Programming Women: Gender at the Birth of the Computing Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Computing

History of Computing CSE P590A (UW) PP190/290-3 (UCB) CSE 290 291 (D00) Women in Computing Katherine Deibel University of Washington [email protected] 1 An Amazing Photo Philadelphia Inquirer, "Your Neighbors" article, 8/13/1957 2 Diversity Crisis in Computer Science Percentage of CS/IS Bachelor Degrees Awarded to Women National Center for Education Statistics, 2001 3 Goals of this talk ! Highlight the many accomplishments made by women in the computing field ! Learn their stories, both good and bad 4 Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace ! Translated and extended Menabrea’s article on Babbage’s Analytical Engine ! Predicted computers could be used for music and graphics ! Wrote the first algorithm— how to compute Bernoulli numbers ! Developed notions of looping and subroutines 5 Garbage In, Garbage Out The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. — Ada Lovelace, Note G 6 On her genius and insight If you are as fastidious about the acts of your friendship as you are about those of your pen, I much fear I shall equally lose your friendship and your Notes. I am very reluctant to return your admirable & philosophic 'Note A.' Pray do not alter it… All this was impossible for you to know by intuition and the more I read your notes the more surprised I am at them and regret not having earlier explored so rich a vein of the noblest metal. -

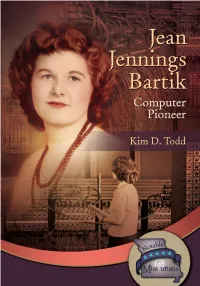

Computer Pioneer / Kim Todd

Copyright © 2015 Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 All rights reserved tsup.truman.edu Cover art: Betty Jean Jennings, ca. 1941; detail of ENIAC, 1946. Cover design: Teresa Wheeler Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Todd, Kim D., author. Jean Jennings Bartik : computer pioneer / Kim Todd. pages cm—(Notable Missourians) Summary: “As a young girl in the 1930s, Jean Bartik dreamed of adventures in the world beyond her family’s farm in northwestern Missouri. After college, she had her chance when she was hired by the U.S. Army to work on a secret project. At a time when many people thought women could not work in technical fields like science and mathematics, Jean became one of the world’s first computer programmers. She helped program the ENIAC, the first successful stored-program computer, and had a long career in the field of computer science. Thanks to computer pioneers like Jean, today we have computers that can do almost anything.”—Provided by publisher. Audience: Ages 10-12. Audience: Grades 4 to 6. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61248-145-6 (library binding : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-1-61248-146-3 (e-book) 1. Bartik, Jean--Juvenile literature. 2. Women computer scientists—United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 3. Computer scientists— United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 4. Women computer programmers— United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 5. Computer programmers—United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. 6. ENIAC (Computer)—History—Juvenile literature. 7. Computer industry—United States—History—Juvenile literature. I. Title. QA76.2.B27T63 2015 004.092--dc23 2015011360 No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any format by any means without written permission from the publisher. -

Working on ENIAC: the Lost Labors of the Information Age

Working on ENIAC: The Lost Labors of the Information Age Thomas Haigh www.tomandmaria.com/tom University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee & Mark Priestley www.MarkPriestley.net This Research Is Sponsored By • Mrs L.D. Rope’s Second Charitable Trust • Mrs L.D. Rope’s Third Charitable Trust Thanks for contributions by my coauthors Mark Priestley & Crispin Rope. And to assistance from others including Ann Graf, Peter Sachs Collopy, and Stephanie Dick. www.EniacInAction.com CONVENTIONAL HISTORY OF COMPUTING www.EniacInAction.com The Battle for “Firsts” www.EniacInAction.com Example: Alan Turing • A lone genius, according to The Imitation Game – “I don’t have time to explain myself as I go along, and I’m afraid these men will only slow me down” • Hand building “Christopher” – In reality hundreds of “bombes” manufactured www.EniacInAction.com Isaacson’s “The Innovators” • Many admirable features – Stress on teamwork – Lively writing – References to scholarly history – Goes back beyond 1970s – Stresses role of liberal arts in tech innovation • But going to disagree with some basic assumptions – Like the subtitle! www.EniacInAction.com Amazon • Isaacson has 7 of the top 10 in “Computer Industry History” – 4 Jobs – 3 Innovators www.EniacInAction.com Groundbreaking for “Pennovation Center” Oct, 2014 “Six women Ph.D. students were tasked with programming the machine, but when the computer was unveiled to the public on Valentine’s Day of 1946, Isaacson said, the women programmers were not invited to the black tie event after the announcement.” www.EniacInAction.com Teams of Superheroes www.EniacInAction.com ENIAC as one of the “Great Machines” www.EniacInAction.com ENIAC Life Story • 1943: Proposed and approved. -

Baixar Baixar

PROTAGONISMO FEMININO NA COMPUTAÇÃO Desmistificando a Ausência de Mulheres Influentes na Área Tecnológica ISBN: 978-65-5825-001-2 PROTAGONISMO FEMININO NA COMPUTAÇÃO: DESMISTIFICANDO A AUSÊNCIA DE MULHERES INFLUENTES NA ÁREA TECNOLÓGICA Alana Morais Aline Morais (Organizadoras) Centro Universitário - UNIESP Cabedelo - PB 2020 CENTRO UNIVERSITÁRIO UNIESP Reitora Érika Marques de Almeida Lima Cavalcanti Pró-Reitora Acadêmica Iany Cavalcanti da Silva Barros Editor-chefe Cícero de Sousa Lacerda Editores assistentes Hercilio de Medeiros Sousa Josemary Marcionila F. R. de C. Rocha Editora-técnica Elaine Cristina de Brito Moreira Corpo Editorial Ana Margareth Sarmento – Estética Anneliese Heyden Cabral de Lira – Arquitetura Daniel Vitor da Silveira da Costa – Publicidade e Propaganda Érika Lira de Oliveira – Odontologia Ivanildo Félix da Silva Júnior – Pedagogia Jancelice dos Santos Santana – Enfermagem José Carlos Ferreira da Luz – Direito Juliana da Nóbrega Carreiro – Farmácia Larissa Nascimento dos Santos – Design de Interiores Luciano de Santana Medeiros – Administração Marcelo Fernandes de Sousa – Computação Márcia de Albuquerque Alves – Ciências Contábeis Maria da Penha de Lima Coutinho – Psicologia Paula Fernanda Barbosa de Araújo – Medicina Veterinária Rita de Cássia Alves Leal Cruz – Engenharia Rogério Márcio Luckwu dos Santos – Educação Física Zianne Farias Barros Barbosa –Nutrição Copyright © 2020 – Editora UNIESP É proibida a reprodução total ou parcial, de qualquer forma ou por qualquer meio. A violação dos direitos autorais (Lei no 9.610/1998) é crime estabelecido no artigo 184 do Código Penal. O conteúdo desta publicação é de inteira responsabilidade do(os) autor(es). Designer Gráfico: Samara Cintra Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca Padre Joaquim Colaço Dourado (UNIESP) M828p Morais, Alana. -

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's

Doing Mathematics on the ENIAC. Von Neumann's and Lehmer's different visions.∗ Liesbeth De Mol Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science University of Ghent, Blandijnberg 2, 9000 Gent, Belgium [email protected] Abstract In this paper we will study the impact of the computer on math- ematics and its practice from a historical point of view. We will look at what kind of mathematical problems were implemented on early electronic computing machines and how these implementations were perceived. By doing so, we want to stress that the computer was in fact, from its very beginning, conceived as a mathematical instru- ment per se, thus situating the contemporary usage of the computer in mathematics in its proper historical background. We will focus on the work by two computer pioneers: Derrick H. Lehmer and John von Neumann. They were both involved with the ENIAC and had strong opinions about how these new machines might influence (theoretical and applied) mathematics. 1 Introduction The impact of the computer on society can hardly be underestimated: it affects almost every aspect of our lives. This influence is not restricted to ev- eryday activities like booking a hotel or corresponding with friends. Science has been changed dramatically by the computer { both in its form and in ∗The author is currently a postdoctoral research fellow of the Fund for Scientific Re- search { Flanders (FWO) and a fellow of the Kunsthochschule f¨urMedien, K¨oln. 1 its content. Also mathematics did not escape this influence of the computer. In fact, the first computer applications were mathematical in nature, i.e., the first electronic general-purpose computing machines were used to solve or study certain mathematical (applied as well as theoretical) problems. -

Download Issue As

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday April 6, 2021 Volume 67 Number 33 www.upenn.edu/almanac Graduate School Rankings 2022 Penn Medicine Researcher: $1 Million Grant to Expand COVID-19 Each year, U.S. News & World Report ranks Treatment Discovery Platform graduate and professional schools in business, David C. Fajgenbaum, an assistant professor treatments for well-designed clinical trials and to medicine, education, law, engineering and nursing. of translational medicine & human genetics and inform patient care. With funding from PICI, sev- Five of Penn’s Schools are in the top 10 list. Those the director of the Center for Cytokine Storm eral new tools are in development or have already in the top 30 are below; for more, see U.S. News’ Treatment & Laboratory at the Perelman School been built, including an open-access dashboard website: www.usnews.com. of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, that integrates data between studies and presents 2021 2022 was awarded $1 million by the Parker Insti- vital data points for prioritizing promising treat- Wharton School 1 2 Finance 1 1 tute for Cancer Immunotherapy (PICI) to ex- ments, such as the number of randomized control Real Estate - 1 pand the scope of the trials that have been completed, the number that Marketing 2 2 COVID-19 Registry are open, the number that achieved their primary Executive MBA 3 2 of Off-label & New endpoint, and others. Accounting 3 3 Agents (CORONA) “All of the really relevant and important data Business Analytics 5 3 project and build out is listed right next to each COVID-19 drug and Management 7 4 his team to accelerate kept up to date,” Dr. -

To Give WITI Members Some Perspective, Jean and Timothy

OLYMPIC PLAZA 11500 Olympic Blvd., Suite 400 Los Angeles, CA 90064 (818) 788-9484 To give WITI Members some perspective, Jean and Timothy Bartik revisited how the six "Women of the ENIAC," WITI Hall of Fame Inductees Kay Antonelli, Jean Bartik, Betty Holberton, Marlyn Meltzer, Frances Spence and Ruth Teitelbaum, fit the criteria for induction into the WITI Hall of Fame in 2005. All the Women of the ENIAC were already inducted to the WITI Hall of Fame in 1997. WITI audaciously asked the Bartiks, as a writing exercise, to fill in the nomination form once again. They graciously agreed to take the WITI challenge with pride. Below are the questions from the 2005 Nomination Form and the responses from Jean and Timothy. WITI Hall of Fame Criteria and Required Questions Hall of Fame recipients include women who have made outstanding contributions based on one or more of the following criteria: 1. Directly made an exceptional contribution to the advancement of science and/or technology. 2. Facilitated and created programs that motivate young women to choose careers in science and technology. 3. Enabled and encouraged other scientific and technical women to advance in their careers 4. Created scientific or technological innovations, which promote environmental harmony, support humanitarian endeavors or improve the human condition. Based on the above recipient criteria, please answer the following questions. Answering these questions is required. Please give thorough and complete answers to questions below. 1. Based on the criteria above, which of these criteria best describes the outstanding contributions of the nominee and why? The Women of the ENIAC, Kay Antonelli, Jean Bartik, Betty Holberton, Marlyn Meltzer, Frances Spence and Ruth Teitelbaum, directly made a contribution to the advancement of science and technology by developing the first programs or software for the first electronic computer, the ENIAC, in the mid 1940s. -

Historia De La Computación

CARLOS ALBERTO GARRIDO LÓPEZ HISTORIA DE LA COMPUTACIÓN Asesora: Dra. Olga María Cossich Mérida Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala Facultad de Humanidades Departamento de Postgrado Maestría en Docencia Universitaria Con Especialidad en Evaluación Educativa Guatemala, octubre de 2008 El presente trabajo de tesis fue presentado por el autor como requisito previo a su graduación de Maestría en Docencia Universitaria con Especialización en Evaluación Educativa. ÍNDICE CONTENIDO NÚMERO DE PAGÍNA INTRODUCCIÓN ...................................................................................................................................................... II ÍNDICE DE ILUSTRACIONES ................................................................................................................................... IV CAPÍTULO I HISTORIA DE LAS MÁQUINAS DE CONTAR ........................................................................................... 1 CAPÍTULO II GENERACIONES DE COMPUTADORAS ................................................................................................. 9 CAPÍTULO III FUNCIONAMIENTO DE LA COMPUTADORA ..................................................................................... 15 CAPÍTULO IV PARTES DE LA COMPUTADORA ....................................................................................................... 22 CAPÍTULO V SOFTWARE ....................................................................................................................................... 45 CAPÍTULO VI LENGUAJES -

The ENIAC: the Grandfather of All Computers

The ENIAC: The Grandfather of all Computers Brian L. Stuart Drexel University The ENIAC 1 What Is ENIAC? • Large-scale computing system • Built during WWII • Dedicated February 15, 1946 • Converted to sequential instruction execution in 1948 • Retired 1955 • Used for: – Atomic bomb development – Ballistics trajectories – Number theory – Supersonic air flow – Weather prediction – and more 2 Common Statistics • 40 racks, each 8’ by 2’ • About 18,000 tubes • 100KHz basic clock • 200µS addition time • About 150KW of power 3 Key People 4 Key People Herman Goldstine Arthur Burks Harry Huskey 5 Key People • Kay Mauchly (Kathleen McNulty Mauchly Antonelli) • Fran Bilas (Frances Bilas Spence) • Jean Bartik (Betty Jean Jennings Bartik) • Betty Holberton (Frances Elizabeth Snyder Holberton) • Ruth Lichterman (Ruth Lichterman Teitelbaum) • Marlyn Wescoff (Marlyn Wescoff Meltzer) • Adele Goldstine (Adele Katz Goldstine) 6 Key People Kay Mauchly Fran Bilas Jean Bartik 7 Key People Betty Holberton Ruth Lichterman Marlyn Wescoff 8 Key People 9 Basic Architecture • Initiating unit • Cycling unit • Two-panel master programmer • 20 Accumulator units • Multiplying unit • Divider/Square rooter unit • 3 Function table units • Constant transmitter/card reader unit • Card punch unit 10 Moore School Layout 11 Unusual Characteristics • No bulk writeable memory • No separation between storage and computation • Divider/square rooter not always exact • Initially programmed with wires and switches • Feels like a dataflow architecture 12 Accumulator • 10 digits + sign (P -

The Women of ENIAC

The Women of ENIAC W. BARKLEY FRITZ A group of young women college graduates involved with the EFJIAC are identified. As a result of their education, intelligence, as well as their being at the right place and at the right time, these young women were able to per- form important computer work. Many learned to use effectively “the machine that changed the world to assist in solving some of the important scientific problems of the time. Ten of them report on their background and experi- ences. It is now appropriate that these women be given recognition for what they did as ‘pioneers” of the Age of Computing. introduction any young women college graduates were involved in ties of some 50 years ago, you will note some minor inconsiskn- NI[ various ways with ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integra- cies, which arc to be expected. In order to preserve the candor and tor And Computer) during the 1942-195.5 period covering enthusiasm of these women for what they did and also to provide ENIAC’s pre-development, development, and 10-year period of today’s reader and those of future generations with their First-hand its operational usage. ENIAC, as is well-known, was the first accounts, I have attempted to resolve only the more serious incon- general purpose electronic digital computer to be designed, built, sistencies. Each of the individuals quoted, however, has been and successfully used. After its initial use for the Manhattan Proj- given an opportunity to see the remarks of their colleagues and to ect in the fall of 194.5 and its public demonstration in February modify their own as desired. -

John W. Mauchly Papers Ms

John W. Mauchly papers Ms. Coll. 925 Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel. Last updated on April 27, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2015 September 9 John W. Mauchly papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Series I. Youth, education, and early career......................................................................................... 10 Series II. Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania................................. -

Jean Jennings Bartik, a Computer Pioneer, Dies at 86 - Nytimes.Com 4/12/11 10:16 AM

Jean Jennings Bartik, a Computer Pioneer, Dies at 86 - NYTimes.com 4/12/11 10:16 AM HOME PAGE TODAY'S PAPER VIDEO MOST POPULAR TIMES TOPICS Subscribe to The Times Log In Register Now Help Search All NYTimes.com Business Day WORLD U.S. N.Y. / REGION BUSINESS TECHNOLOGY SCIENCE HEALTH SPORTS OPINION ARTS STYLE TRAVEL JOBS REAL ESTATE AUTOS Global DealBook Markets Economy Energy Media Personal Tech Small Business Your Money Jean Bartik, Software Pioneer, Dies at 86 Log in to see what your friends Log In With Facebook are sharing on nytimes.com. By STEVE LOHR Privacy Policy | What’s This? Published: April 7, 2011 Jean Jennings Bartik, one of the first computer programmers and a pioneering RECOMMEND What’s Popular Now forerunner in a technology that came to be known as software, died on March TWITTER Poetry for A Stuffed Polar 23 at a nursing home in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. She was 86. Everyday Life Bear Won’t Do SIGN IN TO E- for Berlin’s Fans MAIL Enlarge This Image The cause was congestive heart disease, her of Knut son, Timothy Bartik, said. PRINT Ms. Bartik was the last surviving member of REPRINTS the group of women who programmed the SHARE Eniac, or Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, which is credited as the first all-electronic digital computer. Northwest Missouri State University and the The Eniac, designed to calculate the firing Jean Jennings Bartik Computing Museum Jean Bartik, right, and Kay McNulty trajectories for artillery shells, turned out to be a historic Mauchly Antonelli, widow of John demonstration project.