Mental Health Policy Implementation As an Integral Part of Primary Health Care Services in Oshana Region, Namibia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigating Factors Affecting the Financial

INVESTIGATING FACTORS AFFECTING THE FINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION DEGREE IN FINANCE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY PHILLEMON EPHRAIM 200211617 APRIL 2019 SUPERVISOR: DR FANNY SARUCHERA (NUST) i ABSTRACT Civil society organisations (CSOs) in developing countries like Namibia experience multiple operational hindrances, especially financial sustainability challenges that lead to the closure of their operations after few years leaving a void in many communities where they operate due to their dependency on foreign funding. Thus, there is need to establish the factors that affect the financial sustainability of these CSOs. The research sought to investigate the factors that affect financial sustainability of CSOs in Namibia. The target population of the research was 300 national CSOs in Namibia that depend on donor funding. The research sampled 80 CSOs and purposive sampling was used to select 1 employee in top management from each CSO giving a sample of 80 respondents. The research was based on primary data which was collected through a structured questionnaire. Content validity index (cvi) was used to establish whether the questionnaire measured what it was meant to measure and test-retest reliability was done where Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure reliability. Both descriptive and inferential statistics were used in analysis of the data. The research indicated and concluded that Income Diversification, Income Generation, Financial Management, Donor Relationship Management and Management Competence affected financial sustainability of CSOs in Namibia. The research further concluded that CSOs in Namibia are financially unsustainable. -

Human-Wildlife Conflict in Africa

ISSN 0258-6150 157 FAO FORESTRY PAPER 157 Human-wildlife conflict in Africa Causes, consequences Human-wildlife conflict in Africa – Causes, consequences and management strategies and management strategies FAO FAO Cover image: The crocodile is the animal responsible for the most human deaths in Africa Fondation IGF/N. Drunet (children bathing); D. Edderai (crocodile) FAO FORESTRY Human-wildlife PAPER conflict in Africa 157 Causes, consequences and management strategies F. Lamarque International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife (Fondation IGF) J. Anderson International Conservation Service (ICS) R. Fergusson Crocodile Conservation and Consulting M. Lagrange African Wildlife Management and Conservation (AWMC) Y. Osei-Owusu Conservation International L. Bakker World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)–The Netherlands FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2009 5IFEFTJHOBUJPOTFNQMPZFEBOEUIFQSFTFOUBUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPO QSPEVDUEPOPUJNQMZUIFFYQSFTTJPOPGBOZPQJOJPOXIBUTPFWFSPOUIFQBSU PGUIF'PPEBOE"HSJDVMUVSF0SHBOJ[BUJPOPGUIF6OJUFE/BUJPOT '"0 DPODFSOJOHUIF MFHBMPSEFWFMPQNFOUTUBUVTPGBOZDPVOUSZ UFSSJUPSZ DJUZPSBSFBPSPGJUTBVUIPSJUJFT PSDPODFSOJOHUIFEFMJNJUBUJPOPGJUTGSPOUJFSTPSCPVOEBSJFT5IFNFOUJPOPGTQFDJGJD DPNQBOJFTPSQSPEVDUTPGNBOVGBDUVSFST XIFUIFSPSOPUUIFTFIBWFCFFOQBUFOUFE EPFT OPUJNQMZUIBUUIFTFIBWFCFFOFOEPSTFEPSSFDPNNFOEFECZ'"0JOQSFGFSFODFUP PUIFSTPGBTJNJMBSOBUVSFUIBUBSFOPUNFOUJPOFE *4#/ "MMSJHIUTSFTFSWFE3FQSPEVDUJPOBOEEJTTFNJOBUJPOPGNBUFSJBMJOUIJTJOGPSNBUJPO QSPEVDUGPSFEVDBUJPOBMPSPUIFSOPODPNNFSDJBMQVSQPTFTBSFBVUIPSJ[FEXJUIPVU -

PISC ES Env Ir Onmental Serv Ices (Pt Y) Lt D Namparks Coastal National Parks Development Programme – Cape Cross Desalination Plant

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR A CONTAINERISED DESALINATION PLANT AT THE CAPE CROSS RESERVE MARINE ECOLOGY SPECIALIST ASSESSMENT Prepared for SLR Environmental Consulting (Namibia) (Pty) Ltd On behalf of Lund Consulting Engineers Prepared by Andrea Pulfrich September 2020 PISC ES Env ir onmental Serv ices (Pt y) Lt d NamParks Coastal National Parks Development Programme – Cape Cross Desalination Plant OWNERSHIP OF REPORTS AND COPYRIGHTS © 2020 Pisces Environmental Services (Pty) Ltd. All Rights Reserved. This document is the property of the author. The information, ideas and structure are subject to the copyright laws or statutes of South Africa and may not be reproduced in part or in whole, or disclosed to a third party, without prior written permission of the author. Copyright in all documents, drawings and records, whether produced manually or electronically, that form part of this report shall vest in Pisces Environmental Services (Pty) Ltd. None of the documents, drawings or records may be used or applied in any manner, nor may they be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means whatsoever for or to any other person, without the prior written consent of Pisces, except when they are reproduced for purposes of the report objectives as part of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) undertaken by SLR Environmental Consulting (Namibia) (Pty) Ltd. Andrea Pulfrich Pisces Environmental Services PO Box 302, McGregor 6708, South Africa, Tel: +27 21 782 9553 E-mail: [email protected] Website: -

Making the Invisible Visible | Generating Data on 'Slums'

Making the invisible visible Generating data on ‘slums’ at local, city and global scales Anni Beukes Working Paper Urban Keywords: December 2015 Urban poverty, enumeration, informal settlements, SDI About the author Anni Beukes, Shack/Slum Dwellers International (SDI), 4 Seymour Rd, Observatory 7925, Cape Town, South Africa. Email: [email protected] Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1, Matieland 7602, South Africa. Email: [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Human Settlements Group The Human Settlements Group works to reduce poverty and improve health and housing conditions in the urban centres of Africa, Asia and Latin America. It seeks to combine this with promoting good governance and more ecologically sustainable patterns of urban development and rural-urban linkages. Partner organisation Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI) www.sdinet.org SDI is a network of community-based organisations of the urban poor in 33 countries and hundreds of cities and towns across Africa, Asia and Latin America. In each country where SDI has a presence, affiliate organisations come together at the community, city and national level to form federations of the urban poor. Acknowledgements Much gratitude and appreciation to the all the data teams, federation leaders and support staff across the Shack/Slum Dwellers International network, whose patience, commitment and generosity with their time and knowledge, made the building of SDI’s Informal Settlement Knowledge Platform possible. Thank you to the data scientists and technologists who learned and unlearned with us. Thank you to all my colleagues at the SDI Secretariat for your support and indulgence. The biggest thank you, to Celine D’Cruz, who taught me to walk a settlement, sit down and listen, and then return to listen some more. -

Perceived Impact of Mass Media Campaigns on Hiv/Aids

PERCEIVED IMPACT OF MASS MEDIA CAMPAIGNS ON HIV/AIDS PREVENTION AMONG THE YOUTH IN OSHANA REGION, NORTHERN NAMIBIA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (INFORMATION STUDIES) IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES, DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION STUDIES DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY REGINA MPINGANA SHIKONGO APRIL 2010 Main Supervisor : Prof Kingo Mchombu, Department of Information and Communication Studies, University of Namibia Co-supervisor : Prof Agnes van Dyk, School of Nursing and Public Health, University of Namibia 1 ABSTRACT This study explores the perceived impact of mass media campaigns in communicating information on HIV/AIDS prevention to in-school (ISY) and out-of-school youth (OOSY) in Oshana Region, northern Namibia. Mass media campaigns have become one of the acknowledged means for stemming the rapid spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa. Since the first case of HIV/AIDS was diagnosed in Namibia in 1986, HIV/AIDS has become the number one cause of hospitalisation and death among people of all ages and of both sexes in the country. The mass media campaign organisations disseminate information through radio, television and printed materials based on the conventional health education model. Despite the high level of knowledge on HIV/AIDS which the youth were found to have, there is little change in their lifestyle and sexual behaviours and the HIV infections have continued at a high rate in the country. It is against this background that this study was conducted in Oshana Region, northern Namibia, one of the regions with a high HIV/AIDS infection rate in the country. -

Namibia Country Report BTI 2012

BTI 2012 | Namibia Country Report Status Index 1-10 6.99 # 32 of 128 Political Transformation 1-10 7.70 # 25 of 128 Economic Transformation 1-10 6.29 # 46 of 128 Management Index 1-10 6.03 # 31 of 128 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2012. The BTI is a global assessment of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economy as well as the quality of political management in 128 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2012 — Namibia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2012. © 2012 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2012 | Namibia 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 2.3 HDI 0.625 GDP p.c. $ 6474 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.8 HDI rank of 187 120 Gini Index - Life expectancy years 62 UN Education Index 0.617 Poverty3 % - Urban population % 38.0 Gender inequality2 0.466 Aid per capita $ 150.2 Sources: The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2011 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2011. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary Two decades after gaining independence, Namibia’s democratic and economic transformation continues to progress. As in former years, the presidential and parliamentary elections of 2009, as well as the regional elections of 2010, took place with a remarkable sense of political routine and met the standards of modern democratic elections, with the exception of an appeal due to alleged irregularities. -

Shiningayamwe2013.Pdf

i A CASE STUDY ON THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC EXPERIENCES OF THE CHILDREN OF THE LIBERATION STRUGGLE AT BERG AUKAS CAMP IN GROOTFONTEIN, OTJOZONDJUPA REGION A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS IN EDUCATION IN LIFELONG LEARNING AND COMMUNITY EDUCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY DORTHEA NANGHALI ETUWETE SHININGAYAMWE STUDENT NUMBER: 200218794 APRIL 2013 MAIN SUPERVISOR: DR.R K SHALYEFU CO-SUPERVISOR: DR AT.KANYIMBA i ABSTRACT In 1990, when Namibia gained independence, about 43000 exiled Namibians were repatriated back home from different countries. Included in this number were soldiers and refugees including children who were born during the liberation struggle. These children have been called “Exiled Kids,” “Returnees Children,” Ex-War Children,” SWAPO Children” and so on. However, later on they were officially called Children of the Liberation Struggle (CLS) after they had come to prominence in the country through widespread demonstrations, demanding that the government provide them with jobs, better educational opportunities, national identity documents and vocational training. There is little documentation in the literature relating to the social and economic experiences of the CLS. Therefore this research addresses this lacuna. The study applied qualitative research methods; with a mixed research design employing; narrative research and case studies. Data was collected by means of in-depth interviews with twelve (three males and nine females) CLS residing at Berg Aukas. A voice recorder was used to record the interviews with participants. The study found that the CLS grew up in children’s homes/shelters; they had never stayed with their biological parents, some had been brought up by their grandparents and after their death the CLS remained on their own, looking for family members, love, a sense of belonging and for a place they could call home. -

The Tangled Lives of Philip Wetu a Namibian Story About Life Choices and HIV

The Tangled Lives of Philip Wetu A Namibian story about life choices and HIV A publication in the German Health Practice Collection Published by: German Health Practice Collection Showcasing health and social protection for development Goal The German Health Practice Collection (GHPC) aims to share good practices and lessons learned from health and social protection projects around the world. Since 2004, the Collection has helped assemble a vibrant community of practice among health experts, for health.bmz.de/good-practices whom the process for each publication is as important www as the publication itself as it is set up to generate a @HealthyDEvs number of learning opportunities: The community works together to define good practice, which is then criti- fb.com/HealthyDEvs cally discussed within the community and assessed by independent peer reviewers. Scope The Collection is drawn from projects, programmes and initiatives supported by German Development Co- operation (GDC) and its international and country-level partners around the world. GDC includes the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and its implementing organisations: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and KfW Development Bank (KfW). The projects are drawn from a wide range of technical fields and geographi- cal areas, at scales running from the local to the global. The common factor is that they make useful contribu- tions to the current state of knowledge about health and social protection in development settings. Publications All publications in the Collection describe the projects in Join the Community of Practice enough detail to allow for their replication or adaptation Do you know of promising practices in German-supported in different contexts. -

Assessing Potential Impacts of Trade in Trophies Imported for Hunting Purposes to the EU-27 on Conservation Status of Annex B Species

Assessing potential impacts of trade in trophies imported for hunting purposes to the EU-27 on conservation status of Annex B species Part 2: Discussion and Case studies (Version edited for public release) Prepared for the European Commission Directorate General Environment Directorate E - Global & Regional Challenges, LIFE ENV.E.2 - Global Sustainability, Trade & Multilateral Agreements by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre August, 2013 UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road PREPARED FOR Cambridge The European Commission, Brussels, Belgium CB3 0DL United Kingdom DISCLAIMER Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314 The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136 the views or policies of UNEP, contributory Email: [email protected] organisations or editors. The designations Website: www.unep-wcmc.org employed and the presentations do not imply the The United Nations Environment Programme expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part World Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP- of UNEP, the European Commission or WCMC) is the specialist biodiversity assessment contributory organisations, editors or publishers centre of the United Nations Environment concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Programme (UNEP), the world’s foremost city area or its authorities, or concerning the intergovernmental environmental organisation. delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The The Centre has been in operation for over 30 years, mention of a commercial entity or product in this combining scientific research with practical policy publication does not imply endorsement by UNEP. advice. The Centre's mission is to evaluate and highlight the many values of biodiversity and put © Copyright: 2013, European Commission authoritative biodiversity knowledge at the centre of decision-making. -

Children and AIDS Third Stocktaking Report, 2008 Children and AIDS: Third Stocktaking Report, 2008

Children and AIDS Third Stocktaking Report, 2008 Children and AIDS: Third Stocktaking Report, 2008 Cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ06-2216/Giacomo Pirozzi; back cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ06-2212/Giacomo Pirozzi. The paintings on the covers of this report are by children at the Maputo Day Hospital, Mozambique, a facility providing medicine and psychosocial support, including counselling and antiretroviral therapy, to children living with HIV. UNAIDS, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, brings together the efforts and resources of 10 UN system organizations to the global AIDS response. Co-sponsors include UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, UNDP, UNFPA, UNODC, ILO, UNESCO, WHO and the World Bank. Based in Geneva, the UNAIDS secretariat works on the ground in more than 75 countries worldwide. Figures 1 and 2 on pages 4 and 5 of this report have been corrected; the figures remain uncorrected in the summary version that was issued in advance of this report. For additional updates subsequent to the issue of this report, please visit the UNICEF website and www.unicef.org/publications. Page 2 Introduction contents Page 4 1. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV Page 10 2. Providing paediatric treatment and care Page 16 3. Preventing infection among adolescents and young people Page 21 4. Protection and care for children affected by AIDS Page 26 Conclusions Page 29 References Page 32 Annex: Notes on the data Page 33 Goal 1. Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV in low- and middle-income countries Page 36 Goal 2. Providing paediatric treatment in low- and middle-income countries Page 39 Goal 3. -

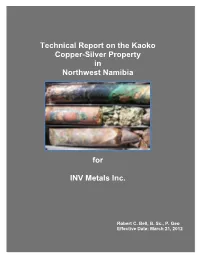

Technical Report on the Kaoko Copper-Silver Property in Northwest Namibia

Technical Report on the Kaoko Copper-Silver Property in Northwest Namibia for INV Metals Inc. Robert C. Bell, B. Sc., P. Geo Effective Date: March 21, 2012 Table of Contents 1. SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... 9 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 10 2.1. TERMS OF REFERENCE .............................................................................................. 10 2.2. SOURCES OF INFORMATION ..................................................................................... 10 2.3. UNITS OF MEASURE ..................................................................................................... 11 3. RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS .......................................................................................... 11 4. PROPERTY LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION ...................................................................... 11 4.1. PROPERTY LOCATION ................................................................................................. 11 Figure 4-1: Location Map of Namibia and Kaoko .................................................................. 12 Figure 4-2: Location Map of Kaoko Property ......................................................................... 12 4.2. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION .......................................................................................... 13 Table 4-1: Property -

PANTHERA PARDUS) in AFRICA (Prepared by the Secretariat)

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 5th Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC5) Online, 28 June – 9 July 2021 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC5/Doc.6.3.1.3/Rev.1 CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE LEOPARD (PANTHERA PARDUS) IN AFRICA (Prepared by the Secretariat) Summary: On the basis of CMS Decision 13.97 Conservation and Management of the Leopard (Panthera pardus) in Africa, the Sessional Committee is requested to review the Roadmap for the Conservation of Leopards in Africa, and formulate recommendations as appropriate for consideration by the Range States, IUCN and others, as needed. This document is accompanied by one Annex: Roadmap for the Conservation of the Leopard in Africa. UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC5/Doc.6.3.1.3/Rev.1 CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE LEOPARD (PANTHERA PARDUS) IN AFRICA Background 1. CMS Decision 13.97 Conservation and Management of the Leopard (Panthera pardus) in Africa and directed to the Scientific Council provides: The Scientific Council shall review the Roadmap for the Conservation of Leopards in Africa contained in UNEP/CMS/COP13 Doc.26.3.1/Annex 4, and formulate recommendations as appropriate for consideration by the Range States, IUCN and others, as needed. History of the Roadmap for the Conservation of Leopards in Africa 2. The conservation of Leopard has received international attention for a long time. The Leopard has been listed on Appendix I of CITES since 1975, regulating the trade of its skins or products. Since then, a series of decisions regarding Leopard skin trade has been adopted under CITES.