Acronym Absurdity Constrains Psychological Science Moin Syed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

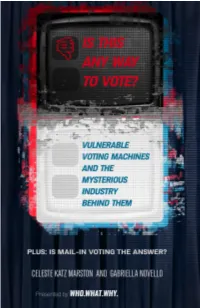

Is This Any Way to Vote?

IS THIS ANY WAY TO VOTE? Vulnerable Voting Machines and the Mysterious Industry Behind Them CELESTE KATZ MARSTON AND GABRIELLA NOVELLO WhoWhatWhy New York City Copyright © 2020 by WhoWhatWhy All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Cover design by Cari Schmoock. Cover art and photo editing by Michael Samuels. Data visualizations by Lizzy Alves. Published in the United States by WhoWhatWhy. eBook ISBN 978-1-7329219-1-7 WhoWhatWhy® is a registered trademark of Real News Project, Inc. CONTENTS Initialisms and Acronyms Used in This Book vi Introduction 1 1. The Voting-Machine Manufacturers 5 2. The Voting Machines 25 3. Voting Machine Accessibility 42 4. Voting Machine Vulnerabilities 55 5. Solutions and Global Perspectives 77 6. Conclusion 102 7. Addendum: Is Mail-in Voting the Answer? 108 About the Authors 116 About WhoWhatWhy 118 Glossary 119 INITIALISMS AND ACRONYMS USED IN THIS BOOK ADA Americans with Disabilities Act BMD ballot-marking device COIB Conflicts of Interest Board DRE direct-recording electronic machine EAC Election Assistance Commission EMS election management system ES&S Election Systems & Software FVAP Federal Voting Assistance Program FWAB Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot HAVA Help America Vote Act MPSA Military Postal System Agency NPRM notice of proposed rulemaking OSET Open Source Election Technology Institute RFP request for proposal RLA risk-limiting audit SQL Structure Query Language TGDC Technical Guidelines Development Committee UOCAVA Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act VSAP Voting Solutions for All People VVPAT Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail VVSG Voluntary Voting System Guidelines Photo credit: Florida Memory / Flickr 2 | INTRODUCTION When we talk about elections, we often focus on the campaign horserace, who is up or down in the polls, the back and forth between candidates, and maybe a little about which issues matter most to voters. -

President Trump's Crusade Against the Transgender Community

American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law Volume 27 Issue 4 Article 2 2019 President Trump's Crusade Against the Transgender Community Brendan Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/jgspl Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Law and Gender Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Williams, Brendan (2019) "President Trump's Crusade Against the Transgender Community," American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law: Vol. 27 : Iss. 4 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/jgspl/vol27/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Williams: President Trump's Crusade Against the Transgender Community PRESIDENT TRUMP'S CRUSADE AGAINST THE TRANSGENDER COMMUNITY BRENDAN WILLIAMS* Introdu ction ...................................................................................... 52 5 I. Trump's Attacks on the Transgender Community ........................ 528 II. Transgender Rights in the Federal Courts .................................... 533 III. State-Level Activity on Transgender Rights .............................. 540 C on clu sion ........................................................................................ 54 5 INTRODUCTION In his dystopian speech during the 2016 Republican National Convention, Donald Trump accepted the Republican nomination and "[v]owed 'to do everything in my power to protect our L.G.B.T.Q. -

Linkedin Marketing: an Hour a Day Acknowledgments About the Author

Table of Contents Cover Praise for LinkedIn Marketing: An Hour a Day Acknowledgments About the Author Foreword Introduction Chapter 1: Get LinkedIn Social Marketing Is Marketing Understanding LinkedIn Using LinkedIn The Future of LinkedIn Chapter 2: Weeks 1–2: Get Started on LinkedIn Week 1: Prepare Your LinkedIn Presence Week 2: Define Goals and Join LinkedIn Chapter 3: Weeks 3–6: Ready, Set, Profile Week 3: Nifty Tools and Ninja Tricks for Creating Your Keyword List Week 4: Optimize Your Profile and Be Findable Week 5: Customize Your Profile to Stand Out in the Crowd Week 6: Utilizing Extra Real Estate Chapter 4: Weeks 7–9: Use Your Company Profile for Branding and Positioning Week 7: Creating a Company Profile Week 8: Adding Products and Services Week 9: Company Updates, Analytics, and Job Postings—Yours and Others Chapter 5: Weeks 10–15: Creating and Managing a Network That Works Week 10: Using LinkedIn’s Add Connections Tool Week 11: Connecting to Strategic Contacts Week 12: Using LinkedIn’s People You May Know Feature Week 13: Managing Your Network Week 14: Monitoring Your Network Week 15: Giving and Getting Recommendations from Your Network Chapter 6: Weeks 16–18: Getting Strategic with Groups Week 16: Building Your Network with Strategic Groups Week 17: Creating Relationships with Groups Week 18: Creating Your Own Group Chapter 7: Weeks 19–22: Get Strategic with LinkedIn’s “Other” Options Week 19: Using LinkedIn Answers Week 20: Using LinkedIn Events Week 21: Sharing with Applications Week 22: Exploring Industry-Based and LinkedIn -

Roles of Linked Fate and Black Political Knowledge In

Roles of Linked Fate and Black Political Knowledge in Shaping Black Responses to Group Messages Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brianna Nicole Mack Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2018 Dissertation Committee Kathleen McGraw, Advisor Thomas Nelson, Co-Advisor Nathaniel Swigger Ismail K. White 1 Copyrighted by Brianna Nicole Mack 2018 2 Abstract This dissertation explores the relationship between linked fate, political knowledge and message cues. I argue there is a relationship between Black political knowledge, linked fate, and attitudes that varies based on the salience of the issue in question, the source of the message, tone of the message and the recipient’s strength of linked fate and amount of Black political knowledge they possessed. This argument draws on research on political attitudes, political knowledge, and psycho-political behavior within the Black community. I conceptualize Black political knowledge as the range of factual information about Black racial group’s role in and relationship with the American political system stored in one’s memory. Afterwards I introduce the Black political knowledge battery, a 14-item measurement of said concept with questions about the historical, policy, and partisanship aspects of the racial group’s political behavior. Afterwards, I use the battery in a survey experiment to examine the relationship between issue salience, message cues, linked fate and Black political knowledge. The data analysis chapter determined support for as well as rejection of the theoretical framework, albeit aspects of the model. -

Branding and the Democratic Party: a Design Methodology Case Study

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2004 Branding and the Democratic Party: a design methodology case study Lara Fredrickson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Fredrickson, Lara, "Branding and the Democratic Party: a design methodology case study" (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 20417. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/20417 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Branding and the Democratic Party: A design methodology case study by Lara Fredrickson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS Major: Graphic Design Program of Study Committee: Roger Baer, Major Professor Debra Satterfield Marcia Prior-Miller Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 ii Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Lara Fredrickson has met the requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES vi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 What is the Status of the Democratic Party? 2 Visual representation -

Virtual Classroom Newsletter for English Teachers Looking Ahead To

January 2008 About the USA – Virtual Classroom Newsletter for English Teachers In this issue: New Year’s Resolutions | Teaching Literature: Words | This Month: Religious Freedom Day and Martin Luther King, Jr. Day| NEW eJournal: New Media Making Change | Web Chat Station | Education USA Looking Ahead to 2008 The earliest reliable records of resolutions are in New Year’s Resolutions Roman writings from around 180 A.D., says anthropologist Douglas Raybeck of Hamilton College. Planning ahead and trying to change It's that time of year again when many people resolve to improve their things is uniquely human, he explains. Romans lives. Have you started making your 2008 resolutions yet? A promise wanted to get along better with neighbors, help that you make to yourself to start doing something good or stop doing the poor and improve their bodies. (Sound something bad on the first day of the year: lose weight, pay off debts, familiar?) There are no records, however, about save money, get a better job, get fit, eat right, get a better education, the strength of Roman “will power” and how they drink less alcohol, quit smoking, reduce stress, take a trip, or volunteer measured up to their resolutions. Source: to help others. Look for the most popular New Years Resolutions at the National Public Radio (NPR) USA.gov Home Page. Links o About.com: Top 10 New Year's Resolutions o American Academy of Pediatrics: 20 Healthy New Year’s Resolutions for Kids o The Independent: 10 Green New Year's Resolutions o NPR: Reflections on the New Year: Commentator and philosopher Alain de Botton argues in favor of New Year's resolutions. -

An Article Summarizing Their Findings in Regius Magazine

1 WHAT HISPANICS SAID ABOUT BIDEN In Spanish AND TRUMP and on Twitter By Michael Cornfield, The Graduate School of Political Management Carolina Fuentes, and The George Washington University Meagan O’Neill The “Hispanic” or “Latino” Vote (the terms will be which issue appeals and personal characterizations used interchangeably here) became news after the resonated among Spanish speakers. What does the 2020 presidential election. That’s because it changed message pattern tell us about Hispanic involvement from 2016 and made a difference in two key states. in American politics at the presidential level? Our Definitive data breaking down the vote has yet to findings support the idea that campaigning on the arrive, and exit poll data compiled on election day has notion that a uniform “Hispanic” or “Latino” voting raised methodological concerns due to the pandemic bloc exists across the nation makes less sense with and the correspondingly heavy voting which occurred each succeeding campaign and election cycle. before election day. But it is clear that Hispanic votes were decisive in Arizona, which went Democratic at the presidential level for the first time in 24 years, and The Conversational Agenda Florida, where strong Trump showings in Miami-Dade Spanish-language tweeters talking about Biden and and Osceola Counties helped put the Sunshine State Trump addressed a variety of issues. As the table in the Republican column. There were also striking below shows, tweets with Trump’s name outnumbered developments in Nevada, with record turnouts by those with Biden’s name by a 2 to1 margin. That’s Hispanics, and Texas, where Trump posted big gains not surprising given the president’s constant and in Harris County (Houston) and along the Mexican prominent presence on Twitter. -

Democracy Lost: a Report on the Fatally Flawed 2016 Democratic Primaries

Democracy Lost: A Report on the Fatally Flawed 2016 Democratic Primaries Election Justice USA | ElectionJusticeUSA.org | [email protected] Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL ....................................................................................................... 3 A. ABOUT ELECTION JUSTICE USA .............................................................................................. 3 B. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................................................. 3 C. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 4 II. SUMMARY OF DIRECT EVIDENCE FOR ELECTION FRAUD, VOTER SUPPRESSION, AND OTHER IRREGULARITIES ...................................................................................................... 9 A. VOTER SUPPRESSION ................................................................................................................. 9 B. REGISTRATION TAMPERING ................................................................................................... 10 C. ILLEGAL VOTER PURGING ...................................................................................................... 10 D. EVIDENCE OF FRAUDULENT OR ERRONEOUS VOTING MACHINE TALLIES ............... 11 E. MISCELLANEOUS ........................................................................................................................ 11 F. ESTIMATE OF PLEDGED DELEGATES AFFECTED .............................................................. -

An Interaction Approach Between Services for Extracting Relevant Data from Tweets Corpora

EPiC Series in Language and Linguistics Volume 1, 2016, Pages 97{110 CILC2016. 8th International Conference on Corpus Linguistics An interaction approach between services for extracting relevant data from Tweets corpora Mehdy Dref1 and Anna Pappa2 1 LIASD, Universit´eParis 8, Saint-Denis, France [email protected] 2 LIASD, Universit´eParis 8, Saint-Denis, France [email protected] Abstract We present a system based on the need of special infrastructure adequate to software agents to operate, to compose and make sense from the contents of the Web resources through the development of a multi-agent system oriented services interactions. Our method follows the different construction ontology techniques and updates them by extracting new terms and integrate them to the ontology.It is based on the detection phrases via the ontological database DBPedia. The system treats each syntagme extracted from the corpus of messages and verifies whether it is possible to associate them directly to a DBPedia knowledge. In case of failure, these service agents interact with each other in order to find the best possible answer to the problem, by operating directly in the phrase, trying to semantically modify it, until the association with ontological knowledge becomes possible. The advantage of our approach is its modularity : it is both possible to add / modify / delete a service or define a new one, and then influence the outcome product. We could compare the results extracted from a heterogeneous body of messages from the Twitter social network with Tagme method, based mainly on storage and annotation of encyclopaedic corpus. -

TRUTH on the BALLOT Fraudulent News, the Midterm Elections, and Prospects for 2020

TRUTH ON THE BALLOT Fraudulent News, the Midterm Elections, and Prospects for 2020 pen.org TRUTH ON THE BALLOT Fraudulent News, the Midterm Elections, and Prospects for 2020 March 13, 2019 ©2019 PEN America. All rights reserved. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and hu- man rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible. Founded in 1922, PEN America is the largest of more than 100 centers of PEN International. Our strength is in our membership—a nationwide community of more than 7,000 novelists, journalists, poets, es- sayists, playwrights, editors, publishers, translators, agents, and other writing professionals. For more information, visit pen.org. Design by Pettypiece + Co. Cover image: Ligorano/Reese's installation of a 2000 pound ice sculpture called "Truth Be Told" in front of the U.S. Capitol to protest "fake news" in the U.S. (September 21, 2018). Photograph by Sue Abramson. This report was generously funded by CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Efforts to Combat Fraudulent News 4 Fraudulent News in the 2018 Election Cycle 6 Conclusions and Recommendations 7 INTRODUCTION 8 Overview 9 Why Fraudulent News Is a Free Expression Issue 10 FIGHTING FRAUDULENT NEWS 11 Tech Companies 12 Facebook 13 Twitter 20 Google and YouTube 24 Making Political Ads More Transparent 26 Ad Archives 29 -

Case 2:81-Cv-03876-JMV-JBC Document 138 Filed 11/05/16 Page

Case 2:81-cv-03876-JMV-JBC Document 138 Filed 11/05/16 Page 1 of 36 PageID: <pageID> UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY Not for Publication DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE, et al., Civil Action No. 81-03876 Plaintiffs, OPINION v. REPUBLICAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE, et al., Defendants. John Michael Vazquez, U.S.D.J. Plaintiff Democratic National Committee (“DNC”) alleges that Defendant Republican National Committee (“RNC”) violated a consent decree (“Consent Decree” or “Decree”) between the parties. The Consent Decree was originally entered in 1982 and was subsequently modified in 1987 and 2009. The RNC denies that it is in violation of the Decree. The DNC seeks the following relief: a finding that the RNC is in contempt, enforcement of the Consent Decree with sanctions, injunctive relief, and an extension of the Consent Decree. For the reasons that follow, the Court denies the DNC’s motions for injunctive relief, for contempt, and for sanctions. The Court denies, at this time, the DNC’s request to extend the Consent Decree, but the Court will hear the parties after Election Day as to additional discovery on this point in order to develop a full record to determine whether an extension is warranted. Case 2:81-cv-03876-JMV-JBC Document 138 Filed 11/05/16 Page 2 of 36 PageID: <pageID> This opinion will first review the current posture of this matter before turning to the background of the Consent Decree and the positions of the parties. The Court will then analyze the DNC and RNC’s arguments in light of the Decree and the applicable law. -

The Othering of Donald Trump and His Supporters Stephen D

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Communications Faculty Research Communications Spring 3-14-2018 The Othering of Donald Trump and His Supporters Stephen D. Cooper Ph.D. Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/communications_faculty Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Stephen D. “The Othering of Donald Trump and His Supporters.” The 2016 American Presidential Campaign and the News: Implications for American Democracy and the Republic. Ed. Jim A. Kuypers. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018. 31-54. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Communications at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communications Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EDITED BY JIM A. KUYPERS THE 2016 AMERICAN PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN AND THE NEWS In1 plica tions for A1nerican De 1n ocracy and the Republic Chapter Three The Othering of Donald Trump and His Supporters Stephen D. Cooper The 2016 presidential election was extraordinary in many respects. One was the way in which the Republican candidate and his supporters were dispar aged in the establishment press. Although it is a truism that politics can often be rough (as in the sayings, 'It ain't beanbag" and "It s a contact sport' ) and any apparent civility in the rhetoric is often just a mask in front of bare knuckle tactics, many observers have noted that the 2016 election became especially rough.