Hitler's Daughter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackie French Papers

A Guide to the JACKIE FRENCH PAPERS © Courtesy of Bryan Sullivan The Lu Rees Archives of Australian Children’s Literature The Library University of Canberra October 2013 JACKIE FRENCH PAPERS SCOPE AND CONTENT Jackie French donated her first collection of papers and manuscripts to the Lu Rees Archives under the Cultural Gifts Program in 2009, and this, her second Cultural Gifts donation, in 2012. The size of the current collection is seven standard archival boxes plus 14 oversized folders that together comprise 24 representative works from her more than 140 published works. The collection spans the years from 2008 to 2013 and features picture books, information books, historical fiction, science fiction, humorous recreations of historical events and characters, and an unpublished novel for adults. The papers comprise correspondence; readers’ reports; manuscripts in various drafts with comments from editors, book designers, and illustrators; style guides; suggestions for revision; draft text and accompanying preliminary illustrations for picture books which reveal their evolutionary process; galleys and proofs with editing and layout designs. The process of structural and copyediting of longer works is also evident. The work of the book designer is particularly well documented not only in picture books, but also in longer illustrated works. The collection provides an understanding of the collaborative art of the picture book, demonstrating how illustrations and text evolve and elaborate on each through the communication between author, illustrator, editor and book designer. Adaptation of her work, Shaggy Gully Times, into a musical theatre production includes sheet music, play script and DVDs of the performance. The papers were arranged and described by Dr Belle Alderman AM. -

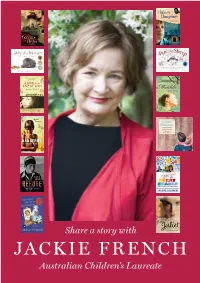

Jackie French Poster

is a full-time writer who lives in rural NSW. She writes columns in the print media, and sometimes presents on radio and on Burke’s Back- yard. Her books for children include Rain Stones, shortlisted for the CBC Children’s Book of the Year Award for Younger Readers, 1991; Walking the Boundaries, a Notable Book in the CBC Awards, 1994; and Somewhere Around the Corner, an Honour Book in the CBC Awards, 1995. In 2000, Hitler’s Daughter won the CBC Younger Readers Award and the WOW! Award in the UK in 2001. How to Guzzle Your Garden was also shortlisted for the 2000 CBC Eve Pownall Award for Information. Most recently, Jackie won the 2002 ACT Book of the Year Award for In the Blood; her successful picture book Diary of a Wombat was named an Honour book in the 2003 CBC Awards and also won the 2003 Nielsen Book Data/ABA Book of the Year Award. Baby Wombats Week New Release Fair Dinkum Histories Diary of a Wombat Shipwrecks, Sailors and 60, 000 years before 1788 Gold Graves and Glory 1850-1880 Emily and the Big Bad Bunyip Grim Crims and Convicts 1888-1820 Nation of Swaggies and Diggers 1880-1920 Josephine Wants To Dance Rotters and Squatters 1820-1850 Weevils, War and Wallabies 1920-1945 Pete the Sheep Shaggy Gully Times, The Too Many Pears Big Burps, Bare Bums and Other Bad Mannered Blunders Rocket Your Child Into Reading Book of Challenges Secret World Of Wombats Beyond the Boundaries The fascinating History of Your Lunch Stamp, Stomp, Whomp The Book of Unicorns How high Can a Kangaroo Hop? To The Moon and Back Dark Wind Blowing Daughter of -

Share a Story With

Share a story with JACKIE FRENCH Australian Children’s Laureate There are a million ways to share a story Nanberry: Black Brother White 978073229022 | BPB | Ages: 12+ • Honour Book, CBC Awards Book of the Year (Older Readers), 2012 Two brothers — one black, one white — and a colony at the end of the world It’s 1789, and as the new colony in Sydney Cove is established, Surgeon John White defies convention and adopts Nanberry, an Aboriginal boy, to raise as his son. Nanberry is clever and uses his unique gifts as an interpreter to bridge the two worlds he lives in. With his white brother, Andrew, he witnesses the struggles of the colonists to keep their precarious grip on a hostile wilderness. And yet he is haunted by the memories of the Cadigal warriors who will one Hitler’s Daughter Pennies for Hitler day come to claim him as one of their own. 9780207198014 | BPB | Ages: 10+ 9780732292096 | BPB | Ages: 10+ This true story follows the brothers as they make • Winner, CBC Awards Book of the Year (Younger Readers), 2001 • Honour Book, CBC Awards Book of the Year • WOW! Award Winner, UK National Literacy Association, 2001 (Younger Readers), 2013 their way in the world — one as a sailor, serving in • Notable Book, US Library Association • Winner, NSW Premier’s History Award the Royal Navy, the other a hero of the Battle of • Koala Awards Roll of Honour, 2007 and 2008 (Young People’s History Prize), 2013 Waterloo. • Semi-Grand Prix Award, Japan • Shortlisted, Queensland Literary Awards (Children’s Book), 2013 The bombs were falling and the smoke rising from It's 1939, and for Georg, son of an English academic No less incredible is the enduring love between the the concentration camps, but all Hitler's daughter living in Germany, life is full of cream cakes and gentleman surgeon and the convict girl who was knew was the world of lessons with Fraulein Gelber loving parents. -

Children's Dyslexic Books New Releases 2019

Junior New Releases Title: Weirdo #1 Author: Anh Do ISBN: 9780369329011 Retail Price: 29.99 AUD Pages: 126 Publication Date: 6/11/2019 Category: JUVENILE FICTION / Humorous Stories BISAC: JUV019000 Format: [Dyslexic Edition] Original Publisher: Scholastic Australia About the Book: My parents could have given me any first name at all, like John, Kevin, Shmevin ... ANYTHING. Instead Iâ €™m stuck with the worst name since Mrs Face called her son Bum. Weir Do’s the new kid in school. With an un- forgettable name, a crazy family and some seriously weird habits, fitting in won’t be easy... But it will be funny! About the Author: Anh Do is a comedian, artist and also one of the highest selling Australian authors of all time, with total book sales approaching 3 million. Junior New Releases Title: WeirdDo #2: Even Weirder Author: Anh Do ISBN: 9780369328793 Retail Price: 29.99 AUD Pages: 126 Publication Date: 29/10/2019 Category: JUVENILE FICTION / Humorous Stories BISAC: JUV019000 Format: [Dyslexic Edition] Original Publisher: Scholastic Australia About the Book: Weir's back and even weirder! But it's not just Weir who's weird, it's his whole family. Not even their pet bird is normal! How will he keep cool with a school trip to the zoo coming up AND Bella's birthday party?! It won't be easy . but it will be funny! About the Author: Anh Do is a comedian, artist and also one of the highest selling Australian authors of all time, with total book sales approaching 3 million. -

Children's Authors, and This the CHARM BRACELET Enchanting Series Will Delight Fans Old and When Jessie Visits Her Grandmother’S House, Blue Moon, New

HarperCollinsPublishers Australia Subsidiary Rights Guide Bologna March 2010 children’s MERCY Rebecca Lim YOUNG ADULT FICTION I don’t know who I am, or how old I am. All I know •Acquired in major pre-empt, this is a stand-out title in a is that when I wake up, I could be any age and crowded genre any one … •Perfect cross-over fiction • Four book series, to be released six-monthly (Mercy A dazzling new series about love, redemption and November 2010, Mercy 2: Evensong May 2011, Mercy celestial connection. 3: Muse November 2011, Mercy 4: End Game May 2012) Mercy ‘wakes’ on a school bus bound for • Strong, sophisticated, witty writing, with a neat twist Paradise, a small town where everyone knows on the angel theme everyone else’s business… or thinks they do. But • Each book stands alone and features a strong Mercy has a secret life. She is an angel, doomed mystery/thriller storyline, but also builds on the to return repeatedly to Earth, taking on a new compelling and mysterious story of Mercy and Luc and ‘persona’ each time she does, in an effort to their relationship resolve a cataclysmic rift between heavenly beings. MERCY Book 1 of the MERCY SERIES The first thrilling book sees Mercy meeting Ryan, ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Rebecca Lim an eighteen-year-old whose sister was kidnapped Rebecca Lim was born in Singapore and grew up in November 2010 two years ago and is presumed dead. When Australia. She studied Law and Commerce at the 9780732291990 another girl is also kidnapped, Mercy knows she University of Melbourne, and had a successful career 210 x 135mm PB has to act quickly and use extraordinary powers as a commercial lawyer before turning to writing. -

Story Time: Australian Children's Literature

Story Time: Australian Children’s Literature The National Library of Australia in association with the National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature 22 August 2019–09 February 2020 Exhibition Checklist Australia’s First Children’s Book Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Parliament Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Charlotte Waring Atkinson (Charlotte Barton) (1797–1867) A Mother’s Offering to Her Children: By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales Sydney: George Evans, Bookseller, 1841 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn777812 Living Knowledge Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Bohrah the Kangaroo 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1453161 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) Dinewan the Emu 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn1458954 Nora Heysen (1911–2003) They Saw It Being Lifted from the Earth 1930 pen, ink and wash Original drawings to illustrate Woggheeguy: Australian Aboriginal Legends, collected and written by Catherine Stow (Pictures) nla.cat-vn2980282 1 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Tommy McRae (illustrator, c.1835–1901) Australian Legendary Tales: Folk-lore of the Noongahburrahs as Told to the Piccaninnies London: David Nutt; Melbourne: Melville, Mullen and Slade, 1896 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn995076 Catherine Stow (K. ‘Katie’ Langloh Parker) (author, 1856–1940) Henrietta Drake-Brockman (selector and editor, 1901–1968) Elizabeth Durack (illustrator, 1915–2000) Australian Legendary Tales Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1953 Ferguson Collection (Australian Printed) nla.cat-vn2167373 Catherine Stow (K. -

Pharaoh the Boy Who Conquered the Nile

www.harpercollins.com.au Pharaoh The Boy Who Conquered the Nile Jackie French Teaching notes prepared by Christine Sarandis ISBN: 9780207200823; ISBN-10: 0207200823; Publication Date: 01/04/2007; Format: B Format Paperback; $15.99 Book Description Prince Narmer is fourteen and, as his father's favourite, destined to be King of Thinis, one of the towns along the River, the only world he knows. But Narmer is betrayed by his brother, and mauled by a crocodile. Now lame and horribly scarred, he is less than perfect and no longer the Golden One. His brother Hawk will be King of Thinis. And rather than remain as Hawk's Vizier, Narmer decides to leave his home and take his chances with the mysterious Trader and the crippled Nitho, whose healing skills have saved his life. Now Narmer must face the desert, and the People of the Sand as well as the challenges in Ur, the largest and most advanced city in the world of 5,000 years ago. Here Narmer learns of farming, irrigation, tamed donkeys and carts with wheels. Most of all, he learns what it means to be a true king and leader. Ages 10-14 1 Jackie French Biography Jackie French is a full-time writer who lives in rural New South Wales. Jackie writes fiction and non-fiction for children and adults, and has columns in the print media. Jackie is regarded as one of Australia's most popular children's authors. Her books for children include: Rain Stones, shortlisted for the Children's Book Council Children's Book of the Year Award for Younger Readers, 1991; Walking the Boundaries, a Notable Book in the CBC Awards, 1994; and Somewhere Around the Corner, an Honour Book in the CBC Awards, 1995. -

Bologna 2020 Rights Guide Children’S & Young Adult Contents

BOLOGNA 2020 RIGHTS GUIDE CHILDREN’S & YOUNG ADULT CONTENTS PICTURE BOOKS JUNIOR & MIDDLE GRADE YOUNG ADULT GENERAL ENQUIRIES If you are interested in any of the titles in this Rights Guide or would like further information, please contact us: Elizabeth O’Donnell International Rights Manager HarperCollins Publishers (ANZ) t: +61 2 9952 5475 e: [email protected] HarperCollins Publishers Australia Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A565, Sydney South NSW 1235 AUSTRALIA PICTURE BOOKS All the birds are excited about the Big Beaky Bird Ball – except LEONARD Leonard. His warble-warble waltz with the magpies is more DOESN’T wobble-wobble, and his caw-caw can-can with the crows is a can’t-can’t. The puffins are prancing, the rosellas are rocking DANCE and you should see the flamingo go-go-go! Everyone is FRANCES WATTS jumping and jiving, but not Leonard. & Leonard doesn’t dance. JUDY WATSON Then an unexpected encounter changes everything ... AGES: 3+ Rights Held: World English and translation Rights licensed: Frances Watts and Judy Watson’s previous A toe-tapping story about picture book collaboration has been licensed in the UK, US, finding your own rhythm Canada and Turkey from the award-winning PICTURE BOOKS creators of Goodnight, Mice! June 2019 | 32pp | 287x210mm | Hardback | ISBN 9780733333040 Rupert isn’t real, but he has a real friend, William. They MY REAL both love sport, painting and music and have amazing FRIEND adventures together in William’s imagination. DAVID HUNT & But why can’t they have the adventures that Rupert wants? And what will happen if William no longer wants an LUCIA MASCIULLO imaginary friend? AGES: 3+ A heartwarming story of friendship, identity and the power of imagination from bestselling author David Hunt It’s not easy being and award-winning illustrator Lucia Masciullo. -

SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus

SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus SUGGESTED TEXTS for the English K–10 Syllabus © 2012 Copyright Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales. This document contains Material prepared by the Board of Studies NSW for and on behalf of the State of New South Wales. The Material is protected by Crown copyright. All rights reserved. No part of the Material may be reproduced in Australia or in any other country by any process, electronic or otherwise, in any material form or transmitted to any other person or stored electronically in any form without the prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW, except as permitted by the Copyright Act 1968. School students in NSW and teachers in schools in NSW may copy reasonable portions of the Material for the purposes of bona fide research or study. Teachers in schools in NSW may make multiple copies, where appropriate, of sections of the HSC papers for classroom use under the provisions of the school’s Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) licence. When you access the Material you agree: to use the Material for information purposes only to reproduce a single copy for personal bona fide study use only and not to reproduce any major extract or the entire Material without the prior permission of the Board of Studies NSW to acknowledge that the Material is provided by the Board of Studies NSW not to make any charge for providing the Material or any part of the Material to another person or in any way make commercial use of the Material without the prior written consent of the Board of Studies NSW and payment of the appropriate copyright fee to include this copyright notice in any copy made not to modify the Material or any part of the Material without the express prior written permission of the Board of Studies NSW. -

Suggested Titles for the Australian Curriculum 2012 Indigenous

Suggested Titles for the Australian Curriculum 2012 Indigenous Themes Coonardoo by Katharine Pritchard , Coonardoo is the moving story of a young Aboriginal woman trained from childhood to be the housekeeper at Wytaliba station and, as such, destined to look after its owner, Hugh Watt. Introduced by Drusilla Modjeska, this frank and daring novel set on the edge of the desert still raises difficult questions about the history of contact between black and white, and its representation in Australian writing. ISBN: 9780207198472 RRP $22.95 Wild Cat Falling by Mudrooroo "Wild Cat Falling" is the story of an Australia Aboriginal youth who grows up on the ragged outskirts of a country town. He falls into petty crime, goes to gaol and comes out to do battle once more with the society that put him there. ISBN: 9780207197321 RRP 22.95 Darby: One hundred years of life in a changing culture By Liam Campbell After assisting the war effort, he returned to his traditional country northwest of Alice Springs where he became a much loved community and ceremonial leader. He gained recognition as a successful artist and strong advocate for Aboriginal law and culture. ISBN: 9780733319259 RRP $35.00 The Tears of Strangers Stan Grant was born in 1963 into the Wiradjuri people - a tribe of warriors who occupied the vast territory of central and southwestern New South Wales. For 100 years the Wiradjuri waged a war against European invasion and settlement. This war has largely been ignored by historians and politicians but will be burnt into the hearts and minds of the Wiradjuri forever. -

Frankfurt 2020 Rights Guide New Releases Fiction & Non-Fiction Contents

FRANKFURT 2020 RIGHTS GUIDE NEW RELEASES FICTION & NON-FICTION CONTENTS FICTION General Fiction Harlequin Fiction NON-FICTION General Non-fiction Harlequin Non-fiction True Crime Cookery & Lifestyle Biography & Autobiography Sport History & Popular Science Health & Wellbeing Parenting SUB-AGENTS GENERAL ENQUIRIES If you are interested in any of the titles in this Rights Guide or would like further information, please contact us: Elizabeth O’Donnell International Rights Manager HarperCollins Publishers (ANZ) t: +61 2 9952 5475 e: [email protected] HarperCollins Publishers Australia Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2000 PO Box A565, Sydney South NSW 1235 AUSTRALIA FICTION TITLES GENERAL FICTION GENERAL FICTION ALL OUR SHIMMERING SKIES SORROW AND BLISS TRENT DALTON MEG MASON The bestselling author of Boy Swallows Universe, A dazzling, distinctive novel full of pathos, fury, wit and Trent Dalton returns with All Our Shimmering tenderness from a boldly talented and original writer. Skies – a glorious novel destined to become another Australian classic. Manuscript available Manuscript available 352pp | 234x153mm Paperback | ISBN 9781460757222 September 2020 | 480pp | 234x153mm Paperback | ISBN 9781460753903 Darwin, 1942, and as Japanese bombs rain down, motherless Molly Hook, the gravedigger’s This novel is about a woman called Martha. She knows there is something wrong with her but she daughter, is looking to the skies and running for her life. Inside a duffel bag she carries a stone heart, doesn’t know what it is. Her husband Patrick thinks she is fine. He says everyone has something, alongside a map to lead her to Longcoat Bob, the deep-country sorcerer who she believes put a the thing is just to keep going. -

1 the Shaggy Gully Times

The Shaggy Gully Times written by Jackie French, illustrated by Bruce Whatley Teaching Notes written by Chris Sarandis Book Description Look! Up in the sky! Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it's a wombat, a sheep and a dancing kangaroo – And they're on the front page of The Shaggy Gully Times! The small bush town of Shaggy Gully is home to many animals, including local celebrities Mothball, Pete and Josephine. Pete the Sheep runs a successful hairdressing salon and Josephine is a renowned ballerina. Mothball is editor of the weekly newspaper, The Shaggy Gully Times. She also can't spell. This week's edition is jam–packed with exciting news of how a small town comes together to rescue some unfortunate animals from Mr Nasty's zoo. How did the rescue take place and will the newcomer animals fit into life in Shaggy Gully? Read all about this and other exciting news in the punniest newspaper ever! Ages 7+ 1 Download The Shaggy Gully activity kit: http://www.harpercollins.com.au/shaggygully and become part of the Shaggy Gully community! Jackie French Jackie French is a full-time writer who lives in the bush in New South Wales. She writes fiction and non-fiction for children and adults, spent many years on tv on Burke ’s backyard and still does radio segments and and has columns in the print media. Jackie is one of the few authors to win Literary Awards and Children’s Choice awards. In 2007 alone she won the WA children’s choice award for They Came on Viking Ships, which has also just been shortlisted for an award in the UK; Diary of a Wombat was voted as the favourite book of 2007 by the children of the northern territory; Josephine wants to Dance won the Abia Award and Monkey Baa’s production of jackie Hitler’s Daughter won a Helpman Award and the driver’s Award for the Best Touringf Production.