzo LA Predictors of Early Postoperative Outcomes in 375 Consecutive Hepatectomies: A Single- institution Experience Am Surg. 2013 Oct;79(10):961-7. Southern California 24160779 KP author(s): Abbass, Mohammad Ali; Slezak, Jeffrey M; DiFronzo, Andrew L 3. Abbenhardt C, Poole EM, Kulmacz RJ, Xiao L, Curtin K, Galbraith RL, Duggan D, Hsu L, Makar KW, Caan BJ, Koepl L, Owen RW, Scherer D, Carlson CS, Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium (GECCO) and CCFR, Potter JD, Slattery ML, Ulrich CM Phospholipase A2G1B polymorphisms and risk of colorectal neoplasia Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2013 Sep 12;4(3):140-9. Northern California 24046806 KP author(s): Caan, Bette 4. Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, Horberg MA Primary Care Guidelines for the Management of Persons Infected With HIV: 2013 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Nov 13. Mid-Atlantic 24235263 KP author(s): Horberg, Michael 5. Abraham AG, D'Souza G, Jing Y, Gange SJ, Sterling TR, Silverberg MJ, Saag MS, Rourke SB, Rachlis A, Napravnik S, Moore RD, Klein MB, Kitahata MM, Kirk GD, Hogg RS, Hessol NA, Goedert JJ, Gill MJ, Gebo KA, Eron JJ, Engels EA, Dubrow R, Crane HM, Brooks JT, Bosch RJ, Strickler HD, North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design of IeDEA Invasive cervical cancer risk among HIV-infected women: A North American multi-cohort collaboration prospective study J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. -

Ethical Challenges in Organoid Use

Article Ethical Challenges in Organoid Use Vasiliki Mollaki Hellenic National Bioethics Commission, PC 10674 Athens, Greece; [email protected] Abstract: Organoids hold great promises for numerous applications in biomedicine and biotech- nology. Despite its potential in science, organoid technology poses complex ethical challenges that may hinder any future benefits for patients and society. This study aims to analyze the multifaceted ethical issues raised by organoids and recommend measures that must be taken at various levels to ensure the ethical use and application of this technology. Organoid technology raises several serious ethics issues related to the source of stem cells for organoid creation, informed consent and privacy of cell donors, the moral and legal status of organoids, the potential acquisition of human “characteristics or qualities”, use of gene editing, creation of chimeras, organoid transplantation, commercialization and patentability, issues of equity in the resulting treatments, potential misuse and dual use issues and long-term storage in biobanks. Existing guidelines and regulatory frameworks that are applicable to organoids are also discussed. It is concluded that despite the serious ethical challenges posed by organoid use and biobanking, we have a moral obligation to support organoid research and ensure that we do not lose any of the potential benefits that organoids offer. In this direction, a four-step approach is recommended, which includes existing regulations and guidelines, special regulatory provisions that may be needed, public engagement and continuous monitoring of the rapid advancements in the field. This approach may help maximize the biomedical and social benefits of organoid technology and contribute to future governance models in organoid technology. -

Family Group Sheets Surname Index

PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS SURNAME INDEX This collection of 660 folders contains over 50,000 family group sheets of families that resided in Passaic and Bergen Counties. These sheets were prepared by volunteers using the Societies various collections of church, ceme tery and bible records as well as city directo ries, county history books, newspaper abstracts and the Mattie Bowman manuscript collection. Example of a typical Family Group Sheet from the collection. PASSAIC COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY FAMILY GROUP SHEETS — SURNAME INDEX A Aldous Anderson Arndt Aartse Aldrich Anderton Arnot Abbott Alenson Andolina Aronsohn Abeel Alesbrook Andreasen Arquhart Abel Alesso Andrews Arrayo Aber Alexander Andriesse (see Anderson) Arrowsmith Abers Alexandra Andruss Arthur Abildgaard Alfano Angell Arthurs Abraham Alje (see Alyea) Anger Aruesman Abrams Aljea (see Alyea) Angland Asbell Abrash Alji (see Alyea) Angle Ash Ack Allabough Anglehart Ashbee Acker Allee Anglin Ashbey Ackerman Allen Angotti Ashe Ackerson Allenan Angus Ashfield Ackert Aller Annan Ashley Acton Allerman Anners Ashman Adair Allibone Anness Ashton Adams Alliegro Annin Ashworth Adamson Allington Anson Asper Adcroft Alliot Anthony Aspinwall Addy Allison Anton Astin Adelman Allman Antoniou Astley Adolf Allmen Apel Astwood Adrian Allyton Appel Atchison Aesben Almgren Apple Ateroft Agar Almond Applebee Atha Ager Alois Applegate Atherly Agnew Alpart Appleton Atherson Ahnert Alper Apsley Atherton Aiken Alsheimer Arbuthnot Atkins Aikman Alterman Archbold Atkinson Aimone -

Localized Holes and Delocalized Electrons in Photoexcited Inorganic Perovskites: Watching Each Atomic Actor by Picosecond X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy Fabio G

Localized holes and delocalized electrons in photoexcited inorganic perovskites: Watching each atomic actor by picosecond X-ray absorption spectroscopy Fabio G. Santomauro, Jakob Grilj, Lars Mewes, Georgian Nedelcu, Sergii Yakunin, Thomas Rossi, Gloria Capano, André Al Haddad, James Budarz, Dominik Kinschel, Dario S. Ferreira, Giacomo Rossi, Mario Gutierrez Tovar, Daniel Grolimund, Valerie Samson, Maarten Nachtegaal, Grigory Smolentsev, Maksym V. Kovalenko, and Majed Chergui Citation: Structural Dynamics 4, 044002 (2017); doi: 10.1063/1.4971999 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4971999 View Table of Contents: http://aca.scitation.org/toc/sdy/4/4 Published by the American Institute of Physics Articles you may be interested in Structural enzymology using X-ray free electron lasers Structural Dynamics 4, 044003 (2016); 10.1063/1.4972069 A comparison of the innate flexibilities of six chains in F1-ATPase with identical secondary and tertiary folds; 3 active enzymes and 3 structural proteins Structural Dynamics 4, 044001 (2016); 10.1063/1.4967226 The image of scientists in The Big Bang Theory Physics Today 70, 40 (2017); 10.1063/PT.3.3427 Ultrafast electron crystallography of the cooperative reaction path in vanadium dioxide Structural Dynamics 3, 034304 (2016); 10.1063/1.4953370 A general method for baseline-removal in ultrafast electron powder diffraction data using the dual-tree complex wavelet transform Structural Dynamics 4, 044004 (2016); 10.1063/1.4972518 A beam branching method for timing and spectral characterization of hard X-ray free-electron lasers Structural Dynamics 3, 034301 (2016); 10.1063/1.4939655 STRUCTURAL DYNAMICS 4, 044002 (2017) Localized holes and delocalized electrons in photoexcited inorganic perovskites: Watching each atomic actor by picosecond X-ray absorption spectroscopy Fabio G. -

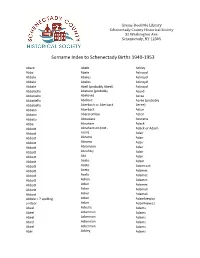

Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953

Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Abare Abele Ackley Abba Abele Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abeles Ackroyd Abbale Abell (probably Abeel) Ackroyd Abbatiello Abelone (probably Acord Abbatiello Abelove) Acree Abbatiello Abelove Acree (probably Abbatiello Aberbach or Aberback Aeree) Abbato Aberback Acton Abbato Abercrombie Acton Abbato Aboudara Acucena Abbe Abraham Adack Abbott Abrahamson (not - Adack or Adach Abbott nson) Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abrams Adair Abbott Abramson Adair Abbott Abrofsky Adair Abbott Abt Adair Abbott Aceto Adam Abbott Aceto Adamczak Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Aceto Adamec Abbott Acken Adamec Abbott Acker Adamec Abbott Acker Adamek Abbott Acker Adamek Abbzle = ? spelling Acker Adamkiewicz unclear Acker Adamkiewicz Abeel Ackerle Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abeel Ackerman Adams Abel Ackley Adams Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave. Schenectady, NY 12305 Surname Index to Schenectady Births 1940-1953 Adams Adamson Ahl Adams Adanti Ahles Adams Addis Ahman Adams Ademec or Adamec Ahnert Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahren Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adinolfi Ahrendtsen Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adkins Ahrens Adams Adriance Ahrens Adams Adsit Aiken Adams Aeree Aiken Adams Aernecke Ailes = ? Adams Agans Ainsworth Adams Agans Aker (or Aeher = ?) Adams Aganz (Agans ?) Akers Adams Agare or Abare = ? Akerson Adams Agat Akin Adams Agat Akins Adams Agen Akins Adams Aggen Akland Adams Aggen Albanese Adams Aggen Alberding Adams Aggen Albert Adams Agnew Albert Adams Agnew Albert or Alberti Adams Agnew Alberti Adams Agostara Alberti Adams Agostara (not Agostra) Alberts Adamski Agree Albig Adamski Ahave ? = totally Albig Adamson unclear Albohm Adamson Ahern Albohm Adamson Ahl Albohm (not Albolm) Adamson Ahl Albrezzi Grems-Doolittle Library Schenectady County Historical Society 32 Washington Ave.