The Associated Press Decision: an Extension of the Sherman Act?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's G8 Plans

Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, 2010 Jenilee Guebert Director of Research, G8 Research Group, with Robin Lennox and other members of the G8 Research Group June 7, 2010 Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, Ministerial Meetings 31 2010 1 G7 Finance Ministers 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms 2 G20 Finance Ministers 37 Preface 2 G8 Foreign Ministers 37 Introduction: Canada’s 2010 G8 2 G8 Development Ministers 41 Agenda: The Policy Summit 3 Civil Society 43 Priority Themes 3 Celebrity Diplomacy 43 World Economy 5 Activities 44 Climate Change 6 Nongovernmental Organizations 46 Biodiversity 6 Canada’s G8 Team 48 Energy 7 Participating Leaders 48 Iran 8 G8 Leaders 48 North Korea 9 Canada 48 Nonproliferation 10 France 48 Fragile and Vulnerable States 11 United States 49 Africa 12 United Kingdom 49 Economy 13 Russia 49 Development 13 Germany 49 Peace Support 14 Japan 50 Health 15 Italy 50 Crime 20 Appendices 50 Terrorism 20 Appendix A: Commitments Due in 2010 50 Outreach and Expansion 21 Appendix B: Facts About Deerhurst 56 Accountability Mechanism 22 Preparations 22 Process: The Physical Summit 23 Site: Location Reaction 26 Security 28 Economic Benefits and Costs 29 Benefits 29 Costs 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms AU African Union CCS carbon capture and storage CEIF Clean Energy Investment Framework CSLF Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum DAC Development Assistance Committee (of the Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development) FATF Financial Action Task Force HAP Heiligendamm L’Aquila Process HIPC heavily -

Presentation (Pdf)

Presentation of the Stars4Media Initiative EURAGORA EURAGORA is an exclusive project of EFE (Spanish news agency) and LUSA (Portuguese news agency). The operational team was constituted by three people from each agency (one editorial, one commercial&marketing, and one multimedia), supported by another 10 mentors, including the directors and the national correspondents in both countries. Team’s Both agencies decided to choose young or relatively junior professionals, with different backgrounds and skills, to lead presentation the three mini-teams. Gender equality was taken into account – in fact, there were more women than men on the lead. The multidisciplinary approach was the added value of this common project. Both agencies decided to subdivide the team in three smaller groups – one for editorial aspects, another for commercial&marketing, and a third for technical aspects. Initiative’s summary EURAGORA is a project of Iberian nature with European scope, that designed a model of cross-border virtual debates on topics of broader interest. The subject chosen for the pilot debate was “Tourism in times of covid-19”, subdivided in two topics: "Security, what do consumers expect, how do industry, governments, the European Union respond?” and "Reinvention and opportunities: sun and beach / urban and cultural / rural tourism". This choice resulted from the huge impact this pandemic is having in Tourism globally, but especially in both Spain and Portugal, as countries much dependent on that economic sector. The Spanish and Portuguese government responsible for Tourism, the European commissioner with responsibility for the Internal Market (and Tourism), Thierry Breton and the European commissioner Elisa Ferreira were speakers in the debates, among almost 20 participants, representing international organizations, European institutions, national governments, regional and local authorities, enterprises, and civil society. -

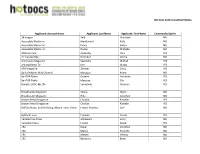

Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media Applicant: Account Name Applicant: Last Name Applicant: First Name Community Opt-In 24 Images

Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media Applicant: Account Name Applicant: Last Name Applicant: First Name Community Opt-In 24 images Selb Charlotte NO Accessible Media Inc. MacDonald Kelly NO Accessible Media Inc. Evans Simon NO Accessible Media Inc. Dudas Michelle NO Afisharu.com Zaslavsky Nina YES Air Canada Rep González Leticia NO Alternavox Magazine Saavedra Mikhail YES Arirang Korea TV Kim Mingu YES ATK Magazine Zimmer Cindy YES Balita/Filipino Web Channel Marquez Romy NO BanTOR Radio Qorane Nuruddin YES BanTOR Radio Mazzuca Ola YES Braidio, CKDU 88.1fm Simmonds Veronica YES Broadcaster Magazine Shane Myles NO Broadcaster Magazine Hiltz Jonathan NO Broken Pencil Magazine Charkot Richelle YES Broken Pencil Magazine Charkot Richelle YES Buffalo News, Buffalo Rising, Albany Times Union Francis Penders Carl NO ByBlacks.com Franklin Nicole YES Canada Free Press Anklewicz Larry NO Canadian Press Friend David YES CBC Dekel Jonathan NO CBC Mattar Pacinthe NO CBC Mesley Wendy NO CBC Bambury Brent NO Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media CBC Tremonti Anna Maria NO CBC Galloway Matt NO CBC Pacheco Debbie NO CBC Berry Sujata NO CBC Deacon Gillian NO CBC Rundle Lisa NO CBC Kabango Shadrach NO CBC Berube Chris YES CBC Callender Tyrone YES CBC Siddiqui Tabassum NO CBC Mitton Peter YES CBC Parris Amanda YES CBC Reid Tashauna NO CBC Hosein Lise NO CBC Sumanac-Johnson Deana NO CBC Knegt Peter YES CBC Thompson Laura NO CBC Matlow Rachel NO CBC Coulton Brian NO CBC Hopton Alice NO CBC Cochran Cate YES CBC - Out in the Open Guillemette Daniel NO CBC / TVO Chattopadhyay Piya NO CBC Arts Candido Romeo YES CBC MUSIC FRENETTE BRAD NO CBC MUSIC Cowie Del NO CBC Radio Nazareth Errol NO CBC Radio Wachtel Eleanor NO Channel Zero Inc. -

Who Set the Narrative? Assessing the Influence of Chinese Media in News Coverage of COVID-19 in 30 African Countries the Size Of

Who Set the Narrative? Assessing the Influence of Chinese Media in News Coverage of COVID-19 in 30 African Countries The size of China’s State-owned media’s operations in Africa has grown significantly since the early 2000s. Previous research on the impact of increased Sino-African mediated engagements has been inconclusive. Some researchers hold that public opinion towards China in African nations has been improving because of the increased media presence. Others argue that the impact is rather limited, particularly when it comes to affecting how African media cover China- related stories. This paper seeks to contribute to this debate by exploring the extent to which news media in 30 African countries relied on Chinese news sources to cover China and the COVID-19 outbreak during the first half of 2020. By computationally analyzing a corpus of 500,000 news stories, I show that, compared to other major global players (e.g. Reuters, AFP), content distributed by Chinese media (e.g. Xinhua, China Daily, People’s Daily) is much less likely to be used by African news organizations, both in English and French speaking countries. The analysis also reveals a gap in the prevailing themes in Chinese and African media’s coverage of the pandemic. The implications of these findings for the sub-field of Sino-African media relations, and the study of global news flows is discussed. Keywords: China-Africa, Xinhua, news agencies, computational text analysis, big data, intermedia agenda setting Beginning in the mid-2010s, Chinese media began to substantially increase their presence in many African countries, as part of China’s ambitious going out strategy that covered a myriad of economic activities, including entertainment, telecommunications and news content (Keane, 2016). -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1999, No.36

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Forced/slave labor compensation negotiations — page 2. •A look at student life in the capital of Ukraine — page 4. • Canada’s professionals/businesspersons convene — pages 10-13. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVII HE No.KRAINIAN 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1999 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine U.S.T continues aidU to Kharkiv region W Pustovoitenko meets in Moscow with $16.5 million medical shipment by Roman Woronowycz the region and improve the life of Kharkiv’s withby RomanRussia’s Woronowycz new increasingprime Ukrainian minister debt for Russian oil Kyiv Press Bureau residents, which until now had produced Kyiv Press Bureau and gas. The disagreements have cen- few tangible results. tered on the method of payment and the KYIV – The United States government “This is the first real investment in terms KYIV – Ukraine’s Prime Minister amount. continued to expand its involvement in the of money,” said Olha Myrtsal, an informa- Valerii Pustovoitenko flew to Moscow on Ukraine has stated that it owes $1 bil- Kharkiv region of Ukraine on August 25 tion officer at the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv. August 27 to meet with the latest Russian lion, while Russia claims that the costs when it delivered $16.5 million in medical Sponsored by the Department of State, the prime minister, Vladimir Putin, and to should include money owed by private equipment and medicines to the area’s hos- humanitarian assistance program called discuss current relations and, more Ukrainian enterprises, which raises the pitals and clinics. -

A Guide for Writers and Editors Toronto: the Canadian Press 1983

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Canadian Journal of Communication (CJC) CANADIAN JOURNAL OF COMMUNICATION, 1984, -10 (3), 83 - 92. REVIEW ESSAY Bob Taylor, Editor C. P. Stylebook: A Guide for Writers and Editors Toronto: The Canadian Press 1983. $ 10.00 Reviewed by: N. Russell School of Journalism and Communications University of Regina Does the seemingly innocuous Canadian Press Stylebook wield much influence on general writ- ing style in Canada? And if -- as this writer contends -- it does, how can such influence be measured and, if necessary, contained? The questions are provoked by the recent publication of a new edition of the Stylebook, who1 ly revised and revamped. Overnight , the little blue (1966 and 1968 editions) or green (1974 and 1978) staff manual has expanded to a fat, fancy production with a $ 10.00 price tag. My own first exposure to the CP bible came when I joined the agency as a reporter in the Halifax bureau, in 1960. The 120-page manual that I was told to memorize contained a lot of mundane instruct ions on f i 1 ing wire-copy via teletype, some f i 1lers on the history of the agency and some rules on CP copy style. To a high school drop-out, many of these were useful and en1 ightening , 1ike the difference between "career" and "careen" (which the rest of the world still persists in ignoring). Some, even then, were archaic or arcane. For instance, peremptorily listed as "Under the Ban" were "chorine", "diesel ized ", natator", and "temblor" -- words that I had never encountered and which in the intervening decades I have never, ever felt any inclination to use. -

Deutsche Presse-Agetur

d e u t s c h e p r e s s e – a g e n t u r ( d p a ) E LECTRONIC R ESOURCE P RESERVATION AND A CCESS N ETWORK www.erpanet.org ERPANET – Electronic Resource Preservation and Access Network – is an activity funded by the European Commission under its IST programme (IST-2001-3.1.2). The Swiss Federal Government provides additional funding. Further information on ERPANET and access to its other products is available at http://www.erpanet.org. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). ISSN 1741-8682 © ERPANET 2004 E LECTRONIC R ESOURCE P RESERVATION AND A CCESS N ETWORK Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa) Case Study Report 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................2 Chapter 1: The ERPANET Project...........................................................................................3 Chapter 2: Scope of the Case Studies ...................................................................................4 Chapter 3: Method of Working ................................................................................................6 Chapter 4: The Deutsche Presse-Agentur (dpa) ...................................................................7 Chapter 5: Circumstances of the Interviews .........................................................................8 Chapter 6: Analysis..................................................................................................................9 -

Agence France Presse (AFP) Transforms Global Editorial System

in collaboration with The successful implementation of the Iris system for text and multimedia journalists is “undoubtedly due to the depth of the relationship established between the Capgemini and AFP teams.” Philippe Sensi Deputy Director of IT Systems Agence France-Presse Agence France Presse (AFP) Transforms Global Editorial System Capgemini delivers The Situation the first stage of a Leading global news agency Agence France Presse (AFP) had an editorial management system that consisted of content silos, built up over time as project to overhaul it expanded its editorial services to include text, photos, graphics, video and multimedia. The agency wanted to deliver a new system for all its AFP’s global editorial journalists that would: • Provide a homogeneous multimedia and multilingual system that no system: a true longer separates access from content according to media type but instead: transformation – aligns each work tool to corresponding data type – standardizes the metadata of documents, regardless of the format program – facilitates the access and sharing of content between different editorial departments and creates a holistic view of the agency’s services – provides a system that is easy to use; available 24/7; highly scalable and easy to upgrade • Better manage the different steps of producing content, while creating an intuitive interface to make it easier for journalists to collaborate • Centralize data and thereby reduce operational and maintenance costs. Telecom, Media & Entertainment the way we do it About Capgemini The Background With more than 130,000 people in Rising demand for multimedia content and the advent of mobility are 44 countries, Capgemini is one of the world’s foremost providers of among the factors that make efficient and flexible data management consulting, technology and systems increasingly crucial for a global news agency. -

Media Relations and Event Management (Mrem) Services

MEDIA RELATIONS AND EVENT MANAGEMENT MALAYSIAN (MREM) NATIONAL SERVICES NEWS AGENCY (BERNAMA) Table of Contents 1. INRODUCTION 1.1 About the Malaysian National News Agency (BERNAMA) 3 1.2 About Media Relations And Event Management (MREM) 3 2. MEDIA RELATIONS AND EVENT MANAGEMENT (MREM) FEATURES 4 3. BENEFITS TO MREM USERS 4 4. MREM SERVICES 4.1 Press Release Distribution For Domestic (Malaysia & Singapore) 5 4.2 ASIANET Service 6 4.3 Translation Services 7 4.4 Media Relations Services 7 4.5 Event Management 8 4.5.1 Publicity & Promotion 8 4.5.2 Media Centre Management 8 2 1.0 Introduction 1.1 About the Malaysian National News Agency (BERNAMA) The Malaysian National News Agency or BERNAMA, a statutory body, was set up by an Act of Parliament in 1967 and began operations in May 1968. BERNAMA’s role as a source of reliable and latest news is well known among local & international media including government agencies, corporations, universities and individuals nationwide. Most Malaysian newspapers and electronic media and other international news agencies are BERNAMA subscribers. BERNAMA is operating in the information industry, which is competitive but has tremendous growth potential. BERNAMA is continuously conducting research to upgrade the quality of its products and services which include real-time financial information, real-time news, an electronic library, dissemination of press releases, event management, photo and video footage. 1.2 About MREM Malaysia-Global “Your direct link to the media” MREM is a professional press release distribution service by BERNAMA, Malaysia's National News Agency, a leading supplier of news content to the local and international media. -

An Overview of Federal STEM Education Programs

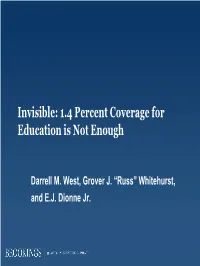

Invisible: 1.4 Percent Coverage for Education is Not Enough Darrell M. West, Grover J. “Russ” Whitehurst, and E.J. Dionne Jr. Methodology • Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism - Coded content daily from a sample of newspapers, network news, cable news, news and talk radio, and online news - Samples are purposeful rather than representative - Selection bias for important stories • Brookings: coded content of all AP education wire stories • Brookings: qualitative study of blogs and local newspapers Newspapers Online Network TV Cable Radio Yahoo news ABC Good CNN daytime NPR Morning Edition NY Times Morning America MSNBC.com ABC World News Situation Room Rush Limbaugh Washington Post Tonight Wall Street Journal NYTimes.com NBC Today Show Anderson Cooper 360 Ed Schultz USA Today Google news NBC Nightly News Lou Dobbs Randi Rhodes washingtonpost.com CBS The Early CNN Prime Time Michael Savage LA Times Show cnn.com CBS Evening MSNBC daytime Sean Hannity Kansas City Star News Pittsburgh Post- aol news PBS Newshour Hardball ABC News Gazette Headlines San Antonio foxnews.com Rachel Maddow CBS News Express-News Headlines San Jose Mercury USAtoday.com The Ed Show News Herald News abcnews.com Countdown Anniston Star BBC News Fox News special Spokesman-Review Reuters.com Fox News daytime Meadville Tribune O'Reilly Factor Fox Report with Shepard Smith Hannity (TV) Special Report w/ Bret Baier Government National News Coverage 2009 Economics Foreign (non-U.S.) U.S. Foreign affairs 12 Health/Medicine Business Crime 10 Campaign/Elections/Politics -

Interview for Interfax News Agency (Olga Golovanova) with Javier

Interview for Interfax news agency (Olga Golovanova) with Javier Solana, EU High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy, on 23 May 2006 1. How would you assess the state of relations between Russia and the European Union? What in your opinion helps broaden cooperation and what factors have been impeding it? We have close ties with Russia, which is a partner of great importance to he EU. Our relationship is a strategic partnership, based on shared values and shared interests, which we want to develop further. 2. The current summit is kind of assessing the results of Russian and EU experts' lengthy effort to forge bilateral agreements relaxing visa procedures and regulating readmission. What do you think is the role of these documents in a broad context for the people of Russia and EU countries? What are prospects for advancement towards a visa-free regime in our citizens' travel? The agreements on visa facilitation and readmission will be signed at the Summit. Russians coming to EU countries and citizens of EU Member States going to Russia will find it cheaper and easier to get visas. This will make a big difference to, for example, Russian holidaymakers and businesspeople coming to the EU. Although we have not agreed yet on a visa free regime, the visa facilitation agreement brings us a step closer to that objective. The agreement on readmission means that the EU and Russia will be able to improve their co-operation in tackling illegal immigration and asylum, a responsibility that we share as neighbours. 1 3. -

Marketing & Communications Style Guide

Marketing & Communications Style Guide January 2018 Fifth Edition The Ryerson University Marketing and Communications Document Style Guide has been developed to facilitate consistency and clarity in the delivery of communication material pertaining Overview to the university. While it was developed specifically for public material produced by University Relations, the guide is made available to all members of the Ryerson community for use as a helpful reference if desired. Style rules for formal material such as letters, invitations, certificates and the like can differ from these guidelines. Similar to most Canadian universities, Ryerson follows the style of Canadian Press (CP). Details on Canadian Press style are outlined in The Canadian Press Stylebook and The Canadian Press Caps and Spelling. The Canadian Oxford Dictionary is also a valuable reference, particularly for spelling. This guide is meant to serve as a supplement to these reference books. It also outlines deviations from Canadian Press style that are particular to Ryerson University. Note: This style guide is organized by general category and then subdivided into a list of rules or subcategories. b Ryerson University Marketing & Communications Style Guide CONTENTS Table of Contents Abbreviations 1 Commonly used words Numbers 7 Formats, commonly used terms and terms at Ryerson 4 Time references, phone numbers, spelling out Teams, academic terms, schools, programs Alumni 1 Punctuation 7 4 Terms for men, women and groups; references Degrees Apostrophes, colons, commas, dashes