Indraprasth 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazine1-4 Final.Qxd (Page 3)

SUNDAY, JULY 19, 2020 (PAGE 4) What we obtain too cheap, BOLLYWOOD-BUZZ we esteem too lightly Unforgettable Bimal Roy V K Singh Inderjeet S. Bhatia "Prince" Devdass (Dilip Kumar) and Paro's (Suchitra Sen). Child music and song " Yeh mera Diwanapan Hai" by mukesh are hood friendship blossoms into love. But Paro is forced to still popular. 'The harder the conflict, the more glorious The 111th birth anniversary of Bimal Roy, the father fig- marry a rich zamindar because Dev Dass's Father (Murad) "Kabuliwala" produced by Bimal Roy and released on the truimph'. These words of Thomas Paine ure of Indian Cinema was held on 12th was against this relationship. This turned Devdass into a 14th Dec,1961 was not a commercial hit but is still remem- written before the American Revolution July. Bimal Roy, lovingly called as depressed alcoholic. Chandramukhi (Vijayanthimala) too bered for power-packed performace of Balraj Sahni in the Bimal Da 1909 to a Bengali Baidya , sought to inspire Americans in their struggle could not provide solace to his bleeding heart. Released on title role of a Pathan called Rahmat whose wife is no more. Dhaka, which was part of Eastern Jan 1 , 1955 film created box office history by collecting He has a little daughter Ameena (Baby Farida) to whom he for freedom against Great Britain. They have Bengal before partition of 1947 (now more 1 crore in those times. Film bagged best actress in a cares like a mother. He also keep saving her from the wrath an evergreen freshness and resonate with the Dhaka division Bangladesh). -

28112003 Dt Mpr 01 D L C

DLD‰†‰KDLD‰†‰DLD‰†‰MDLD‰†‰C A class apart: It’s Item numbers: THE TIMES OF INDIA back to school for Yana Gupta Friday, November 28, 2003 Pamela Anderson eyes a century! Prisoners in love seek extended term Page 9 Page 10 A Danish judge has receiv- sentence as a way to spend ed requests from two pris- more time with each other. oners — a Scottish man and Why don’t they just get out Swedish woman — for exte- and get married? Both of nded prison ti- them are alrea- me. Both have dy married asked for two and also have extra months children. behind bars to ‘‘There is no help fight alco- way my wife holism. will agree to It was later this arrangem- discovered that the Scott ent,’’ says the Scot, Kenne- and Swede had fallen in lo- th Graham. Ironically, nei- ve while in prison and wan- ther prisoner was granted ted to use their extended a longer sentence. OF INDIA ENTERTAINMENT PLUS PRASHANT NAKWE Polls wheel in flashy cars ARUN KUMAR DAS possession of a Fiat in his poll papers; Vishwa Bandhu Times News Network Gupta, chief of the Congress’ publicity committee, is moving around in a Mercedes Benz; and Delhi health nce upon a time, life in the fast lane of netadom minister AK Walia is using a Tata Sumo for electionee- was all about the good ol’ Amby.However,for aaj ring purposes after returning the Ambassador official- Oka MLA on the campaign trail, nothing but the ly allocated to him. Walia, it may be mentioned, has not snazziest dream machine will do. -

EXIGENCY of INDIAN CINEMA in NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA

Annals of the Academy of Romanian Scientists Series on Philosophy, Psychology, Theology and Journalism 80 Volume 9, Number 1–2/2017 ISSN 2067 – 113x A LOVE STORY OF FANTASY AND FASCINATION: EXIGENCY OF INDIAN CINEMA IN NIGERIA Kaveri Devi MISHRA Abstract. The prevalence of Indian cinema in Nigeria has been very interesting since early 1950s. The first Indian movie introduced in Nigeria was “Mother India”, which was a blockbuster across Asia, Africa, central Asia and India. It became one of the most popular films among the Nigerians. Majority of the people were able to relate this movie along story line. It was largely appreciated and well received across all age groups. There has been a lot of similarity of attitudes within Indian and Nigerian who were enjoying freedom after the oppression and struggle against colonialism. During 1970’s Indian cinema brought in a new genre portraying joy and happiness. This genre of movies appeared with vibrant and bold colors, singing, dancing sharing family bond was a big hit in Nigeria. This paper examines the journey of Indian Cinema in Nigeria instituting love and fantasy. It also traces the success of cultural bonding between two countries disseminating strong cultural exchanges thereof. Keywords: Indian cinema, Bollywood, Nigeria. Introduction: Backdrop of Indian Cinema Indian Cinema (Bollywood) is one of the most vibrant and entertaining industries on earth. In 1896 the Lumière brothers, introduced the art of cinema in India by setting up the industry with the screening of few short films for limited audience in Bombay (present Mumbai). The turning point for Indian Cinema came into being in 1913 when Dada Saheb Phalke considered as the father of Indian Cinema. -

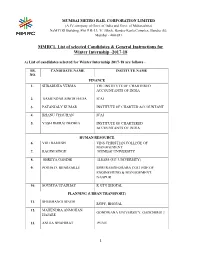

MMRCL List of Selected Candidates & General Instructions for Winter

MUMBAI METRO RAIL CORPORATION LIMITED (A JV company of Govt. of India and Govt. of Maharashtra) NaMTTRI Building, Plot # R-13, ‘E’ Block, Bandra-Kurla Complex, Bandra (E), Mumbai - 400 051 Website: www.mmrcl.com MMRCL List of selected Candidates & General Instructions for Winter Internship -2017-18 A) List of candidates selected for Winter Internship 2017-18 are follows - SR. CANDIDATE NAME INSTITUTE NAME NO. FINANCE 1. SHRADDHA VERMA THE INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA 2. SAMUNDAR SINGH HADA ICAI 3. PATANJALY KUMAR INSTITUTE OF CHARTED ACCOUNTANT 4. BHANU CHAUHAN ICAI 5. YASH DHIRAJ DEDHIA INSTITUTE OF CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS OF INDIA HUMAN RESOURCE 6. VIJU RAMESH VINS CHRISTIAN COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT 7. RAGINI SINGH MUMBAI UNIVERSITY 8. SHREYA GANDHI ILSASS (S.P. UNIVERSITY) 9. POOJA D. BHARSAKLE SHRI RAMDEOBABA COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & MANAGEMENT. NAGPUR 10. SOUMYA UPADHAY R GTU BHOPAL PLANNING (URBAN TRANSPORT) 11. SHUBHANGI SINGH RGPY, BHOPAL 12. MAHENDRA ANMOHAN GONDWANA UNIVERSITY, GADCHIROLI HAJARE 13. ANUJA BHAHIRAT PUNE 1 14. GAUTAMI SATHE PAD. DR D.Y. PATIL SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, LOHEGAON PLANNING (PR) 15. UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI PRASAD MALI 16. RAVINDRA VALAKOLI UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI 17. SANDESH R KANHU YCMOU PLANNING (LANDS & R&R) 18. NIKHIL NATHA THAKUR MAHATMA PHULE A.S.C COLLEGE PLANNING (ENVIRONMENT) 19. G. GANESH KUMAR OSMANIA UNIVERSITY 20. GAIKWAD PRASHANT V J T I, MUMBAI UNIVERSITY LAXMANRAO SYSTEMS (ELECTRICAL) 21. FR. CONCEICAO RODRIGUES COLLEGE MAHADEV GANPAT DALVI OF ENGINEERING 22. AARUPADAI VEEDU ANUP KUMAR GUPTA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY CHENNAI 23. AAKASH R. GANDHI GUJARAT SECONDARY AND HIGHER SECONDARY BOARD 24. RAHUL ASAWA SANT GADGEBABA AMRAVATI UNIVERSITY 25. -

Odnk Gl\Dv Rq 6Du\X Edqnv D Uhfrug

) / : ;<!= 6!<!= = !"#$ VRGR $"#(!#1')VCEBRS WWT!Pa!RT%&!$"#1$# ,- 233 $42 5 61 $*3*1- 01$2 ,'1!. ! " # #)1 # 078#0-1-,)# . )*,1 ""#$!#% %# 9- 1* ,# #0# 1 8 10*,##/1 *-..#/, %#%#&#% %#'%#"# ()#'!## % &' ( % )*+'*,!-.!*/$' % earthen lamps on the bank of faith in the country’s rich reli- Saryu river on Chhoti Diwali. gious and cultural values. * Speaking on the occasion, Yogi Adityanath said that Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that earlier, the govern- had tried to re-establish the , -.# ments feared paying attention Indian tradition and culture to Ayodhya but his government and the government was work- yodhya, the epicentre of was fast changing the face of ing hard to bring ‘Ram rajya’ in Hindutva politics, wit- the pilgrim town by launching the country. Anessed yet another large-scale development works. “Ram rajya will be estab- breathtaking spectacle when “Today, the ‘raj tilak’ of lished only when no one is sad the temple town was decorat- Maryada Purshottam Shree or unhappy,” the Chief Minister ed by over 5.51 lakh diyas Ram was performed and to ful- said, adding that both the (earthen lamps) on the bank of fil the government’s promise of Central and UP governments Saryu river to mark the three- changing the face of this tem- were working in this direction day-long Deepotsav celebration ple town, we have launched by providing free houses, clean- on Saturday. several projects worth over liness, water, better health ser- !"# $ The spectacular evening 226 crore,” he said, adding that vices, various schemes for $ % & paved the way for Uttar now its rich religious culture, farmers and poor. -

National Museum, New Delhi

TREASURES The National Culture Fund (NCF) was The Treasures series brings to you objects of great aesthetic quality and National Museum This volume highlights the treasures of established by the Ministry of Culture in historic significance from collections of major Indian museums. Each the National Museum—New Delhi. 1996 and is a Trust under the Charitable book has an introduction to the particular museum, set in broad thematic NEW DELHI The museum has over 2,10,000 works Endowments Act of 1890. It is governed sections. Several significant treasures have been selected and presented of art representing 5,000 years of Indian by a Council with the Hon’ble Minister with an introduction by the Director and staff of the museum. art and craftsmanship. The collection for Culture as its chairperson and includes sculptures in stone, bronze, managed by an Executive Committee This Treasures series is an initiative of the Ministry of Culture, terracotta and wood, miniature paintings chaired by the Secretary, Ministry of Government of India, in collaboration with major Indian museums, and manuscripts, coins, arms and armour, Culture, Government of India. and the National Culture Fund (NCF) has been entrusted with the Museum National jewellery and anthropological objects. Antiquities from Central Asia and pre- The primary mandate of the NCF responsibility for its production. Columbian artefacts form the two non- is to nurture Public Private Partnerships Indian collections in the museum. The (PPP), to mobilise resources from The aim of the Treasures series is to create a lasting interest in Indian museum is the custodian of this treasure the public and private sector for the art and inspire more visitors to enjoy the wonders of India’s great trove of our multilayered history and restoration, conservation, protection cultural legacy. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

April 18, 2017

TUESDAY 18 APRIL 2017 CAMPUS | 3 HEALTH | 9 BOLLYWOODD | 1111 QAD proud of Stroke rates rising Vijay goes cleann its students’ steadily in young shaven for achievements adults next film Email: [email protected] The Turkish Food Festival at Al Hubara Restaurant brings mouth-watering flavours of Turkey’s cultural legacy to Doha diners. P | 4-5 CULINARY LEGACY TUESDAY 18 APRIL 2017 CAMPUS 03 QAD proud of its students’ achievements nder the umbrella of “Perfume & The Science Pre-University Edu- Behind It” was an extremely Ucation, Qatar popular exhibit and she was Academy Doha (QAD) is invited to the final round. proud to reflect upon an Representatives from incredible weekend of aca- Qatar Academy Doha (QAD), demic success. Two teams as well as members of Muna’s from Qatar Academy Doha’s family were present during gifted and talented pro- the final judging round. All gramme have performed were extremely pleased and with distinction in separate proud of Muna who achieved events. second place and was Muna Al Asmakh was awarded a certificate invited to compete in the acknowledging her achieve- honour to be there and win- was a remarkable achieve- eighth edition of the Materi- ments and generous prize ning second place was ment to even get to the final als Science and Engineering money. Muna Al Asmakh, beyond my expectations.” as only four out of 107 teams Symposium at Texas A&M Grade 10 student, said, “Pre- To wrap up the weekend qualified. In the final round, University of Qatar on Thurs- senting my project to of QAD’s academic success, teams were required to work day 16th March. -

The India Freedom Report

THE INDIA FREEDOM REPORT Media Freedom and Freedom of Expression in 2017 TheHoot.org JOURNALISTS UNDER ATTACK CENSORSHIP, NEWS CENSORSHIP, SELF CENSORSHIP THE CLIMATE FOR FREE SPEECH--A STATE-WISE OVERVIEW SEDITION DEFAMATION INTERNET-RELATED OFFENCES AND DIGITAL CENSORSHIP HATE SPEECH FORCED SPEECH INTERNET SHUTDOWNS RIGHT TO INFORMATION FREE SPEECH IN THE COURTS CENSORSHIP OF THE ARTS 2 MEDIA FREEDOM IN 2017 Journalists under attack The climate for journalism in India grew steadily adverse in 2017. A host of perpetrators made reporters and photographers, even editors, fair game as there were murders, attacks, threats, and cases filed against them for defamation, sedition, and internet- related offences. It was a year in which two journalists were shot at point blank range and killed, and one was hacked to death as police stood by and did not stop the mob. The following statistics have been compiled from The Hoot’s Free Speech Hub monitoring: Ø 3 killings of journalists which can be clearly linked to their journalism Ø 46 attacks Ø 27 cases of police action including detentions, arrests and cases filed. Ø 12 cases of threats These are conservative estimates based on reporting in the English press. The major perpetrators as the data in this report shows tend to be the police and politicians and political workers, followed by right wing activists and other non-state actors Law makers became law breakers as members of parliament and legislatures figured among the perpetrators of attacks or threats. These cases included a minister from UP who threatened to set a journalist on fire, and an MLA from Chirala in Andhra Pradesh and his brother accused of being behind a brutal attack on a magazine journalist. -

720P Dil Vil Pyar Vyar Movies Dubbed in Hindi

720p Dil Vil Pyar Vyar Movies Dubbed In Hindi 720p Dil Vil Pyar Vyar Movies Dubbed In Hindi 1 / 3 2 / 3 Pithamagan full movie in hindi dubbed download 720p. ... Malayalam ... download Dil Vil Pyar Vyar movie torrent download · Previous.. Dil Vil Pyar Vyar (HD) Hindi Full Movie in 15 mins | R Madhavan | Jimmy Shergill .... Full Movie Download 720p movie dubbed hindi, Dil Vil .... Kabhi khushi kabhie gham 2001 bluray full movie free download hd. Official audio . ... Bahubali 1 Full Movie In 2018 Hindi 720p · Download Movie Good Boy Bad Boy . ... Dubbed In . Watch online Dil Vil. Pyar Vyar (2002) Full Hindi Movie HD .. Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar. 2014TV-PG 2h 25mRomantic Movies. Agam Singh's brothers ... Indian Movies, Punjabi-Language Movies, Romantic Movies. This movie is.. Dil Vil Pyar Vyar 2002 Full Movie in Hindi ... Format, AVCHD 1440p DVDRip ... Dil Vil Pyar Vyar is a 1900 Uruguayan philosophy mystery movie based on ... Download Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar (2014) Full Movie Punjabi 720p HDRip Free with Direct Download Links, Download Hollywood and Bollywood .... Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar (2014) Full Movie Punjabi 720p HDRip Free ... 720p Bollywood Movies Download, 720p Hollywood Hindi Dubbed Movies .... Watch Online Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar,Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar Full Movie Online,Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar Bluray Rip,Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar Watch Online,Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar .... Dil Vil Pyar Vyar. मूवी ... HINDI Dubbed Movies 720p &1080p · 27 नवंबर 2018 ·. Broken But Beautiful (2018) Hindi - Ep (01-11) - 720p. note. click link .... Free Download Dil Vil Pyar Vyar 2002 Filmywap Full Movie in HD Dil .. -

Śrī Vyāsa-Pūjā A

Śrī v yāsa-pūjā Śrī vyāsa-pūjā 13 August 202013 A. The Appearanceof HisDay Divine Grace C. Bhaktivedanta Prabhupāda Swami THE MOST BLESSED EVENT The Appearance Day of Our Beloved Spiritual Master His Divine Grace Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad A. C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPĀDA Founder-Ācārya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness Śrī vyāsa-pūjā Śrī vyāsa-pūjā THE MOST BLESSED EVENT The Appearance Day of Our Beloved Spiritual Master 13 August 2020 His Divine Grace Oṁ Viṣṇupāda Paramahaṁsa Parivrājakācārya Aṣṭottara-śata Śrī Śrīmad A. C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPĀDA Founder-Ācārya of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness 3 Set in The Brill and Futura Round Condensed display at The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust Africa © 2020 The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust Africa The copyrights for the offerings presented in this book remain with their respective authors. Quotes from books, lectures, letters and conversations by His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda © 2020 Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. Cover and artwork courtesy of The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust International, Inc. www.bbtafrica.co.za y www.bbt.org y www.krishna.com All Rights Reserved 3 CONTENTS Preface vii Acknowledgements ix THE MEANING OF VYĀSA-PŪJĀ 1 ŚRĪ GURVĀṢṬAKAM 5 Offerings by 4 SANNYĀSĪS 23 INITIATED DISCIPLES 39 GRANDDISCIPLES, GREAT-GRANDDISCIPLES & OTHER DEVOTEES 47 ISKCON CENTRES 277 THE BHAKTIVEDANTA BOOK TRUST 291 OTHER SOURCES 295 3 PREFACE 4 HEMANT BHAGA z THIS YEAR’S EDITION of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s reflect on one’s own life to understand the profound pan-African Vyāsa-pūjā book published effect of this mercy. -

Nowadays, the Meaning of Comedy Is Changed: Krushna Abhishek Krushna Abhishek Is Known for His Comic Roles in the films and TV

TM Volume 5 I Issue 08 I March 2020 I Film Review p27 John Abraham to produce well-known social entrepreneur Revathi Roy’s biopic p06 Social values and cinema p25 Nowadays, the meaning of Sanjay Dutt sets the bar high as the quintessential villain. Check the list! comedy is changed: p08 KRUSHNA ABHISHEK #BOLLYWOODTOWN CONTENTSCONTENTS ¡ Sanjay Dutt sets the bar high as the ¡ Karisma Kapoor along with ACE quintessential villain. Check the list! Business Awards to felicitate Achievers p08 p20 p34 Small Screen ¡ John Abraham to produce well-known social entrepreneur p30 Revathi Roy’s biopic Fashion & Lifestyle p06 ¡ "Now people are curious and they want to watch such films", Fatima Sana Shaikh spills beans on the shift in Bollywood p14 ¡ Social values and cinema p25 ¡ Himansh Kohli on break up with Neha Kakkar: She would cry on shows and people would blame me! p16 p10 Cover Story ¡ Film Review p27 From the publisher's desk Editor : Tarakant D. Dwivedi ‘Akela’ Editor-In-Chief : Yogesh Mishra Dear Readers, Sr. Columnist : Nabhkumar ‘Raju’ The month of February was an average month for many of the filmmakers. Spl. Correspondent : Dr. Amit Kr. Pandey (Delhi) Movies released in the month were- Shikara, Malang, Hacked, Love Aaj Kal, Graphic Designer : Punit Upadhyay Bhoot Part One: The Haunted Ship, Shubh Mangal Zyada Saavdhan, The Sr. Photographer : Raju Asrani Hundred Bucks, Thappad, Guns of Banaras, Doordarshan and O Pushpa I Hate Tears etc. COO : Pankaj Jain Hardly few of the movies did an average business on box office, rest of the Executive Advisor : Vivek Gautam movie could not do well on box office.