Health and Safety at Chatham Dockyard, 1945 to 1984. Evaluating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Semaphore Circular No 661 the Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016

The Semaphore Circular No 661 The Beating Heart of the RNA July 2016 The No 3 Area Ladies getting the Friday night raffle ready at Conference! This edition is the on-line version of the Semaphore Circular, unless you have registered with Central Office, it will only be available on the RNA website in the ‘Members Area’ under ‘downloads’ at www.royal-naval-association.co.uk and will be emailed to the branch contact, usually the Hon Sec. 1 Daily Orders 1. Conference 2016 report 2. Remembrance Parade 13 November 2016 3. Slops/Merchandise & Membership 4. Guess Where? 5. Donations 6. Pussers Black Tot Day 7. Birds and Bees Joke 8. SAIL 9. RN VC Series – Seaman Jack Cornwell 10. RNRMC Charity Banquet 11. Mini Cruise 12. Finance Corner 13. HMS Hampshire 14. Joke Time 15. HMS St Albans Deployment 16. Paintings for Pleasure not Profit 17. Book – Wren Jane Beacon 18. Aussie Humour 19. Book Reviews 20. For Sale – Officers Sword Longcast “D’ye hear there” (Branch news) Crossed the Bar – Celebrating a life well lived RNA Benefits Page Shortcast Swinging the Lamp Forms Glossary of terms NCM National Council Member NC National Council AMC Association Management Committee FAC Finance Administration Committee NCh National Chairman NVCh National Vice Chairman NP National President DNP Deputy National President GS General Secretary DGS Deputy General Secretary AGS Assistant General Secretary CONA Conference of Naval Associations IMC International Maritime Confederation NSM Naval Service Memorial Throughout indicates a new or substantially changed entry 2 Contacts Financial Controller 023 9272 3823 [email protected] FAX 023 9272 3371 Deputy General Secretary 023 9272 0782 [email protected] Assistant General Secretary (Membership & Slops) 023 9272 3747 [email protected] S&O Administrator 023 9272 0782 [email protected] General Secretary 023 9272 2983 [email protected] Admin 023 92 72 3747 [email protected] Find Semaphore Circular On-line ; http://www.royal-naval-association.co.uk/members/downloads or.. -

January Cover.Indd

Accessories 1:35 Scale SALE V3000S Masks For ICM kit. EUXT198 $16.95 $11.99 SALE L3H163 Masks For ICM kit. EUXT200 $16.95 $11.99 SALE Kfz.2 Radio Car Masks For ICM kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 5 - Tool Boxes Early German E-50 Flakpanzer Rheinmetall Geraet sWS with 20mm Flakvierling Detail Set EUXT201 $9.95 $7.99 AB35194 $17.99 $16.19 58 5.5cm Gun Barrels For Trumpter EU36195 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L100 $21.99 $19.79 SALE Merkava Mk.3D Masks For Meng kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 4 - Tool Boxes Late Defender 110 Hardtop Detail Set HobbyBoss EUXT202 $14.95 $10.99 AB35195 $17.99 $16.19 Soviet 76.2mm M1936 (F22) Divisional Gun EU36200 $32.95 $29.66 SALE L 4500 Büssing NAG Window Mask KV-1 Vol. 6 - Lubricant Tanks Trumpeter KV-1 Barrel For Bronco kit. GMC Bofors 40mm Detail Set For HobbyBoss For ICM kit. AB35196 $14.99 $14.99 AB35L104 $9.99 EU36208 $29.95 $26.96 EUXT206 $10.95 $7.99 German Heavy Tank PzKpfw(r) KV-2 Vol-1 German Stu.Pz.IV Brumbar 15cm STuH 43 Gun Boxer MRAV Detail Set For HobbyBoss kit. Jagdpanzer 38(t) Hetzer Wheel mask For Basic Set For Trumpeter kit - TR00367. Barrel For Dragon kit. EU36215 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L110 $9.99 Academy kit. AB35212 $25.99 $23.39 Churchill Mk.VI Detail Set For AFV Club kit. EUXT208 $12.95 SALE German Super Heavy Tank E-100 Vol.1 Soviet 152.4mm ML-20S for SU-152 SP Gun EU36233 $26.95 $24.26 Simca 5 Staff Car Mask For Tamiya kit. -

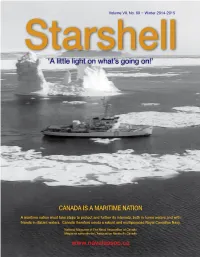

'A Little Light on What's Going On!'

Volume VII, No. 69 ~ Winter 2014-2015 Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ CANADA IS A MARITIME NATION A maritime nation must take steps to protect and further its interests, both in home waters and with friends in distant waters. Canada therefore needs a robust and multipurpose Royal Canadian Navy. National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca On our cover… To date, the Royal Canadian Navy’s only purpose-built, ice-capable Arctic Patrol Vessel, HMCS Labrador, commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy July 8th, 1954, ‘poses’ in her frozen natural element, date unknown. She was a state-of-the- Starshell art diesel electric icebreaker similar in design to the US Coast Guard’s Wind-class ISSN-1191-1166 icebreakers, however, was modified to include a suite of scientific instruments so it could serve as an exploration vessel rather than a warship like the American Coast National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Guard vessels. She was the first ship to circumnavigate North America when, in Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada 1954, she transited the Northwest Passage and returned to Halifax through the Panama Canal. When DND decided to reduce spending by cancelling the Arctic patrols, Labrador was transferred to the Department of Transport becoming the www.navalassoc.ca CGSS Labrador until being paid off and sold for scrap in 1987. Royal Canadian Navy photo/University of Calgary PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele In this edition… PRESIDENT • Jim Carruthers, [email protected] NAC Conference – Canada’s Third Ocean 3 PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] The Editor’s Desk 4 TREASURER • King Wan, [email protected] The Bridge 4 The Front Desk 6 NAVAL AFFAIRS • Daniel Sing, [email protected] NAC Regalia Sales 6 HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

The Heroic Destroyer and "Lucky" Ship O.R.P. "Blyskawica"

Transactions on the Built Environment vol 65, © 2003 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 The heroic destroyer and "lucky" ship O.R.P. "Blyskawica" A. Komorowski & A. Wojcik Naval University of Gdynia, Poland Abstract The destroyer O.R.P. "Blyskawica" is a precious national relic, the only remaining ship that was built before World War I1 (WW2). On the 5oth Anniversary of its service under the Polish flag, it was honoured with the highest military decoration - the Gold Cross of the Virtuti Militari Medal. It has been the only such case in the whole history of the Polish Navy. Its our national hero, war-veteran and very "lucky" warship. "Blyskawica" took part in almost every important operation in Europe throughout WW2. It sailed and covered the Baltic Sea, North Sea, all the area around Great Britain, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. During the war "Blyskawica" covered a distance of 148 thousand miles, guarded 83 convoys, carried out 108 operational patrols, participated in sinking two warships, damaged three submarines and certainly shot down four war-planes and quite probably three more. It was seriously damaged three times as a result of operational action. The crew casualties aggregated to a total of only 5 killed and 48 wounded petty officers and seamen, so it was a very "lucky" ship during WW2. In July 1947 the ship came back to Gdynia in Poland and started training activities. Having undergone rearmament and had a general overhaul, it became an anti-aircraft defence ship. In 1976 it replaced O.R.P. "Burza" as a Museum-Ship. -

Part 4: Conclusions and Recommendations & Appendices

Twentieth Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth: Characterisation Report PART FOUR CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS The final focus of this report is to develop the local, national and international contexts of the two dockyards to highlight specific areas of future research. Future discussion of Devonport and Portsmouth as distinct designed landscapes would coherently organise the many strands identified in this report. The Museum of London Archaeology Portsmouth Harbour Hinterland Project carried out for Heritage England (2015) is a promising step in this direction. It is emphasised that this study is just a start. By delivering the aim and objectives, it has indicated areas of further fruitful research. Project aim: to characterise the development of the active naval dockyards at Devonport and Portsmouth, and the facilities within the dockyard boundaries at their maximum extent during the twentieth century, through library, archival and field surveys, presented and analysed in a published report, with a database of documentary and building reports. This has been delivered through Parts 1-4 and Appendices 2-4. Project objectives 1 To provide an overview of the twentieth century development of English naval dockyards, related to historical precedent, national foreign policy and naval strategy. 2 To address the main chronological development phases to accommodate new types of vessels and technologies of the naval dockyards at Devonport and Portsmouth. 3 To identify the major twentieth century naval technological revolutions which affected British naval dockyards. 4 To relate the main chronological phases to topographic development of the yards and changing technological and strategic needs, and identify other significant factors. 5 To distinguish which buildings are typical of the twentieth century naval dockyards and/or of unique interest. -

Okanagan Nation E-News

S Y I L X OKANAGAN NATION E-NEWS April 2010 Okanagan Nation Jr. Girls Bring Home Provincial Championship Table of Contents HMCS Okanagan 2 Syilx Youth Unity Run 3 Browns Creek 4 Update Child & Family 6 NRLUT Update FN Leaders 7 Denounce Fed Funding Cuts Health Hub 8 Columbia River 9 93,000 Sockeye 10 Released Sturgeon 11 Gathering AA Roundup 12 Photo: Team Mng Lisa Reid, Ashley McGinnis, Dina Brown, Jasmine Reid, Janessa Lambert, Coach Peter Waardenburg, Erica Swan, Jade Waardenburg, Nicola Terbasket, Coach Amanda Montgomery, Kirsten Lindley, Front: Jade Sargent Family 13 Missing Courtney Louie Intervention The Syilx, Okanagan Nation, Jr Girls basketball ball it was stolen by Reid, passed to Sargent and Society Conf ONA Bursary 14 team brought home the Championship and she did a lay in to win the game. Most Sportsmanlike Team after playing 8 R Native Voice 15 “Okanagan girls were full value for the win, University Camp 16 games in Prince Rupert during Spring Break. hard working and all the class in the world.” Fish Lake 17 The final four games were all nail biters, said said Kitimat coach Keith Nyce. What’s Reid; the gym was vibrating with the fans from Happening 18 Other awards included MVP, Jade Toll Free all the villages cheering on their nations. Waardenburg, Best Defense and All Star In the final game against Kitimat there was only 1-866-662-9609 Jasmine Reid, and All Star Ashley McGinnis 9 seconds left, Okanagan down by 2, when Waardenburg drew the foal that would take The Okanagan Nation will host the 2011 Jr All her to the free throw line. -

SALE on the General Rule Is That New Shipboard State Dinner, "Will Surcharge and the Decision to Level Briefly in Tokyo

PAGE FORT? MONDAY, DECEMBER 20, 197J lEorntng 1|?raUi Avarag. Dally Nat Prass Run For The Week Ended The Weather November to, 1971 M. Graves of Storrs, marshal; AboutTown Christmas Party Donald E. Murray of Tolland, Clear and colder tesdght; low Uriel Lodge iianrJjpatpr luem nn in 20s. Tomorrow sunny, oddi; Th« nominatlnf committa* ot organist; Fred H. Bechter of MILK South UnlUd MethodUt Church Produces Gifts West WtUtngton, t y l ^ . Braln 15,590 high -about 40. Thuroday'e oqt- wlU moot tonight at 7 at the look . , , again sunny and ootd. For Many Needy Seats Slate ard, historian and^ Ubrarian; FOR HOMI DUIVIRY Manche»ter— A City of Village Charm church. Officers for Uriel Lodge of Past Master Robert C. Sim 3 TIMRS WIIKLY IN RITURNAMJ Masons for 1972 wars Installed mons of Coventry, custodian of Tte Clvftan Club of Kanchea- Kaiser Hall of Concordia GLASS lo m is VOL. LXXXXI, NO. Lutheran Church on Pitkin Bt. at semi-public installation cere the work; Charles B. Transue of (TWENTY-BIGHT PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, DECEMBER 21, 1971 (Olaasiflod Advertlalng on Pegu SB) tar will meat tomorrow at 13:15 monies at the Masonic ’Temple Manchester, In charge of pub (We beUeve milk taatee better In gbuw) PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS p.m. at WUlla’a Steak Houaa. was the scene of an unusual licity. Christmas party Saturday eve in Merrow on Saturday. ning, hosted by Mr. and Mrs. Ths cerepionlef were opened After the Installation, there The Klvmnla Club of ^an> with introductory remarks by was an Interval for presentation cheater will meet tomorrow Jay R. -

Naval Dockyards Society

20TH CENTURY NAVAL DOCKYARDS: DEVONPORT AND PORTSMOUTH CHARACTERISATION REPORT Naval Dockyards Society Devonport Dockyard Portsmouth Dockyard Title page picture acknowledgements Top left: Devonport HM Dockyard 1951 (TNA, WORK 69/19), courtesy The National Archives. Top right: J270/09/64. Photograph of Outmuster at Portsmouth Unicorn Gate (23 Oct 1964). Reproduced by permission of Historic England. Bottom left: Devonport NAAFI (TNA, CM 20/80 September 1979), courtesy The National Archives. Bottom right: Portsmouth Round Tower (1843–48, 1868, 3/262) from the north, with the adjoining rich red brick Offices (1979, 3/261). A. Coats 2013. Reproduced with the permission of the MoD. Commissioned by The Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England of 1 Waterhouse Square, 138-142 Holborn, London, EC1N 2ST, ‘English Heritage’, known after 1 April 2015 as Historic England. Part of the NATIONAL HERITAGE PROTECTION COMMISSIONS PROGRAMME PROJECT NAME: 20th Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth (4A3.203) Project Number 6265 dated 7 December 2012 Fund Name: ARCH Contractor: 9865 Naval Dockyards Society, 44 Lindley Avenue, Southsea, PO4 9NU Jonathan Coad Project adviser Dr Ann Coats Editor, project manager and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Davies Editor and reviewer, project executive and Portsmouth researcher Dr David Evans Devonport researcher David Jenkins Project finance officer Professor Ray Riley Portsmouth researcher Sponsored by the National Museum of the Royal Navy Published by The Naval Dockyards Society 44 Lindley Avenue, Portsmouth, Hampshire, PO4 9NU, England navaldockyards.org First published 2015 Copyright © The Naval Dockyards Society 2015 The Contractor grants to English Heritage a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, perpetual, irrevocable and royalty-free licence to use, copy, reproduce, adapt, modify, enhance, create derivative works and/or commercially exploit the Materials for any purpose required by Historic England. -

100 Years of Submarines in the RCN!

Starshell ‘A little light on what’s going on!’ Volume VII, No. 65 ~ Winter 2013-14 Public Archives of Canada 100 years of submarines in the RCN! National Magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada www.navalassoc.ca Please help us put printing and postage costs to more efficient use by opting not to receive a printed copy of Starshell, choosing instead to read the FULL COLOUR PDF e-version posted on our web site at http:www.nava- Winter 2013-14 lassoc.ca/starshell When each issue is posted, a notice will | Starshell be sent to all Branch Presidents asking them to notify their ISSN 1191-1166 members accordingly. You will also find back issues posted there. To opt out of the printed copy in favour of reading National magazine of The Naval Association of Canada Starshell the e-Starshell version on our website, please contact the Magazine nationale de L’Association Navale du Canada Executive Director at [email protected] today. Thanks! www.navalassoc.ca PATRON • HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh OUR COVER RCN SUBMARINE CENTENNIAL HONORARY PRESIDENT • H. R. (Harry) Steele The two RCN H-Class submarines CH14 and CH15 dressed overall, ca. 1920-22. Built in the US, they were offered to the • RCN by the Admiralty as they were surplus to British needs. PRESIDENT Jim Carruthers, [email protected] See: “100 Years of Submarines in the RCN” beginning on page 4. PAST PRESIDENT • Ken Summers, [email protected] TREASURER • Derek Greer, [email protected] IN THIS EDITION BOARD MEMBERS • Branch Presidents NAVAL AFFAIRS • Richard Archer, [email protected] 4 100 Years of Submarines in the RCN HISTORY & HERITAGE • Dr. -

60 Years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 - 2018 Part 4: Europe & Canada Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 4: Europe & Canada. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States - Submarines Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications. -

Playing Hickory Golf While You Piece Together a Vintage Set

CHAPTER 10 cmyk 4/11/08 5:13 PM Page 165 Chapter Title CHAPTER 10 Questions And Answers About Hickory Golf Q: How much does it cost to get started in hickory golf? A: You can purchase inexpensive hickory clubs for as little as $25 each. Obviously, these are not likely to be of a premium quality and will probably require work to make them playable. At Classic Golf, we offer fully restored Tom Stewart irons for about $150 each with a one-year warranty on the shafts against breakage. Our restored woods are about $250 each for the premium examples. So, a ten-club set with two woods would run $1,700. A 14-club set would be $2,300. This compares favorably with the purchase of a premium modern 14-club set where your irons are $800, your driver is $400, fairway wood $200, two wedges at $125 each, hybrid at $150, and a putter at $200 for a total of $2,000. Q: Can a beginner or high handicap golfer play hickory golf? A: Yes. That is how it was done 100 years ago! It can be an advantage starting golf with clubs that require a more precise swing. Q: Are there reproduction clubs available and are they allowed in hickory tournaments? A: Reproduction clubs are available from Tad Moore, Barry Kerr, and Louisville Golf. Every tournament has its own set of rules. The National Hickory Championship allows reproductions because pre-1900 clubs are so difficult to find and are very expensive. At the present time there are ample supplies of vintage clubs available for play, but this could change with the increasing popularity of hickory golf. -

Lead and Line April

April 2015 volume 3 0 , i s s u e N o . 4 LEAD AND LINE newsletter of the naval Association of canada-vancouver island Buzzed by Russians...again At sea with Victoria Monsters be here Another cocaine bust Page 2 Page 3 Page 9 Page 14 HMCS Victoria Update... Page 3 Speaker: Captain Bill Noon NAC-VI Topic: Update on the Franklin Expedition 27 Apr Cost will be $25 per person. Luncheon Guests - spouses, friends, family are most welcome Please contact Bud Rocheleau [email protected] or Lunch at the Fireside Grill at 1130 for 1215 250-386-3209 prior to noon on Thursday 19 Mar. 4509 West Saanich Road, Royal Oak, Saanich. NPlease advise of any allergies or food sensitivities Ac NACVI • PO box 5221, Victoria BC • Canada V8R 6N4 • www.noavi.ca • Page 1 April 2015 volume 30 , i s s u e N o . 4 NAC-VI LEAD AND LINE Don’t be so wet! There has been a great kerfuffle on Parliament Hill, and in the press, about the possibility that HMCS Fredericton might have been confronted by a Russian warship and buzzed by Russian fighter jets. Not so says NATO, stating that any Russian vessels were on the horizon and the closest any plane got was 69 kilometers. (Our MND says it was within 500 ft!) An SU-24 Fencer circled HMCS Toronto, during NATO op- And so what if they did? It would hardly be surprising, if erations in the Black Sea last September. in a period of some tension (remember the Ukraine) that a Russian might be interested in scoping out the competition And you can’t tell me that the Americans (who were with us or that we might be interested in doing the same in return.