'A Revolution in Art': Maria Callcott on Poussin, Painting, and the Primitives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ġstanbul Teknġk Ünġversġtesġ Sosyal

ĠSTANBUL TEKNĠK ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ ĠNGĠLĠZ SANAT DERGĠLERĠNDE TÜRK SANATI (1903-2010 MAYIS) : KĠTAP TANITIM YAZILARI VE MAKALELER ÜZERĠNE GENEL BĠR DEĞERLENDĠRME YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Neslihan DOĞAN Anabilim Dalı : Sanat Tarihi Programı : Sanat Tarihi Tez DanıĢmanı: Doç. Dr. Aygül AĞIR HAZĠRAN 2010 ĠSTANBUL TEKNĠK ÜNĠVERSĠTESĠ SOSYAL BĠLĠMLER ENSTĠTÜSÜ ĠNGĠLĠZ SANAT DERGĠLERĠNDE TÜRK SANATI (1903-2010 MAYIS): KĠTAP TANITIM YAZILARI VE MAKALELER ÜZERĠNE GENEL BĠR DEĞERLENDĠRME YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ Neslihan DOĞAN (402941020) Tezin Enstitüye Verildiği Tarih : 26 Nisan 2010 Tezin Savunulduğu Tarih : 11 Haziran 2010 Tez DanıĢmanı : Doç. Dr. Aygül AĞIR (ĠTÜ) Diğer Jüri Üyeleri : Doç. Dr. Zeynep KUBAN (ĠTÜ) Yrd. Doç. Dr. Tarkan OKÇUOĞLU(ĠÜ) HAZĠRAN 2010 ÖNSÖZ Bu yüksek lisans tez çalışmasında İngilizlerin gözünden Türk sanatını incelemek amaçlanmaktadır. Bu döneme kadar akademik çalışmalarda Türk Sanatı farklı şekillerde ortaya konmuş ve değerli çalışmalar yapılmıştır. Batılı yabancı uzmanlar ve araştırmacılar tarafından yapılan birçok değerli araştırmalar günümüze kadar gelmistir. Osmanlı İmparatorluğu döneminden bu yana dünyadaki en büyük imparatorluklardan biri olan Britanya Krallığı ile geçmişten günümüze politik ilişkiler devam etmektedir. Bu tez sadece Britanya Krallığı olarakda adlandırılan İngiltere‟deki yayınevlerine ait İngiliz Sanat Dergileri ve bu dergilerde yayınlanan kitap tanıtım yazıları ve makalelerin incelenmesi ve değerlendirilmesi yolu ile bu dergilerdeki Türk Sanatı çalışmalarına odaklanmaktadır. Bu çalışmada -

Urban Geology in Chelsea: a Stroll Around Sloane Square Ruth Siddall

Urban Geology in London No. 33 Urban Geology in Chelsea: A Stroll Around Sloane Square Ruth Siddall Situated in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, Sloane Square SW1, and several of the neighbouring streets are named after Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) who lived in the area in the mid 18th Century. The area is now owned by the Cadogan Estate Ltd. The Cadogan family inherited this from Sloane via his daughter, Elizabeth and it is still the hands of the 8th Earl Cadogan. The eldest sons of this family inherit the title Viscount Chelsea and this area is one of the top pieces of real estate in the country, earning the family over £5 billion per year. It is correspondingly a pleasant area to stroll around, the home to designer shops, the Saatchi Gallery as well as a theatre and concert venue. Development took place between the mid 19th Century and the present day and displays a range of stones fairly typical of London Building during this period – along with a few surprises. Fountain, Sloane Square, with Peter Jones Department Store behind. This walk starts at Sloane Square Underground Station on Holbein Place, and takes in the Square itself, the southern end of Sloane Street, Duke of York Square and the eastern end of the King’s Road. It is easy to return to Sloane Square station when finished, or you could visit the Saatchi Gallery which displays a collection of contemporary art to suit all tastes (and none). For the buildings described below, architectural information below is derived from Pevsner’s guide to North West London (Cherry & Pevsner, 1991), unless otherwise cited. -

Articled to John Varley

N E W S William Blake & His Followers Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 16, Issue 3, Winter 1982/1983, p. 184 PAGE 184 BLAKE AN I.D QlJARThRl.) WINTER 1982-83 NEWSLETTER WILLIAM BLAKE & HIS FOLLOWERS In conjunction with the exhibition William Blake and His Followers at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Morton D. Paley (Univ. of California, Berkeley) delivered a lecture, "How Far Did They Follow?" on 16 January BLAKE AT CORNELL 1983. Cornell University will host Blake: Ancient & Modern, a symposium 8-9 April 1983, exploring the ways in which the traditions and techniques of printmaking and painting JOHN LINNELL: A CENTENNIAL EXHIBITION affected Blake's poetry, art, and art theory. The sym- posium will also discuss Blake's late prints and the prints We have received the following news release from the of his followers, and examine the problems of teaching Yale Center for British Art: in college an interdisciplinary artist like William Blake. The first retrospective exhibition in America of the Panelists and speakers include M. H. Abrams, Esther work of John Linnell will open at the Yale Center for Dotson, Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, Peter Kahn, British Art on Wednesday, 26 January. Karl Kroeber, Reeve Parker, Albert Roe, Jon Stallworthy, John Linnell was born in London on 16 June 1792. He and Joseph Viscomi. died ninety years later, after a long and successful career The symposium is being held in conjunction with two ex- which spanned a century of unprecedented change in hibitions: The Prints of Blake and his Followers, Johnson Britain. -

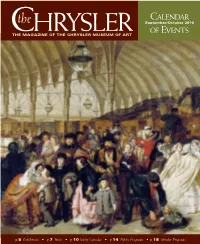

Calendar of Events

Calendar the September/October 2010 hrysler of events CTHE MAGAZINE OF THE CHRYSLER MUSEUM OF ART p 5 Exhibitions • p 7 News • p 10 Daily Calendar • p 14 Public Programs • p 18 Member Programs G ENERAL INFORMATION COVER Contact Us The Museum Shop Group and School Tours William Powell Frith Open during Museum hours (English, 1819–1909) Chrysler Museum of Art (757) 333-6269 The Railway 245 W. Olney Road (757) 333-6297 www.chrysler.org/programs.asp Station (detail), 1862 Norfolk, VA 23510 Oil on canvas Phone: (757) 664-6200 Cuisine & Company Board of Trustees Courtesy of Royal Fax: (757) 664-6201 at The Chrysler Café 2010–2011 Holloway Collection, E-mail: [email protected] Wednesdays, 11 a.m.–8 p.m. Shirley C. Baldwin University of London Website: www.chrysler.org Thursdays–Saturdays, 11 a.m.–3 p.m. Carolyn K. Barry Sundays, 12–3 p.m. Robert M. Boyd Museum Hours (757) 333-6291 Nancy W. Branch Wednesday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m. Macon F. Brock, Jr., Chairman Thursday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Historic Houses Robert W. Carter Sunday, 12–5 p.m. Free Admission Andrew S. Fine The Museum galleries are closed each The Moses Myers House Elizabeth Fraim Monday and Tuesday, as well as on 323 E. Freemason St. (at Bank St.), Norfolk David R. Goode, Vice Chairman major holidays. The Norfolk History Museum at the Cyrus W. Grandy V Marc Jacobson Admission Willoughby-Baylor House 601 E. Freemason Street, Norfolk Maurice A. Jones General admission to the Chrysler Museum Linda H. -

Unlocking Eastlake Unlocking Eastlake

ng E nlocki astlak U e CREATED BY THE YOUNG EXPLAINERS OF PLYMOUTH CITY MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY No. 1. ] SEPTEMBER 22 - DECEMBER 15, 2012. [ One Penny. A STROKE OF GENIUS. UNLOCKING EASTLAKE UNLOCKING EASTLAKE It may be because of his reserved nature that Staff at the City Museum and Art Gallery are organising a range of events connected to the Eastlake is not remembered as much as he exhibition, including lunchtime talks and family-friendly holiday workshops. INTRODUCING deserves to be. Apart from securing more Visit www.plymouth.gov.uk/museumeastlake to stay up to date with what’s on offer! than 150 paintings for the nation, Eastlake was a key figure in helping the public gain like to i uld ntro a better understanding of the history of wo d uc WALKING TRAILS e e EASTLAKE western art. Through detailed catalogues, W THE simpler ways of picture display, and the Thursday 20th September 2012: : BRITISH ART’S PUBLIC SERVANT introduction of labels enabling free access to Grand Art History Freshers Tour information, Eastlake gave the us public art. YOUNG EXPLAINERS A chance for Art History Freshers to make friends as well as see what lmost 150 years after his Article: Laura Hughes the Museum and the Young Explainers death, the name of Sir Charles Children’s Actities / Map: Joanne Lees have to offer. The tour will focus on UNLOCKING EASTLAKE’S PLYMOUTH Eastlake has failed to live up to Editor: Charlotte Slater Eastlake, Napoleon and Plymouth. the celebrity of his legacy. Designer: Sarah Stagg A Illustrator (front): Alex Hancock Saturday 3rd November 2012: Even in his hometown of Plymouth, blank faces During Eastlake’s lifetime his home city Illustrator (inside): Abi Hodgson Lorente Eastlake’s Plymouth: usually meet the question: “Who is Sir Charles of Plymouth dramatically altered as it A Family Adventure Through Time Eastlake?” Yet this cultural heavyweight was transformed itself from an ancient dockland Alice Knight Starting at the Museum with interactive acknowledged to be one of the ablest men of to a modern 19th century metropolis. -

Buses from Battersea Park

Buses from Battersea Park 452 Kensal Rise Ladbroke Grove Ladbroke Grove Notting Hill Gate High Street Kensington St Charles Square 344 Kensington Gore Marble Arch CITY OF Liverpool Street LADBROKE Royal Albert Hall 137 GROVE N137 LONDON Hyde Park Corner Aldwych Monument Knightsbridge for Covent Garden N44 Whitehall Victoria Street Horse Guards Parade Westminster City Hall Trafalgar Square Route fi nder Sloane Street Pont Street for Charing Cross Southwark Bridge Road Southwark Street 44 Victoria Street Day buses including 24-hour services Westminster Cathedral Sloane Square Victoria Elephant & Castle Bus route Towards Bus stops Lower Sloane Street Buckingham Palace Road Sloane Square Eccleston Bridge Tooting Lambeth Road 44 Victoria Coach Station CHELSEA Imperial War Museum Victoria Lower Sloane Street Royal Hospital Road Ebury Bridge Road Albert Embankment Lambeth Bridge 137 Marble Arch Albert Embankment Chelsea Bridge Road Prince Consort House Lister Hospital Streatham Hill 156 Albert Embankment Vauxhall Cross Vauxhall River Thames 156 Vauxhall Wimbledon Queenstown Road Nine Elms Lane VAUXHALL 24 hour Chelsea Bridge Wandsworth Road 344 service Clapham Junction Nine Elms Lane Liverpool Street CA Q Battersea Power Elm Quay Court R UE R Station (Disused) IA G EN Battersea Park Road E Kensal Rise D ST Cringle Street 452 R I OWN V E Battersea Park Road Wandsworth Road E A Sleaford Street XXX ROAD S T Battersea Gas Works Dogs and Cats Home D A Night buses O H F R T PRINCE O U DRIVE H O WALES A S K V Bus route Towards Bus stops E R E IV A L R Battersea P O D C E E A K G Park T A RIV QUEENST E E I D S R RR S R The yellow tinted area includes every Aldwych A E N44 C T TLOCKI bus stop up to about one-and-a-half F WALE BA miles from Battersea Park. -

Artists` Picture Rooms in Eighteenth-Century Bath

ARTISTS' PICTURE ROOMS IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BATH Susan Legouix Sloman In May 1775 David Garrick described to Hannah More the sense of well being he experienced in Bath: 'I do this, & do that, & do Nothing, & I go here and go there and go nowhere-Such is ye life of Bath & such the Effects of this place upon me-I forget my Cares, & my large family in London, & Every thing ... '. 1 The visitor to Bath in the second half of the eighteenth century had very few decisions to make once he was safely installed in his lodgings. A well-established pattern of bathing, drinking spa water, worship, concert and theatre-going and balls meant that in the early and later parts of each day he was likely to be fully occupied. However he was free to decide how to spend the daylight hours between around lOam when the company generally left the Pump Room and 3pm when most people retired to their lodgings to dine. Contemporary diaries and journals suggest that favourite daytime pursuits included walking on the parades, carriage excursions, visiting libraries (which were usually also bookshops), milliners, toy shops, jewellers and artists' showrooms and of course, sitting for a portrait. At least 160 artists spent some time working in Bath in the eighteenth century,2 a statistic which indicates that sitting for a portrait was indeed one of the most popular activities. Although he did not specifically have Bath in mind, Thomas Bardwell noted in 1756, 'It is well known, that no Nation in the World delights so much in Face-painting, or gives so generous Encouragement to it as our own'.3 In 1760 the Bath writer Daniel Webb noted 'the extraordinary passion which the English have for portraits'.4 Andre Rouquet in his survey of The Present State of the Arts in England of 1755 described how 'Every portrait painter in England has a room to shew his pictures, separate from that in which he works. -

“The China of Santa Cruz”: the Culture of Tea in Maria Graham's

“The China of Santa Cruz”: The Culture of Tea in Maria Graham’s Journal of a Voyage to Brazil (Article) NICOLLE JORDAN University of Southern Mississippi he notion of Brazilian tea may sound like something of an anomaly—or impossibility—given the predominance of Brazilian coffee in our cultural T imagination. We may be surprised, then, to learn that King João VI of Portugal and Brazil (1767–1826) pursued a project for the importation, acclimatization, and planting of tea from China in his royal botanic garden in Rio de Janeiro. A curious episode in the annals of colonial botany, the cultivation of a tea plantation in Rio has a short but significant history, especially when read through the lens of Maria Graham’s Journal of a Voyage to Brazil (1824). Graham’s descriptions of the tea garden in this text are brief, but they amplify her thorough-going enthusiasm for the biodiversity and botanical innovation she encountered— and contributed to—in South America. Such enthusiasm for the imperial tea garden echoes Graham’s support for Brazilian independence, and indeed, bolsters it. In 1821 Graham came to Brazil aboard HMS Doris, captained by her husband Thomas, who was charged with protecting Britain’s considerable mercantile interests in the region. As a British naval captain’s wife, she was obliged to uphold Britain’s official policy of strict neutrality. Despite these circumstances, her Journal conveys a pro-independence stance that is legible in her frequent rhapsodies over Brazil’s stunning flora and fauna. By situating Rio’s tea plantation within the global context of imperial botany, we may appreciate Graham’s testimony to a practice of transnational plant exchange that effectively makes her an agent of empire even in a locale where Britain had no territorial aspirations. -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10

Eastlake's Scholarly and Artistic Achievements Wednesday 10 October 2012 Lizzie Hill & Laura Hughes Overview I will begin this Art Bite with a quotation from A Century of British Painters by Samuel and Richard Redgrave, who refer to Eastlake as one of "a few exceptional painters who have served the art they love better by their lives than their brush" . This observation is in keeping with the norm of contemporary views in which Eastlake is first and foremost seen as an art historian and collector. However, as a man who began his career as a painter, it seems it would be interesting to explore both of these aspects of his life. Therefore, this Art Bite will be examining the validity of this critique by evaluating Eastlake's artistic outputs and scholarly achievements, and putting these two aspects of his life in direct relation to each other. By doing this, the aim behind this Art Bite is to uncover the fundamental reason behind Eastlake's contemporary and historical reputation, and ultimately to answer; - What proved to be Eastlake's best weapon in entering the Art Historical canon: his brain or his brush? Introduction So, who was Sir Charles Lock Eastlake? To properly be able to compare his reputation as an art historian versus being a painter himself, we need to know the basic facts about the man. A very brief overview is that Eastlake was born in Plymouth in 1793 and from an early age was determined to be a painter. He was the first student of the notable artist Benjamin Haydon in January 1809 and received tuition from the Royal Academy schools from late 1809. -

LONDON Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

LONDON Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | London | 2019 0 For decades London has led the way in terms of innovation, fashion and retail trends. It is the focal location for new retailers seeking representation in the United Kingdom. London plays a key role on the regional, national and international stage. It is a top target destination for international retailers, and has attracted a greater number of international brands than any other city globally. Demand among international retailers remains strong with high profile deals by the likes of Microsoft, Samsung, Peloton, Gentle Monster and Free People. For those adopting a flagship store only strategy, London gives access to the UK market and is also seen as the springboard for store expansion to the rest of Europe. One of the trends to have emerged is the number of retailers upsizing flagship stores in London; these have included Adidas, Asics, Alexander McQueen, Hermès and Next. Another developing trend is the growing number of food markets. Openings planned include Eataly in City of London, Kerb in Seven Dials and Market Halls on Oxford Street. London is the home to 8.85 million people and hosting over 26 million visitors annually, contributing more than £11.2 billion to the local economy. In central London there is limited retail supply LONDON and retailers are showing strong trading performances. OVERVIEW Cushman & Wakefield | London | 2019 1 LONDON KEY RETAIL STREETS & AREAS CENTRAL LONDON MAYFAIR Central London is undoubtedly one of the forefront Mount Street is located in Mayfair about a ten minute walk destinations for international brands, particularly those from Bond Street, and has become a luxury destination for with larger format store requirements. -

Mulready Stationery

BRITISH PHILATELIC BULLETIN is for... Mulready stationery Colin Baker charts the brief life of William Mulready’s illustrated envelopes, commissioned to grace the first ever prepaid stationery of 1840 One of the innovations that came with the postal reforms of 1840 was the introduction of prepaid envelopes and letter sheets; the Id values were printed in black and the 2d values in blue. These could be used for letters sent anywhere in the L K, weighing up to half an ounce and one ounce respectively. Neither the envelopes nor the letter sheets were gummed (it would be another five to ten years before that was possible) and they had to be folded by hand and sealed with a blob of wax or fastened with a wafer seal - a small piece of paper carrying a design or message that was stuck over the point of the flap to hold it in place. They were launched on the same day the new Id and 2d adhesive stamps - the famous Penny Black and Twopenny Blue - came into use. It was assumed that the convenience of Fig 1 prepaid stationery would make it an instantly popular choice. So, while the printed envelopes and letter sheets were stocked in large numbers at every post office, the adhesive stamps were harder to find - on the issue date of 6 May 1840, there were only limited supplies of the Penny Black and none at all of the Twopenny Blue. The stationery was illustrated by William Mulready, a talented artist and member of the Royal Academy, influenced by Rowland Hill and Henry Cole (the two men in charge of introducing the postal reforms).