Graphs As a Managerial Tool: a Case Study of Du Font's Use of Graphs, 1904-1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500–1660

58 • Chartmaking in England and Its Context, 1500 –1660 Sarah Tyacke Introduction was necessary to challenge the Dutch carrying trade. In this transitional period, charts were an additional tool for The introduction of chartmaking was part of the profes- the navigator, who continued to use his own experience, sionalization of English navigation in this period, but the written notes, rutters, and human pilots when he could making of charts did not emerge inevitably. Mariners dis- acquire them, sometimes by force. Where the navigators trusted them, and their reluctance to use charts at all, of could not obtain up-to-date or even basic chart informa- any sort, continued until at least the 1580s. Before the tion from foreign sources, they had to make charts them- 1530s, chartmaking in any sense does not seem to have selves. Consequently, by the 1590s, a number of ship- been practiced by the English, or indeed the Scots, Irish, masters and other practitioners had begun to make and or Welsh.1 At that time, however, coastal views and plans sell hand-drawn charts in London. in connection with the defense of the country began to be In this chapter the focus is on charts as artifacts and made and, at the same time, measured land surveys were not on navigational methods and instruments.4 We are introduced into England by the Italians and others.2 This lack of domestic production does not mean that charts I acknowledge the assistance of Catherine Delano-Smith, Francis Her- and other navigational aids were unknown, but that they bert, Tony Campbell, Andrew Cook, and Peter Barber, who have kindly commented on the text and provided references and corrections. -

3B – a Guide to Pictograms

3b – A Guide to Pictograms A pictogram involves the use of a symbol in place of a word or statistic. Why would we use a pictogram? Pictograms can be very useful when trying to interpret data. The use of pictures allows the reader to easily see the frequency of a geographical phenomenon without having to always read labels and annotations. They are best used when the aesthetic qualities of the data presentation are more important than the ability to read the data accurately. Pictogram bar charts A normal bar chart can be made using a set of pictures to make up the required bar height. These pictures should be related to the data in question and in some cases it may not be necessary to provide a key or explanation as the pictures themselves will demonstrate the nature of the data inherently. A key may be needed if large numbers are being displayed – this may also mean that ‘half’ sized symbols may need to be used too. This project was funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Foundation. Proportional shapes and symbols Scaling the size of the picture to represent the amount or frequency of something within a data set can be an effective way of visually representing data. The symbol should be representative of the data in question, or if the data does not lend itself to a particular symbol, a simple shape like a circle or square can be equally effective. Proportional symbols can work well with GIS, where the symbols can be placed on different sites on the map to show a geospatial connection to the data. -

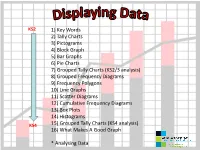

1) Key Words 2) Tally Charts 3) Pictograms 4) Block Graph 5) Bar

KS2 1) Key Words 2) Tally Charts 3) Pictograms 4) Block Graph 5) Bar Graphs 6) Pie Charts 7) Grouped Tally Charts (KS2/3 analysis) 8) Grouped Frequency Diagrams 9) Frequency Polygons 10) Line Graphs 11) Scatter Diagrams 12) Cumulative Frequency Diagrams 13) Box Plots 14) Histograms KS4 15) Grouped Tally Charts (KS4 analysis) 16) What Makes A Good Graph * Analysing Data Key words Axes Linear Continuous Median Correlation Origin Plot Data Discrete Scale Frequency x -axis Grouped y -axis Interquartile Title Labels Tally Types of data Discrete data can only take specific values, e.g. siblings, key stage 3 levels, numbers of objects Continuous data can take any value, e.g. height, weight, age, time, etc. Tally Chart A tally chart is used to organise data from a list into a table. The data shows the number of children in each of 30 families. 2, 1, 5, 0, 2, 1, 3, 0, 2, 3, 2, 4, 3, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 4, 0, 1, 3, 1, 2, 2, 6, 3, 2, 2, 3 Number of children in a Tally Frequency family 0 1 2 3 4 or more Year 3/4/5/6:- represent data using: lists, tally charts, tables and diagrams Tally Chart This data can now be represented in a Pictogram or a Bar Graph The data shows the number of children in each family. 30 families were studied. Add up the tally Number of children in a Tally Frequency family 0 III 3 1 IIII I 6 2 IIII IIII 10 3 IIII II 7 4 or more IIII 4 Total 30 Check the total is 30 IIII = 5 Year 3/4/5/6:- represent data using: lists, tally charts, tables and diagrams Pictogram This data could be represented by a Pictogram: Number of Tally Frequency -

2021 Garmin & Navionics Cartography Catalog

2021 CARTOGRAPHY CATALOG CONTENTS BlueChart® Coastal Charts �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 04 LakeVü Inland Maps �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 06 Canada LakeVü G3 �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 08 ActiveCaptain® App �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 09 New Chart Guarantee� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 How to Read Your Product ID Code �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 10 Inland Maps ��������������������������������������������������� 12 Coastal Charts ������������������������������������������������� 16 United States� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 18 Canada ���������������������������������������������������� 24 Caribbean �������������������������������������������������� 26 South America� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 27 Europe����������������������������������������������������� 28 Africa ����������������������������������������������������� 39 Asia ������������������������������������������������������ 40 Australia/New Zealand �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 42 Pacific Islands �� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

1. What Is a Pictogram? 2

Canonbury Home Learning Year 2/3 Maths Steppingstone activity Lesson 5 – 26.06.2020 LO: To interpret and construct simple pictograms Success Criteria: 1. Read the information about pictograms 2. Use the information in the Total column to complete the pictogram 3. Find some containers around your house and experiment with their capacity – talk through the questions with someone you live with 1. What is a pictogram? 2. Complete the pictogram: A pictogram is a chart or graph which uses pictures to represent data. They are set out the same way as a bar chart but use pictures instead of bars. Each picture could represent one item or more than one. Today we will be drawing pictograms where each picture represents one item. 2. Use the tally chart to help you complete the pictogram: Canonbury Home Learning Year 2/3 Maths Lesson 5 – 26.06.2020 LO: To interpret and construct simple pictograms Task: You are going to be drawing pictograms 1-1 Success Criteria: 1. Read the information about pictograms 2. Task 1: Use the information in the table to complete the pictogram 3. Task 2: Use the information in the tally chart and pictogram to complete the missing sections of each Model: 2. 3. 1. What is a pictogram? A pictogram is a chart or graph which uses pictures to represent data. They are set out the same way as a bar chart but use pictures instead of bars. Each picture could represent one item or more than one. Today we will be drawing pictograms where each picture represents one item. -

Visualization

Visualization Computer Graphics II University of Missouri at Columbia Visualization •• “a“a picturepicture sayssays moremore thanthan aa thousandthousand words”words” Computer Graphics II University of Missouri at Columbia Visualization •• “a“a picturepicture sayssays moremore thanthan aa thousandthousand numbers”numbers” Computer Graphics II University of Missouri at Columbia Visualization •• VVisualizationisualization cancan facilitatefacilitate peoplepeople toto betterbetter understandunderstand thethe informationinformation embeddedembedded inin thethe givengiven dataset.dataset. •• TThehe mergemerge ofof datadata withwith thethe displaydisplay geometricgeometric objectsobjects throughthrough computercomputer graphics.graphics. Computer Graphics II University of Missouri at Columbia Data •2•2DD ddaattaasseett –– BBarar chart,chart, piepie chart,chart, graph,graph, stocks.stocks. –– IInformationnformation visualizationvisualization •3•3DD ddaattaasseett –– SScalarcalar datadata –V–Veeccttoorr ddaattaa –T–Teennssoorr ddaattaa Computer Graphics II University of Missouri at Columbia Data •2•2DD ddaattaasseett –– BBarar chart,chart, piepie chart,chart, graph,graph, stocks.stocks. –– IInformationnformation visualizationvisualization •3•3DD ddaattaasseett –– SScalarcalar datadata –V–Veeccttoorr ddaattaa –T–Teennssoorr ddaattaa Computer Graphics II University of Missouri at Columbia Data •2•2DD ddaattaasseett –– BBarar chart,chart, piepie chart,chart, graph,graph, stocks.stocks. –– IInformationnformation visualizationvisualization •3•3DD -

Infographic Designer Quick Start

Infographic Designer Quick Start Infographic Designer is a Power BI custom visual to provide infographic presentation of data. For example, using Infographic Designer, you can create pictographic style column charts or bar charts as shown in Fig. 1. Unlike standard column charts or bar charts, they use a single icon or stacked multiple icons to constitute a column or bar. Icons convey the data concepts in concrete objects, and the size and number of icons can represent data quantities intuitively. Research reveals that such infographics can improve the effectiveness of visualizations by making data quickly understood and easily remembered. As a result, they are getting popular and have been widely adopted in the real world. Now with Infographic Designer, you are able to create infographic visuals in Power BI easily. (A) (B) (C) (D) Fig. 1. Example infographics created by Infographic Designer Overview Infographic Designer visual is structured as a small multiple, where each individual view is a chart of a particular chart type (Fig. 2). Currently it supports column chart, bar chart, and card chart. More chart types (line chart, scatter chart, etc.) will be added in the future. In Fig. 2, A is a small multiple of card chart, and B is a small multiple of column chart. As a special case, when a small multiple comes to 1X1, it is identical to a single chart (see the charts in Fig. 1). (A) (B) Fig. 2. Infographic Designer small multiples For the individual views of the small multiple, Infographic Designer allows you to customize the chart marks to achieve beautiful, readable, and friendly visualizations. -

Data-Driven Guides: Supporting Expressive Design for Information Graphics

Data-Driven Guides: Supporting Expressive Design for Information Graphics Nam Wook Kim, Eston Schweickart, Zhicheng Liu, Mira Dontcheva, Wilmot Li, Jovan Popovic, and Hanspeter Pfister 300 240 200 300 240 200 120 80 60 120 80 60 '82est '82est '80 '80 300 '78 '78 '76 '76 '74 '74 1972 1972 240 200 120 80 300 300 60 '82est 240 '80 240 '78 120 '76 200 200 '74 120 80 1972 60 '82est 80 60 '80 '82est '78 '80 '76 '78 '74 '76 1972 '74 1972 Fig. 1: Nigel Holmes’ Monstrous Costs chart, recreated by importing a monster graphic (left) and retargeting the teeth of the monster with DDG (middle). Taking advantage of the data-binding capability of DDG, small multiples are easily created by copying the chart and changing the data for each cloned chart (right). Abstract—In recent years, there is a growing need for communicating complex data in an accessible graphical form. Existing visualization creation tools support automatic visual encoding, but lack flexibility for creating custom design; on the other hand, freeform illustration tools require manual visual encoding, making the design process time-consuming and error-prone. In this paper, we present Data-Driven Guides (DDG), a technique for designing expressive information graphics in a graphic design environment. Instead of being confined by predefined templates or marks, designers can generate guides from data and use the guides to draw, place and measure custom shapes. We provide guides to encode data using three fundamental visual encoding channels: length, area, and position. Users can combine more than one guide to construct complex visual structures and map these structures to data. -

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Coronavirus Graphs Jürgen Symanzik Utah State University Logan, UT, USA [email protected]

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Coronavirus Graphs Jürgen Symanzik Utah State University Logan, UT, USA [email protected] http://www.math.usu.edu/~symanzik Southwest Michigan Chapter of the American Statistical Association (ASA), Virtual January 7, 2021 Contents Motivation “How to Display Data Badly” The Bad and the Ugly Ones The Good Ones Summary & Discussion Bad Graphs Collections on the Web Sources for Constructing Better Graphs Motivation From: Zelazny, G. (2001), Say it with Charts: The Executive's Guide to Visual Communication (Fourth Edition), McGraw-Hill, New York, NY. Motivation As an expert in statistical graphics, it hurts to see bad graphs in the news, on the web, and produced by students. Even worse are bad graphs in science (including those from articles in peer-reviewed journals). As the former chair of a task force of the Statistical Graphics Section of the American Statistical Association (ASA), we reevaluated the winning posters of the annual ASA poster competition for children from kindergarten to grade 12 – and noticed many bad graphs, even among the winners. I am permanently on the lookout for bad graphs. “How to Display Data Badly” “How to Display Data Badly” From: Wainer, H. (1997), Visual Revelations: Graphical Tales of Fate and Deception from Napoleon Bonaparte to Ross Perot, Copernicus/Springer, New York, NY: “The aim of good data graphics is to display data accurately and clearly. […] Thus, if we wish to display data badly, we have three avenues to follow. – A. Don't show much data. – B. Show the data inaccurately. – C. Obfuscate the data.” [i.e., show the data unclearly] A. -

Which Chart Or Graph Is Right for You?

Which chart or graph is right for you? Tracy Rodgers, Product Marketing Manager Robert Bloom, Tableau Engineer You’ve got data and you’ve got questions. You know there’s a chart or graph out there that will find the answer you’re looking for, but it’s not always easy knowing which one is best without some trial and error. This paper pairs appropriate charts with the type of data you’re analyzing and questions you want to answer. But it won’t stop there. Stranding your data in isolated, static graphs limits the number and depth of questions you can answer. Let your analysis become your organization’s centerpiece by using it to fuel exploration. Combine related charts. Add a map. Provide filters to dig deeper. The impact? Immediate business insight and answers to questions that actually drive decisions. So, which chart is right for you? Transforming data into an effective visualization (any kind of chart or graph) or dashboard is the first step towards making your data make an impact. Here are some best practices for conducting meaningful visual analysis: 2 Bar chart Bar charts are one of the most common data visualizations. With them, you can quickly highlight differences between categories, clearly show trends and outliers, and reveal historical highs and lows at a glance. Bar charts are especially effective when you have data that can be split into multiple categories. Use bar charts to: • Compare data across categories. Bar charts are best suited for data that can be split into several groups. For example, volume of shirts in different sizes, website traffic by referrer, and percent of spending by department. -

How to Spot a Misleading Graph - Lea Gaslowitz.Mp4

How to spot a misleading graph - Lea Gaslowitz.mp4 [00:00:07] A toothpaste brand claims their product will destroy more plaque than any product ever made. A politician tells you their plan will create the most jobs. We're so used to hearing these kinds of exaggerations, and advertising, and politics that we might not even bat an eye. [00:00:22] But what about when the claim is accompanied by a graph? After all, a graph isn't an opinion. It represents cold, hard numbers. And who can argue with those? [00:00:32] Yet, as it turns out, there are plenty of ways graphs can mislead and outright manipulate. Here are some things to look out for. [00:00:40] In this 1992 ad, Chevy claimed to make the most reliable trucks in America, using this graph. Not only does it show that 98 percent of all Chevy trucks sold in the last 10 years are still on the road, but it looks like they're twice as dependable as Toyota trucks. That is, until you take a closer look at the numbers on the left and see that the figure for Toyota is about 96.5 percent. The scale only goes between 95 and 100 percent. If it went from zero to 100, it would look like this. [00:01:12] This is one of the most common ways that graphs misrepresent data by distorting the scale. [00:01:18] Zooming in on a small portion of the Y-axis exaggerates a barely detectable difference between the things being compared. -

Introduction to Data Visualization Techniques Using Microsoft Excel 2013 & Web-Based Tools

Tufts Data Lab Introduction to Data Visualization Techniques Using Microsoft Excel 2013 & Web-based Tools Revised by Carolyn Talmadge and Jonathan Gale on January 28, 2016 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 CHOOSING THE MOST APPROPRIATE TYPE OF CHART OR GRAPH FOR DATA VISUALIZATION ........................................................... 1 I. SUMMARY TABLES ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 II. BAR CHARTS ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 BAR GRAPHS FOR CATEGORICAL DATA ........................................................................................................................................ 3 BAR GRAPHS FOR LONGITUDINAL DATA ...................................................................................................................................... 4 STAKED BAR CHARTS VS CLUSTERED BAR CHARTS ....................................................................................................................... 4 III. PIE CHARTS .....................................................................................................................................................................................